At home with artists Langlands & Bell

Even in a period of social distancing, the art world continues to turn. In our ongoing series, we go home, from home, with artists finding inspiration in isolation. We caught up with the duo at home in their self-designed rural idyll in Kent to talk birdsong opera, the secret to creative longevity and their forthcoming project on Ghana's slave forts

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

For Turner Prize-nominated Ben Langlands and Nikki Bell, ‘there is no art without risk’. Their work has seen them venture into the former house of Osama bin Laden, probe the architecture of Silicon Valley, and more recently, submerge themselves in the life and work of Sir John Soane. Through their own distinctive language, the artists dissect our rapidly evolving systems of communication, our experience of the structures we construct and our increasingly hazy relationship with the truth.

Later this year, they will unveil their solo exhibition at Ghana’s Gallery 1957, a poignant, meticulously researched project on the complex and devastating history of the country’s coastal ‘slave forts’, built by European slave traders. In their four-decade career, Langlands & Bell have created films, sculpture, digital media, installations and full-scale architecture, including their own Kentish home-studio, where we tracked them down (virtually) to discuss past, future, and quite a lot in between.

Wallpaper*: Where are you as we speak?

Langlands & Bell: At the moment we’re in confinement at ‘Untitled’, the house and studio we designed and built in deepest Kent. We’re lucky, although it’s only 50 miles from London, it’s on its own in a rural area with a beautiful view and feels quite remote. All we can hear is birdsong, and the sounds of dogs, ducks and chickens at the neighbouring farm about 500m away.

Portrait with English Komenda, 2019.

W*: Your creative partnership spans more than four decades. What’s the secret to such a long and fruitful collaboration?

L&B: Mutual respect, tolerance, curiosity, and new work challenges.

W*: You’ve created everything from intricate architectural models to a full-scale bridge. What do you find so fascinating about studying social and political relationships through our built environments?

L&B: All our work starts from an intuitive response to something we discover. We think the things we build, and our surroundings, say so much about us as people and how we relate to each other over time.

Conversation Seat, 1986.

W*: Much of your work involves taking risks and confronting complex subjects. What is the most challenging project you've worked on to date?

L&B: Every project we work on is challenging in different ways. Whether it’s going to Afghanistan to research and make art about the devastating conflict there, making new work in response to the densely historic and highly personal environment of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, or responding to the terrible legacy of the Atlantic slave trade and Britain’s deep involvement in it. We challenge ourselves because we find all of these subjects interesting and new challenges give rise to new outcomes in our work. There’s no art without risk.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: Which career moment will you never forget?

L&B: There have been so many moments it’s hard to pick one out!

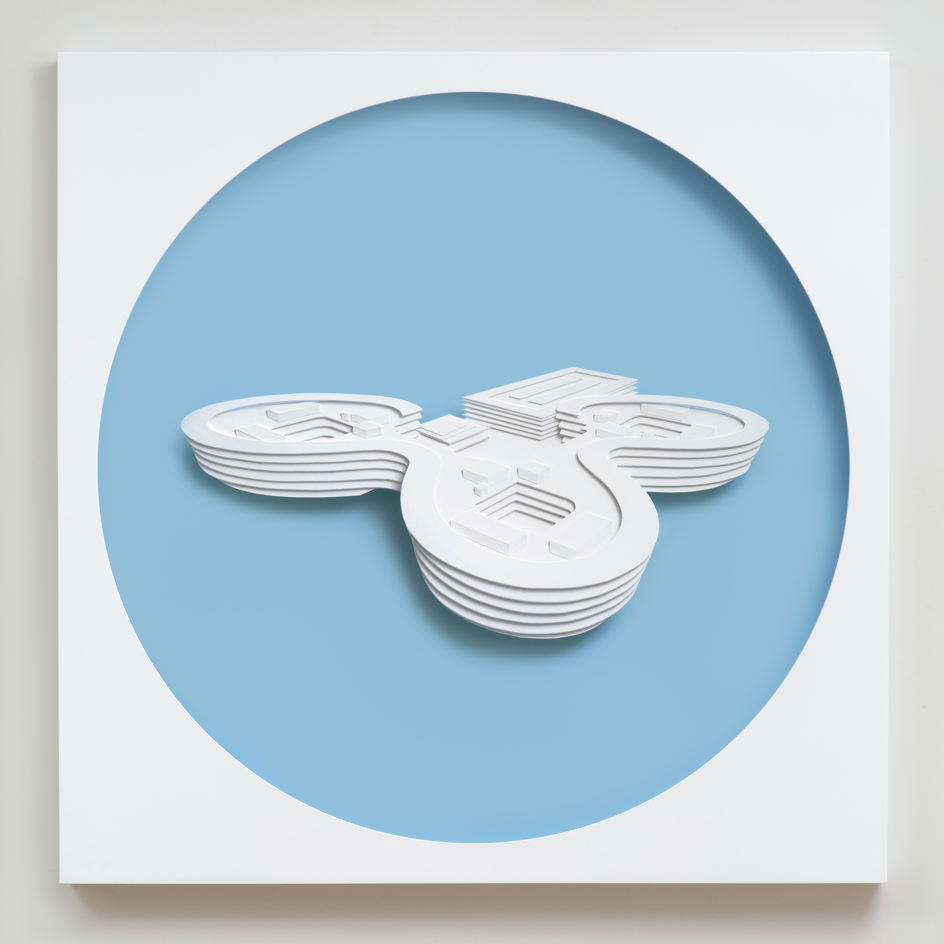

Apple, Sunny Vale, 2017. courtesy of Langlands & Bell

W*: Your forthcoming exhibition, ‘The Past is Never Dead…’ at Accra’s Gallery 1957 explores Ghana’s historic coastal slave forts. What drew you to this subject and what was the most surprising thing you learnt?

L&B: Initially, we were interested in the slave forts as historic architectural sites. Each one has a unique and terrible presence but they all share a common language. They tell the story of unequal power relationships between Europe and Africa over centuries, of unfettered mercantile opportunism and exploitation, and the human destruction and absolute misery that resulted. Architecture has this ability to convey the irrefutable truth about a situation in a way that few other things can. Today Ghana is the custodian, but the slave forts are a shared history – of relations between Africa, the Americas and Europe. They have witnessed horrors that are almost unimaginable to us. They are the link that shows what people are capable of at their worst, and the resilience they are capable of at their best.

RELATED STORY

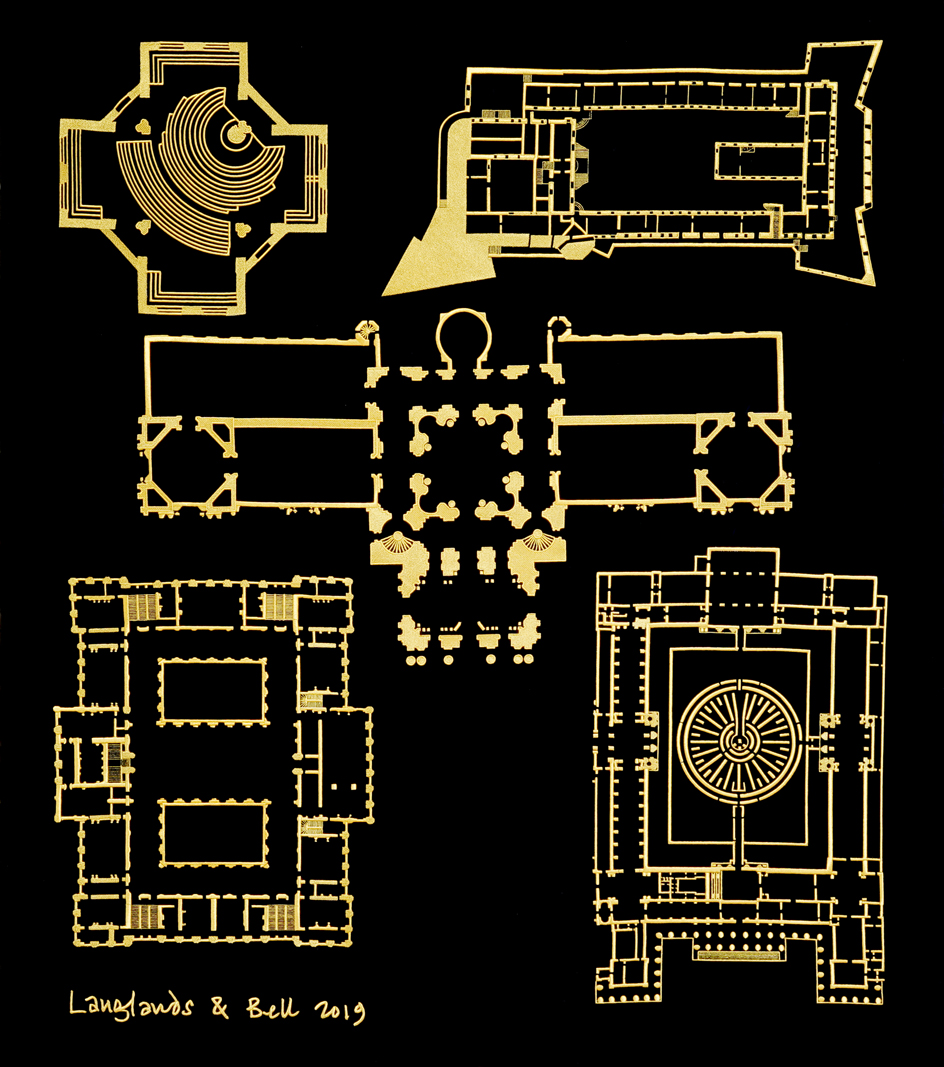

Palaces of Culture (Europe), 2019 for The Past is Never Dead...'.

W*: Can you describe a few pieces you’ve created for ‘The Past is Never Dead...’?

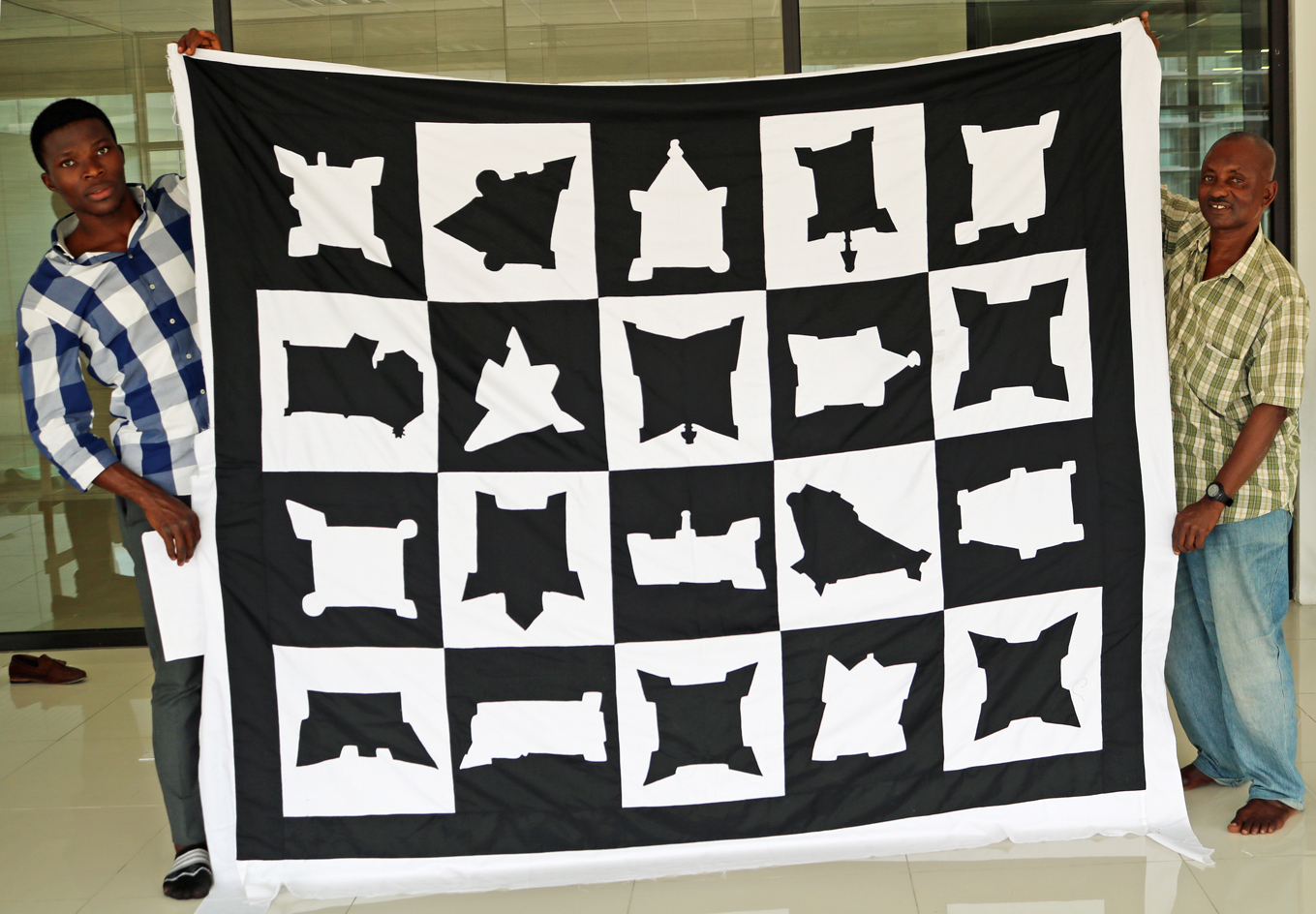

L&B: One of the many wonderful things about working in Ghana is the great range of cultural traditions and skills. On the coast there’s a long and vibrant tradition of flag-making, so we’re collaborating with a local master to produce tapestry works in cotton appliqué based on the plans of 20 of the slave forts that we researched on the ground and in archives in Ghana, Amsterdam and London. The plans bear an uncanny resemblance to some of the Adinkra symbols, a visual language of pictograms used widely throughout the region.

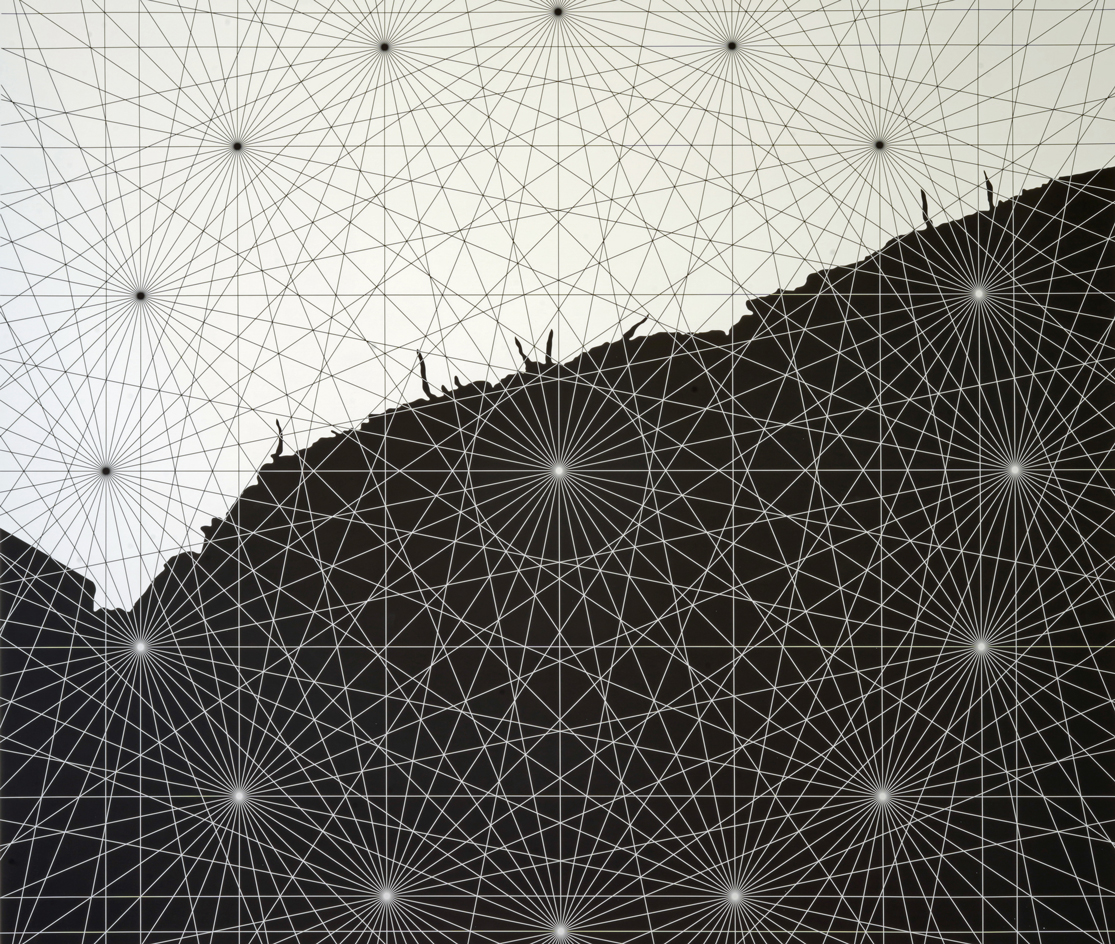

We’re also collaborating with a local woodcarver to produce a sculpture based on the Dutch state chair of the last governor of Elmina Castle – the oldest and the largest of the slave castles, originally built by the Portuguese but later taken over by the Dutch and then the English and used as their headquarters of the Gold Coast – that we discovered in a room at the fort of St Anthony at Axim in the West of Ghana. We’re making new works on canvas that re-interpret the extraordinary ‘wind charts’ used by the European mariners to navigate the coast of West Africa, and new sculptural reliefs that feature models of the forts with double-gilded mounts and African redwood frames.

Asafo master Baba Issaka and his son hold up The Past is Never Dead…, 2020, a new cotton appliqué tapestry with the plans of 20 Ghanaian slave castles

W*: How are you adapting your ways of working to the era of social distancing?

L&B: As artists, we’re used to working on our own for protracted periods of time and we’re very adaptable in the different ways we work. The main difficulty we’re all facing in the art world at the moment is how to show the works we spend so much time making!

W*: What’s the most interesting thing you’ve read, watched or listened to in the last month?

L&B: We loved watching Grey Gardens, the documentary film by Albert and David Maysles made in 1975 about two reclusive, eccentric, upper-class relatives of Jackie Onassis slipping into poverty in a decaying mansion in the Hamptons on Long Island. Then we watched the wonderful film about them with Drew Barrymore and Jessica Lange made 35 years later by Michael Sucsy. Both films brilliantly observed, filmed and acted. Very moving.

We’ve just started reading The Atlantic Sound by Caryl Phillips, a gripping re-examination of the slave trade and the way its terrible legacy still reaches far around the world and implicates us all.

Listening… a friend just sent us the little ‘Bird Song Opera’ film by email. It really lifts the spirits!

’Bird Song Opera’. Courtesy ShakeUp Music & Sound Design

W*: During the isolation period, have you developed any new interests?

L&B: Yes, on our walks we’ve been picking wild garlic and making tortilla Española together with eggs laid on the day bought ‘remotely’ by putting money in an honesty box.

Top, Wind Routes of the Gold Coast, 2020, for 'The Past is Never Dead...'. Image courtesy of Langlands & Bell Globe Table, 2020. Bottom, a sculpture incorporating an 'abstract globe' of the air routes of the world created for 'Degrees of Truth' at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

INFORMATION

langlandsandbell.com

gallery1957.com

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.