The trailblazing women of Bauhaus

The remarkable female artists at the heart of Bauhaus overcame the societal expectations of their time to become pioneers in their own right

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

What makes a true Bauhaus girl? Contemporary, cheerful and cool, she has a self-confident, gung-ho attitude, a short bob, and a talent for the fine and applied arts. Or at least, that’s according to a groundbreaking three-page spread, published by Die Woche newspaper in January 1930 in a politically turbulent Germany. The article is illustrated with photographs of these newly emancipated Bauhaus women taken by ‘Lutz Feininger’ – 19-year-old T Lux Feininger, and the youngest son of German-American painter Lyonel Feininger, master printmaker at the Bauhaus school.

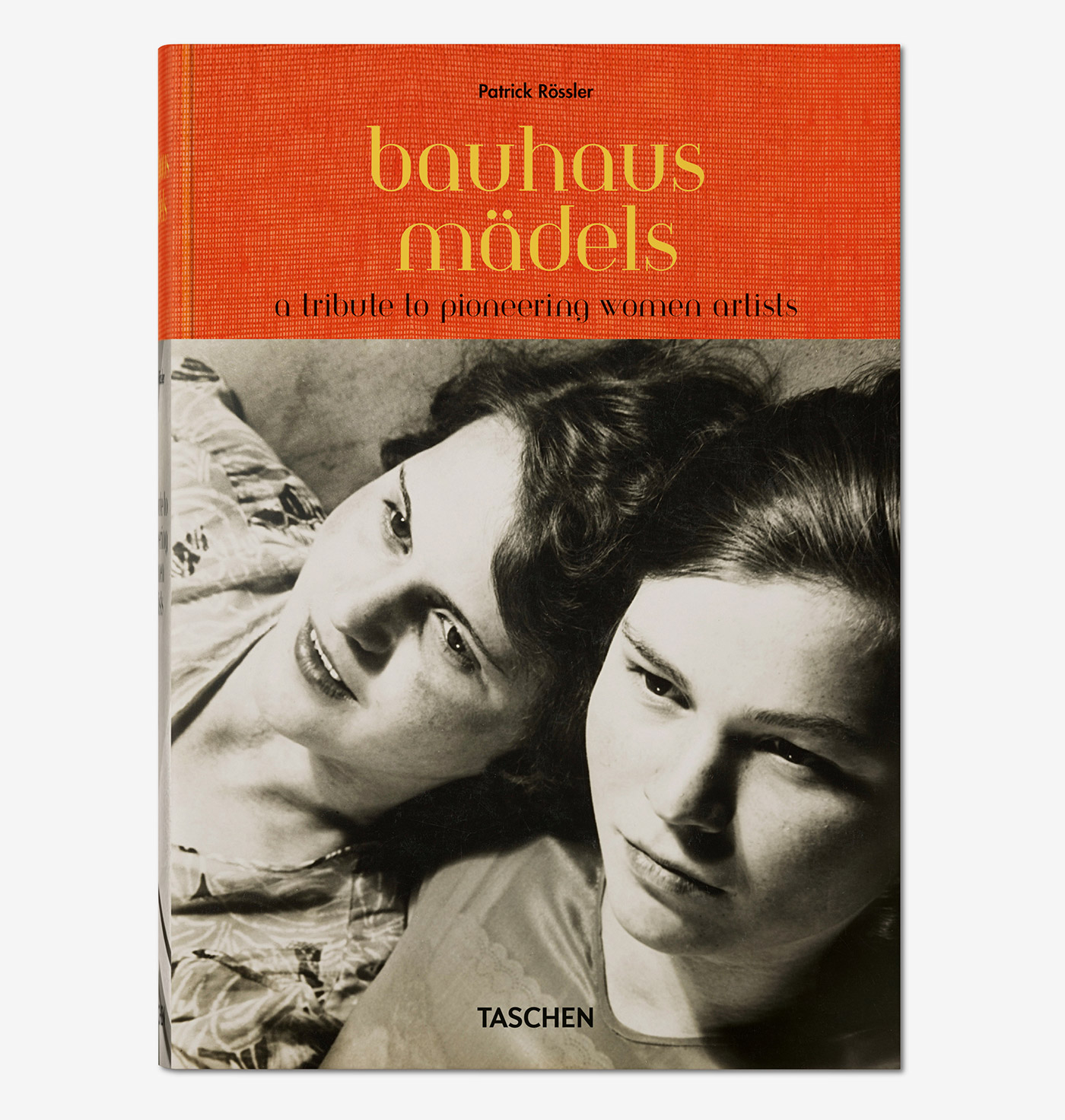

The female side of the Bauhaus story and the remarkable rise of the Bauhausmädel (‘Bauhaus girl’) is explored in depth in a new Taschen book, bringing together the lives of many women who shaped and disseminated their ideas, with little or no recognition in their day. (The captions for photographs illustrating the original article on the Bauhaus woman had been published anonymously, perhaps written by a woman, since women were not considered appropriate contributors to magazines at the time.)

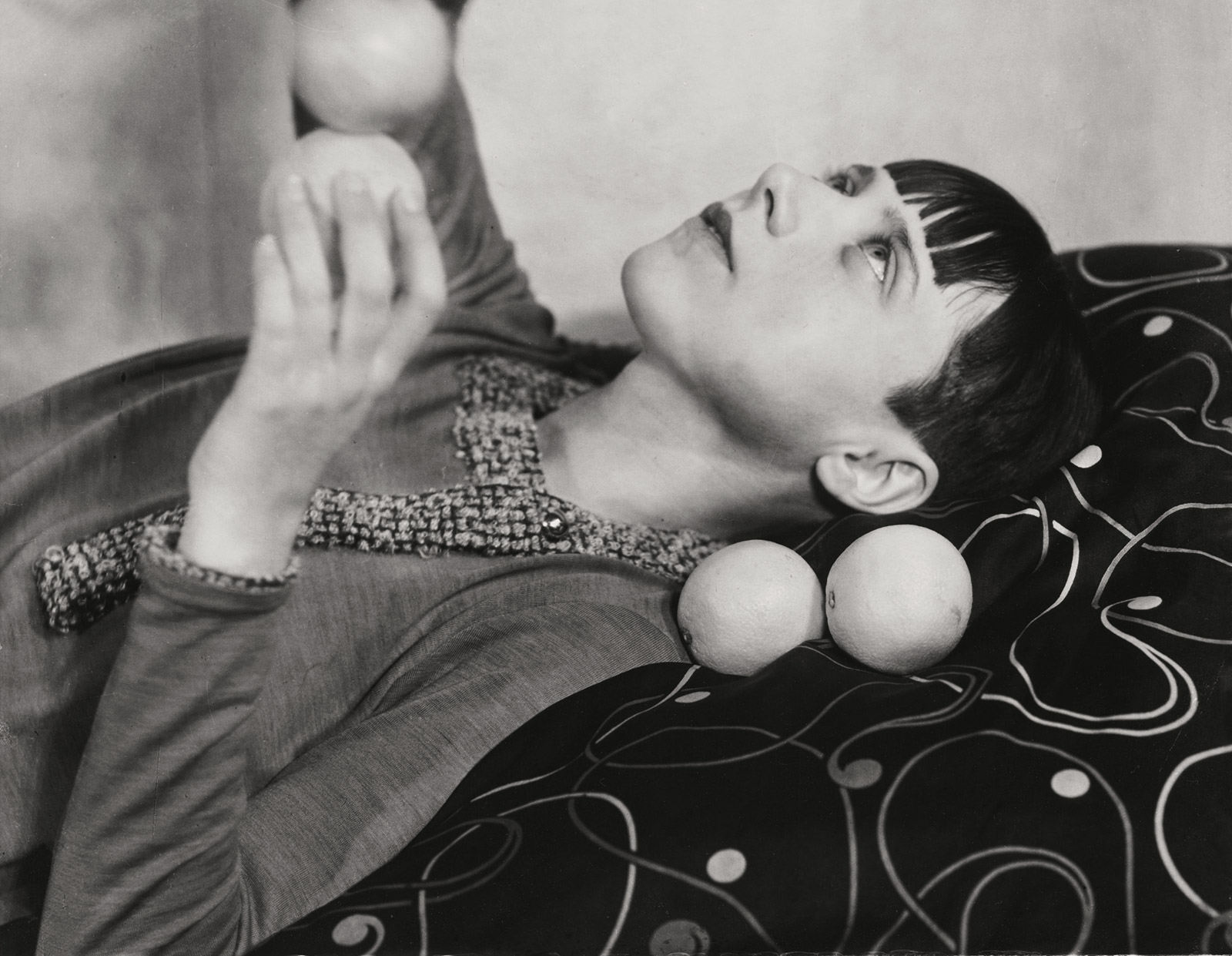

Margaret Leiteritz with oranges, before 1930.

Among them is Ricarda Schwerin, an atheist who, aged 18, went to the Bauhaus to study photography. A few semesters in, she had to stop her studies due to poor health, and when she recovered the school refused to have her back. She wound up in Frankfurt am Main with her future husband and fellow Bauhaus student Heinz Schwerin who, like Schwerin, had been prevented from completing his studies (the school ejected most of its communist students in the spring of 1932). Soon after their vows in Hungary were sealed in 1935, the newlyweds fled to Palestine. Together they opened a wooden toy workshop; Schwerin later founded a nursery for refugee children. Only then did she go back to photography, working for two decades up until her death in 1999, aged 87.

Hers is just one among 87 women who attended the pioneering school of art and design, each of them unique, but facing similar societial expectations and political demands: the Nazi regime pressing down on them, forcing many to emigrate multiple times, and lose husbands to war. Other more famous names include Marianne Brandt, one of the first women to be admitted to the Bauhaus metalworking program, and whose designs continue to be produced by Alessi to this day.

RELATED STORY

The book does not brush over the ‘entirely problematic gender relations at the Bauhaus’, as author Patrick Rössler writes, ‘in particular with regard to the balance of power between masters and students’. As his introductory essay points out, despite its indisputable influence in the world and its inherently progressive ideals, the Bauhaus was shockingly archaic when it came to women. The tome bursts forth to right that wrong and put the Bauhaus women unequivocally back in their place, with their photographs – some of them sumptuous self-portraits – and biographies organised as a timeline of life events. For all of their achievements, many of their lives did not end well.

Bauhausmädels: A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists, published by Taschen

Unfortunately, given the erasure of these women from history, there is no real documentation of their works, only portraits of the women, which after a while seems to put the emphasis on what they looked like, rather than the importance of their contributions to the Bauhaus and its legacy. Among the few works are a series of nude photographs by Lucia Moholy, irreverent, whimsical and free. Moholy’s took iconic photographs of the school’s teachers and of the new Bauhaus buildings, but the negatives were withheld by Walter Gropius and only eventually returned to her in 1959.

The ultimate lesson of the Bauhaus girl might come from that 1930 Die Woche article: ‘The Bauhaus girl knows what she wants and will make it anywhere’ – no matter who, or what, tries to hold her back.

Group photo in the weaving workshop, Dessau Bauhaus, 1928.

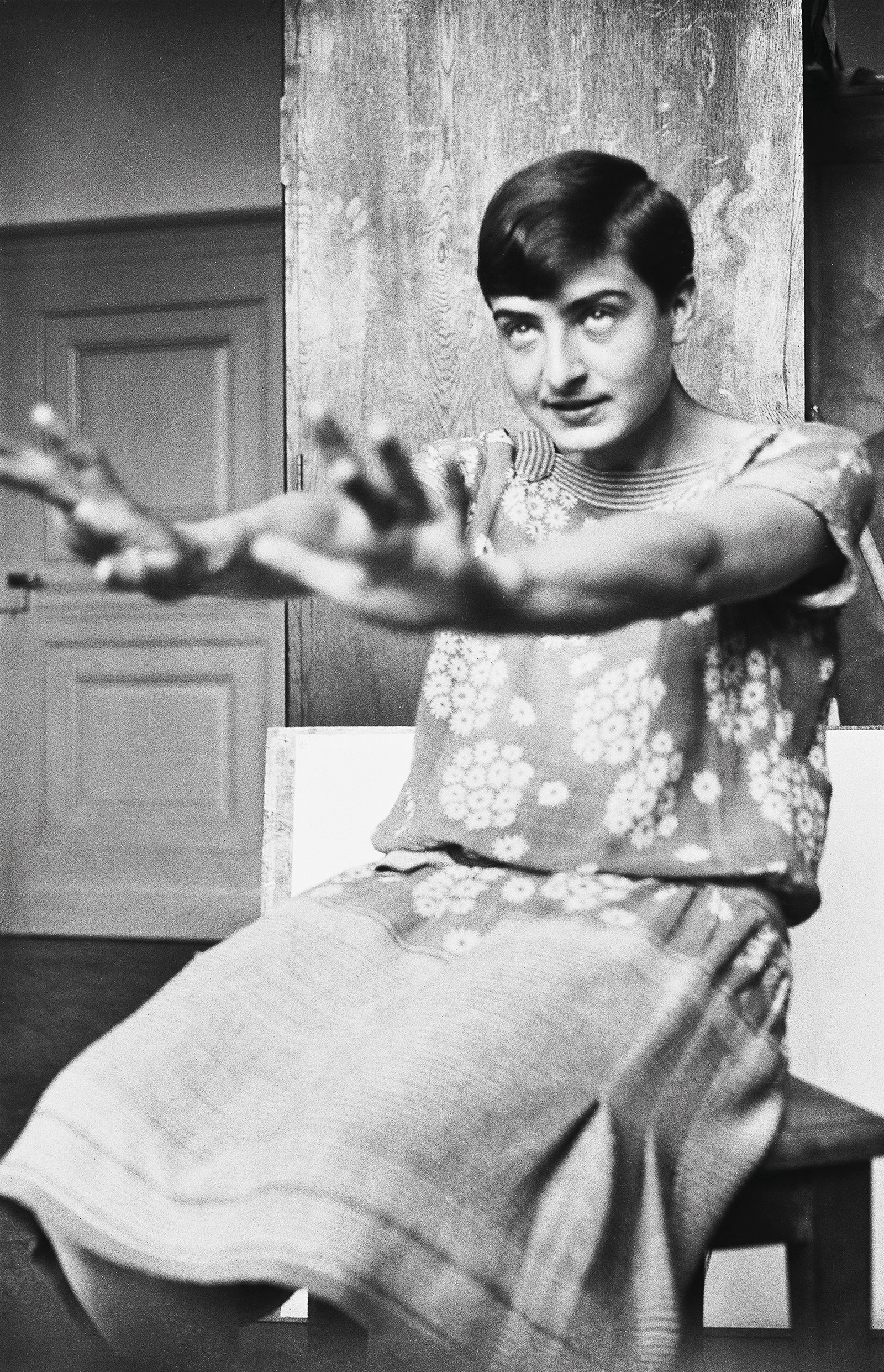

Ellen Rosenberg, the future photographer Ellen Auerbach, 1927-1928.

Hilde Hubbuch in the Haus der Rheinischen Heimat, Cologne, 1928.

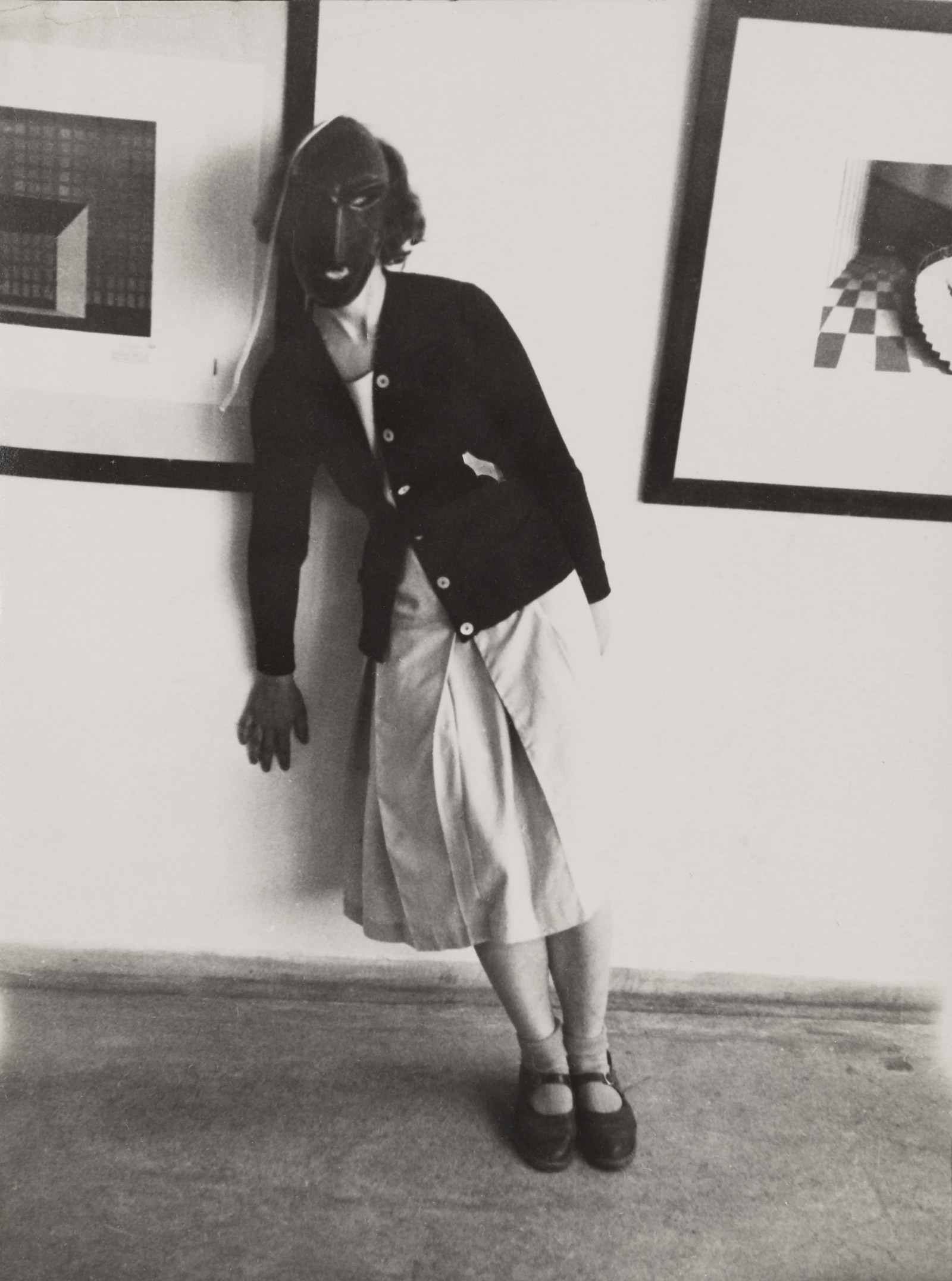

Bauhaus student in a mask from the Triadic Ballet, circa 1927.

Albert Braun photographing Grit Kallin in the Atelierhaus, Dessau, 1928.

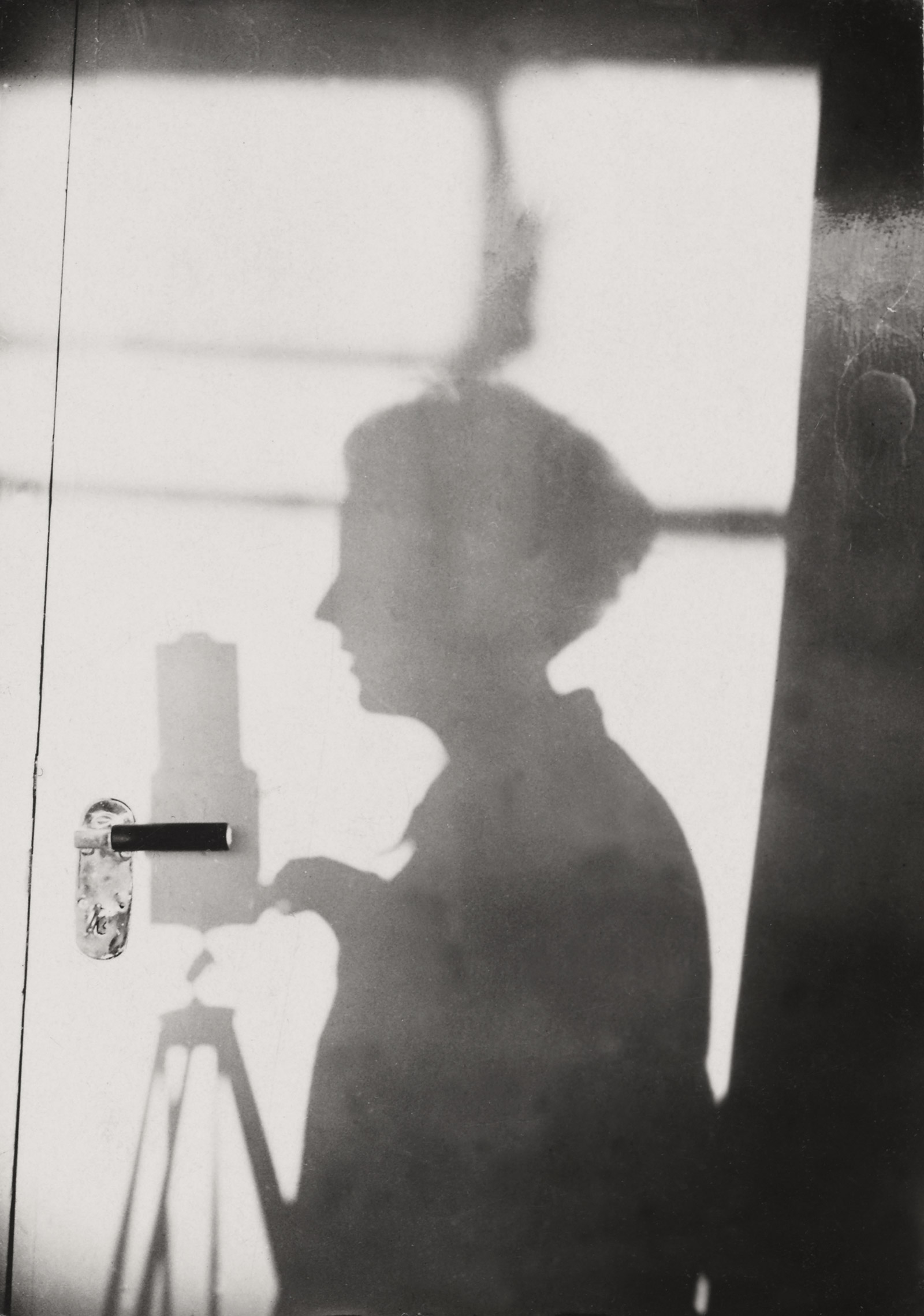

Self-portrait with camera of Lotte Beese (silhouette), 1927.

INFORMATION

Bauhausmädels: A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists, £30, published by Taschen

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.