How Charles and Ray Eames combined problem solving with humour and playfulness to create some of the most enduring furniture designs of modern times

Everything you need to know about Charles and Ray Eames, the American design giants who revolutionised the concept of design for everyday life with humour and integrity

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The name ‘Eames’ has become inextricably linked to the idea of good design – specifically, great furniture. It’s a mark of status to have an Eames chair (ah, but which one?) and to know of the story behind the name is to know perhaps the greatest partnership in love and work to contribute to the history of design.

A married couple, Charles Eames (1907–1978) and Ray Eames (1912–1988) wanted everyone to have good design in their lives. Though the duo’s furniture designs may now be luxury products, at the time the work was underpinned by a democratic instinct. Indeed, as the Eameses’ mission statement explained: ‘We want to make the best, for the most, for the least.’

Drawing on a Bauhaus ethos of functionalism, theirs was a design of precision, in which everything worked together efficiently and effectively – with chairs the primary medium – though never at the expense of comfort or style.

The Eameses set out to be problem solvers, not auteurs, and material innovation drove much of their output, from early experiments in bent plywood to later developments using plastic. What resulted is a body of work that came to define mid-century American interiors – and far beyond.

Charles and Ray Eames

Charles (born Charles Eames Jr) and Ray (born Bearnice Alexandra Kaiser) met in 1940 at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan. Charles had previously studied architecture at Washington University, and Ray had studied painting in New York where she became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group.

At Cranbrook, Ray parlayed a design fellowship into becoming the school’s first director of the industrial design programme, while Ray enrolled in various courses to expand her oeuvre.

The seed of the material exploration that would go on to define the Eameses’ practice was planted in these early days, when Charles and his good friend Eero Saarinen entered into and won a furniture competition organised by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), ‘Organic Design in Home Furnishings’, by moulding a single piece of plywood into a chair (Ray worked on the graphic design for the entry).

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charles and Ray fell in love, and were married in 1941 following his divorce from first wife Catherine Woermann (with whom he had a daughter, Lucia, born 1930). The couple moved to a Richard Neutra-designed apartment in Los Angeles and continued experimenting with moulding plywood into furniture in their spare bedroom, drawn to its potential as a lightweight and affordable material. It was here where they built a plywood-curing oven, ‘Kazam!’, which produced their first bent-plywood seat shell.

Design as a tool for innovation in times of need

Eames Leg Splint, 1941-1942

After the US joined the Second World War in December 1941, Charles and Ray applied their material innovations to war efforts. Responding to the need for improved emergency transport splints in combat zones, the Eameses developed a lightweight, stackable leg splint for wounded soldiers made from moulded plywood.

The US Navy’s funding for the splints enabled Charles and Ray to pursue mass-produced furniture and set up a workspace in Venice, California. Their first major product was the Lounge Chair Wood (LCW, 1945/6). The simple, low-lying, bent plywood chair tilts back slightly, with a curved supporting back rest. It aimed to be an affordable, comfortable option for households across America.

DCW, a dining version of their earlier LCW, from the 1940s

The Eames Office, Charles and Ray’s formal design studio, was officially launched in 1947. When Herman Miller began to manufacture the Eames Office designs, the furniture quickly spread across the country. Many believe it was the go-to furniture for the emerging and suburbanising postwar American middle class.

A new idea for modern living

Around the same time, Charles and Ray were busy building the home that would go on to define both their lives and legacy: Case Study House 8, now known as the Eames House. Located in the Pacific Palisades, California, the home initially responded to the Case Study House Program, an initiative organised by Arts & Architecture magazine to prototype affordable modern homes in the wake of the postwar housing shortage.

What resulted was a modernist building of steel and glass, with patches of primary colours on its geometric exterior like an architectural translation of a Mondrian painting. Surrounded by a eucalyptus grove and meadow, it overlooked the Pacific Ocean.

Expansive glazing brought generous daylight to the interiors, populated by the Eameses’ eclectic art and design collection. A double-height living space and adaptable floor plan enabled the flexibility of modern creative life to play out. A smaller building in the same style was also built next to the home, used as the couple’s studio. Charles and Ray moved in on Christmas Eve, 1949, and lived there for the rest of their lives.

Design icons from Charles and Ray Eames

Back at the Eames Office, the duo expanded their explorations into materiality, embracing metal as well as innovative plastic to make mass-produced, useful furniture. Their Plastic Side Chair (1950) and Wire Chair (1951) are particularly celebrated designs from this era. With practicality in mind, they produced versions of most of their designs – with varying finishes, materials or configurations such as chair leg styles – to appeal to the broadest possible market.

Lounge Chair and Ottoman

Charles and Ray moved beyond furniture into homeware too, blending function with playfulness with the Hang it All hook rack (1953), a colourful coat rack still found in many a design-conscious household today.

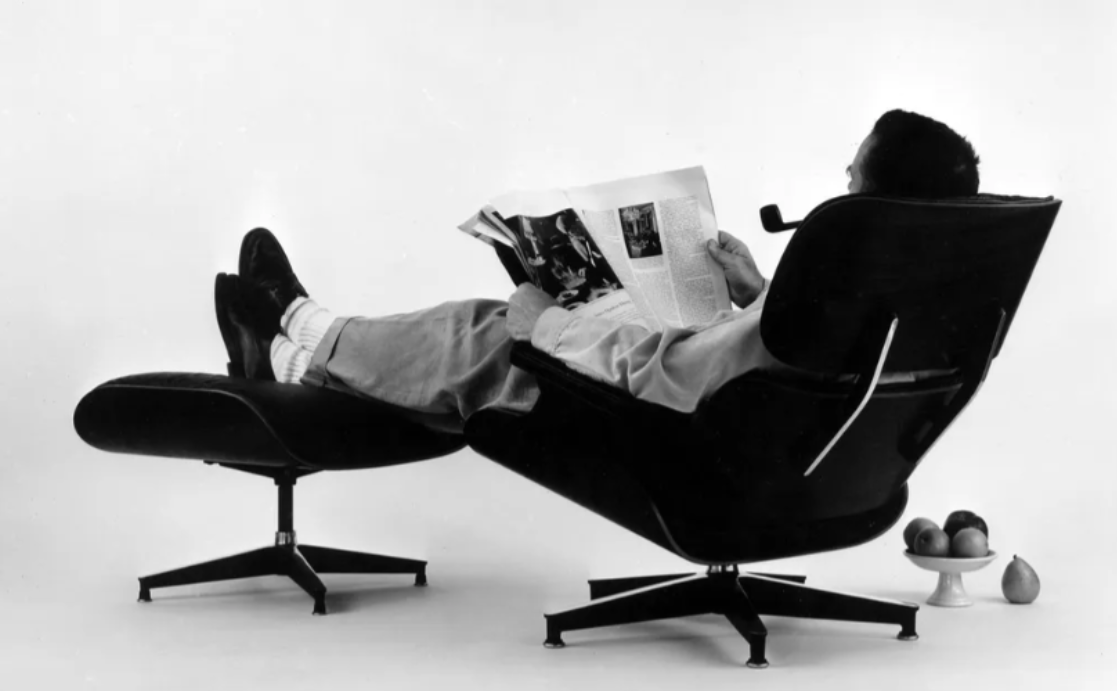

In 1956, the duo created perhaps their most iconic creation: the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman. Combining elegance, practicality and sumptuous comfort, the tilted-back chair and accompanying minimal ottoman fills curved plywood planes with leather or fabric-covered upholstery. It signalled a new direction for ergonomic furniture.

Aluminium Group, part of the Eameses' office chair output

In 1957, Vitra signed an agreement with Herman Miller to produce the Eameses' designs for Europe and the Middle East. Herman Miller and Vitra remain the only licensed manufacturers of Eames furniture and products.

As American office culture grew in the 1950s and 1960s, so the Eameses turned their attention to simple yet stylish and comfortable designs to furnish the workplace – including the Aluminium Group (1958) and Soft Pad Group (1969) of chairs, blending aluminium frames with soft upholstery.

The Eameses also designed toys, fabric patterns, international exhibitions and produced short films – including the influential ‘Powers of Ten’ (1968; re-released 1977), in which orders of magnitude based on a factor of 10 are demonstrated by visually zooming away from the earth to the edge of the universe, and then in to the nucleus of a carbon atom.

The Eames legacy

Charles died in 1978; a year later, the couple was awarded (partly posthumously) the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Royal Gold Medal. After Ray died in 1988, the Eames family worked to secure the duo’s legacy through the Eames Office – subsequently dedicated to the preservation and communication of Charles and Ray’s designs.

Charles’ daughter, Lucia Eames, established the Eames Foundation in 2004 to ensure the sustainable future of the Eames House, which became a National Historic Monument and is now open to the public via bookable tours. The body has since become the Charles & Ray Eames Foundation, and organises cultural Eames initiatives worldwide in addition to being custodian of the house.

The Eames Institute Institute of Infinite Curiosity

The Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity, established in 2022, looks after Charles and Ray’s archives and collection – tens of thousands of artefacts – and makes it accessible to the public, in Richmond, California. The institute, whose chief curator is Charles’ granddaughter Llisa Demetrios, is now working on opening a new design museum in Novato, California, where the Eames collection will feature alongside a range of other collections and exhibitions.

The Eames works to know (and own)

Along with the Plastic Side Chair (below), the Plastic Armchair was the very first mass-produced plastic chair in the history of furniture. It realised the Eameses’ desire to mould a single shell to the contours of the human body, with their material experimentation leading them to glass fibre-reinforced polyester resin. Practical, comfortable and easy to clean, the chairs lent themselves to a variety of contexts. A rocking version on curved wooden runners infuses the design with playfulness. These days, with a greater understanding of virgin plastic’s negative impact on the environment, the Eames Plastic Chairs are manufactured from recycled material.

The Plastic Side Chair has become ubiquitous – a familiar feature of classrooms, offices, public institutions and homes. Simple and yet supportive, the design includes multiple variations including a stackable version (DSS-N), enhancing its appeal for large group gatherings.

Instantly recognisable for its metal grid appearance, the wire chair continued the notion of moulding material to the human body but looked instead to uncompromising welded steel wire to do the job. While the version without upholstery is divisive – comfort is not precisely its USP – the design with diamond-like seat and back padding (colloquially called the ‘Bikini’ pad) unites iconic design with a softer sitting experience.

Appearing like a cacophony of colourful notes on sheet music, the Hang it All rack infuses the otherwise mundane routine of hanging up coats into an experience dotted with delight. Though it may have initially been aimed at children, the design – featuring wooden sphere-topped hooks on a steel wall-mounted frame – soon became popular across all ages.

An icon of mid-century design, the lounge chair and ottoman brought together the couple’s long-term explorations into moulded plywood with a celebration of true comfort. Focused on relaxation – to quite literally put your feet up – the design was nonetheless sleek and elegant, with nothing superfluous.

A small, low chair, the LCW comprises clean-lined, bent plywood planes. The seat was reportedly inspired by the gentle curve of a potato chip. Designed for relaxation, the chair leans back and can be upholstered with leather. Different versions of the design, within the Plywood Group of chairs, include taller, dining chair proportions and a tubular steel frame.

If you’ve spent much time in airports, chances are you’ll recognise the Tandem seating that the Eameses designed. Combining sleek aluminium base and frames with black leather seats and armrests, the tandem seating was designed for waiting areas – specifically, for Dulles Airport terminal in Washington, DC that the Eameses’ friend Eero Saarinen designed in 1962. It was soon in demand everywhere. As ever with Charles and Ray’s creations, the design struck the perfect balance between durability and comfort.

Francesca Perry is a London-based writer and editor covering design and culture. She has written for the Financial Times, CNN, The New York Times and Wired. She is the former editor of ICON magazine and a former editor at The Guardian.