Gio Ponti: the complete visionary

Architect, designer, writer and eternal optimist, Gio Ponti brought light, colour and joy to the modern world – uniting Italy's artistic past with its industrial future.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

A father figure of Italian design, Gio Ponti (1891–1979) embodied the postwar spirit of optimism and invention. Born and raised in Milan, he studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano after serving in the First World War. His career went on to span architecture, furniture, industrial design and publishing, each approached with the same blend of rigour, curiosity and joy. For Ponti, creativity was a way of life rather than a profession – an act of continuous observation, drawing and making. He famously said: 'The most resistant element is not wood, is not stone, is not steel, is not glass. The most resistant element in building is art. Let's make something very beautiful.'

'Diavolo' sculpture, 1978

Furniture for Casa di Fantasia, 1951

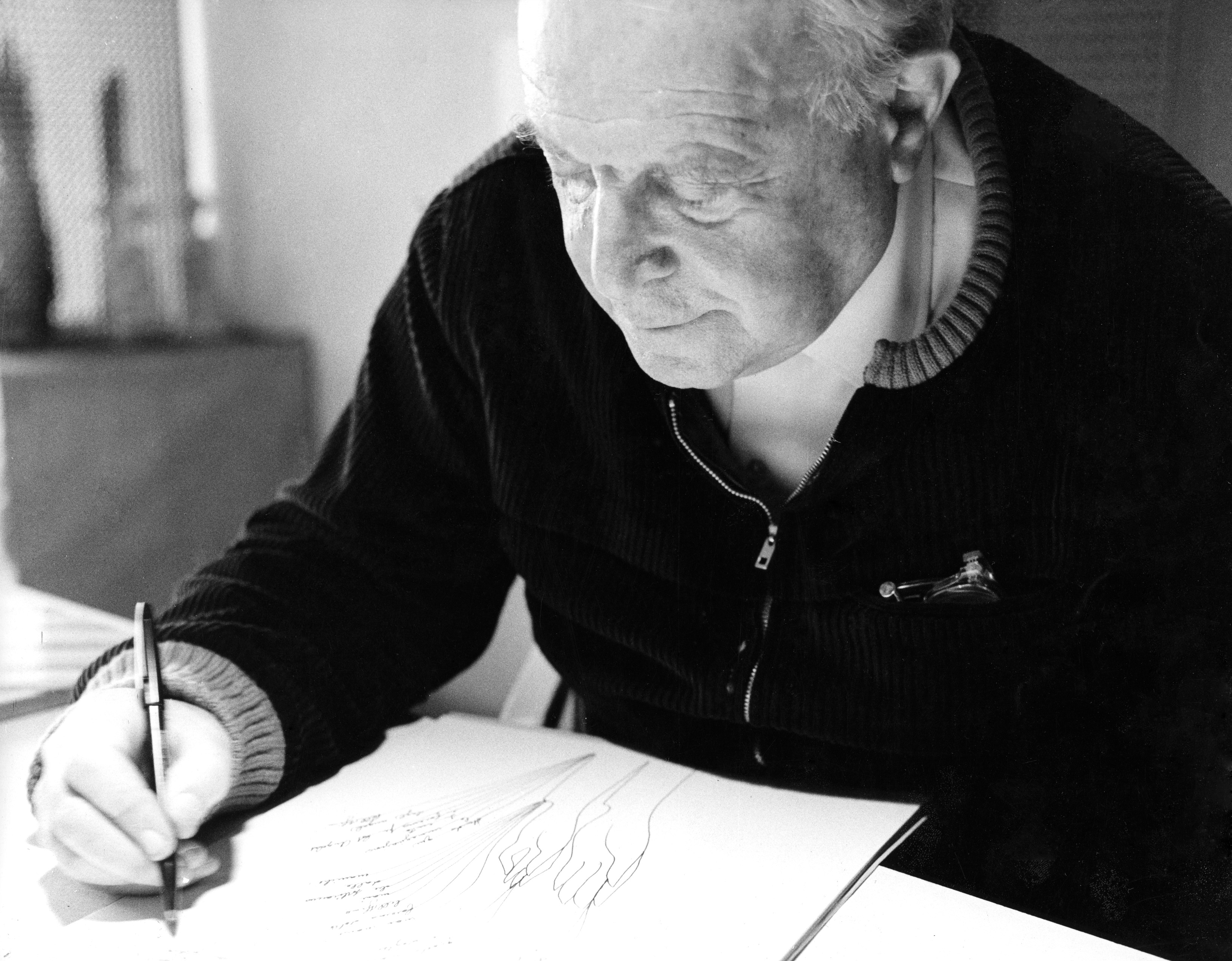

In Molteni’s documentary Loving Gio Ponti, his daughter Lisa Licitra Ponti remembered him as cheerful but strict, while the late artist Nanda Vigo recalled how he would rise at dawn to draw in bed before breakfast – the kind of daily discipline and passion for his work that defined his prolific, six-decade career.

Gio Ponti furniture from Molteni & C: D.355.1/D.355.2 suspended bookshelf, D.552.2 coffee table and D.153.1 armchair

Enzo Mari credited him with 'jump-starting' development in Italy when the country was at its lowest point after the war, championing a new alliance between craftsmanship, art and production. His was a life dedicated to beauty in all its forms: from porcelain to skyscrapers, from publishing to poetry.

Gio Ponti: the architect

Pirelli building, 1959

Ponti’s architecture evolved throughout his life, from the classical symmetry of his early houses to the poised modernism of his later work. Yet even at his most rational, his buildings retained a sense of lyricism and light.

Apartment on Via Dezza, 1957

His own apartment on Via Dezza in Milan (1957) served as a testing ground for his ideas on modern living: a compact, flexible home of around 100 square metres, partitioned by sliding panels or 'accordion' doors and animated by a warm yellow palette, striped Melotti floors, and carefully orchestrated light. Ponti’s embrace of open-plan living was decades ahead of its time, reflecting his belief in spaces that could adapt to the rhythms of modern life.

Montecatini Building, 1936–38

The Montecatini Building (1936–38) – designed with Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini – marked one of the first instances of total design in Italy – Ponti conceived everything from the marble facade to the office furniture and even technological systems.

Two decades later came the Pirelli Tower (1958), which still towers above Milan today. Designed with Pier Luigi Nervi, it is a postwar symbol of Italian ingenuity whose aerodynamic profile Ponti likened to the wing of an aeroplane. 'This building was born young,' he said, 'and it never will age, because simplicity is a virtue that cannot be bettered.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The designer

Ponti’s design career began in the early 1920s when, fresh from university, he joined the historic porcelain maker Richard Ginori. Despite being young and inexperienced, he succeeded in revitalising the company’s fortunes by infusing traditional craftsmanship with surreal and painterly motifs – a union of art and industry that would define his approach.

It was at Ginori that he developed a fascination with the human hand – a motif that continued to resurface throughout his career, notably in his interiors and decorative arts of the 1960s. 'Ponti's hand represents the human ability to imagine, to go beyond the world of objects to enter those of theatre, poetry, and playfulness,' explains Salvatore Licitra, curator of the Gio Ponti Archives. 'They are a tribute to the craftsmanship of the artist's and ceramicist's ability to animate matter with his own hands.'

Furniture, for Ponti, was architecture in miniature. His Leggera chair (1951) for Cassina reimagined the humble Chiavari chair in slender ash and paved the way for his Superleggera (1957), which pushed the idea of lightness to its extreme. Weighing just 1.7kg, it was advertised being lifted with a child’s little finger, and was strong enough to withstand being thrown by Ponti from a fourth storey apartment building without breaking, so the story goes. For Ponti, true modernity lay in this poetic precision: objects reduced to their essence, yet never stripped of charm or humanity.

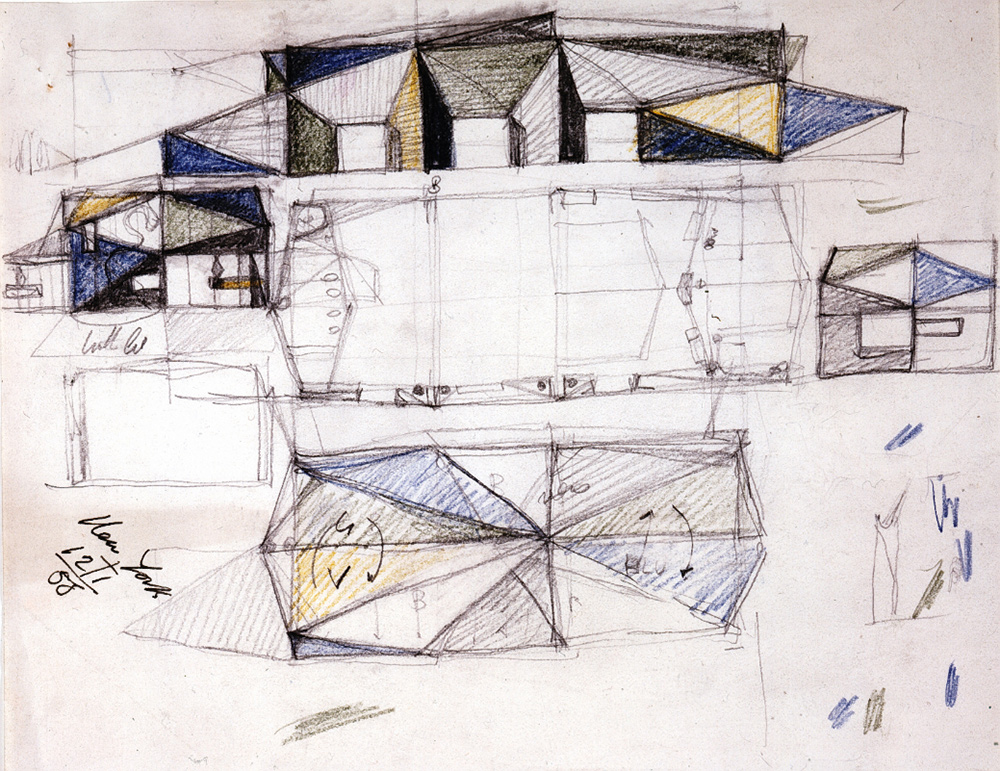

A sketch of the Time & Life Building’s auditorium. Archive image: courtesy of Gio Ponti Archives

D.859.1 table from Molteni & C

Architecture and design often merged seamlessly in his work. Take his ‘D.859.1’ table, which was originally designed as the centrepiece of his most extensive project in New York: an auditorium on the eighth-floor terrace of Harrison & Abramovitz's Time & Life Building. When it first opened its doors in 1959, Ponti's auditorium was the ultimate gathering place for the sharply suited businessman and the stage of high powered business meetings for Henry Luce’s Time Inc, then at the apex of a mighty media industry. Keen to establish his reputation in the US, Ponti used the commission to introduce a distilled vision of Italian modernity – light, elegant and unapologetically cultured – into a corporate setting.

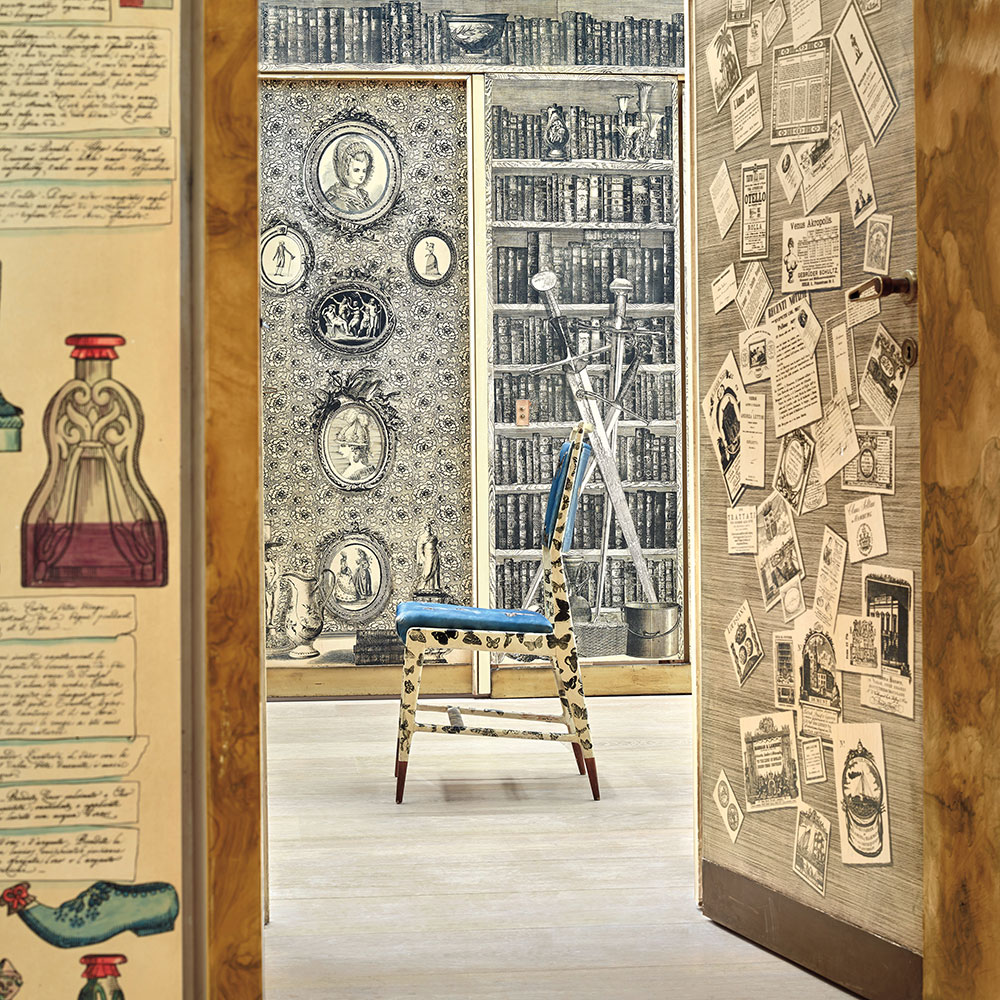

Furniture for Casa di Fantasia

Over his career he developed products for more than 120 companies, including typewriters, cutlery and even sanitaryware. Nothing escaped his eye – or his conviction that beauty should permeate every aspect of daily life.

The publisher

If Ponti helped define modern Italian design, Domus, the magazine he founded in 1928, gave it a voice. Still published today, the publicatrion is widely regarded as one of the most influential and first internationally successful Italian design and architecture magazines. Across more than 500 issues, Ponti celebrated his peers and protégés – among them Carlo Mollino, Lucio Fontana and Piero Fornasetti – and positioned design as a cultural pursuit rather than a commercial one.

As an editor and teacher, he was curious, generous and open-minded, even in old age seeking out younger figures like Alessandro Mendini and Ettore Sottsass. His writing radiated the same clarity as his drawings, often returning to a single belief: that architects must learn from artisans.

In his 1960 book In Praise of Architecture, Ponti urged architects to 'learn from all the artisans – from the marble cutter, the carpenter, the plasterer, the blacksmith – from all workers and craftsmen. Let him learn things made with the hands; nothing is born that is not first in the hands.'

Five Ponti masterpieces to know

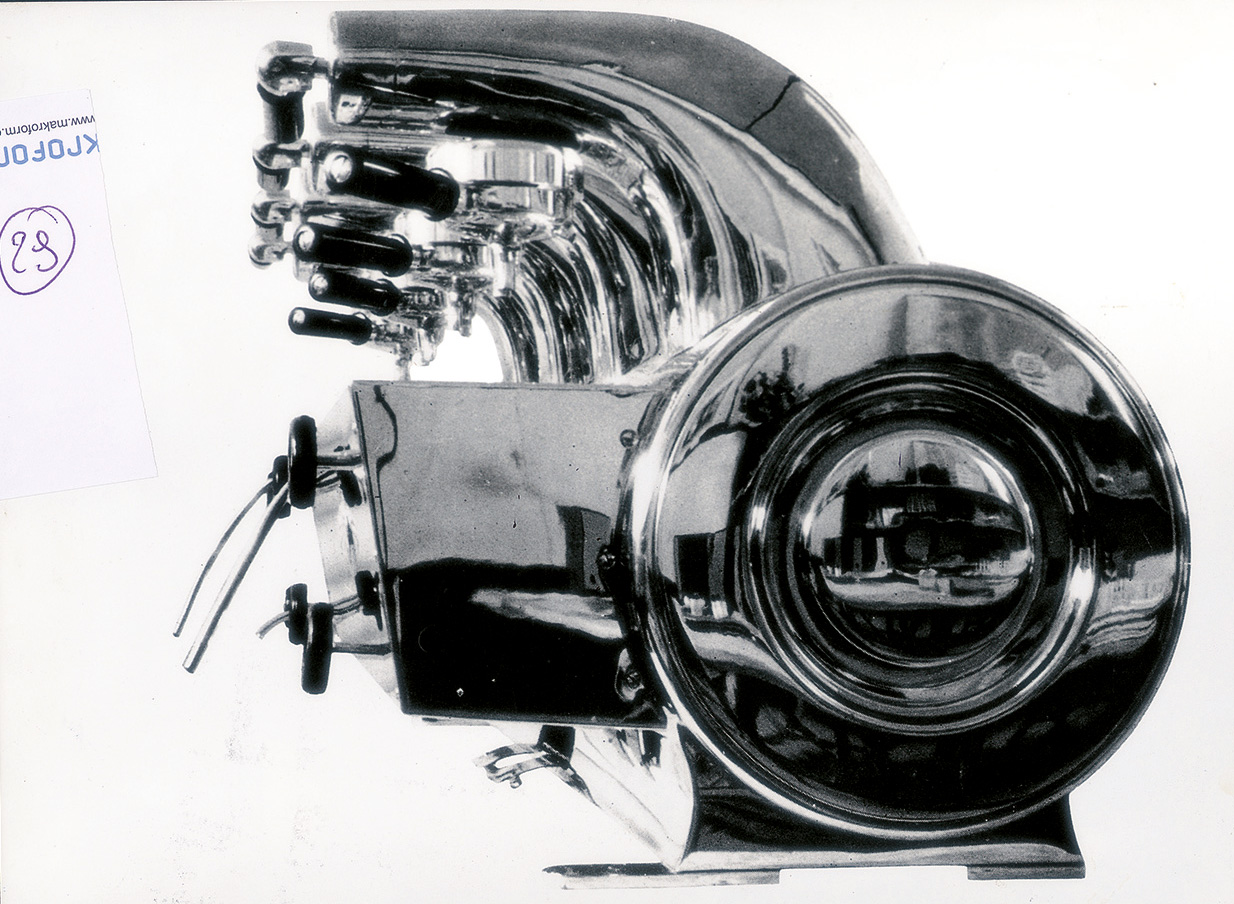

La Cornuta Espresso Machine (1948)

Sculptural and voluptuous, designed for Pavoni as both tool and totem of modern life. Ponti was the first to adopt a horizontal layout for the espresso machine, replacing the traditional vertical boiler with a sleeker, more ergonomic form that anticipated the modern cafe bar aesthetic.

Dezza Armchair (1965)

Special edition illustrated Dezza armchair from Poltrona Frau, on the occasion of the design's 60th anniversary

With its modernist, squared lines balanced by curved armrests and slender, tapered legs, the Dezza’s design conveys a sense of movement. As a testament to its enduring appeal, it has remained in continuous production since its debut.

Villa Planchart, Caracas (1955)

Perched 'like a butterfly' above the Venezuelan city, the Villa Planchart was commissioned by art collectors Anala and Armando Planchart. It is a quintessential example of Ponti's 'humanistic modernism' and a total work of art – a Gesamtkunstwerk – where he designed the architecture, all the custom furniture, and many of the objects and details within it.

Hotel Parco dei Principi, Sorrento (1962)

In the 1960s, Ponti was at a late but highly productive stage in his career, still actively working across architecture, design, and publishing. This clifftop hotel is a blue-and-white Mediterranean masterpiece tiled with thirty unique ceramic patterns that remain in tact to this day.

Cathedral of Taranto (1964–70)

The Concattedrale Gran Madre di Dio in Taranto is a lesser-known Ponti project from late in his career, featuring a 40-metre-high concrete facade recalling a sail, pierced with crosses and flooding the interior with southern light. The cathedral pays tribute to Taranto’s maritime heritage while distilling Ponti’s fascination with structure, symbolism and spirit.

Legacy

Ponti’s independence often put him at odds with his peers. Critics dismissed him as a 'stylist', yet it was precisely his independent spirit and refusal to follow dogma that made him timeless. He believed that beauty was not a luxury, but a human necessity – a conviction visible in every drawing, chair, and facade he touched.

'Essentialità' was one of Gio Ponti’s favourite words, and it’s key to understanding his whole philosophy. When Ponti spoke about 'essentiality' (l’essenzialità), he didn’t mean minimalism in the sense of stripping things bare. Rather, he meant arriving at the purest possible expression of an idea – removing excess until only what is vital, meaningful and joyful remains.

A sketch of the auditorium in New York's Time & Life Building. Archive image: courtesy of Gio Ponti Archives

His hand continues to shape lives through the buildings and products he designed, many of which remain in production today with brands including Molteni & C, Poltrona Frau, Cassina, and Richard Ginori – a testament to the enduring clarity of his vision.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.