Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s multiplayer experience at London’s Serpentine invites visitors to connect in the real world

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley rethinks a typical art gallery visit with a new exhibition at Serpentine which encourages viewers to get off the screen

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Traditionally, art galleries can be solitary experiences, with visitors avoiding eye contact on a stroll around an exhibition. It is a custom Berlin-based British artist and game designer Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is keen to challenge, with the artist’s immersive new exhibition at The Serpentine encouraging visitors to interact – with each other.

The video game commission, The Delusion, is a multiplayer experience, inviting viewers to virtually enter digital portals. Inside each one there are conversation starters, reflecting on both the digital world and its often vitriolic and dangerous real-life consequences. Players follow prompts, and are encouraged to engage in honest conversations with themselves and each other.

For Brathwaite-Shirley, the game is a place for players to consider emotions which may spring from virtual interactions, shifting the focus from the digital to the real world in a bid to take viewers off screen. ‘I knew audience participation would be key when I started,’ Brathwaite-Shirley says. ‘Essentially, the aim of the games is to get the audience members to open up to each other - it will be a success if you turn to a stranger that you'd never usually talk to and speak to them. There's lots of different kinds of interaction that try and help build you to this talking moment.’

Websiteflat6, 2025

Brathwaite-Shirley is guided by instinct when creating the work, starting from a feeling – happiness, joy, sadness – and making a world from that, without being sure where it will lead or how it will connect. The end result is an organic mix of memory, experience and fiction. ‘The first time I worked like this, I just thought - what is this? But as feelings from different days are added on, you suddenly start getting a cohesive essence of something. It feels a lot like collage or painting. You are moving things around so that the image appears for you, rather than knowing exactly what it is prior to putting it out. I don’t know what the scene is going to be until it starts telling me.’

What I love about the medium of games is you have to engage with it for it to start, and what you do could mess up the experience for yourself. It’s an investment of time. It feels like a really good medium for a moment of self-reflection

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

The artist is keen to create a space where people can speak freely, away from the often charged atmosphere online. ‘With trust building exercises, the game encourages a slow opening up, building to a gallery-wide conversation. It is set to a backdrop of a fictional world where every comment online comes true all at once, regardless of how crazy it is. It causes havoc and makes people withdraw from the world. In the game, the only way to, connect with people is to imbue physical objects with a magic which allows you to enter portals of the subconscious - something that we all share. When you go into the gallery, it's like going into a house, but instead of behind a door, you might find a portal to another world, something to interact with.’

Websiteflat2, 2025

Animation as a medium has always fascinated Brathwaite-Shirley, who graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art in 2019, before teaching herself how to make video games with 3D editing and game engines (the software framework designed for video game development). In a uniting of disciplines, Brathwaite-Shirley here works with collaborators from the Black Trans and Queer communities across disparate elements of the game, from the controllers and soundtrack to the set design.

‘In the early days, I had this idea that the work reacts for you, rather than just you reacting to the work,’ Brathwaite-Shirley says. ‘It's more of a dialogue. And I think that's why the games have started to become more particular, and why I use less gaming language around them, because for me it's more like I am building a conversation with the work.’ She saw a lot of art, and spent time around many artists who, she says, were more like journalists in the intense research they conducted. ‘The way people then take it in is very consumer,’ Brathwaite-Shirley adds. ‘It's very much like they suck it in and they spit it out in whichever way they want to. What I loved about the medium of games is you have to engage with it for it to start, and what you do could mess up the experience for yourself, and the only person to blame is you. It's an investment of time. In terms of making a mirror, it feels like a really good medium for a moment of self-reflection, and to then see what it could do in an art context.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

An inspiration wall in the artist’s studio

For the artist, it is key above all to form real-life connections off the screen. ‘There's moments where the game shuts off, so you don't have a choice but to look at other people or other things,’ Brathwaite-Shirley adds. ‘Something I was seeing a lot in gaming exhibitions was this beautiful game about humanity and empathy, and no one would look at each other ever, just at the massive LED screen in front of them. We're trying to see if we can use that very strong attention to this screen and then instantly switch it off. It is one big experiment to see if this interactive game can moderate the space, as well as if the people themselves can open up and help other people to as well, to be there and listen for others.’ The nature of the game meant the artist had to relinquish a certain measure of control, handing over the reins of the game’s direction to the players. ‘If the players invested a nugget - putting in their name, religion, gender - then the game gives something back.’

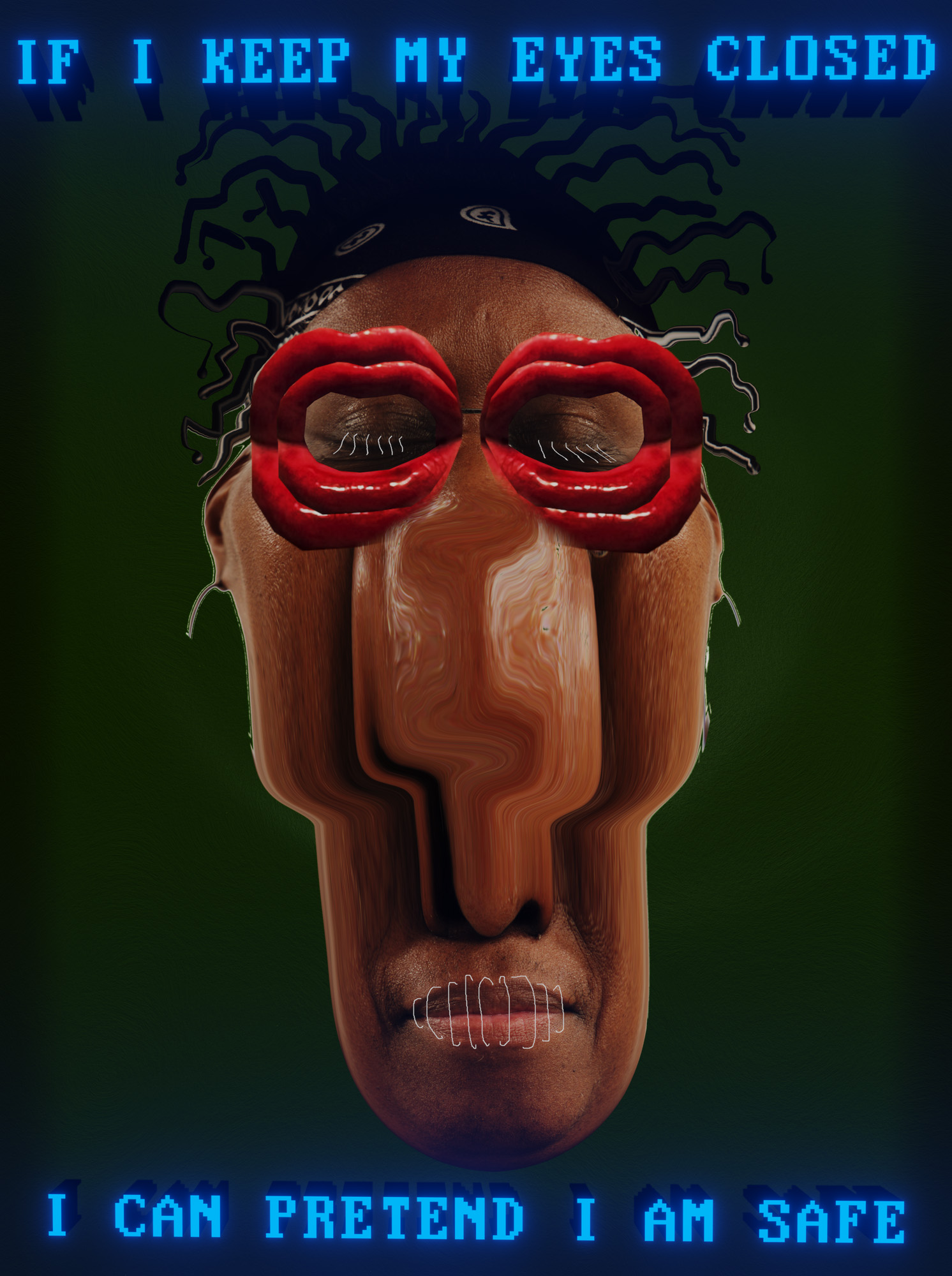

Uncomfortable Honesty, 2024

It is an experiment supported by The Serpentine, who were on hand to advise on the logistics of stepping away from the usual exhibition format, advising on everything from encouraging interaction between visitors to safeguarding and protecting the privacy of players. ‘They really understood that this is an experiment that we want to do. We're aiming for it to be as strong as we can get it, and if we do see that failure, it will be as positive as if we see the success.’

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, The Delusion, at Serpentine North from 30 September 2025 - 18 January 2026

This article appears in the November 2025 Art Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News + on 9 October. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.