Pistols at dawn: PTMADDEN’s early encounter with the legendary punks

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

‘If you haven’t guessed already, we’re the Sex Pistols!’ Thus spoke Johnny Rotten, at the Nashville Rooms in West Kensington, on 3 April 1976, before his group blared into their first song: The Who’s decade-old 'Substitute'. (Rotten seemed especially to relish the line ‘Now you dare to look me in the eye…’.) The Pistols had already played to art-school audiences at St Martin's and Chelsea, as well as in semi-derelict studio spaces at Butler’s Wharf. In the spring of 1976, they began a series of gigs at conventional rock venues: the 100 Club, the Marquee and the Nashville, where they supported The 101ers, a pub rock band fronted by Joe Strummer. He would later recall that the Pistols’ skinny young singer had a habit of pulling out a handkerchief and theatrically blowing his nose between songs – a gesture not exactly typical of mid-1970s rock aristocracy.

Among the audience at the Nashville Rooms that night was Paul Terence Madden, an art student from Liverpool then enrolled at the London College of Printing. He’d been to almost all of the Pistols’ early concerts, including their first, at St Martin's, in November the previous year, when they had played for a scant 20 minutes before someone pulled the plug. Late in March, Rotten had stormed off the stage at the 100 Club after trying to start a fight with bassist Glen Matlock. Madden was intent on documenting the band before they split up.

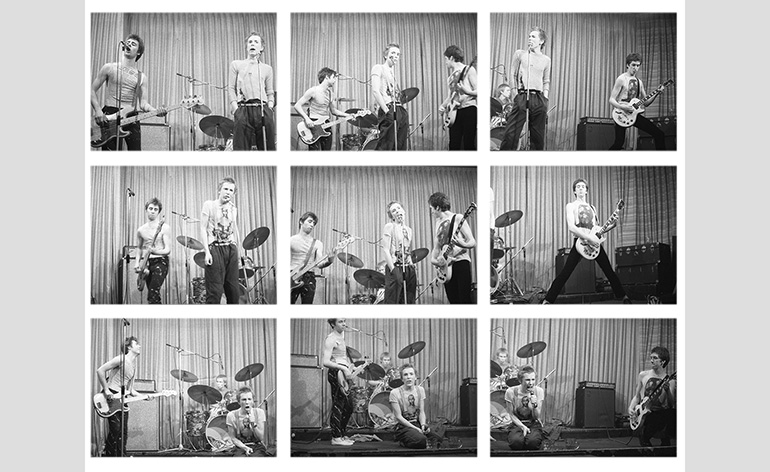

Madden arrived early in West Kensington, politely asked the Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren if he could photograph the concert, and took his place in front of the stage, balancing his borrowed camera on a chair back instead of a tripod. He had three rolls of film, and planned to take a picture every 30 seconds, whatever might be happening, or not, on stage. Twenty-six of those photographs survived, and are about to be exhibited for the first time at a new show, curated by Colin Fallows, professor of sound and visual arts at Liverpool John Moores University, at London’s Wilkinson Gallery.

The photographs look familiar in certain respects – the early days of the Pistols were well documented – but oddly staged compared to the most commonly reproduced images. Thanks to Madden’s stark frontal view, the four band members look like mannequins posed to represent the anthropological category of the rock band. The first striking thing about these images is just how untogether the Pistols seem. Guitarist Steve Jones is in his own world of aspirant rock cliché, throwing shapes from Chuck Berry and Johnny Thunders, but mostly borrowed from Pete Townshend. Matlock, as ever, looks like an eager contender for a Battle of the Bands contest. Only Rotten seems to come from somewhere else entirely, and not just a different group. He looks as though he shouldn’t be in a band at all, despises the category in fact. Hands thrust deep in pockets, brothel creepers planted firmly at the front of the stage, he regards the unseen audience, and occasionally the camera, with the mordant stare that will soon become his trademark. It’s hard to know how much is real and how much is rehearsed. Strummer and others recall McLaren coaching his ostensibly anarchic charges, telling them where to stand and when. Fallows calls these images ‘a photographic document of a group of young artists in the momentary process of “becoming’’.’

Something in the photographer’s method means the awkwardness of the Pistols’ artifice is all the more evident, untrammelled by the usual cartoonish nostalgia that attends the history of punk, and which is especially prevalent in an anniversary year like this one. In 1976, the young artist, who nowadays goes by the name of PTMADDEN, had lately been exposed to artist Ed Ruscha’s laconic Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) and to the architectural typologies of photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. Hence the arbitrary but enlightening decision to take just one photograph every 30 seconds; the artwork was the series, not any individual image. What PTMADDEN has now chosen to exhibit is a typology of a Sex Pistols performance: a collection of poses made significant only by the action of the camera shutter. The effect is to turn one of the most familiar – perhaps over-familiar – moments in 20th-century British culture into something else, an era subtly estranged. Consider how familiar the iconography and the texture of punk now appear: the well-syndicated gobbets of concert footage in which you can spot members of the Pistols milieu working themselves up and sharpening their wings for their own Icarus flare-ups of fame. Here is Siouxsie Sioux just offstage, in suburban Night Porter chic. A fleeting pogo-blur in the crowd: unmistakably Shane McGowan. The fragile figure of Sid Vicious, waiting his turn as bassist (of sorts) once Matlock has been ousted. And, at the centre of it all, the oddly reassuring face of Johnny Rotten, who in retrospect has ‘national treasure’ written all over him, and seems as limited and reliable a source of controversy and quotes as sundry 1970s contemporaries such as George Best, Oliver Reed and Quentin Crisp.

But, of course, he was nothing of the kind; not yet, not in the spring of 1976. It wasn’t until the summer that the Sex Pistols began to seem like a threat, like the future, like a commercial concern. In the autumn they played the 100 Club again and a girl was glassed and partially blinded; the band’s notoriety was assured, and all that followed. But first, the quartet that PTMADDEN framed with his camera had to be transformed into an underground myth. On 23 April, the Sex Pistols played the Nashville for a second time, again supporting Strummer’s band. This was the gig everyone came to: Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, Tony James, Keith Levene. This was the gig where Vivienne Westwood got ‘bored’ and hit a girl in the crowd. The ensuing melée, which ended the concert, was photographed by Joe Stevens. All the principals, Rotten and McLaren among them, may be seen weighing in, and they all look already like cartoon punks, flailing clichés.

PTMADDEN shows us something else. The serial austerity of these photographs, the way they freeze the group at arbitrary instants – photographically, the opposite of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’ – means they end up, even blurry personalities like Jones and Matlock, looking as if they’ve paused for thought, wondering what this adventure might hold next. At one point Rotten kneels on stage, bent over his microphone, in the same attitude he’d be found two years later at the Winterland Ballroom, San Francisco: the final Sex Pistols concert. On that occasion, as the group was about to implode, he’d ask half mockingly and half despairingly: ‘Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?’ In the meantime, in most of PTMADDEN’s 26 photographs, he’s just begun to figure out who or what ‘Johnny Rotten’ might be.

As originally featured in the May 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*206)

INFORMATION

‘Sex Pistols, April 1976: The Art of PTMADDEN’ is on view from 15 April – 15 May. For more information, visit the Wilkinson Gallery's website

Photography: PTMADDEN

ADDRESS

Wilkinson Gallery

Vyner Street

London E2 9DQ

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.