Wonder walls: a new book celebrates the modernist house as a cultural icon

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

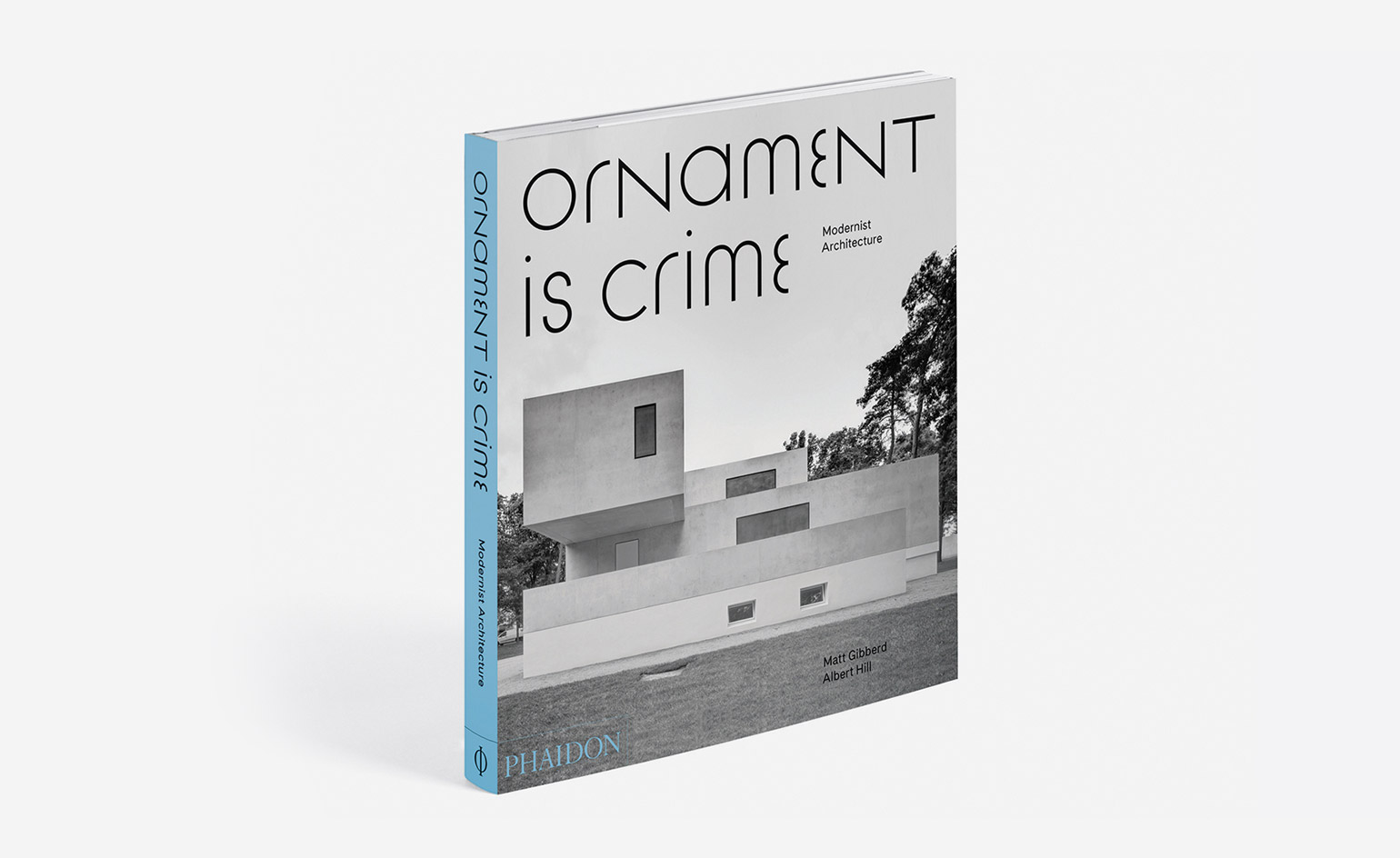

Fetishised in the new book Ornament is Crime: Modernist Architecture, the modern house has never felt so iconic. Editors Matt Gibberd and Albert Hill have curated a visually-led book of black-and-white photographs showing detached modern houses. Modernist architects of the world – from Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe and Eileen Gray, to Sean Godsell and Arne Jacobsen and many more – unite across double page spreads, where houses are organised by formal similarities, regardless of chronology or location.

‘The purpose of this book is to identify its key aesthetic characteristics and show how this most trailblazing of architectural styles is still thriving in the twenty-first century,’ writes Gibberd in the introduction. Here he visualises the great modernist architects as a family tree, with Smiljan Radic, Tadao Ando and John Pawson on the lower branches, and the greats at the top – Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. Yet beyond the introduction, which draws connections between projects through a personal narrative of travels, work and experiences, the main part of the book is strictly limited to photographs of modern houses, and a series of intriguing quotes drawn from a variety of cultural sources.

While the pictorial essay certainly presents a strong argument for the timeless properties of the modern house, it also presents the modern house through a contemporary lens, very different to the early 20th-century context unto which modernism was born – when the style was a ‘response to the gradual erosion of social hierarchies’. Today, after Aldous Huxley, Evelyn Waugh, Bret Easton Ellis, Tom Ford, and a hoard of other cultural figures who have described and referenced the detached modern house, it has taken on a new meaning. Once banausic, the modern house has become an object of fantasy.

Philip Johnson, The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, USA, 1949.

Experts in the intricacies of the modernism, Gibberd and Hill run a unique real estate company, The Modern House, which has materialised the modern house fantasy for many, and now this book seals their visual manifesto – hitting a sweet spot of aspirational decluttered living.

The editors delight in the drama of the modern house – and its reputation, naming the ghostly-looking tome which hosts Bruno Fioretti Marquez’s severe looking Bauhaus Campus at Dessau on its cover, after Adolf Loos’ 1910 lecture, ‘Ornament and Crime’, in which the architect describes ornamentation in design as an erotic plague. Yet, inside the book, these modern houses are seductively unrolled across landscapes and horizons, like white plaster and poured concrete ornaments in themselves.

A contemporary romanticism of modernism runs deep through Gibberd’s brilliantly personal introduction that begins with early memories of his grandfather, architect Frederick Gibberd, who designed the great Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool. Fondly nicknamed Grandpa Black Car, the elder Gibberd was chauffeured around in a vintage drop head Rolls-Royce. Gibberd tells another story of how when found alone with his wife in Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House #22, he attempted to recreate the stock-still interior and taintless glazing preserved in Julius Shulman’s most famous architectural photograph.

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1929.

These anecdotes cement the modern house into a realm of nostalgia and fantasy, which is further enhanced throughout the book by a series of quotes from architects, designers, writers and musicians, that guide the architectural mind off track into a different territory: ‘Sin is the only real colour element left in modern life,’ says Oscar Wilde on one page, while printed above Werner Sobek’s D10 house (2011) in Ulm, Germany, Rafael Moneo says, ‘The building itself stands alone, in complete solitude – no more polemical statement, no more troubles. It has acquired its definitive condition and will remain alone forever.’

Black and white photographs push the imagination into shadowy, cinematic narratives that hint at sadness and discontent. Beside Richard Neutra’s Lovell House in Los Angeles, built in 1929, the words from Leonard Cohen’s Famous Blue Raincoat – ‘I hear that you’re building your little house deep in the desert. You’re living for nothing now, I hope you’re keeping some kind of record’. Nearby, Nina Persson’s Dreaming of Houses and Roxy Music’s In every dream home a heartache. The playlist sings out of excess, loneliness, pride and detachment through the voices of REM, the XX, Coldplay and the Local Natives.

Perhaps by stripping these modern houses of any colour they had to start with, Gibberd and Hill had hoped not to create too much of a seductive coffee table book, that did actually aim to ‘identify its key aesthetic characteristics’ of the modern house, yet, by throwing in these quotes from lyrics written before the economic crash, they have touched upon something that the modern house never really represented before: nostalgia. The book is reduced to a kind of physical Instagram feed and the editors’ salesmen of a modernist dream, targeting a new generation of creative people slipping down the economic spectrum, who may never be able to become homeowners – lost in a capitalist crash and a housing crisis. Like Nina Persson, we might only be able to dream.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, USA, 1951, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Aluminium House, Madrid, Spain, 2016, by Fran Silvestre Arquitectos.

Rothenborg House, Klampenborg, Denmark, 1931, by Arne Jacobsen.

Bass Residence, Fort Worth, Texas, USA, 1976, by Paul Rudolph.

The cover of Ornament is Crime features a photograph of Bruno Fioretti Marquez’s Bauhaus Campus at Dessau

INFORMATION

Ornament is Crime: Modernist Architecture, £29.95, published by Phaidon

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.