For Isamu Noguchi, New York City was the ultimate playground

A new show, now on view at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, explores the artist's relationship with the city he called home

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The artist who’s left their hometown and gone elsewhere is a familiar exhibition trope in New York right now. There’s ‘Monet and Venice’, currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum, while the Met recently wrapped up the blockbuster ‘Sargent and Paris’.

It would be easy to do the same with Isamu Noguchi in Paris, Japan, and Arizona, to name a few places where the artist lived and worked. A new show at the Noguchi Museum in Queens explores his relationship with New York, the city he called his hometown for much of six decades.

Noguchi in front of the Plaza Hotel at the debut of his first public sculpture on New York City land, Unidentified Object (1979) in Doris C Freedman Plaza, Central Park, 1979

‘I’m really a New Yorker,’ Noguchi once said, ‘Not Japanese, not a citizen of the world, just a New Yorker who goes wandering around like many New Yorkers.’

The possessive tone of the exhibition title, ‘Noguchi’s New York’ is well-warranted in this fantastic survey, which dedicates a substantial amount of space to the artist’s projects in the city, about 30 in total. Treasures, such as plans, models and photos, are the stuff of dreams and what-ifs. The exhibition also includes delightful tidbits about Noguchi's creative life in the Big Apple, such as the Phaedra stage set for Martha Graham or his friendship with Yoko Ono. It was all in service, as curator Kate Wiener said, of Noguchi’s ‘decades-long effort to try and shape the city into a more beautiful, natural space for connection and reflection’.

Noguchi at his MacDougal Alley Studio, 25 September 1946, New York

A simple timeline can’t quite capture Noguchi’s relationship with New York, given his frequent comings and goings. Noguchi, who was born in 1904, and first arrived in New York as a pre-medical student at Columbia University in 1922, soon turned to art instead. He then kept coming back, between relocations that were glamorous – in Paris, Hollywood, Mexico City, China, Japan and elsewhere – and one that very much was not: the Poston, Arizona Japanese-American internment camp during the Second World War. Some of these experiences are not especially relatable to the average New Yorker, say, studying under Constantin Brâncuși or meeting Buckminster Fuller in Greenwich Village. Others, such as being priced out of Manhattan and moving to Astoria, Queens, very much are.

The exhibit offers a series of snapshots of Noguchi’s many engagements with the city. There is a row of his early busts, a testament, Wiener explained, to the 'extraordinary networks of people that he met while he was in New York'. There’s dancer Michio Ito rendered in a bronze mask; Clare Booth Luce in marble; and a craggy ceramic Gabriel Orozco. Buckminster Fuller’s noggin appears in chrome-plated bronze, a nod, seemingly, to his suggestion that Noguchi paint his studio entirely in silver.

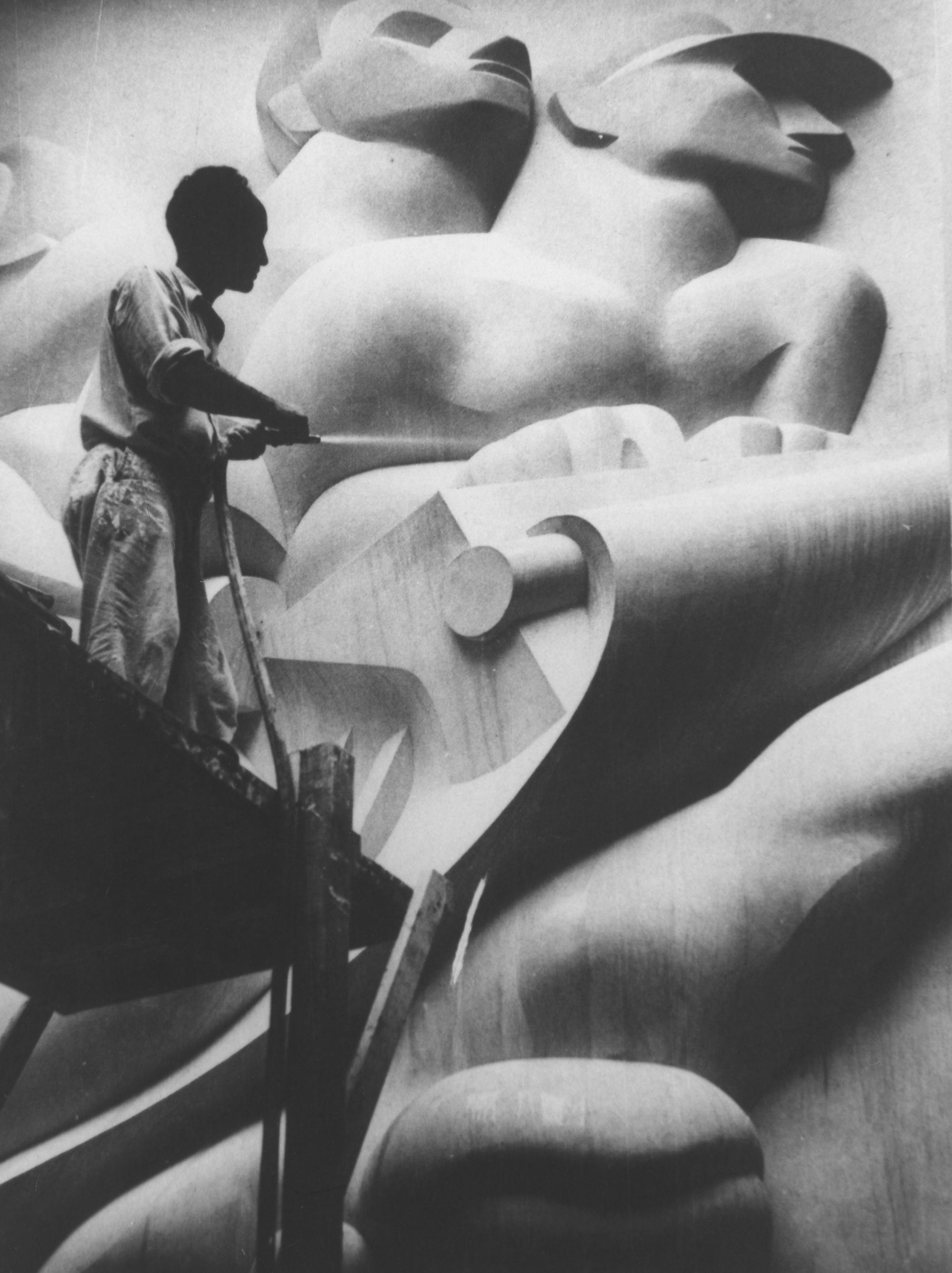

Noguchi working on News, a monumental sculpture above the entrance to 50 Rockefeller Plaza, in 1939

A considerable amount of real estate at the exhibit is occupied by enchanting models and diagrams of not one but multiple playgrounds that Noguchi laboured to build in New York. Play Mountain, for example, was a 1933 proposal for a block-large park featuring slopes, terraces, a pool and a bandshell. The project, however charming, proved Sisyphean for Noguchi, as stodgy officials were roundly appalled. Prime among these antagonists was Robert Moses, who as the exhibit text notes ‘laughed the artist out of his office’.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Noguchi tried again and again, with proposals for brilliant Constructivist-spirited playground equipment, including Contoured Playground, a 1941 design that consisted of injury-proof gentle gradations, and a scheme for a 1952 playground on the United Nations campus (Moses also stymied this project, threatening not to build railings around the playground’s border if built).

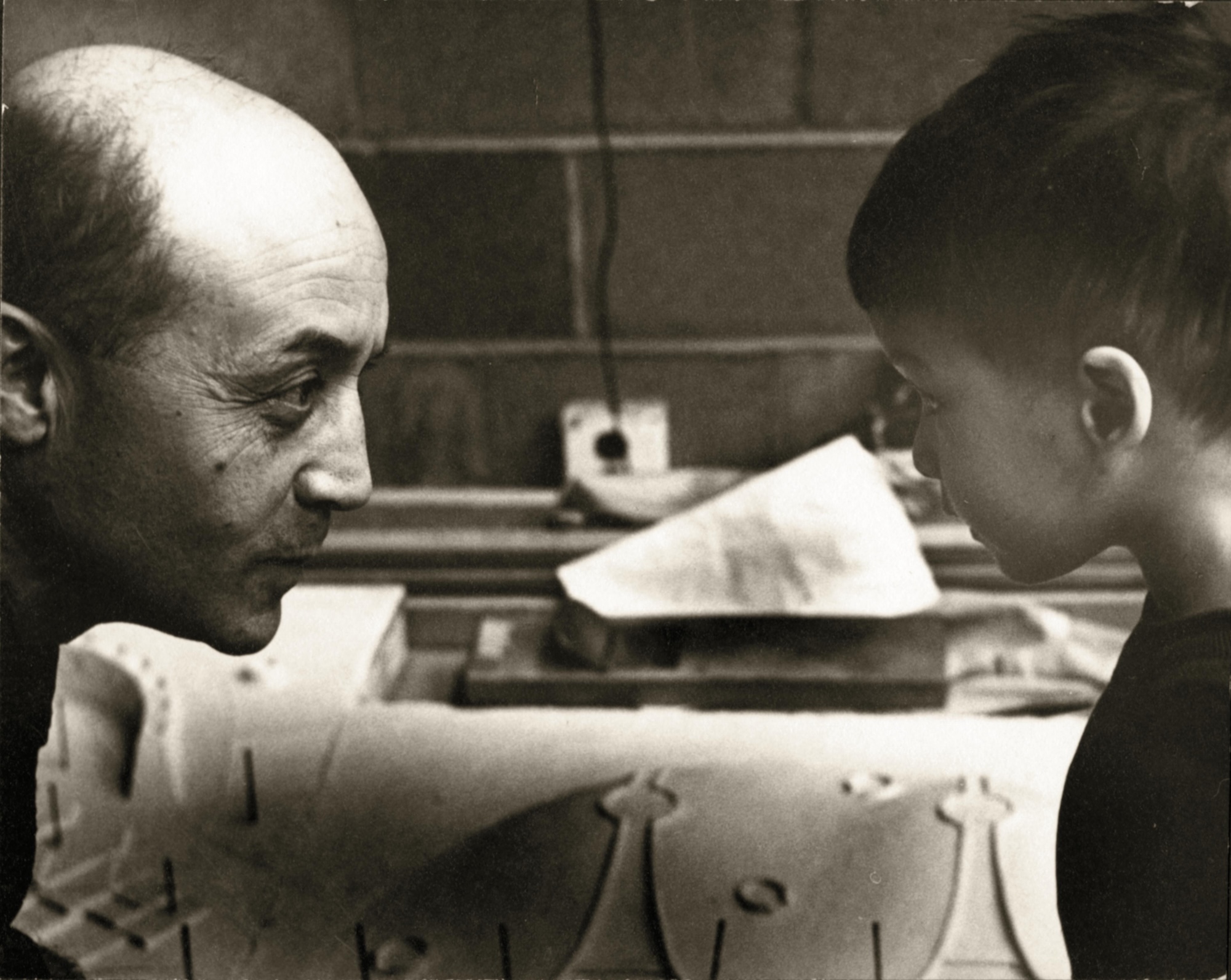

Noguchi and a child with Riverside Park Playground model in 1961

The most dazzling of the playground was an early 1960s project for Riverside Park Noguchi laboured on for five years with fellow modernist Louis Kahn. The plaster and plywood models, which reflect successive fruitless modifications, draw upon Japanese Gardens, Native American serpent mounds, Mayan Pyramids, Indian astronomical observatories, Brâncuși’s Table of Silence and more. Bureaucracy once again intervened; the project was cancelled by New York Mayor John Lindsay. Noguchi and Kahn went on to collaborate elsewhere, but New York missed out.

Isamu Noguchi, Play Mountain, 1933 (cast 1977)

There are tantalising glimpses of other unrealised projects, some newly unearthed, such as talk of Noguchi filling out the early MoMA sculpture garden and building a primate playground at the Bronx Zoo. A letter from the zoo’s president to Noguchi notes of chimpanzees: ‘They are agile and quick and full of mischief. These, too, would also enjoy different floor levels and would probably use a movable swing but not to the same extent that the orangutan would.’ Unfortunately, there’s no evidence of what Noguchi might have come up with for the chimps, but it’s fuel for imagination.

Amid the joyful works are the ghosts of Noguchi projects that succumbed to the wrecking ball. A nightclub in the basement of a former Baptist church. His Time-Life building interior. The 666 5th Avenue waterfall lobby installation (which, fortunately, the museum has in its holdings).

Another destroyed work is the 1975 sculpture Shinto, which was created for the Bank of Tokyo Building. It was dismembered just five years later without a word to the artist. The exhibit features a letter of remarkably poetic resignation from Noguchi: 'The natural mediocrity of the people who worked there must have finally prevailed. We are out on the street where we belong.’

Isamu Noguchi, Red Cube, 1968

All of these works – whether they still stand today or were lost – are testaments to Noguchi’s ‘restless idealism', Weiner explained. He made far more money from private commissions. Noguchi wrote in A Sculptor’s World, ‘I am grateful for the opportunity to do significant public works, and look upon them as challenges to sculpture rather than as jobs.’

Hitch the subway to Manhattan and you can easily view two. Red Cube is a kinetic jolt of steel and man-made colour on Broadway; Sunken Garden consists of river-hewn stones from Kyoto set atop patterned Japanese-and-Chinese influenced paving. The latter project sounds like the very picture of zen, but Noguchi described it ‘like looking onto a turbulent seascape from which immobile rocks take off for outer space’.

A view of Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, 1960-64

Most fascinating of all just might be surprising biographical snippets of Noguchi’s colourful life. There’s a chess table he designed for a 1944 exhibition among august company, such as Robert Motherwell, Yves Tanguy and Dorothea Tanning. There’s a sobering firearm-like granite piece, Sharpshooter, that he created for a MoMA event benefitting the Southern Christian Leadership Council after Martin Luther King was assassinated. Noguchi was even a character witness at a 1976 immigration hearing for John Lennon.

Noguchi best summed up his approach: ‘My way was not the way of words, but the way of doing things, making something which might sort of approach that which one felt the world could be. Little spots here and there, so that instead of going to the moon, you bring the moon to you.’

‘Noguchi’s New York’ is at the Noguchi Museum until 13 September 2026.

Also read our guide to Isamu Noguchi’s life and work