Lily Clark channels the sublime beauty of water in sculptural fountains

Wallpaper* Future Icons: LA-based Lily Clark is influenced by physics, Light & Space artists, and the California landscape

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Throughout history, humans have tried to tame water through aqueducts, dams, channels, and levees. But no matter how sophisticated the engineering, the unruly substance almost inevitably goes where it wishes. Perhaps this tension is why Los Angeles-based artist Lily Clark’s work is so captivating: She’s able to masterfully capture the sublime beauty of water in meditative and architectural fountains, sinks, and installations. 'I’m always learning from water and am humbled by it because it’s such a challenging medium to get a hold of,' Clark says. 'Water always misbehaves.'

Lily Clark: designing with water

Loop fountain

Clark, who trained as a graphic designer at the Maryland Institute College of Art, started working with water about six years ago while she was living in New York City. At the time, she became preoccupied by fluid dynamics after seeing an exhibition by the artist Tauba Auerbach that referenced the scientific discipline. At the same time, she was thinking about the atmosphere, landscape, and geology of Los Angeles, where she grew up. She blended these influences in table top fountains that quickly grabbed the attention of magazine editors. When she returned to L.A. in TK, she steadily began to shift the majority of her work to water features.

Lily Clark in her LA studio

There is a deeply Californian sensibility to Clark’s sculptures. The narrow sluices in her Comb fountain are scaled-down versions of the 440-foot-tall spillways on the Pine Flat Dam, while its minimalist white forms reference Rudolph Schindler’s homes around Silver Lake, a reservoir in her childhood neighbourhood. Loop — a fountain with curved shapes borrowed from streamlined Art Deco design and a vessel for ikebana arrangements — continually cycles water between its two tiers and is a metaphor for the large-scale infrastructure that moves water from the Sierra Nevada mountains to coastal cities.

Despite Clark’s heavy-duty references, the overall effect of her sculpture is subtle and nods to Light and Space artists of the 1960s who explored perception. Just as Helen Pashgian contained the ephemeral properties of light in her prismatic cast-resin spheres, Clark’s sculptures are vessels for the physicality of water: how reflections glimmer on its surface, how its characteristics shift depending on the material it flows across, and how it has the strength to erode stone.

Fountain for Stroll Garden, for Design Miami 2022

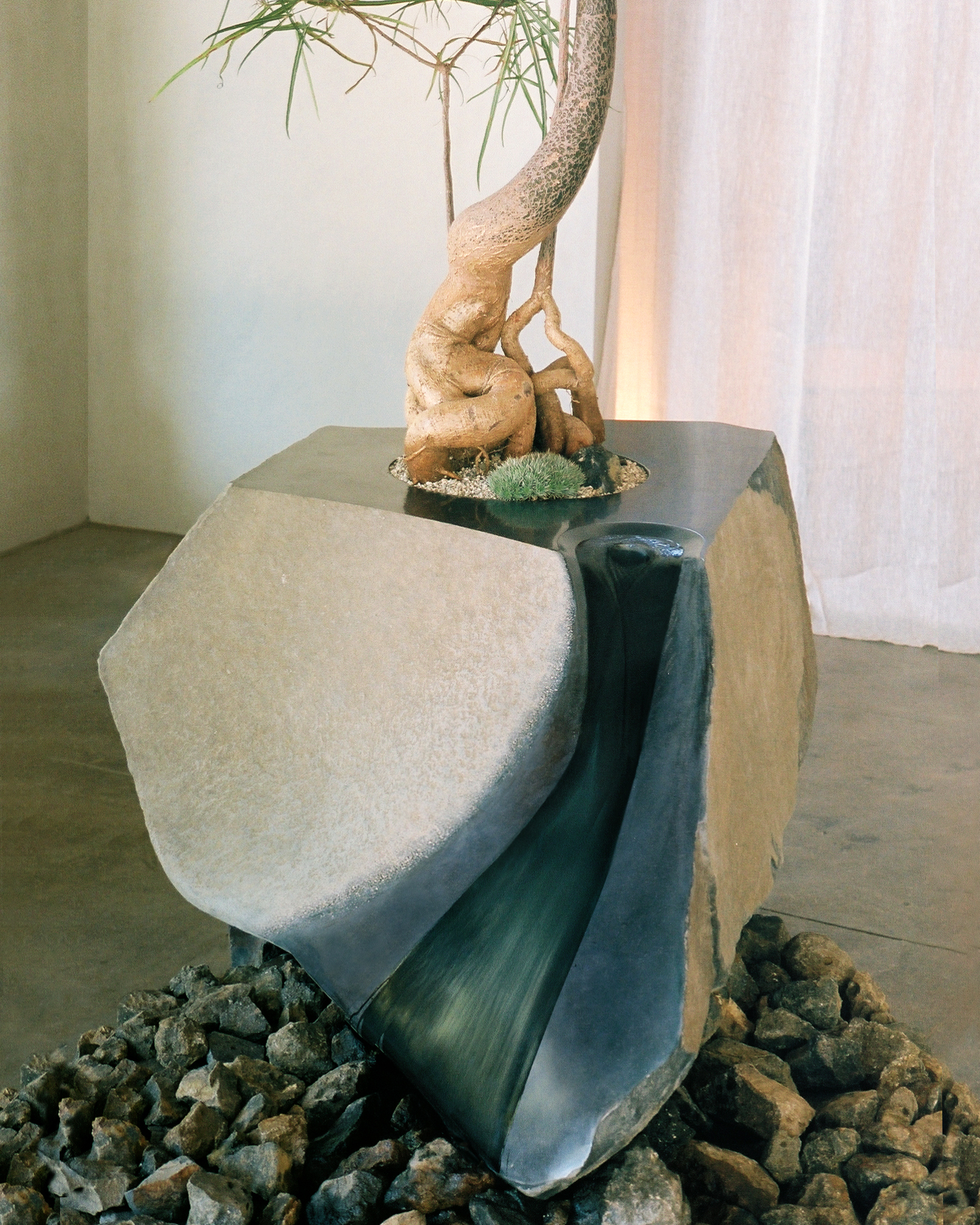

Lately, Clark has been experimenting with how different materials can help her choreograph water in new ways. Her stone sculpture for the TikTok-viral photographer David Suh’s studio is reminiscent of Isamu Noguchi’s Water Stone; both are cleaved from basalt, with rough-hewn and polished surfaces and a thin veil of water that glistens down the side.

Bespoke stone and steel water feature

In a commission for Piaule, a boutique hotel in the Catskill mountains, she collaborated with the artist Lachlan Turzcan on a site-specific installation with a steel vessel that captures rainwater and tips over once it’s full. Now, she’s developing a stone-and-resin composite that will be extremely hydrophobic (meaning it repels water) in order to achieve laminar flow, a phenomenon in which moving water appears still, like an optical illusion. '

In the past, I was really interested in controlling water in an infrastructural, linear way,' Clark says. 'I'm a little more interested now in finding an organic middle zone between the way water wants to move and the way it can be manipulated.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Bluestone Basin for Piaule

Dasu Fountain

Diana Budds is an independent design journalist based in New York