Ai Weiwei at the Design Museum: a snapshot of design history across eight millennia

Ai Weiwei gathers everything from Neolithic tools to Lego bricks for his new show at London’s Design Museum (until 30 July 2023). We visited him at home in Portugal for a preview

Jermaine Francis - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Ai Weiwei is not known to do things in half measures. For his installation at Documenta 12, in 2007, the artist famously brought 1,001 Chinese citizens to Kassel, Germany, for staggered week-long stays, using his blog to recruit volunteers between the ages of two and 70. Titled Fairytale, the ambitious artwork seemed to herald his homeland’s arrival on the world stage (‘To explore the world is a right that you acquire when you are born, and these travellers were exercising this right for the very first time,’ he wrote in his recent autobiography), while speaking to contemporary global issues, such as mass migration and dramatic population growth. Three years later, invited to take over the Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern, Ai commissioned 1,600 ceramicists in the pottery town of Jingdezhen to handcraft 100 million sunflower seeds in porcelain, which he then poured into the cavernous exhibition space to create a seemingly infinite landscape – a simple motif elevated into a powerful statement on the rise of ‘made in China’.

Ai Weiwei: ‘Making Sense’ at the Design Museum

The artist’s study, with Sunflower Seed in Lego (2018)

Though slightly more modest in scale, the centrepiece of Ai’s exhibition at London’s Design Museum (until 30 July 2023), similarly evokes the cumulative power of the humble object. Taking over the main gallery are five ‘fields’, each between 44 and 72 sq m and filled with readymades ranging from Neolithic stone tools to Lego bricks (see his Water Lilies #1, his largest ever work in Lego), which collectively offer a snapshot of design history across eight millennia.

Titled ‘Making Sense’, this is Ai’s first exhibition focusing on design, which seems surprising coming from a conceptual artist. But Ai has always been fascinated with material culture, an interest that he credits to his life story. The son of Ai Qing, one of modern China’s most famous poets, Weiwei was born in Beijing in 1957. He grew up in the northwest province of Xinjiang as a consequence of his father’s political exile. Denied proper accommodation, the family lived in a dugout – a picture of which remains the lock screen on the artist’s iPhone today – where they slept on a platform covered with wheat stalks, had no electricity, and constantly had to fend off rats and lice. Such squalid conditions necessitated improvisation: Ai remembers assembling a simple shelf from a board, four nails and a piece of string, and building a stove to offer some respite from the bitter winters. These experiences informed his early understanding of design, not as an aesthetic pursuit but as ‘people using rudimentary, found materials to try and better their lives’, he explains on a crisp February morning, as we speak on the back porch of his home in Montemor-o-Novo, Portugal.

Ai’s house was the first property he visited in Portugal. Its tiled roof, similar to those of traditional Chinese buildings, appealed to the artist, who bought the former holiday home on the spot. ‘I didn’t know anything about Portugal. Three years later, I think I made a good decision. I always make big decisions before I know it; it gives me joy to gradually discover everything’

That notion of design as a survival tool was turned on its head when Ai moved to the US in 1981, becoming one of the first Chinese students to study in the West during an era of reform. He wound up in New York (where he briefly attended the Parsons School of Design), which gave him his first experience of ‘extreme capitalism’. But, in 1993, when Ai returned to Beijing to visit his ailing father, he found that China had become a capitalist state too, and was pursuing economic growth at all cost: ‘Even though I’d returned to my native land, I felt more foreign than ever.’

It was then that he began to frequent antique markets with his brother. ‘We spent at least four to six hours every day, going through thousands of pieces and trying to imagine the past. Because of the Cultural Revolution, we never had a history education,’ he explains. ‘And in the United States, everything was new. So these markets gave me the chance to really look into each object. I started to collect, and to understand the past through material culture. I developed an interest in human efforts [at shaping objects]: how they made sense, why they made sense, how they dealt with materials. And how styles completely changed from the Han dynasty to the Tang dynasty, or from the Tang dynasty to the Song dynasty. Then I understood that even a perfect language can completely disappear under different political circumstances. There’s nothing left. That gave me a lot of perspective on the human mind.’

Ai’s Design Museum show will feature Spouts (2015), a ‘field’ of discarded antique teapot spouts (Ai mobilised an entire village in China to amass these)

As his stature and resources have grown, Ai’s collecting has become more prolific over the years. While he says that he only collects things that fascinate him, without regard to their potential usage in art installations, his collections now form the basis of the five fields at the Design Museum. Still Life comprises around 1,800 Neolithic stone tools, liberated from archaeological context. Adjacent, Spouts features over 240,000 spouts from the Song dynasty (960-1279), believed to have been cut off from teapots that didn’t meet quality standards. Nearby is Untitled (Porcelain Balls) (2022), featuring 100,000 porcelain projectiles from a similar period. ‘What fascinates me is that they’re not machine made, they’re handmade with such care, and none of them are exactly the same size, but they’re made to the greatest possible degree of perfection,’ enthuses Ai.

Untitled (Lego Incident) (2015), which refers to Lego’s refusal to supply Ai with bricks to be used in ‘political works’

The final two fields are filled with contemporary materials. The blue porcelain fragments were salvaged from destroyed artworks in the artist’s Beijing studio, which was razed by Chinese authorities in 2018. (His Shanghai studio had likewise been torn down in 2011. In an act of reclamation, Ai is now rebuilding that studio on his Portuguese estate.)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Meanwhile, Lego bricks have been a favoured material for Ai since 2014, when he created Lego portraits of activists, prisoners of conscience, and advocates of free speech from around the world for an installation at Alcatraz. For three months in the following year, the toymaker declined bulk orders from the artist, citing a policy that prevents its bricks from being used in ‘political works’. Ai responded with a crowdsourcing campaign: ‘People supported me by sending in their sons’ and daughters’ Lego bricks. It became a little social movement,’ he remembers. At the Design Museum, the bricks ‘show my understanding of how design not only comes out of our minds, but also exists as a product of human struggle’.

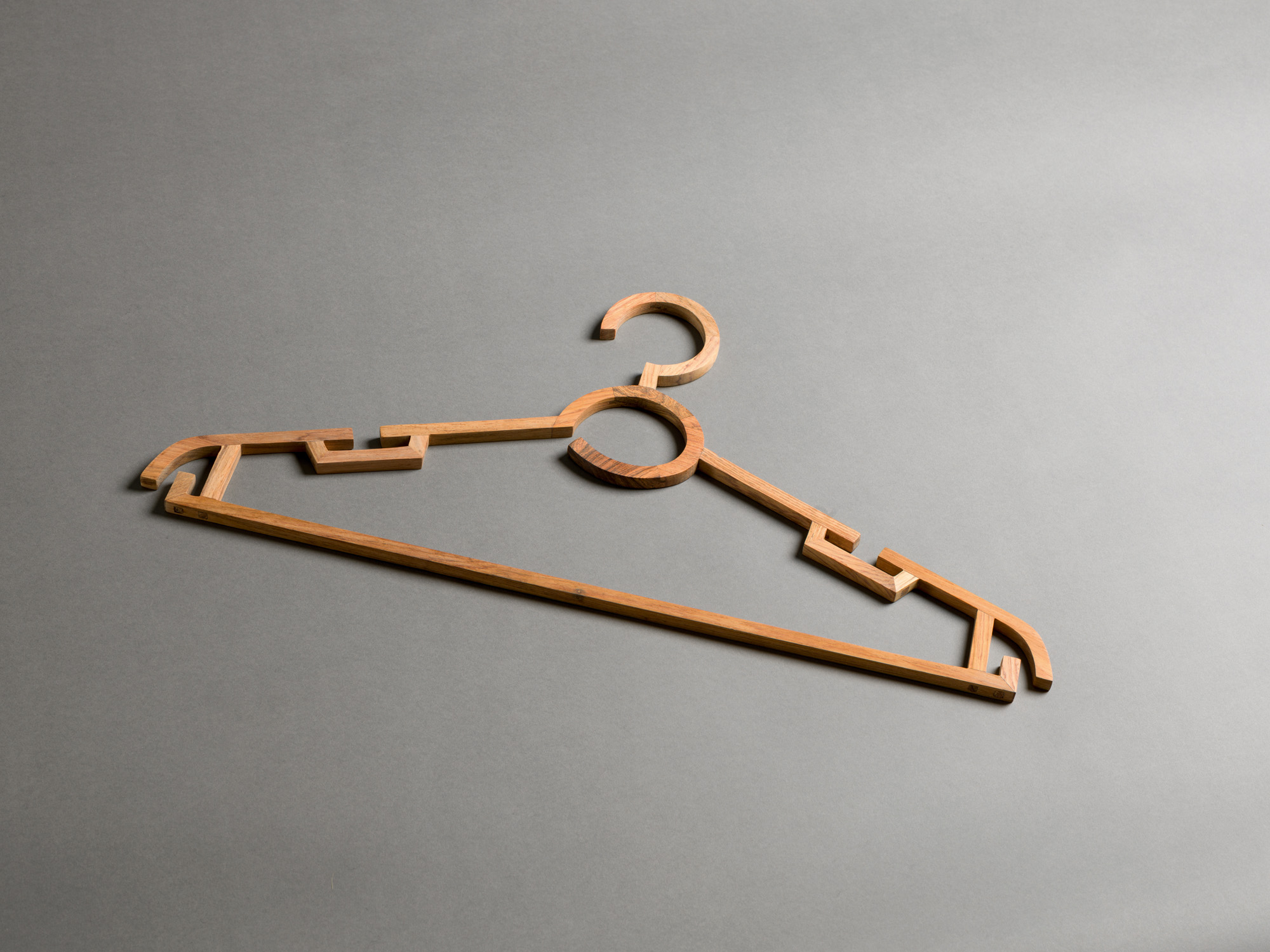

Hanger (2011), a symbol of Ai’s 81 days in detention made using traditional Chinese joinery techniques

In his use of readymades, Ai pays homage to Marcel Duchamp, whom he calls ‘the engineer and designer of modern cultural activity’. He first encountered the French conceptualist’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art when he arrived in the States. Realising that ‘art is in our minds, rather than in our vision’, Ai created Hanging Man (1986), a wire hanger bent in Duchamp’s profile. This is part of the new exhibition, along with three more recent pieces that resemble hangers, alluding to the 81 days in 2011 that Ai spent in secret police detention, for alleged ‘economic crimes’. He petitioned for a month before the police would allow him six plastic hangers, so he could dry his T-shirts. ‘At one point, I thought I would be imprisoned for 13 years,’ says the artist, who has since remade his symbol of oppression in wood, stainless steel and Venetian glass. In a similar vein, the show includes handcuffs in hardwood and in jade, a material with great historical and spiritual significance in China.

Marble Takeout Box (2015), which questions the lasting environmental impact of disposable objects

Within the same display case, visitors will encounter other everyday motifs refashioned in noble materials. A Styrofoam takeout box, remade in white marble, calls our attention to the environmental impact of disposable objects and the dark side of China’s economic development, while a construction helmet cast in glass suggests the fragility of labour protections in an economy built on the backs of migrant workers. While the material shifts prompt us to look at the objects in a new light, the choice of mundane typologies nods to another of Ai’s artistic heroes, Andy Warhol, who taught him that ‘what we do every day has profound meaning’.

The plight of the dispossessed is a recurring theme for Ai, who bemoans that, in spite of economic and technological progress, humans ‘remain a species with no compassion, selfish and short-sighted’. In 2008, he was spurred to action by a magnitude 7.9 earthquake in Sichuan province. It killed at least 69,000 people, many of them schoolchildren, whose schools collapsed due to shoddy construction to which corrupt government officials had turned a blind eye. Ai channelled his despair into a citizens’ investigation published on his blog, and began to use backpacks and steel rebar as motifs for his artwork. On view at the Design Museum will be two calls for remembrance – Snake Ceiling (2008), a 16m-long serpentine installation made of backpacks, and Rebar and Case (2014), which sees three pieces of mangled rebar remade in marble and entombed in wood.

The dumpster-shaped Cabinet (2014)

A wooden cabinet, also made in 2014, was inspired by a different tragedy. In 2012, five boys were found dead in a dumpster bin in Guizhou province. They are believed to have lit a charcoal fire in the bin to keep warm and been poisoned by carbon monoxide. The piece ‘is like a Ming-style classic cabinet, made with the finest materials by the best craftspeople. There are no nails, just hidden joints.’ But by modelling its form after the dumpster bin, Ai is also making a powerful political statement about the people who are left behind while China becomes more prosperous. ‘It comes from my understanding of “it could have been my life”,’ he explains. A similar logic has inspired the more recent installations in the show, comprising life vests collected from the Greek island of Lesbos, bringing to light the global refugee crisis.

Glass Helmet (2022), a symbol of the plight of migrant construction workers

Alongside Ai’s sculptural and design output, there’s documentation of Beijing’s rapidly evolving built environment in the early 2000s, when the government eagerly knocked down older buildings and replaced them with looming towers. Four films take the viewer on a journey across the city’s main streets, while a photo series, National Stadium (2005-7), shows the construction of the Bird’s Nest stadium ahead of the 2008 Summer Olympics. Ai worked with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron on its design, but later dissociated himself from the project and boycotted the opening ceremony. ‘I realised that architecture is political. It doesn’t matter how good the building is, still, after we’ve designed it, it becomes an element of state propaganda,’ he says. In the 15 years since, we’ve seen more flagrant instances of sportswashing – among them last year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing and World Cup in Qatar. With this in mind, does Ai still believe that his disavowal of the stadium was worth the personal cost he has endured?

‘Very often, speaking up is not going to work, because the powers you’re against are so massive. And whether the Olympics or the World Cup, it’s really about profit. You have to remember this one line in the movie All The President’s Men: “Just follow the money”. Then you can understand most political intentions,’ Ai replies. Even so, he insists on taking a stand against misinformation and the loss of human life: ‘You always have to be prepared to speak out, no matter how big the consequences, to protect the most profound meaning of being human.’

A Chinese-style daybed, designed by Ai, in his study, with Self-Portrait in Lego (2017) in its presentation box

That belief in free speech, and in standing up for one’s convictions, informs Ai’s Study of Perspective series. The innocuous title belies the images’ defiant intent: it shows the artist pointing his middle finger at sites of political and cultural power, such as Tiananmen Square and the White House. A selection of these studies will be on view at the Design Museum.

Free speech is likewise the theme of The Animal That Looks Like a Llama But is Really an Alpaca 2023 (2023). Previewed on the limited-edition cover of Wallpaper's April 2023 issue, the colourful pattern is being made into a wallpaper that will wrap around the museum’s atrium. Among its motifs are surveillance cameras, handcuffs, chains, steel rebars, alpacas and Twitter birds. The alpacas are a reference to a Chinese meme that pokes fun at internet censorship, and a testament to humour as a tool against authoritarianism. Meanwhile, the birds reflect Ai’s unwavering faith in the power of social media. He became a household name in China thanks to his blog, which started in 2005 and had 17 million readers in its four-year lifetime, and remains an avid user of Instagram and Twitter today. Though he acknowledges social media’s deleterious effects on individual attention spans and its potential as a vehicle of misinformation, Ai points out that ‘we don’t have another choice. This is the only time in human history which equips us to be individuals. The overflow of information means we can make our own judgments and express ourselves independently.’

At his home in Portugal, Ai is building a replica of his Shanghai studio (torn down by the Chinese authorities in 2011), working with local construction workers and using traditional Chinese techniques

While drawing on specific contemporary concerns, ‘Making Sense’ speaks to universal human themes, says Justin McGuirk, the museum’s chief curator. ‘It takes a step back from the detail of design, and really looks at design as a way of being that hasn’t changed. Weiwei shows us that design is a language that communicates to us across generations, through which we can understand something about our ancestors.’

Ai is measured in his assessment of his own impact. He points out, for instance, that he’s not hopeful he will see a democratic China in his lifetime. This being said, as a believer in cumulative power, he is ultimately optimistic that things can change for the better: ‘My work may just be one drop of water in the ocean, but the ocean is made of water. So I want to remind people, whether in China or the West or elsewhere, that we have to understand one another, and treat one another with compassion. We have to see humanity as one.’

‘Ai Weiwei: Making Sense’ is showing from 7 April – 30 July at Design Museum, 224-238 Kensington High Street, London W8

Ancient olive trees await replanting around Ai’s new studio on his property

Ai’s cats Yellow and Beauty

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.