How Isamu Noguchi dissolved the boundaries between art, design and the city

Isamu Noguchi shaped cities, interiors and everyday rituals through design: here’s everything you need to know about the interdisciplinary American modernist who believed art belonged in public life

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

One of the most influential figures of 20th-century modern design, Isamu Noguchi (17 November 1904 – 30 December 1988) was an American artist, furniture designer, landscape architect and sculptor whose work indelibly shaped the visual language of the modern world. It was maybe his diverse heritage – his father was a Japanese poet, his mother an American writer – that informed much of his paradigm-defying work. Over a six-decade career, spanning studios in New York and Japan, Noguchi produced work ranging from poetic gardens to furniture, lighting, ceramics, architecture, landscapes and even set designs.

Less known, yet deeply formative, was Noguchi’s extraordinary decision during the Second World War to voluntarily enter the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona in 1942 (where as many as 17,000 Japanese-Americans were interned during the war; residents of New York, such as Noguchi, were officially exempt). Intended as both a protest and an attempt to contribute meaningfully to a forcibly displaced community, the gesture was met with resistance, and his ambitions to improve conditions in the camp were ultimately thwarted. After seven months, he left the camp with a resolve to be, above all else, an artist.

Furniture and iconic associations

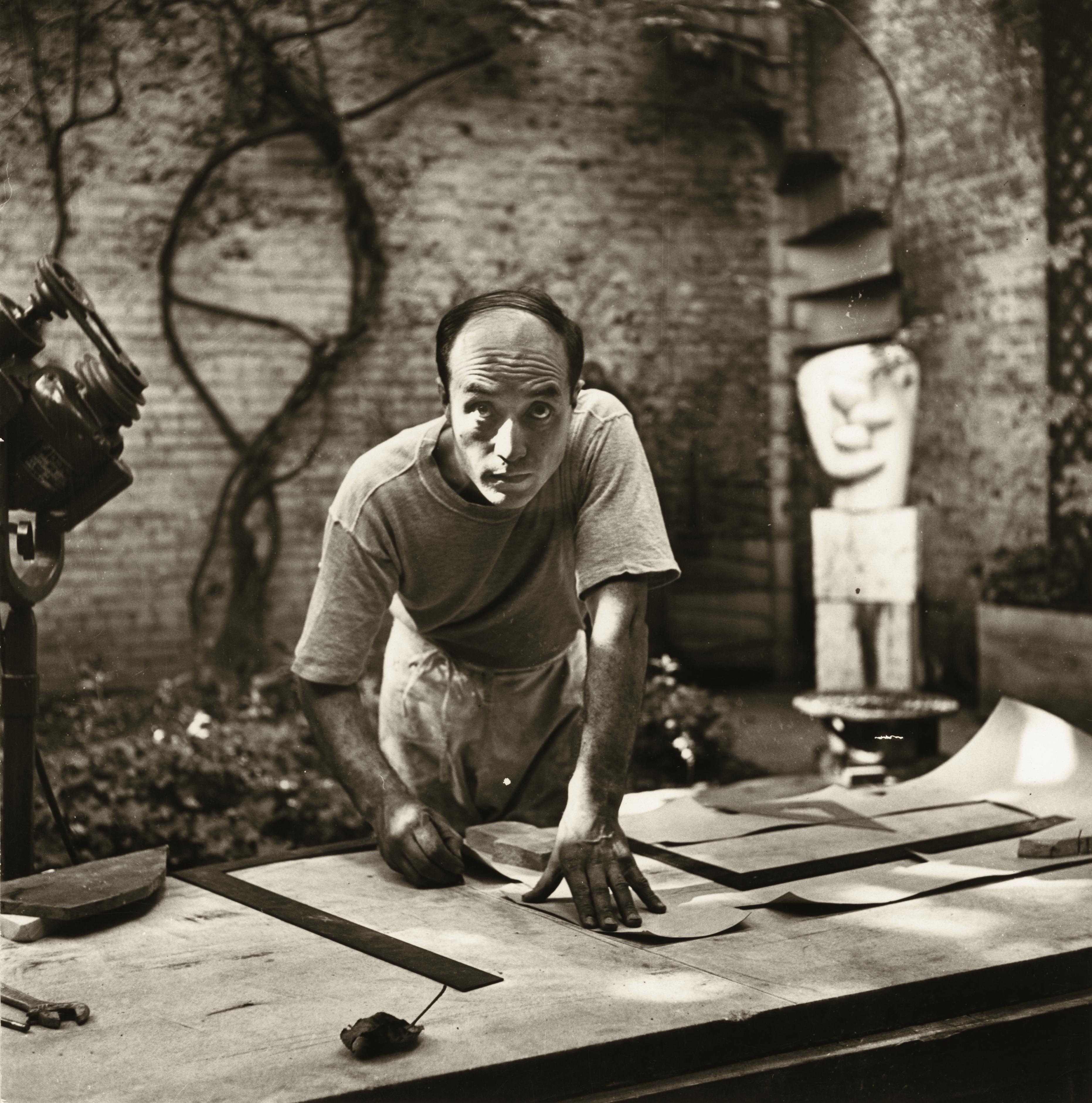

Isamu Noguchi photographed in 1946

After returning to New York, Noguchi’s work throughout the 1940s became deeply entwined with Surrealism, with experimental mixed-media constructions, landscape reliefs and biomorphic sculptures composed of interlocking planes.

A pivotal moment came in 1947, when he began collaborating with Herman Miller, an association that produced some of modernism’s most enduring designs, including the celebrated ‘Noguchi’ table, still in production today. Parallel partnerships with Knoll further expanded his furniture and lighting repertoire, leading to classics such as the ‘Cyclone’ tables and the three-legged ‘Cylinder’ lamp.

Among his other sculptural furniture pieces is the ‘Freeform’ sofa, whose fluid, organic silhouette stood apart from the rectilinear designs of its era. Equally impressive is the ‘Akari’ light series, which treats illumination as something atmospheric and weightless; each lamp handcrafted in Gifu, Japan, and conceived to ‘float’ as much as glow.

Sets, sculptures and scapes

Isamu Noguchi with Kouros (1945) at the exhibition ‘Fourteen Americans’, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 10 September 1946 – 8 December 1946

Incidentally, Noguchi’s affinity for design revealed itself well before his forays into furniture. As early as 1935, he was creating stage sets for dance pioneer Martha Graham, initiating a lifelong collaboration that would extend to figures such as Merce Cunningham, Erick Hawkins and George Balanchine.

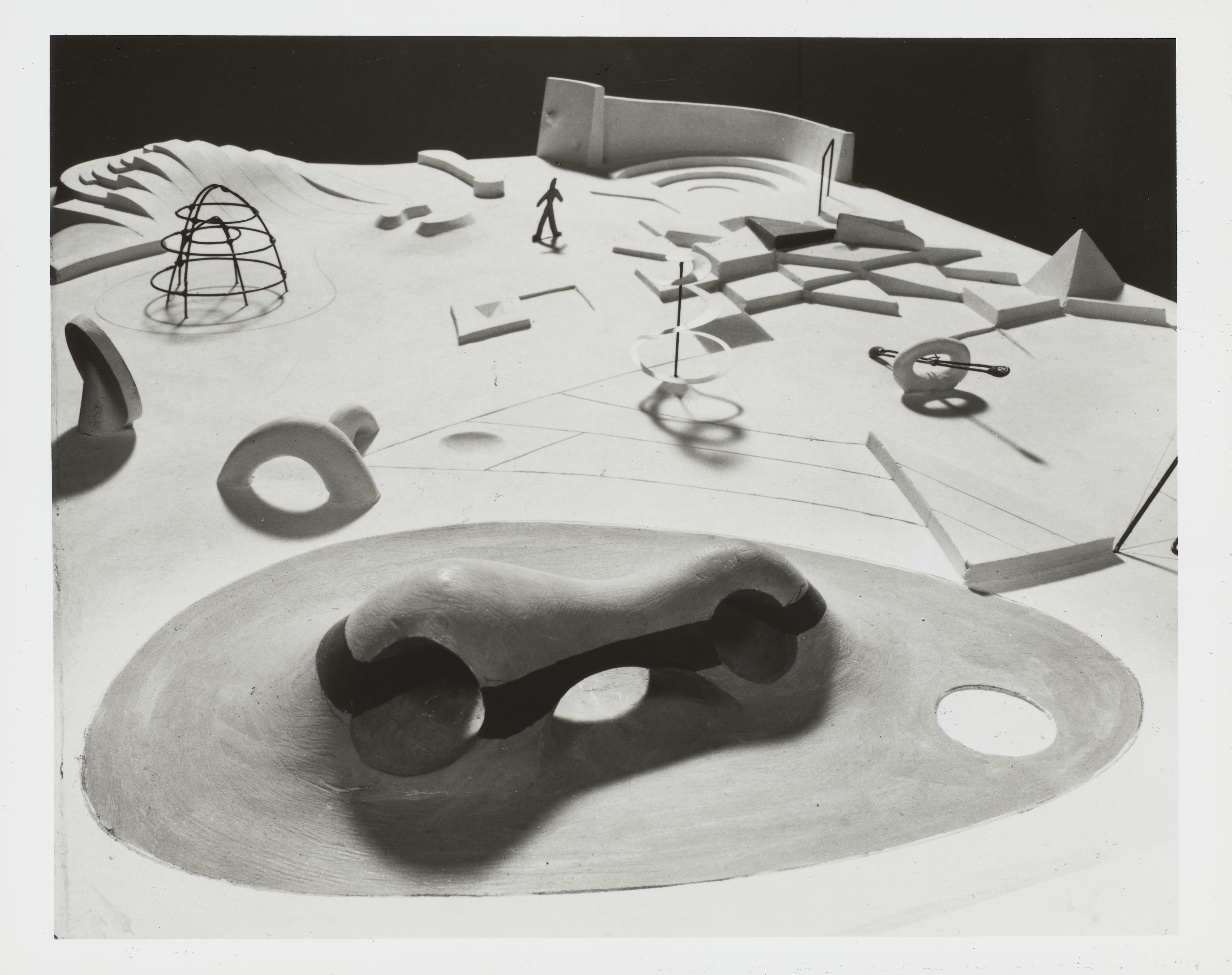

His practice also unfolded alongside some of the era’s most consequential architects. Among them was Louis Kahn, with whom Noguchi collaborated on the unrealised Adele Levy Memorial Playground in New York City’s Riverside Park during the 1960s. And, when the construction of the United Nations building erased a nearby play space, the women of Beekman Place appealed to him for a replacement. His proposal was warmly embraced, and while never realised, its model was ultimately exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Model for UN Playground, 1952

His first realised public commission arrived early – the Associated Press Building Plaque in New York was initiated in 1938 and unveiled in 1940. Fabricated at General Alloys in Boston, the work transformed a modest plaster model into nine monumental sections of stainless steel, together weighing nine tons.

In the late 1950s, his vision for public space took on a more contemplative register when Unesco commissioned the Garden of Peace in Paris, a Japanese-style garden gifted by Japan, composed of stones shipped from its landscapes, water and carefully chosen plantings, conceived as a living symbol of cultural dialogue and reconciliation.

Red Cube, 1968

Sunken Garden for Chase Plaza, 1961-64

This belief in sculpture as civic experience reached a dramatic urban scale in 1961, when Noguchi began collaborating with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill on the plaza of the Chase Manhattan Bank building on Liberty Street, embedding a circular sunken garden beneath the surface of the block-long forecourt. Soon after came Red Cube (1968), the tilted steel monolith that still anchors Lower Manhattan, its vivid geometry offering a quiet, corrective harmony amid the city’s vertiginous canyons.

Gardens of The Noguchi Museum, New York

In 1985, Noguchi brought his lifelong commitment to public art to a culmination with the opening of The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum in Long Island City, New York. Designed and founded by the artist himself (and now known simply as The Noguchi Museum), it stands as both archive and landscape, housing realised and unrealised works alike.

The museum's director, Amy Hau, says, 'The space exists at a rare crossroads of sculpture, design, architecture and landscape and that hybridity is at the heart of everything we do. Noguchi himself moved fluidly across disciplines, never seeing boundaries as fixed. That legacy shapes our curatorial and programming choices today, encouraging us to think expansively, to collaborate across fields and to present work that speaks simultaneously to material, space, movement and human experience.'

Noguchi in New York: see the master's work

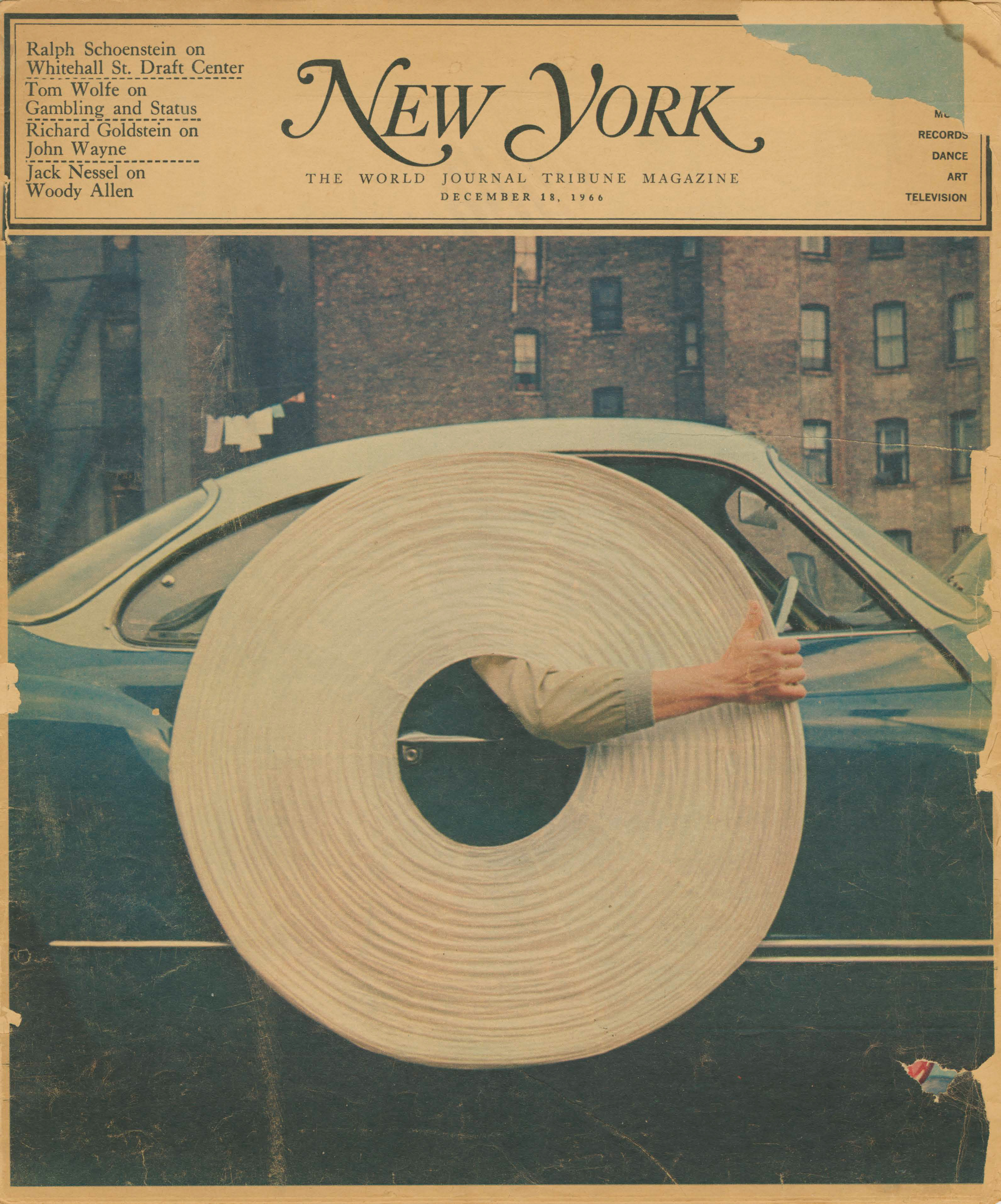

A photograph of Noguchi carrying a folded ‘Akari’ lamp, on the cover of New York magazine (18 December 1966, when the title was a supplement of the New York Herald Tribune)

From 4 February – 13 September 2026, The Noguchi Museum will present ‘Noguchi’s New York’, a landmark exhibition illuminating Isamu Noguchi’s lifelong and deeply imaginative relationship with New York City, timed to coincide with the 75th anniversary of his ‘Akari’ light sculptures. Curated by Kate Wiener, the exhibition traces how the city shaped Noguchi’s thinking and work.

‘He truly was restless in his desire to “make New York a little bit [of a] better place”’

Curator Kate Wiener

A model of Isamu Noguchi's Riverside Park playscape

Wiener reflects: 'I was surprised by the sheer number of projects that Noguchi considered for New York, from an environmental playscape in Riverside Park, to the design of a sculpture garden for The Museum of Modern Art. While he was able to realise ten in total, most of these never came to be, and tragically, many that were constructed have since been destroyed. Even now, years into my research, I’m discovering new proposals: just this week, I was reading correspondence in our archive and learned of an idea he had for a sculpture garden along the central strip of Park Avenue. He truly was restless in his desire to “make New York a little bit [of a] better place.”’

Associated Press Building Plaque, 1938-40

The exhibition brings together seminal works, including Red Cube, Sunken Garden and the Associated Press Building Plaque, alongside rare archival material that reveals lesser-known ambitions. These articulate Noguchi’s expansive artistic philosophy, one rooted in openness, experimentation and the transformative power of play.

Aditi Sharma is a content specialist with 14 years of experience in the design and lifestyle space. She specialises in producing content that resonates with diverse audiences, bridging global trends with local stories, and translating complex ideas into engaging, accessible narratives.