How Massimo and Lella Vignelli brought order to modern design

Ahead of a major retrospective at Triennale Milano, we revisit the work of Massimo and Lella Vignelli – a creative partnership that reshaped modern graphic and product culture

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The story of Massimo Vignelli and Lella Vignelli is, at its heart, a love story, but also a professional union that reshaped international design culture for more than half a century. Two ambitious Italian-born architects met at an architects' convention in 1951, married in 1957, and went on to leave an indelible mark on everything from corporate identity and furniture to the wayfinding systems of modern cities.

Although both were educated in Italy, it was New York – where they settled permanently in 1965 – that became their principal laboratory. From the New York City subway map and signage system to Bloomingdale’s now-iconic shopping bags, Knoll furniture, and the quietly radical interior of St Peter’s Church on Lexington Avenue, the Vignellis’ work embedded itself so deeply into everyday life that it often became invisible. Which, in many ways, was the point.

Ahead of the major retrospective, ‘Lella e Massimo Vignelli’, opening at Triennale Milano on 25 March 2026, we look back over a body of work that consistently resisted fashion, distrusted trendiness, and pursued clarity with near-moral conviction.

Made in Italy: formation and early practice

The Vignellis’ story unfolds between Milan and New York. Both born into families of architects – Massimo Vignelli in 1931 in Milan, and Lella Vignelli (born Elena Valle) in 1934 in Udine – it seemed almost inevitable that they would follow a similar path. At the time, there were no dedicated schools of design; instead, architects, Massimo later recalled, were expected to design everything from ‘the spoon to the city’.

While Massimo studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano and later at the Università IUAV di Venezia, Lella trained as an architect at IUAV before completing a fellowship at MIT. Milan in the postwar decades – animated by cultural revival and industrial optimism – formed the backdrop to their early thinking.

As a teenager, Massimo worked briefly as a draftsman in the studio of the Castiglioni brothers, before undertaking part-time work at the Murano glassworks of his close friend Paolo Venini while still a student, producing early glass designs that marked the beginning of his sustained engagement with industrial production.

Coming to America: design at scale

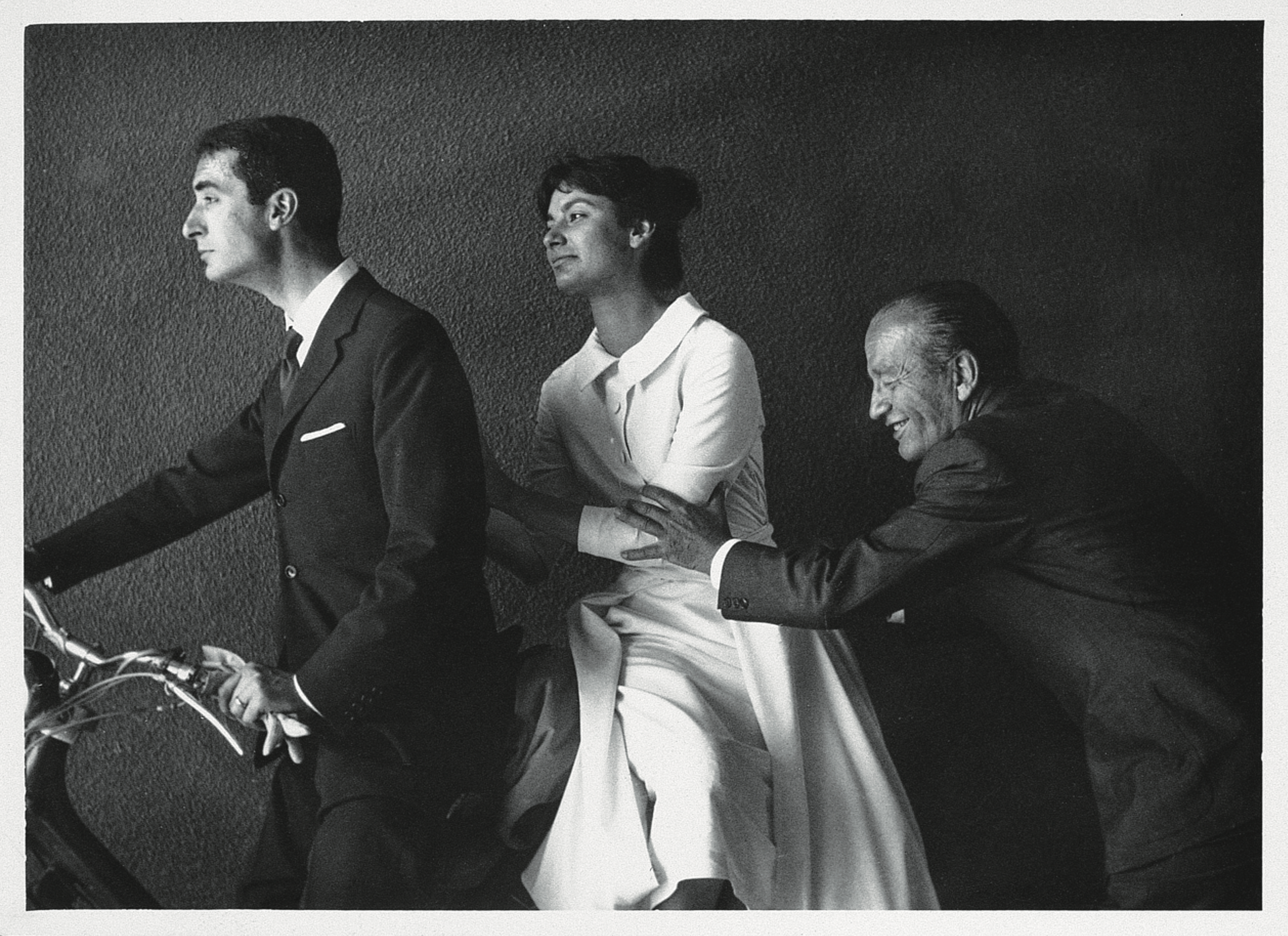

Massimo and Lella Vignelli on their wedding day, 15 September 1957, with Paolo Venini

Shortly after their marriage in 1957, the Vignellis moved to the United States for three years – one spent in Boston, where Massimo undertook a fellowship with Towle Silversmiths in Newburyport, Massachusetts, designing cutlery and domestic objects, and two in Chicago, where he taught at the Institute of Design and worked as a designer at Container Corporation of America.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The couple returned to Milan in 1960, opening an office for design and architecture, with Massimo teaching graphic design in Milan and Venice. Just five years later, they returned to the US once more, this time settling in New York, where Massimo was appointed to lead the local office of Unimark International, the design consultancy he had co-founded with, among others, Dutch graphic designer Bob Noorda.

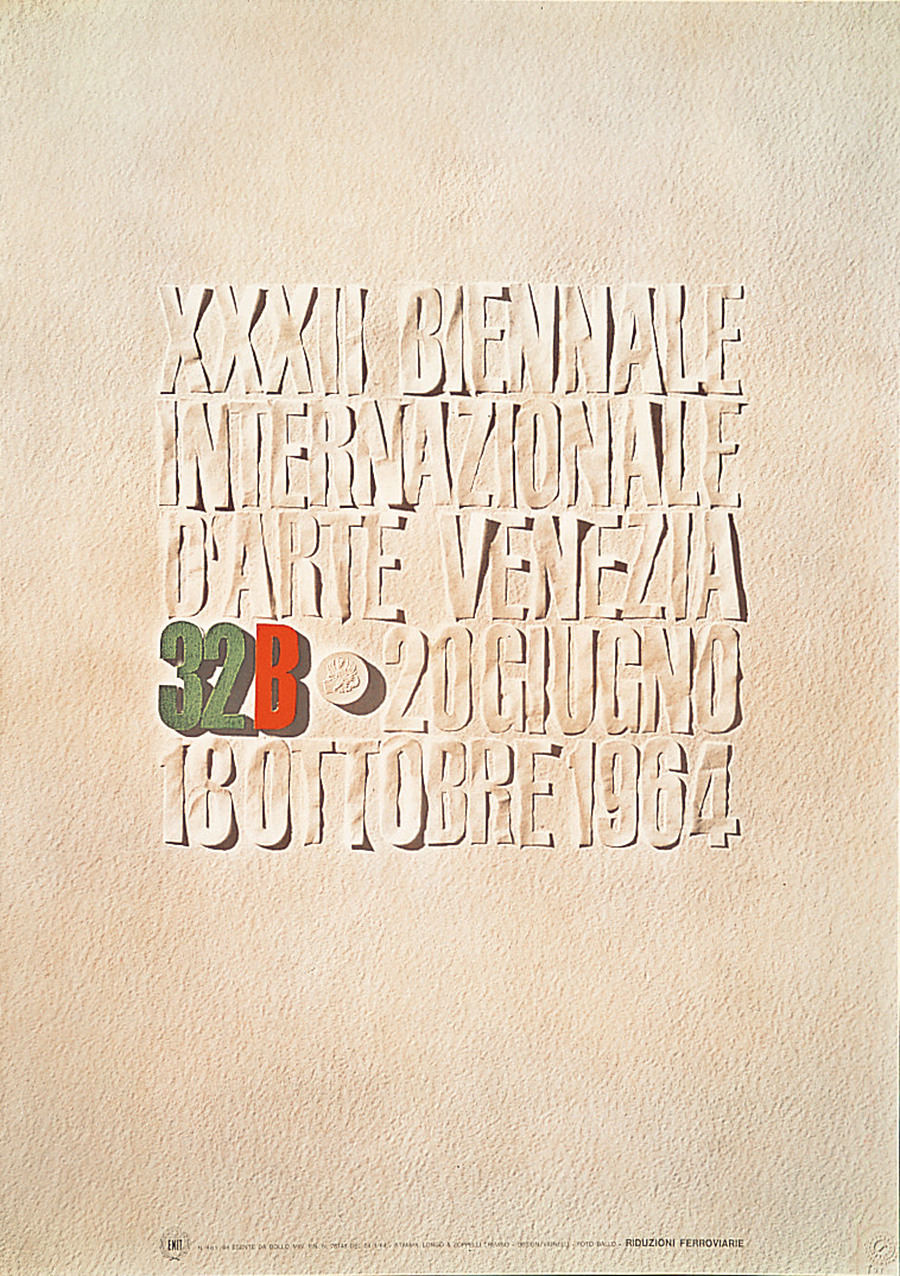

The Vignellis hand-cut the letters from a sheet of paper to create this poster for the International Biennale of Art in Venice in 1964

From this point, New York became their permanent base. Their work increasingly focused on large-scale graphic systems, corporate identity and public commissions – areas in which clarity, consistency and organisation were central concerns – reflecting Massimo’s oft-stated belief that 'if you can design one thing, you can design everything'.

Instinct over consensus

Upon its debut in 1964, the Vignellis’ tableware won the prestigious Compasso d’Oro. Designed to be stacked in a tall, straight column that maximises storage space and creates a neat cabinet interior, each piece fits securely into the other because of a small lip on the bottom. This lip also lifts the piece off the tabletop, giving it the appearance of hovering.

During a talk at Design Indaba in 2007, Massimo Vignelli spoke about the importance of finding what he called 'good clients' – not those seeking novelty, but those willing to take risks and trust judgement. It was a lesson learned early. While in the US on his fellowship in the late 1950s, Massimo designed a set of glass and silverware vessel prototypes that were rejected as unsuitable for the American market. Undeterred, he took the designs back to Europe, where they were picked up by Venini and Christofle and produced for decades (and remain popular on vintage sites). The experience cemented a lifelong distrust of market research and a belief in instinct over consensus.

The American Airlines logo of 1967 – unchanged for nearly half a century – was conceived as a clear, durable branding system

This approach underpinned many of the Vignellis’ most influential commissions. At Unimark International, and later through Vignelli Associates (founded in New York in 1971), they developed corporate identities defined by restraint and internal logic. The American Airlines logo of 1967 – unchanged for nearly half a century – was conceived as a clear, durable branding system. 'How can you improve it?' Massimo later asked.

Systems over style

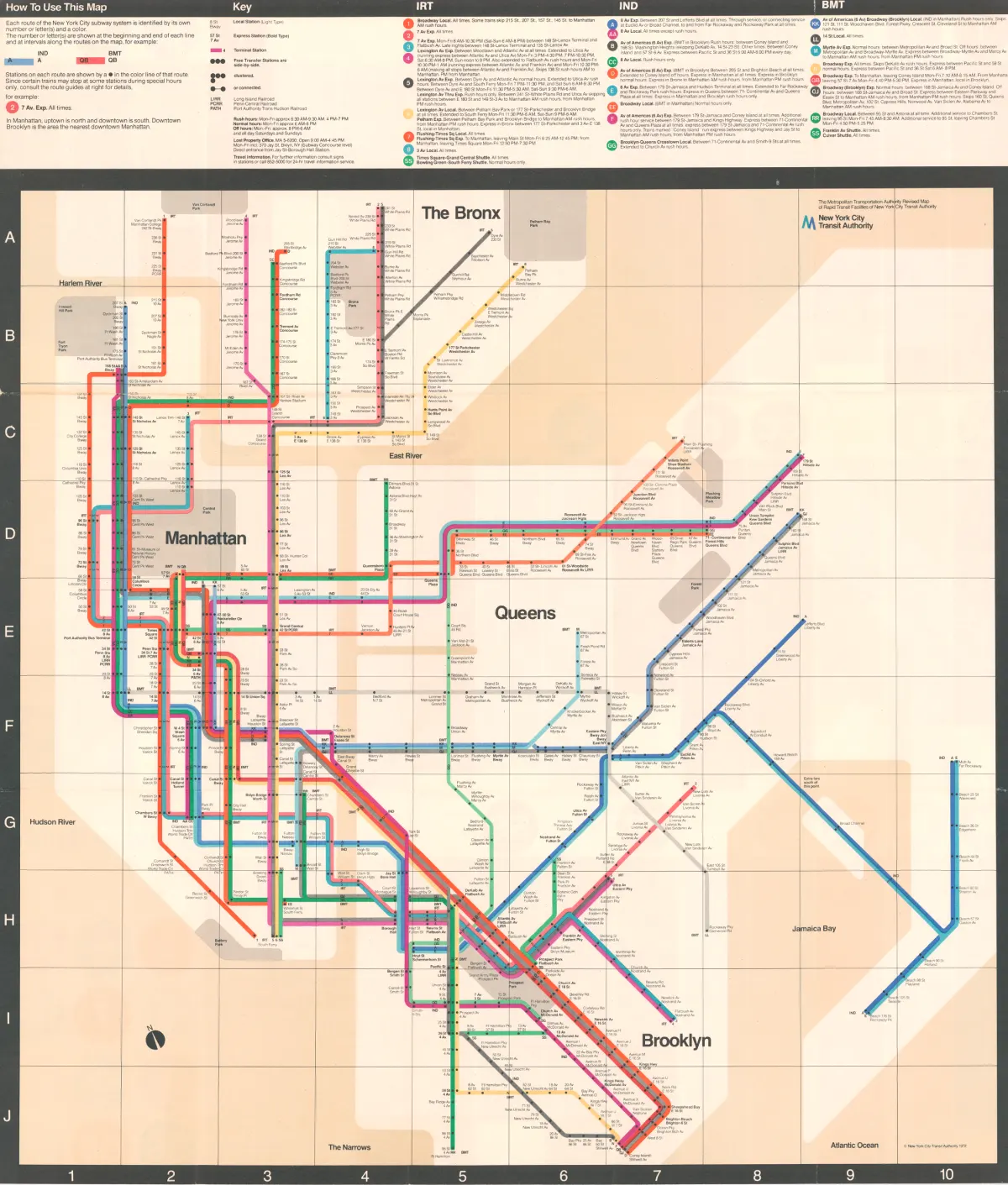

The Vignellis’ New York City subway map, designed in 1970, set a benchmark for thinking about navigation as a design problem rather than a purely cartographic one

Perhaps nowhere was this thinking more visible than in the Vignellis’ work for the New York City subway signage and map introduced 1970. Rather than treating signage and mapping as isolated graphics, they approached the transit system as a total information environment. Stations were assigned colours and dots; typography was standardised. The diagrammatic map – later criticised for its abstracted geography – nevertheless set a benchmark for thinking about navigation as a design problem rather than a purely cartographic one.

This commitment to systems extended across disciplines. For Knoll, the Vignellis developed not only furniture but a complete graphic and spatial language. For Bloomingdale's, they rejected a conventional logo entirely, opting instead for bold typographic treatments on brightly coloured bags and boxes – a brand treatment that became instantly recognisable,

Against trend, against obsolescence

The distinctive Bloomingdales logotype designed in 1972

The Vignellis decried ‘trends’ and abhorred designed obsolescence, which Massimo famously described as 'a social crime'. They viewed design as a long-term responsibility, arguing that objects and systems should endure both physically and intellectually. This position put them firmly at odds with postmodernism, which Massimo dismissed as a culture of metaphor and surface play.

Instead, they returned repeatedly to geometry – the cube, the sphere, the pyramid – and to a limited palette of materials and typefaces. 'I see graphic design as the organisation of information that is semantically correct, syntactically consistent, and pragmatically understandable,' Massimo once wrote. 'I like it to be visually powerful, intellectually elegant, and above all timeless.'

This ethos shaped a new generation of designers who were either taught by Vignelli or passed through the studio, most notably Michael Bierut, who worked with the Vignellis for a decade. Writing in Massimo’s obituary for Design Observer, Bierut reflected: 'I learned how to be a designer from Massimo Vignelli.'

Designed by Lella

Made from pressed glass, the Heller ovenware series features ribbed glass and wide rims that double as handles. Although they received a joint credit when it was launched in 1970, in the book Designed by: Lella Vignelli, Massimo credits the range's clever features to his wife, writing 'Lella’s knowledge of cooking was critical in deciding which products to be designed and how they should develop.'

For decades, like in many male-female design partnerships of the 20th century, Lella Vignelli’s role was too often framed as collaborative rather than authoritative. In reality, it was both. At Vignelli Associates, she served first as executive vice president and later as chief executive officer, overseeing operations while maintaining an active design practice. In 1978, the couple founded Vignelli Designs, a company dedicated to product and furniture design, with Lella as president.

Massimo was regarded as the extrovert, while Lella, quieter, more poised, was the level-headed one. In an interview with Design Observer, the pair explained why their differences were a strength. 'I am practical, Massimo is creative, but he is disorganised,' noted Lella. Massiomo added, 'Lella is my brake, my reality, I could not have done this without her.'

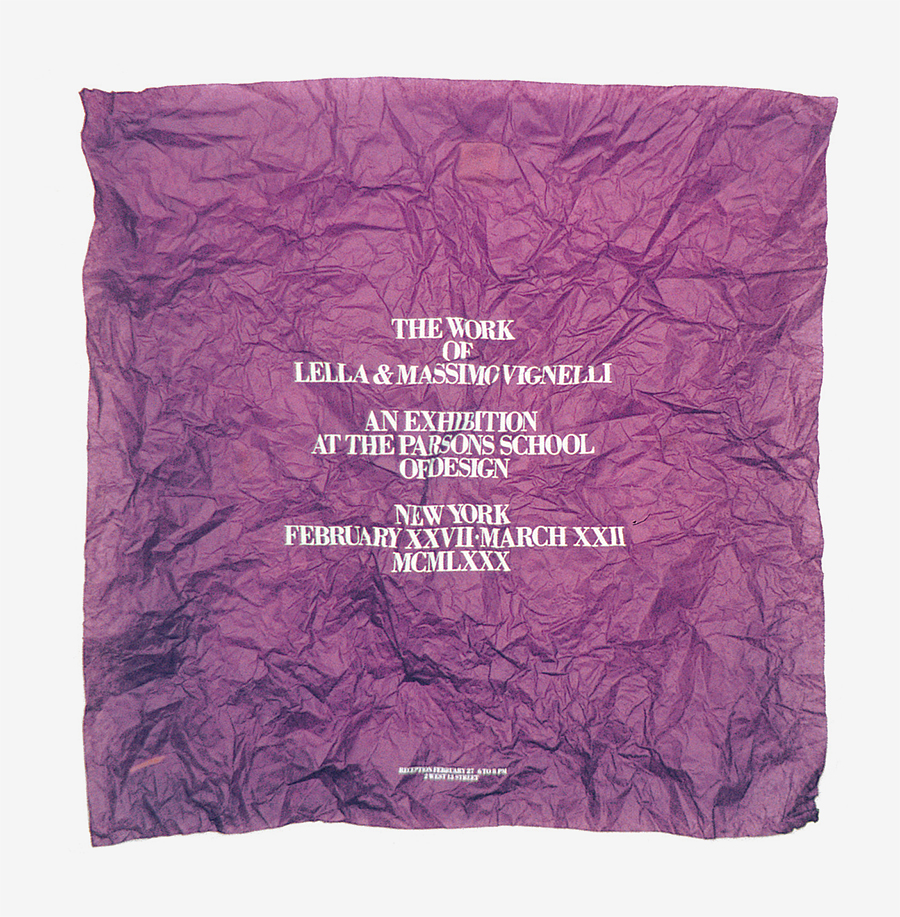

An invitation for an exhibition at the Parsons School of Design, 1979

In Designed by: Lella Vignelli, published in 2013 and marking five decades of their partnership, Massimo explicitly acknowledged the historical erasure of women’s contributions within mixed-gender studios. He cited partnerships such as Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand, and Charles and Ray Eames – collaborations long recognised but rarely credited with equal authority. The book deliberately foregrounded projects authored entirely by Lella alongside those produced jointly, repositioning her not as a supporting figure but as a designer of independent vision, authority and rigour.

Designing behaviour, not just things

Across furniture, interiors and exhibitions, the Vignellis returned to the idea of involving the user. Tables with interchangeable bases, modular seating, and adaptable store layouts all reflected what they described as a constant oscillation 'between identity and diversity'. Their design for the interior of St Peter’s Church in New York exemplifies this thinking. Conceived around a central altar, the church features movable pews and a baptismal font encircled by steps, allowing the space to be reconfigured according to use – a radical idea within a typology traditionally defined by fixity.

Even in domestic objects, the same logic applied. Oven dishes where the rim became a handle; stacking tableware designed for efficiency rather than display; furniture intended to sit in the middle of a room rather than against a wall. These were not stylistic gestures, but attempts to align form with lived behaviour.

Legacy

In 2000, when the lease expired on their large office on Tenth Avenue, the Vignellis chose to downsize dramatically, reducing the studio from around 50 people to just themselves and three others, while continuing to work at the same intensity. Their professional partnership, spanning more than five decades, was later brought to an abrupt end when Lella was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, with Massimo becoming her carer in the final years of their lives.

Massimo Vignelli died in 2014, aged 83, and Lella followed two years later, in 2016, at the age of 82. Yet the ideas they articulated – about responsibility, clarity and generosity – continue to circulate widely. Less a legacy of individual masterpieces than of a way of thinking, their work reminds us that the most enduring design is often the least conspicuous: the systems we move through daily, the objects that earn our trust, and a belief that good design, done properly, should feel as though it has always been there.

Launched in 2014, the ‘Vignelli’ rocker was Lella and Massimo’s final chair design. It features distinct fluid curves that create the cleanly defined, sculptural shape of an armchair that gently rocks back and forth. For use indoors and outdoors, its matte finish is available in three colours.

‘Lella e Massimo Vignelli’ runs from 25 March to 6 September 2026, Triennale Milano, Viale Alemagna 6, Milan

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.