Ralph Steadman has worked with everyone from Hunter S. Thompson to Travis Scott and Quavo – now, the Gonzo illustrator is celebrated in London

A new exhibition provides a rare opportunity to experience the inimitable work and creativity of Gonzo illustrator Ralph Steadman up close. Just don’t call it a ‘style’.

Standing before the sprawling prints and etchings at the Muse Gallery on London’s Portobello Road, it’s easy to forget the digital reproductions, magazine print runs and iconic book covers that first introduced many of us to Ralph Steadman’s anarchic line work. It’s the way that most will have seen it, but it’s only when faced with an original or full-size print that one begins to truly appreciate their scale.

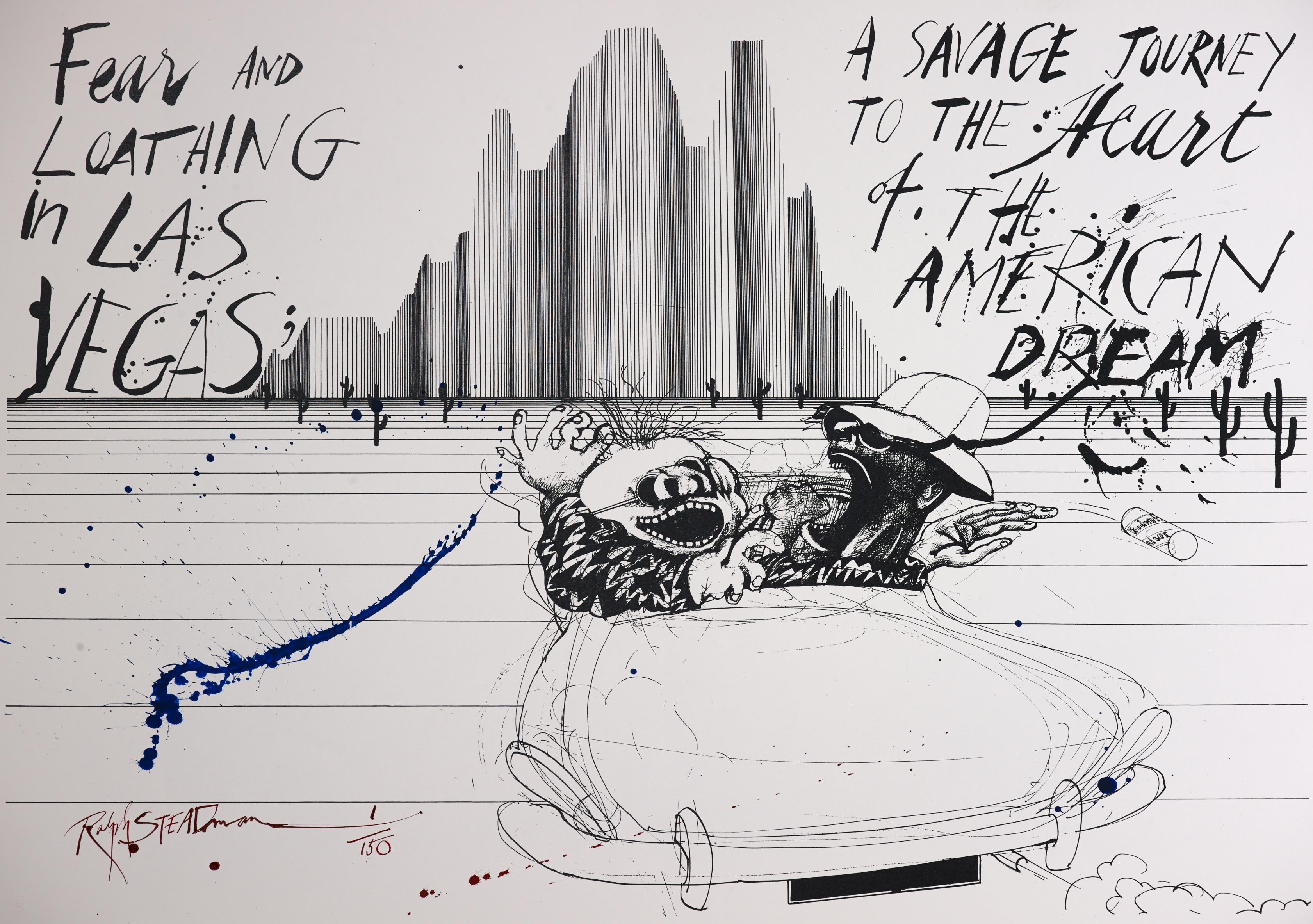

'Once Upon a Line,' which runs until September 21, showcases a powerful and often unseen selection of fifteen limited edition prints, etchings and sculptures from Steadman’s seven-decade career, including rare pieces never before exhibited in London. It also coincides with the 30th Anniversary of the Portobello Film Festival, to which Steadman contributed this year’s official poster artwork, ‘If I want it to be a sky, it's a sky’.

Ralph Steadman

'The first day, it’s rather exciting and then it suddenly gets boring,' Steadman states playfully, reflecting on the act of exhibiting his work. His daughter, Sadie Williams, who has spent the last two decades overseeing his artistic legacy as managing director of the Ralph Steadman Art Collection, laughs, noting his playful mood before interjecting.

'You’ve hit the pin on the head saying that you've only ever experienced dad's work in digital, magazines or books,' she adds. 'Standing in front of an original or even a print, suddenly you get a sense of the size of some of the works, because a lot of what works on is A1. I think that is a different experience for people.'

His works started off small. Learning his craft from a mail-order drawing course after dropping out of school in the early 1950s, he later contributed political cartoons to a number of newspapers, as well as the one-panel cartoon ‘Teeny’ for a local paper – all of which Williams characterises as 'very un-Steadman'.

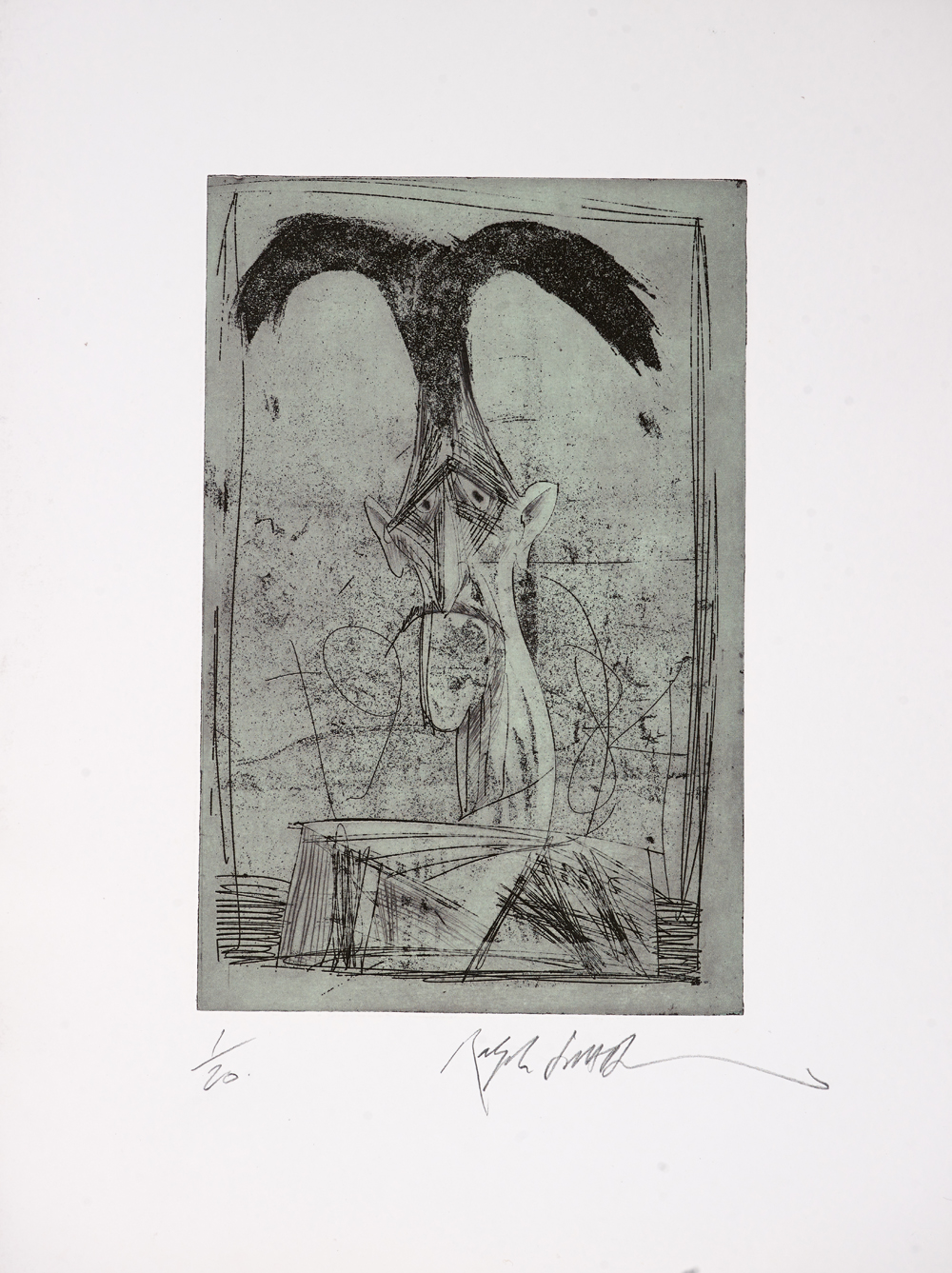

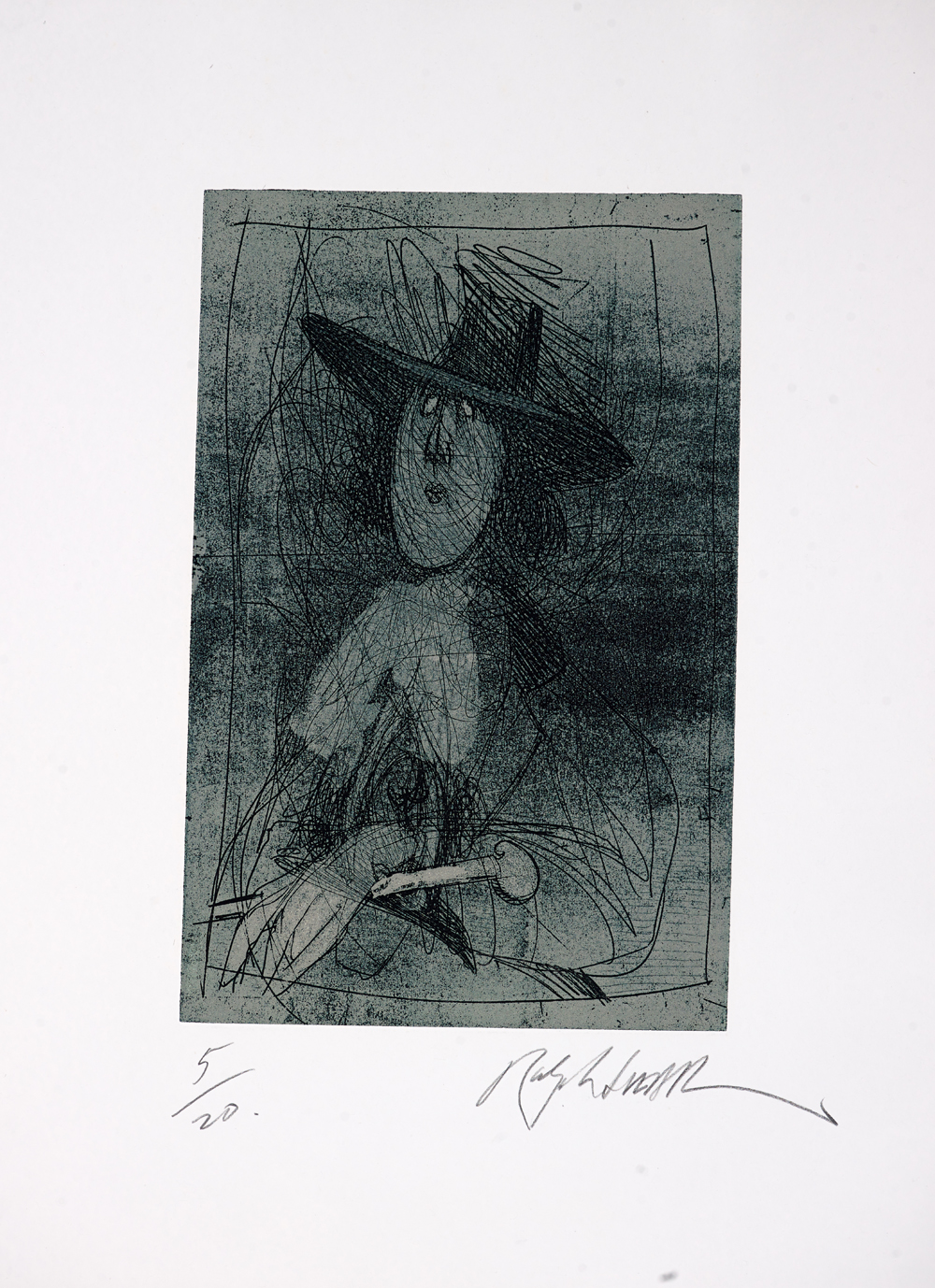

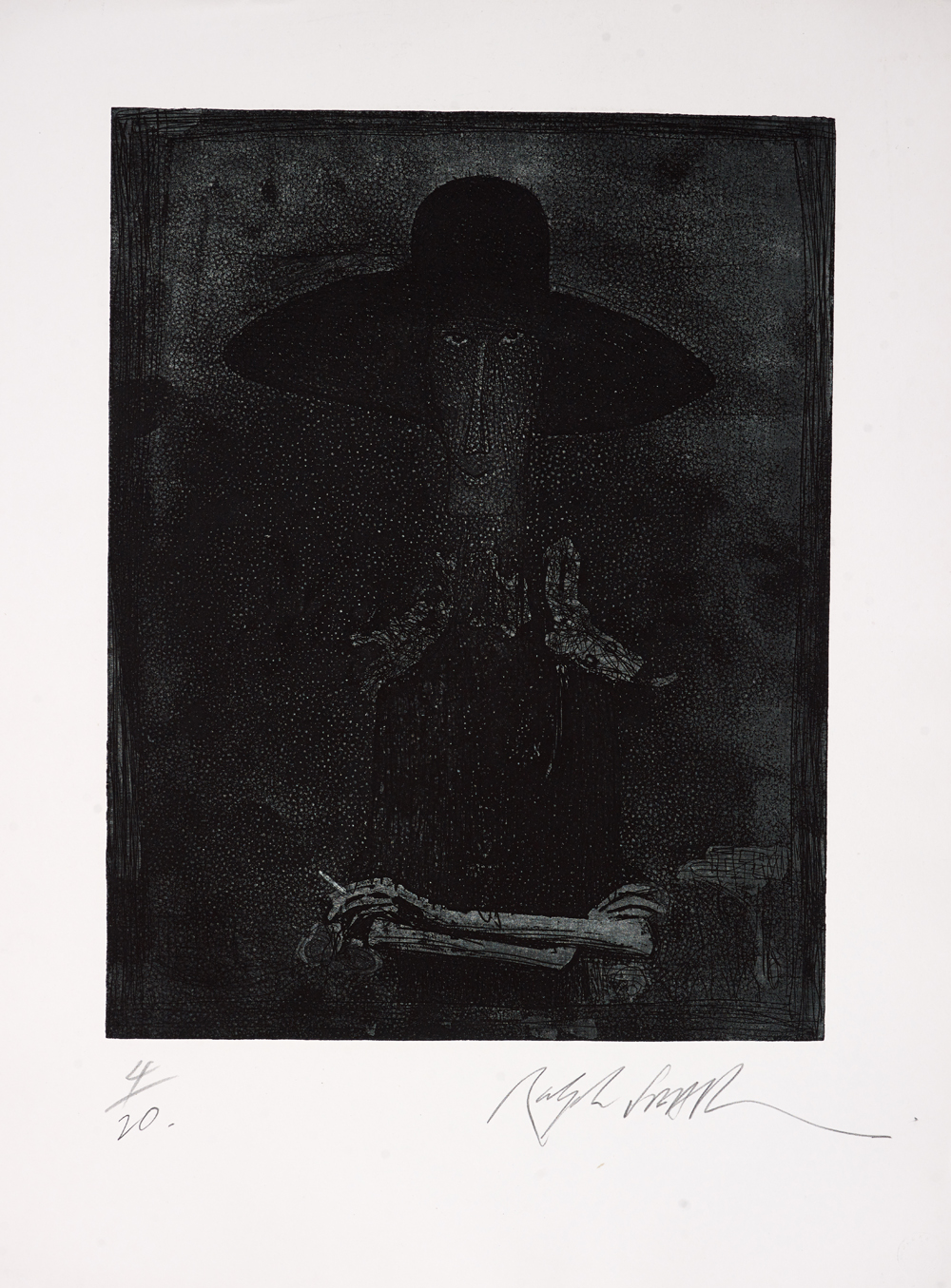

In contrast, the 15 pieces on display at the Muse Gallery span the breadth of Steadman’s interests in different approaches that encompass six centuries of processes, from block printing and etching to silk-screen and digital. Whether it’s Steadman’s towering triptych screen print interpretation of Picasso’s Guernica, or his etchings of George Orwell, Oscar Wilde and William Shakespeare, every medium presents an opportunity to push boundaries, either through a newly discovered method or a scrap of paper.

'I always say with the greatest of respect now that anything in dad's hands can be the opportunity for creativity, Williams notes as Steadman playfully attempts to debunk her point by holding up a used tissue. 'And now he's proven me completely wrong.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Steadman's portrait of George Orwell

More recently, Steadman has explored 3D imaging alongside Charlie Baird, creative director of Fluorescent Smogg, an editions house specialising in fine art editions. The result was a sculptural rendition of the classic Hunter S. Thompson portrait, Gonzo Guilt! in cold cast bronze, which appears at the Muse Gallery alongside the original work. It follows several years of collaboration between the duo, with Fluorescent Smogg being instrumental in bringing many of these unseen works to the Muse Gallery.

'It’s a great charitable venture,' enthuses Baird. 'They take a lesser percentage of normal galleries and, of course, the Portobello Film Festival is a free festival. And it was really interesting to see something turned from 2D to 3D and run it by Ralph and have him say what he likes, what he disliked and make it honest to the piece, which I feel like it ended up being.'

Baird cites one particular piece in the exhibition as a bridge, of sorts, between Steadman’s world of ink splatters to the rebellious punk spirit of street art: ‘Something New Has Been Added’, a screenprint riddled with bullet holes – the result of a decision to take prints to the home of author William S. Burroughs, where they were subsequently shot at by Burroughs, Steadman and his wife Anna with pump action shotguns.

Screenprint ‘Something New Has Been Added’

'What I find inspiring, being from graffiti, is you have this kind of rebellious attitude,' Baird observes. 'No laws have really been broken in any of this, but it has that kind of punk energy that really goes to the side of where I’m from. I'm just like, ‘How have I not thought about that?’ To shoot a fucking print? That's how you hand-finish a print, Banksy.'

Steadman has always been fond of using art to say the unsayable, or at least articulating it in a way that words perhaps couldn’t. This drive to communicate is evident throughout Steadman’s body of work – his grotesque caricatures of despised public figures, often created for political publications, offer both satire and catharsis – or his version of it, at least.

'I’m burning them, really,' he states with glee. 'I need to sort of crucify someone every day, you know?'

'It's not like he's trying to be secretive about it, like an abstract painting,' Williams clarifies. 'He very deliberately wants to convey a certain message, or point of view. It's about communication through visual sort of stimulus. There's a very clear message in a lot of what he says and does.'

There’s a playfulness in their naming conventions too, with Steadman often favouring the use of puns as titles for his work. He even came up with the name for the exhibition itself. Ever the great note taker, these often prove particularly useful to Williams when it comes to cataloguing his work.

'It's quite helpful actually, especially with things like the Critical Critters pieces,' she notes, reflecting on his collaborative work with conservationist and filmmaker Ceri Levy that has resulted in a series of books focused on environmental issues. 'There's often a little note on the bottom, which makes it quite easy for us as archivists who are working through thousands of pieces in the archive to actually title stuff… So you go, ‘Oh, that's the title. Great. Phew.’'

Steadman's portrait of Oscar Wilde

Steadman’s love of the written word was a cause of resentment, of sorts, between himself and perhaps his closest collaborator, the enigmatic counter-culture journalist and writer Hunter S. Thompson. Renowned for his timeless Gonzo works, they remain almost impossible to imagine without their anarchic illustrations, although Williams posits that Thompson’s attitude may well have been coloured by the fact that Steadman could write better than he could draw, to which he agrees.

'Of all the people I met in America, it had to be Hunter Thompson,' Steadman states ruefully. 'I didn't know I was going to meet him. I was told ‘Somebody will meet you at the Kentucky Derby’ and it was him.'

Steadman first accompanied Thompson in 1970 to illustrate a piece for Scanlan's Monthly magazine when original artist Pat Oliphant was unable to attend. The resulting article ‘The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved’ paved the way for some of Steadman’s most recognisable works, including ‘Savage Journey’, which also appears at the Muse Gallery, having adorned the pages of Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, both in its Rolling Stone serialisation and the book itself.

'I was crucified by Hunter Thompson, wasn't I? It was terrible being ‘Ralph,’' he says, imitating Thompson’s pointed, withering Kentuckian diction. “He’d always say ‘I’d feel really trapped in this life if I didn't know I could commit suicide any moment’. Which he did, of course.'

Thompson’s suicide in 2005 had a profound effect on Steadman, with whom he had collaborated for over three decades. There was, as Steadman concedes, a tragic inevitability to it. On one occasion, Williams recalls her father being invited to join Thompson on a visit to a funeral home.

'I think he just wanted it to be an event people would go to, you know, because he was about to be crucified,' Steadman states bluntly. 'He was a suicidal twit, to end up doing something like that. And he wanted to, you know? He wanted to be Jesus Christ, really. He'd like to be looked upon as somebody like that. And, I mean, from Kentucky of all places.'

Even commissions, traditionally viewed as a constraint for many artists, have continued to provide fertile ground for Steadman to experiment. In 2014, he was enlisted by Sony Pictures to create a series of character illustrations for a limited run of Breaking Bad Blu-ray box sets at the request of series creator Vince Gilligan. The request demanded a crash course through the series in just three weeks, yet Steadman transformed scraps of paper into Albuquerque landscapes with effortless flair – although there was one image that never saw the light of day.

'He did Skyler White, but she didn't approve it,' Williams explains, recalling actor Anna Gunn’s reaction to Steadman’s interpretation of her character. 'She had image approval and she didn't like it so it's all the male characters on the box set. Skyler is just sitting in a drawer, never to be seen.'

Steadman’s collaborations have also spanned generational and cultural divides. From more recent work for musicians Travis Scott and Quavo on their album Huncho Jack, Jack Huncho, to the unforgettable poster artwork that defined Bruce Robinson’s cult classic semi-autobiographical comedy Withnail & I he is always intrigued by prospect of being surprised by a potential collaborator.

'It’s what someone might ask me, which is unexpected,' he states with excitement. 'That’s the best part, isn’t it? Something like, ‘What colour’s your underpants?’ Completely unexpected. It’s got to be that. Not, ‘Oh, I know what he'll ask’. And they do.'

Portrait of Virginia Woolf

For all the notoriety of Steadman’s Gonzo partnerships and high-profile commissions, his roots remain firmly in the tactile, observational world of his youth. He fondly recalls his art teacher Leslie Richardson, describing him as 'the most interesting man that I ever met.' It was under his tutelage that Steadman learned that 'anything is possible.'

'That was the best thing I ever stuck to – doing drawing with him,' he recalls of his decision to enroll at East Ham Technical College in 1959, having been frustrated by the limits of his skills. 'It was wonderful to go and spend days at the Victorian Art Museum or the Natural History Museum, and just go there and sort of be given a reason to do things. It was interesting.'

One thing that’s abundantly clear from viewing a mere snapshot of Steadman’s work up close is that his life and work cannot be neatly packaged – nor should they be. Standing in front of his prints at the Muse Gallery, his illustrations feel like an irresistible invitation to step closer, look closer and perhaps even laugh in the face of the inevitable messiness of life. But whatever you do, just don’t refer to his aesthetic as a 'style'.

'I always cringe when someone asks about his style,' Williams states. 'I'm like, ‘Oh, here it comes.'

'It’s not a style,' he clarifies. 'I hate style. Content – that's what I put in. I’ve never liked the idea of having to get a ‘style’, you know?'

With that in mind, long may Ralph Steadman’s 'content' endure.

Ralph Steadman at Muse Gallery until 21 September