Red lines: David King’s stockpile of Soviet design agitates again at Tate Modern

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As art editor of The Sunday Times Magazine between 1965 and 1975, David King helped revolutionise magazine design in the UK and beyond. Working with art director Michael Rand, King brought a new visual punch to the country’s first Sunday supplement, just three years old when he arrived, using bold sans serif type and tightly cropped photography, and putting together photo stories with cinematic sweep.

On the side, King also designed the covers for The Who Sell Out and Jimi Hendrix’s Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland and photographed Muhammad Ali training for the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ bout with George Foreman (King took up editorial photography, using a Nikon F2, after four hours of instruction from Don McCullin). He also came up with a logo for the Anti-Nazi League, designed the covers for City Limits, a leftist rival to London’s Time Out guide, long departed, and later worked with Bruce Chatwin on Photographs and Notebooks.

Installation view, ‘Red Star Over Russia: A Revolution in Visual Culture 1905-55’.

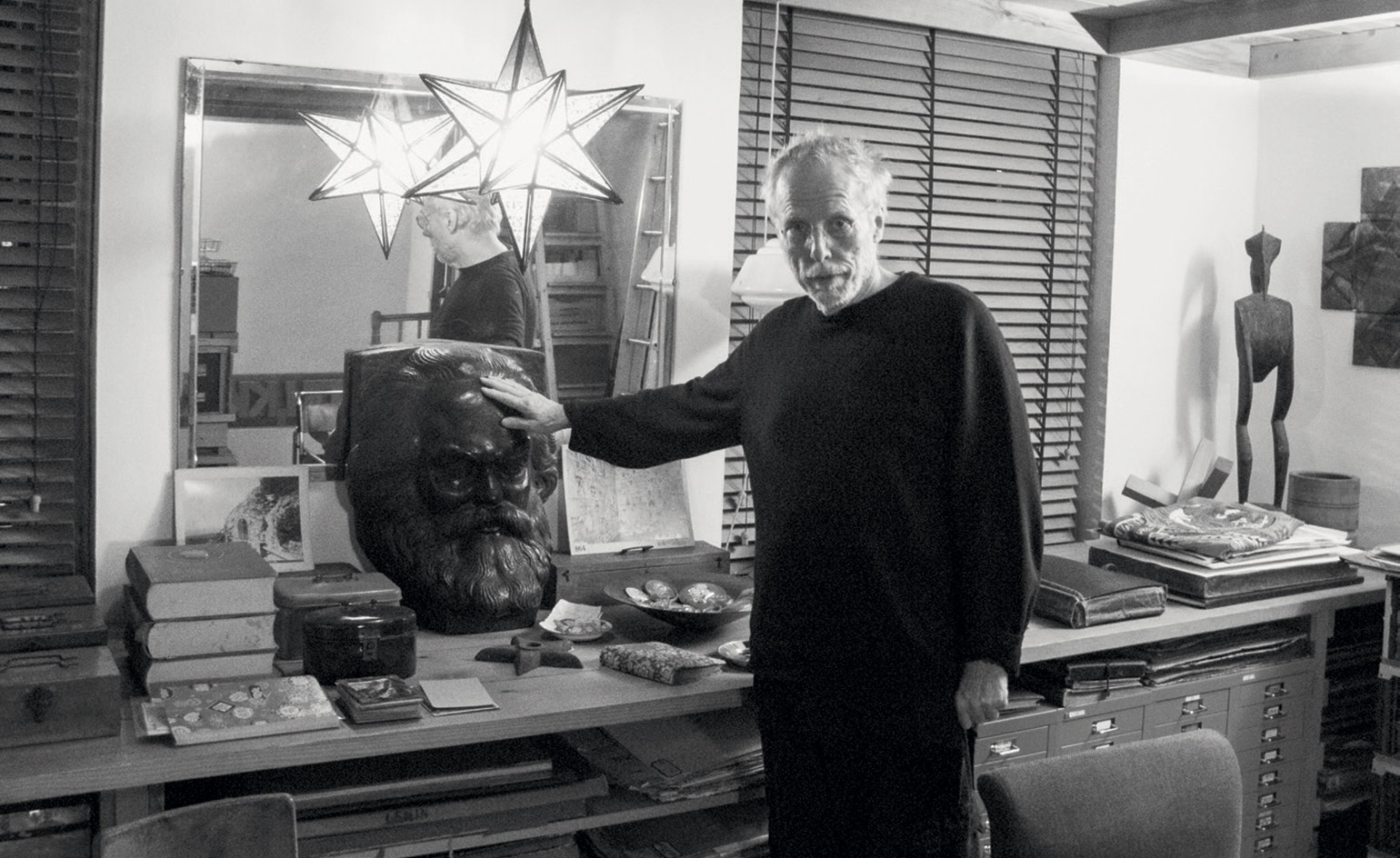

King was also a historian and a serious Russophile, putting together one of the largest collections of Soviet posters, flyers, magazines and photography anywhere and publishing a series of revelatory books on Soviet history and visual culture, and the use and abuse of photography, including The Commissar Vanishes and Red Star Over Russia.

King passed away last year, aged 73, and his collection was bought by Tate. This month, to mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution, Tate Modern is opening ‘Red Star Over Russia: A Revolution in Visual Culture 1905-55’, drawing on just some of King’s 250,000-piece strong Soviet stockpile.

King first visited the Soviet Union in 1970, hunting background material for an article about the centenary of Lenin’s birth. He was already an admirer of Soviet Constructivist design, this before the cult of Aleksandr Rodchenko. (King was in many ways central to the development of that cult. He worked with David Elliott at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford on a groundbreaking Rodchenko show in the late 1970s. The curator of the Tate exhibition, Matthew Gale, says King tired of the associations, though the influence on his work was clear. ‘He went a bit off the boil with Rodchenko,’ Gale says. ‘He thought that Gustav Klutsis was doing things that were even more exciting. But you can see how magazines like The Face came out in the wake of the interest in that period, filtered through things like The Sunday Times Magazine. That is another spiral of history on top of all the others in the exhibition.’) King was also a Trotsky obsessive. He began collecting as much Trotsky-related material as he could then spread out, making contacts in Russia, eastern Europe but also in the US and Mexico and developing a kind of mythology around his detective work. ‘He could spin a good story,’ says Gale, ‘and you think about story and history sometimes.’

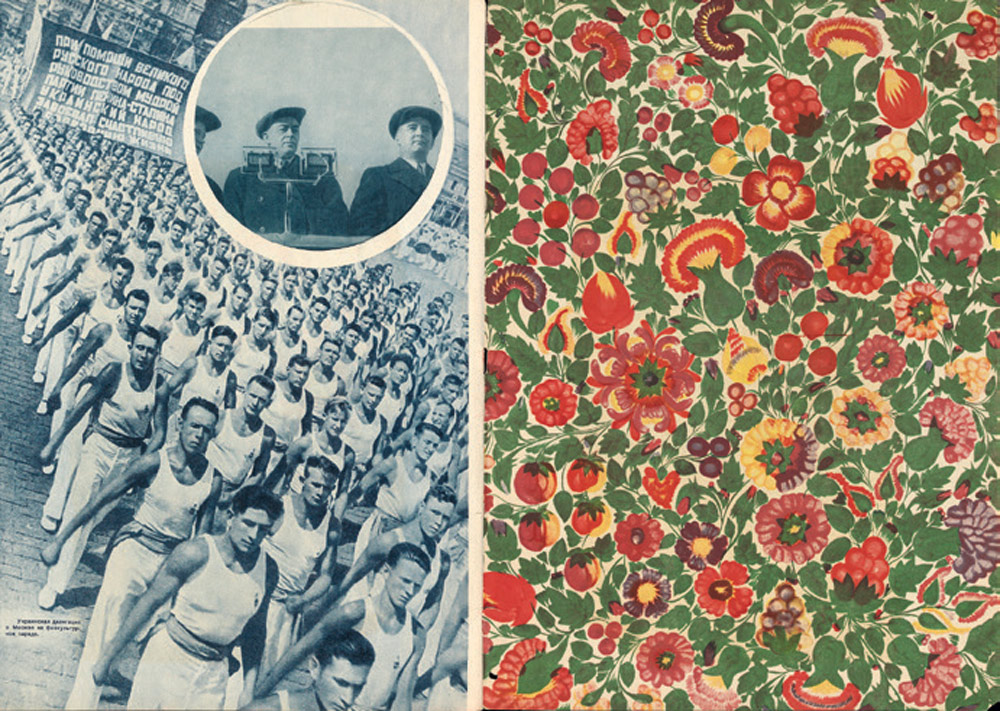

‘USSR in Construction, no. 11-12, 1938’, issue on Kiev, spread designed by Aleksandr Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova

Gale first collaborated with King 15 years ago. He says the importance of the collection is not just its depth and breadth but King’s particular way in. ‘There is something about that single-mindedness and his visual take that make it a particular thing,’ he says. ‘At the beginning, there was a fascination with the rich design culture of the 1920s and 1930s, not just in Russia but also Germany. And that clearly influenced the way he designed things. But he also had that collector’s bug. He needed to get everything. Up until he died, he was still trying to complete collections of obscure Russian magazines.’

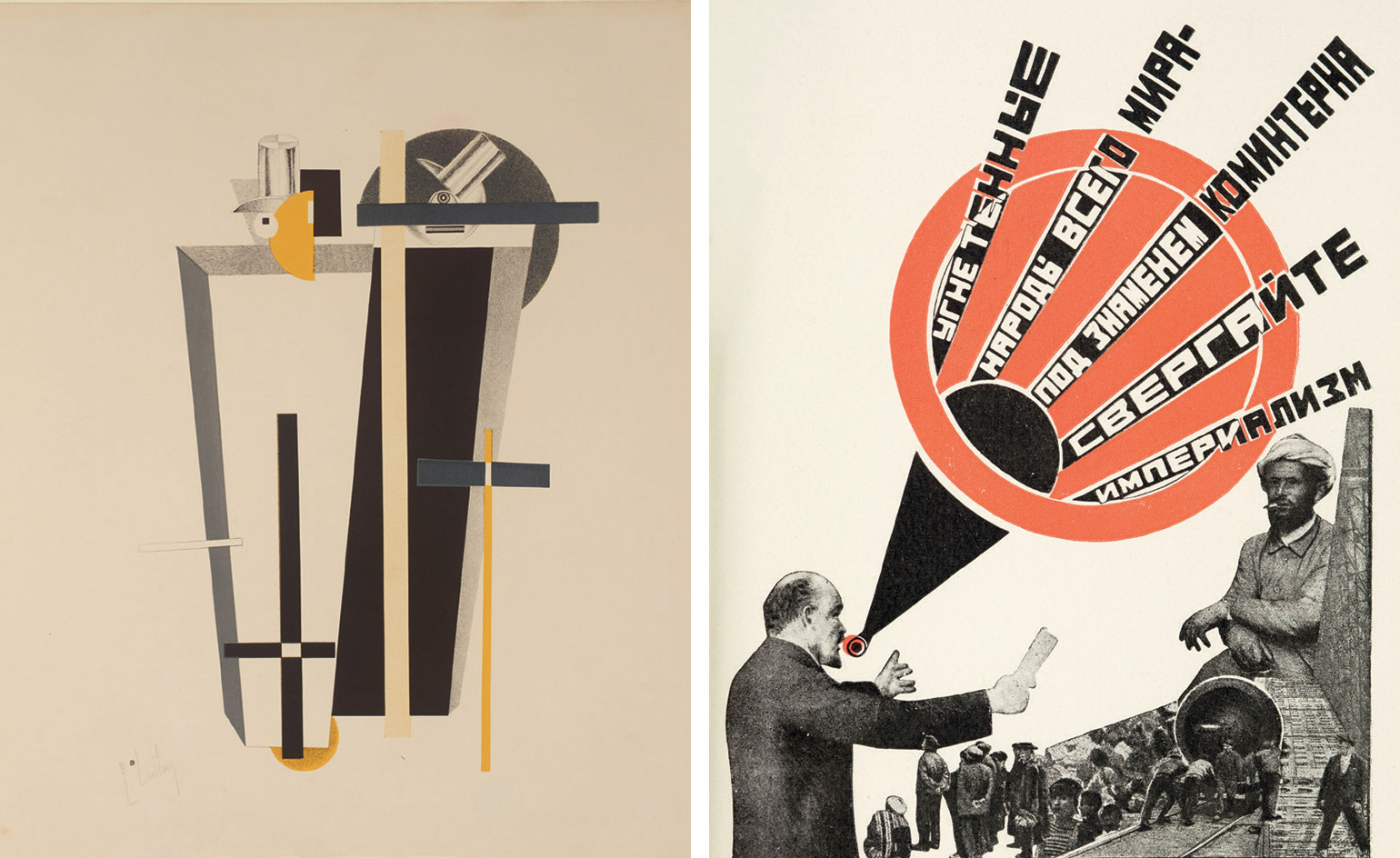

The exhibition pulls in art and design from Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Klutsis and Nina Vatolina. It also covers the Bolshevik ‘agitprop’ trains, mural-splashed travelling PR machines aimed at explaining the goals and means of the new government. And more broadly at how much public art, from propaganda posters to monumental sculptures to street performance, was a feature of Soviet life in its first optimistic flush. But it also looks at its souring and the terrors of Stalinisation. There are stark mug shots of those dragged to the Moscow show trials and off to the Gulags or the gallows.

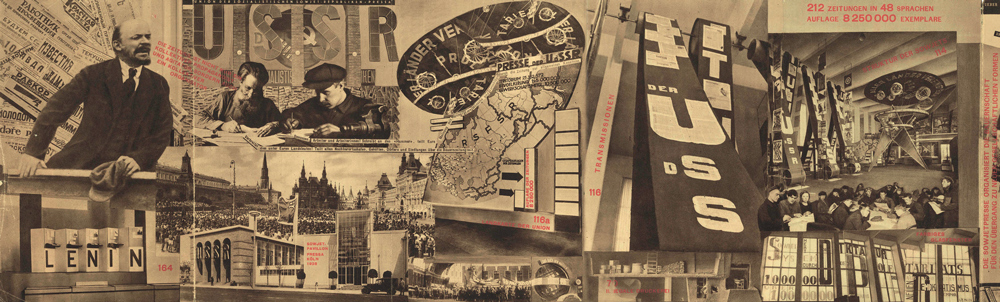

‘The Task of the Press is the Education of the Masses’, photomontage from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: Catalogue of the Soviet Pavilion at the International Press Exhibition, Cologne 1928, by El Lissitzky and Sergei Senkin

As Gale says, in some ways the exhibition is also about the particular power of paper, print and effective design; of posters, pamphlets, magazines and flyers to, as the saying went, ‘educate, agitate, organise’. It is a power hard to imagine now. And these are traces easily lost, forgotten or denied. ‘It is vulnerable material – because people just throw it out or because others actively want to suppress it. This is exactly what King was hoarding. He has some flyers that were thrown out of the back of the lorries at the moment of the revolution. These are not things that readily survive.’ The show is also about photography, its unique charge and abuse in a repressive state. And again there are resonances to pick up on. ‘Some of King’s work was about people being photoshopped out of history and that is so easily done now. Does that mean we are able to wipe people from history?’

Gale admits that there are losses and gains in moving King’s collection from a domestic to an institutional setting. ‘His house was an extraordinary place. And if you went to visit him and he thought of something he wanted to show you, he could just pull it out and tell you what page it was on. Part of the impact of his death, apart from the personal one, was this sudden vacuum of knowledge. The collection has morphed into this thing that has an institutional apparatus, going from warm to cold I suppose. But we have this amazing public resource now, something we can keep revisiting.’

As originally featured in the November 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*224)

Left, Gravediggers (Totengräber), lithograph on paper, by El Lissitzky, 1923. Right, illustration for Young Guard, no. 2-3, by Gustav Klutsis, 1924

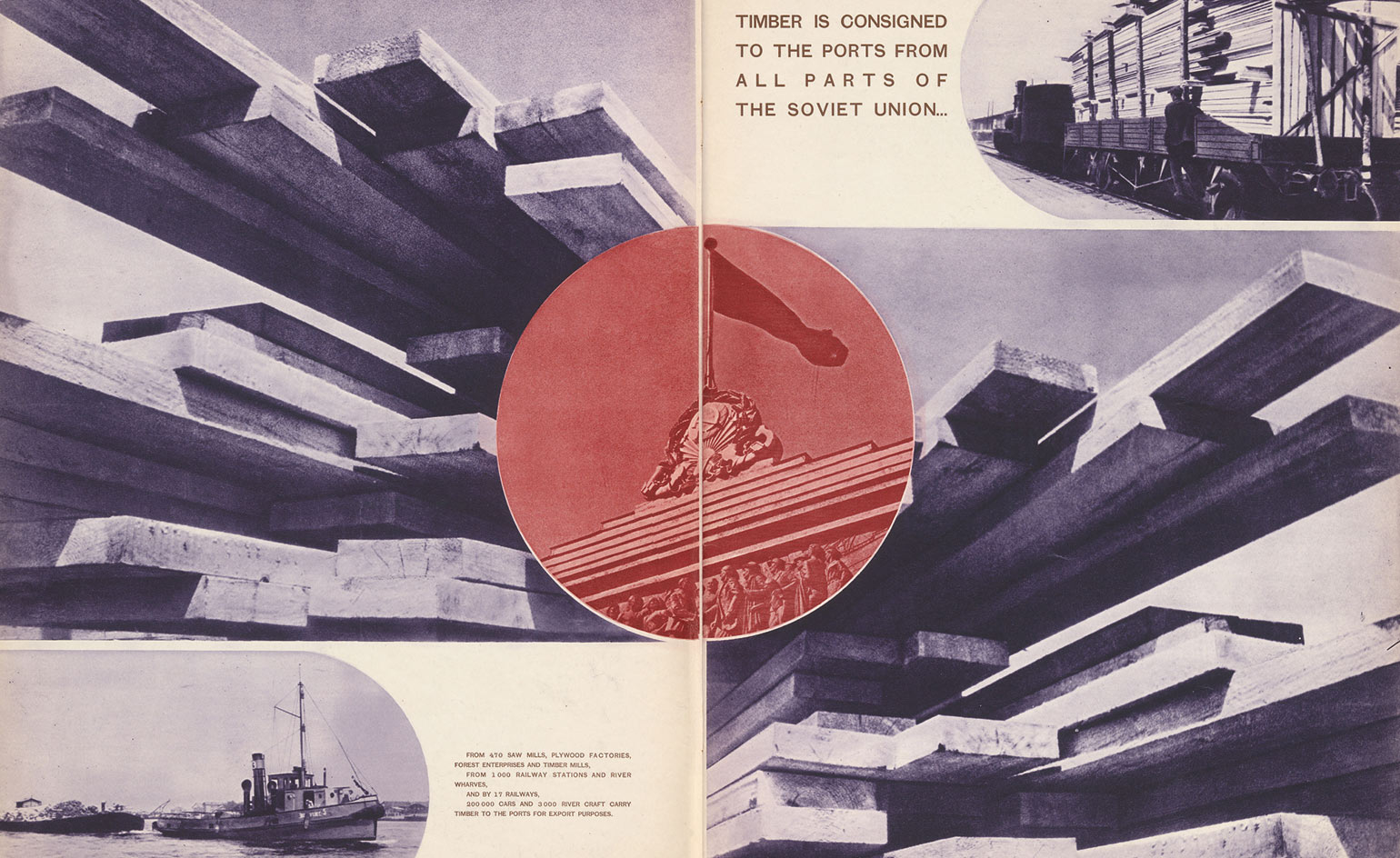

USSR in Construction, no. 8, spread designed by Aleksandr Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, 1936

INFORMATION

‘Red Star Over Russia: a Revolution in Visual Culture 1905-55’ is on view until 18 February 2018. For more information, visit the Tate Modern website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG