When did we stop dreaming of a better future? A new book presents four hopeful scenarios

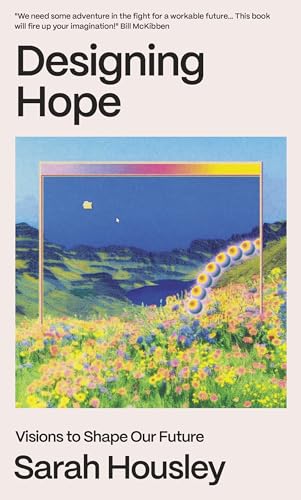

In her debut book, ‘Designing Hope’, Sarah Housley explores how design might help create more equitable, inclusive and radically liveable futures

'Our feelings about the future have become complicated and troubled,' says London-based design futurist Sarah Housley. 'We live in the present culturally, and when the future is mentioned it's often in the context of climate collapse or potential crises such as AI displacing jobs or slowing population growth.'

Formerly head of Consumer Technology at trend forecasting company WGSN, Housley spent more than a decade charting cultural and technological change – from the rise of lab-grown meat to our evolving relationships with robots – always probing the why and how behind these shifts.

Housley worked for more than a decade at trend forecasting company WGSN where she held the title of head of Consumer Technology

Now, leading her own consultancy, she has authored Designing Hope (Indigo Press), a book that interrogates her field of specialism – design futures – and presents four visionary scenarios for a more hopeful outlook. Her visions span multispecies design, wellbeing economies, renewable coexistence with nature, and entirely virtual worlds. Each is grounded in real projects by designers, artists and thinkers already laying the foundations.

The book, Housley says, is intended as a 'jumping-off point' – a call to action for readers to imagine the futures they want and consider how they might help bring them into being.

Sarah Housley on designing a better tomorrow

One of the imagined futures in Designing Hope is ‘More than Human’, where design is decentered from humanity to serve multiple species. The vision is illustrated by projects such as Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch at Tate Modern, which drew public attention to ecological fragility by placing melting glacial ice in the city

Wallpaper*: Can you explain what is meant by ‘design futures’ and your work in this field?

Sarah Housley: I define design futures very loosely as thinking about the products, experiences and interactions that people will want and need in the future, and how these can be designed. For a researcher like me, that means tracking and synthesising the patterns of change that are emerging today, and analysing how they could come together to shape major change over the next few years or decades. Radical ideas that could alter or disrupt the status quo and business-as-usual thinking are particularly important. One of the things that makes being a design futurist different to being a futurist more broadly is that I focus on translating big ideas from lots of different areas into futures visions that feel tactile, tangible and understandable, so that designers can engage with them and imagine them more clearly.

‘I define design futures very loosely as thinking about the products, experiences and interactions that people will want and need in the future, and how these can be designed’

Sarah Housely

My background is in commercial trend forecasting. I work with brands to explore a range of design futures and what the implications of change will be for them and the products they make – and how they can drive positive change. I also work with charities, NGOs and cultural institutes to think about their futures and teach them futures thinking tools and processes.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The ‘Degrowth’ section in the book envisions a future where economic expansion gives way to human wellbeing and sustainable use of resources, prompting us to live with the remnants of the past. The vision is embodied in projects such as Smile Plastics’ work surfaces, made from waste materials including recycled tinsel

W*: In the book’s intro, you highlight 2016 – a year of seismic geopolitical shifts – as the moment when excitement about the future gave way to anxiety. Why was it important for you to write a book about hope in this moment?

SH: Our feelings about the future have become complicated and troubled. We live in the present culturally and when we do see the future mentioned, it's often in the context of climate collapse or reports on potential crises like AI displacing jobs, or rates of population growth slowing down. Outside of the field I work in, alternative futures are not often discussed, and that's made the mainstream idea we have of the future very limited and dystopian. Hope always has to come with action and with critical thinking, and that's the mindset that drives the book: I wanted to introduce creativity and possibility. Quite simply, I saw a lot of narratives about people feeling very anxious about the future and there being a crisis of imagination, and thought that I could widen out the conversation.

‘Hope always has to come with action and with critical thinking, and that's the mindset that drives the book: I wanted to introduce possibility’

Sarah Housley

W*: You acknowledge how futures thinking has historically carried a WEIRD bias (Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic). Can you explain why it was important for the book to consider multiple perspectives and more than one possible future?

SH: Futures visions really benefit from being co-created. As futures thinking becomes more diverse, it is becoming not only more interesting, but a lot more relevant to a lot more people. I always use the plural 'futures', for a few reasons: first of all, there won't be just one future, and to introduce that sense of possibility that is so important in design futures, we need to consider lots of different ideas, perspectives and prospects. Using the plural also reminds us constantly that the future is not inevitable; we can redesign it. We always have a choice.

The book's ‘Solarpunk’ vision imagines a utopian Anthropocene, where renewable energy enables humans to coexist with nature. Housley highlights emerging circular solutions designed to make homesteads more self-sufficient, such as the 'Harvest Moon Luna' compost toilet by Rebecca Schedler

W*: The book closes with a set of six practical exercises. Why did you want to include these, and what do you hope readers take away from them?

SH: I wanted the book to be really interactive and to invite the person reading it to have their own reactions and ideas throughout. The exercises at the end make that very clear and they offer a few different ways to be creative: you can write a short story, a narrative, or create a drawing or a physical object. They also encourage you to commit to a change or an action. Futures thinking has to become active to become effective: it's a way of driving change, whether that's changing someone's mind, changing their behaviour or altering their whole worldview.

Refik Anadol’s Large Nature Model artwork is highlighted in the book's ‘Metaverse’ section, a vision of a future that imagines life lived largely in virtual worlds. In this vision, immersive technologies reshape how we experience nature, community and creativity

W*: On a personal level, what motivated you to write Designing Hope, and has your own perspective evolved during or since the process of writing it?

SH: I find futures thinking really fascinating and partly I wanted to share that fascination and make more people aware of what people like me do and how we do it. I see futures thinking as a teachable skill – I do teach it, in fact, in workshops and at universities – and I've seen time and again how it can motivate people and excite and inspire them. I personally get frustrated by dystopia and although I'm very cautious of false positivity, there is so much innovation happening and so much to be curious and hopeful about.

‘There is so much innovation happening and so much to be curious and hopeful about’

Sarah Housely

Writing the book strengthened my conviction that we have the tools and solutions that we need to create more inclusive, equitable and compelling futures, and to bring them into being; that positive change is still possible and that people can come together to create it. There's so much we can do. One of my favourite definitions of hope describes it as reframing perspectives: that's what the best futures thinking does.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

Chef Ray Garcia brings Broken Spanish back to life on LA’s Westside

Chef Ray Garcia brings Broken Spanish back to life on LA’s WestsideClosed during the pandemic, Broken Spanish lives again in spirit as Ray Garcia reopens the conversation with modern Mexican cooking and layered interiors

-

Inside a skyrise Mumbai apartment, where ancient Indian design principles adds a personal take on contemporary luxury

Inside a skyrise Mumbai apartment, where ancient Indian design principles adds a personal take on contemporary luxuryDesigned by Dieter Vander Velpen, Three Sixty Degree West in Mumbai is an elegant interplay of scale, texture and movement, against the backdrop of an urban vista

-

A bespoke studio space makes for a perfect architectural showcase in Hampshire

A bespoke studio space makes for a perfect architectural showcase in HampshireWinchester-based architects McLean Quinlan believe their new finely crafted bespoke studio provides the ultimate demonstration of their approach to design

-

Tour the world’s best libraries in this new book

Tour the world’s best libraries in this new bookAuthor Léa Teuscher takes us on a tour of some of the world's best libraries, from architect-designed temples of culture to local grassroots initiatives

-

Irma Boom on books and beyond – meet the Dutch graphic design legend in her studio

Irma Boom on books and beyond – meet the Dutch graphic design legend in her studioA pioneering force in the world of print, Boom welcomes us to her Amsterdam studio to discuss the infinite possibilities of book design, curious heroines and holy encounters

-

Martino Gamper transforms Nilufar Depot into a live workshop for the gallery’s tenth anniversary

Martino Gamper transforms Nilufar Depot into a live workshop for the gallery’s tenth anniversaryNina Yashar celebrates the first decade of Nilufar Depot with a week of live-making by Martino Gamper and a book chronicling the gallery’s extraordinary exhibitions

-

‘Alphabetical Playground’ is a new book about experimental graphics and abstract letterforms

‘Alphabetical Playground’ is a new book about experimental graphics and abstract letterformsNigel Cottier’s new monograph ‘Alphabetical Playground’ explores the creative limits of contemporary typography, delving into tech-driven geometric abstraction

-

Explore the design and history of the humble camping tent in a new book

Explore the design and history of the humble camping tent in a new book‘The Camping Tent’ by Typologie reframes a familiar object, revealing its complexity and cultural weight – and invites us to look at it anew

-

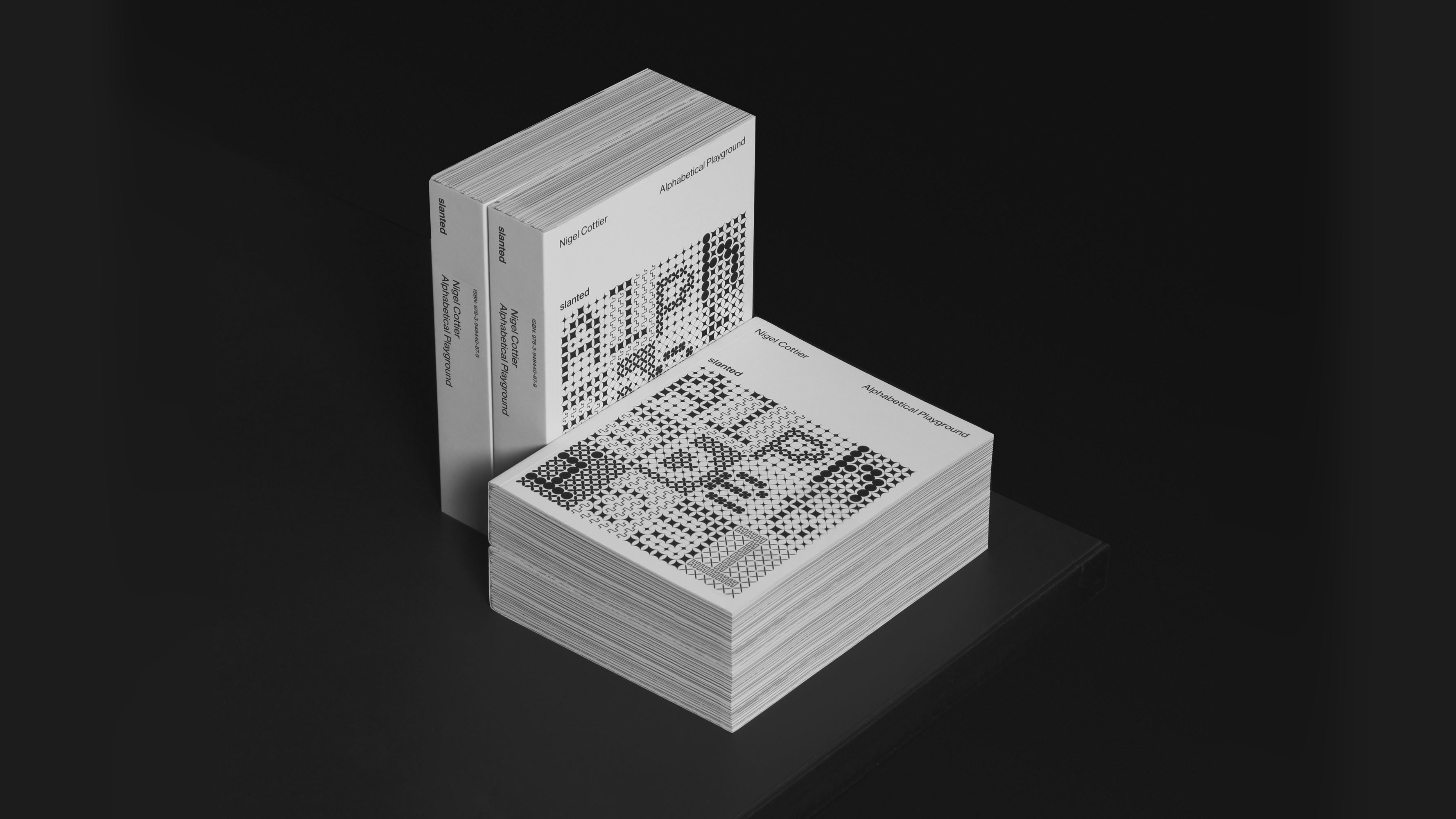

Where writers write: 12 Booker Prize 2025 nominees share their writing spots

Where writers write: 12 Booker Prize 2025 nominees share their writing spotsFrom kitchen tables to bare desks (and even a cemetery bench): 12 writers from the Booker Prize 2025 longlist on their favourite writing set-ups

-

A new book reframes interior design history through a feminist lens

A new book reframes interior design history through a feminist lensDr Jane Hall’s latest book 'Making Space' asserts the significance of interior design, celebrating women who shaped the spaces we live in

-

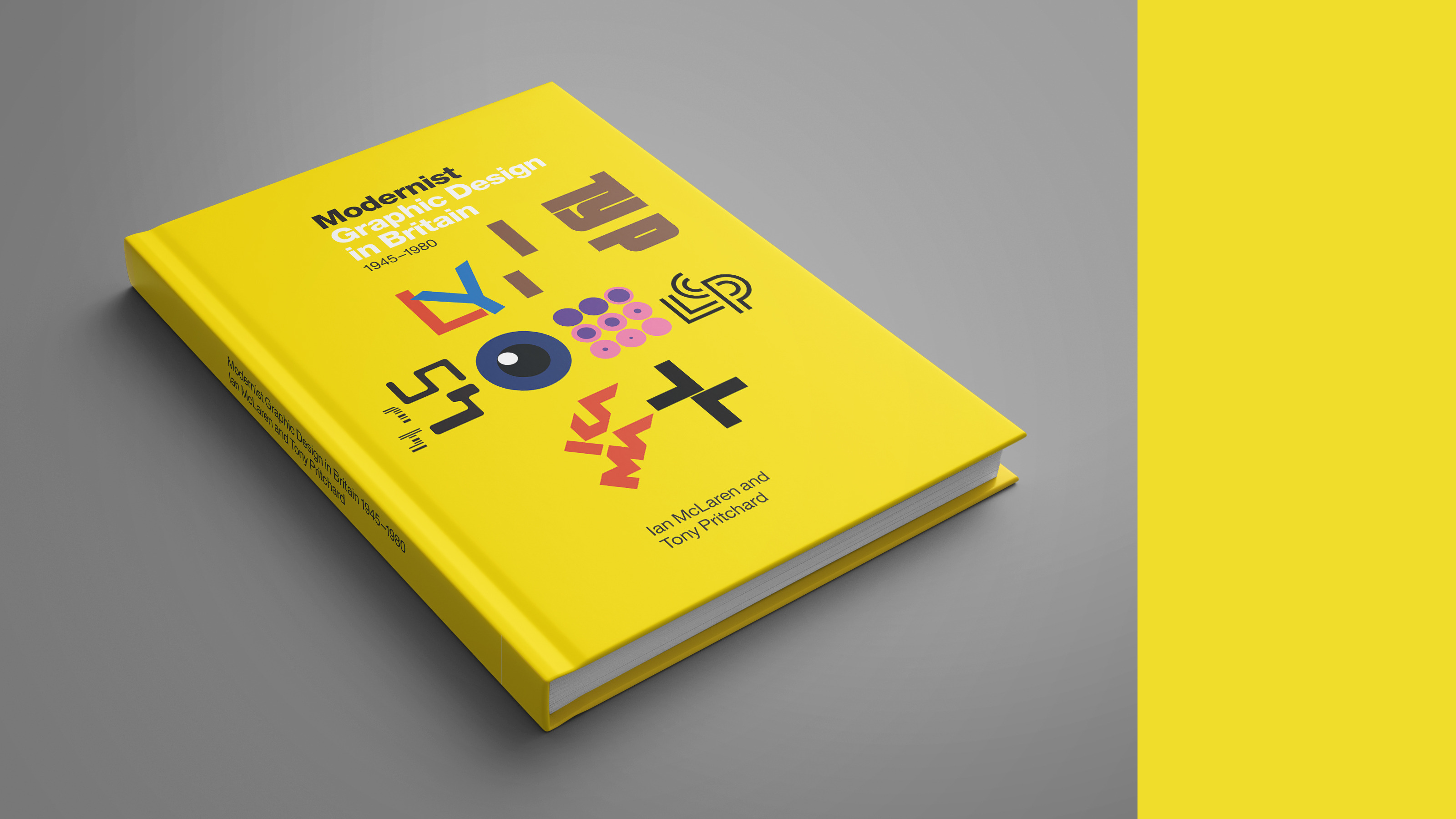

A new book from the Modernist Society focuses on a golden age of British graphic design

A new book from the Modernist Society focuses on a golden age of British graphic design‘Modernist Graphic Design in Britain 1945-1980’ looks at all the ways in which post-war graphic design shaped the nation, from new typography to poster art, book design and more