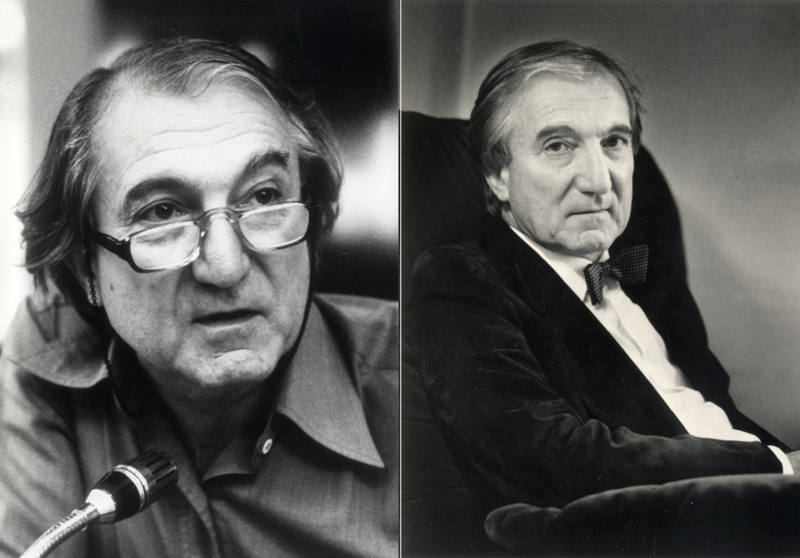

In memoriam: Rifat Chadirji (1926 – 2020)

We look back to the life and work of prominent Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji, considered by many the father of modern Iraqi architecture, who has passed away aged 93

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Rifat Chadirji, the father of modern Iraqi architecture and an accomplished photographer, has passed away after contracting Covid-19. He was one of his nation’s cultural giants, embodying the strengths and the struggles of his homeland. Born into a patrician family with aristocratic, Anatolian roots, Chadirji’s grandfather was once mayor of Baghdad and his father Kamil founded the National Democratic Party in 1946. His life and work were inseparable from the history of Iraq.

He was one of the last of a generation of artists, architects and intellectuals who came of age in the country’s mid-century glory, only to see this dramatically change. His buildings – over 100 of them across Iraq, like the 1975 Baghdad Central Post Office that was damaged and looted in 2003 – bear silent witness to what was once, and what could have been.

After returning from his architecture studies in London, Chadirji became an early member of the Baghdad Modern art group, founded in 1951, that included sculptors Jawad Saleem and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat. While he shared their desire to incorporate Iraqi heritage into contemporary, abstract forms, he remained a modernist at heart, adapting the group’s ideas architecturally into a style he called international regionalism.

Since then, Chadirji’s career spanned the dizzying arcs of Iraq’s path through dictatorship, war and occupation. One of his earliest and best-known works was his Monument to an Unknown Soldier in Fardous Square, commissioned in 1959 by Abd Al Karim Qasim in the days of the July 14 Revolution that overthrew the monarchy.

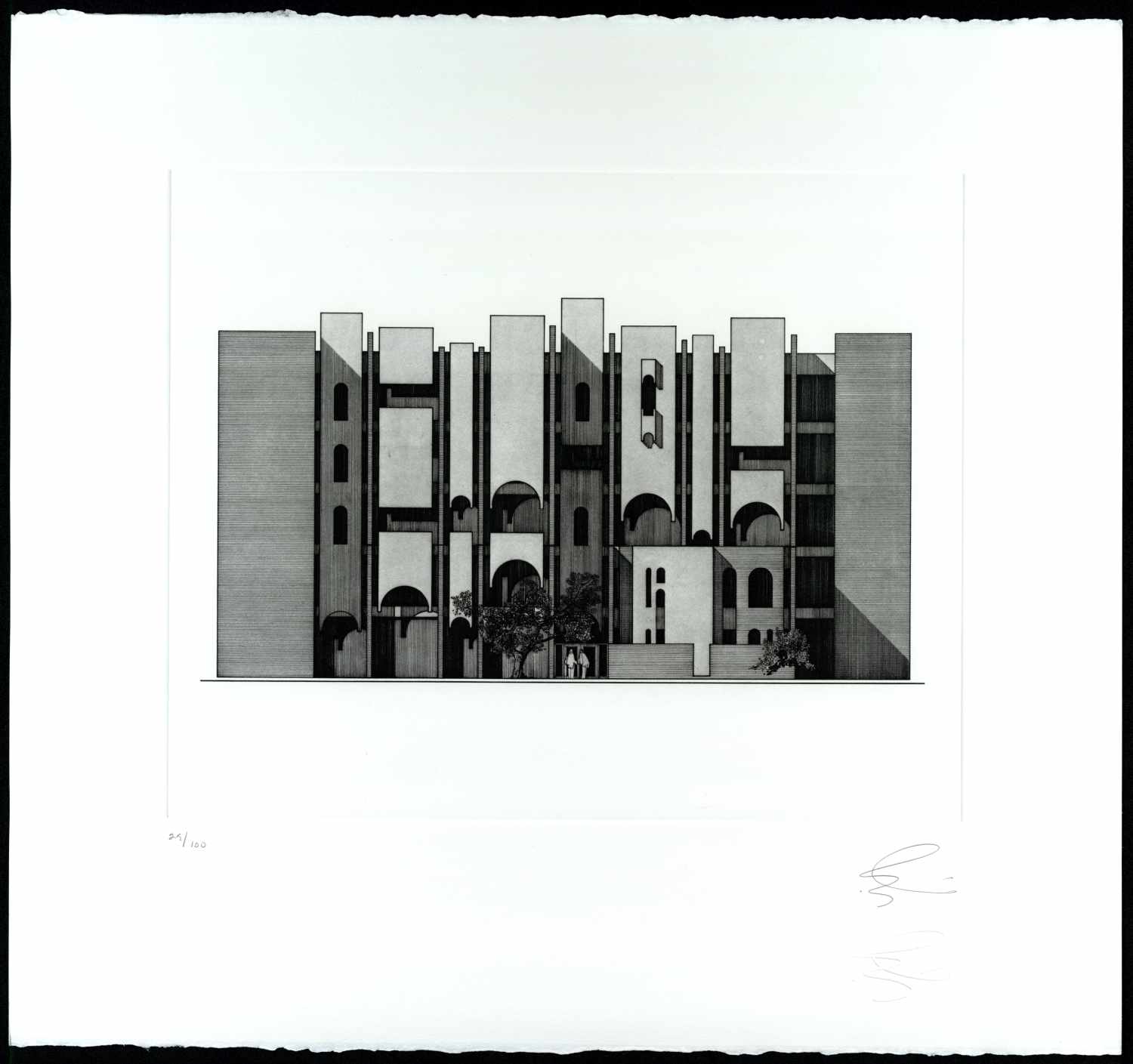

Elevation of Rafidain Bank (1971, Baghdad), from ‘The Architecture of Rifat Chadirji: A Collection of Twelve Etchings’.

In the late 1970s, when Chadirji was at the peak of his career with many international offices, he was put in prison for unfounded charges under the rule of president Hassan al Bakr. It was Saddam Hussein who liberated him; the new president was on a mission to ‘rebuild Baghdad’ for a 1982 conference of Non-Aligned countries and wanted Chadirji to oversee the project. Chadirji went on to commission prominent international architects including Robert Venturi, The Architects Collaborative (TAC), counting Walter Gropius in its founding members.

Chadirji told me in a 2016 interview that he remembered the era as ‘a very good environment’ with a sense of optimism. Still, although Chadirji used his position to stop the demolition of heritage buildings in Baghdad and built theatres and pedestrian bridges, he ultimately left Iraq for good in 1983, when he was offered a teaching position at Harvard. In the meantime, he was elected Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1982, was awarded the Chairman Award of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1986, and elected Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1987.

Although many of the buildings (his own and others, both heritage and modern) that he meticulously photographed over three decades have since been destroyed, Chadirji’s legacy lives on. The Taymouz Excellence Award, founded by young Iraqi architect and academic Ahmed Al-Mallak, gave its inaugural Rifat Chadirji Prize in 2017 to a resettlement plan in Mosul. Sadly, only a year later, Chadirji’s seminal 1966 National Insurance building in Mosul, once a symbol of Iraq’s emerging second city but later tragically tainted by its popularity as a place for ISIS militants to throw victims from its heights, was demolished.

As Iraqi architect Mowaffaq Altaey, who worked with Chadirji on the early 1980s plan for Baghdad, told me, ‘Rifat beautifully expressed the regional and the international. He spoke in two languages, not only one.’

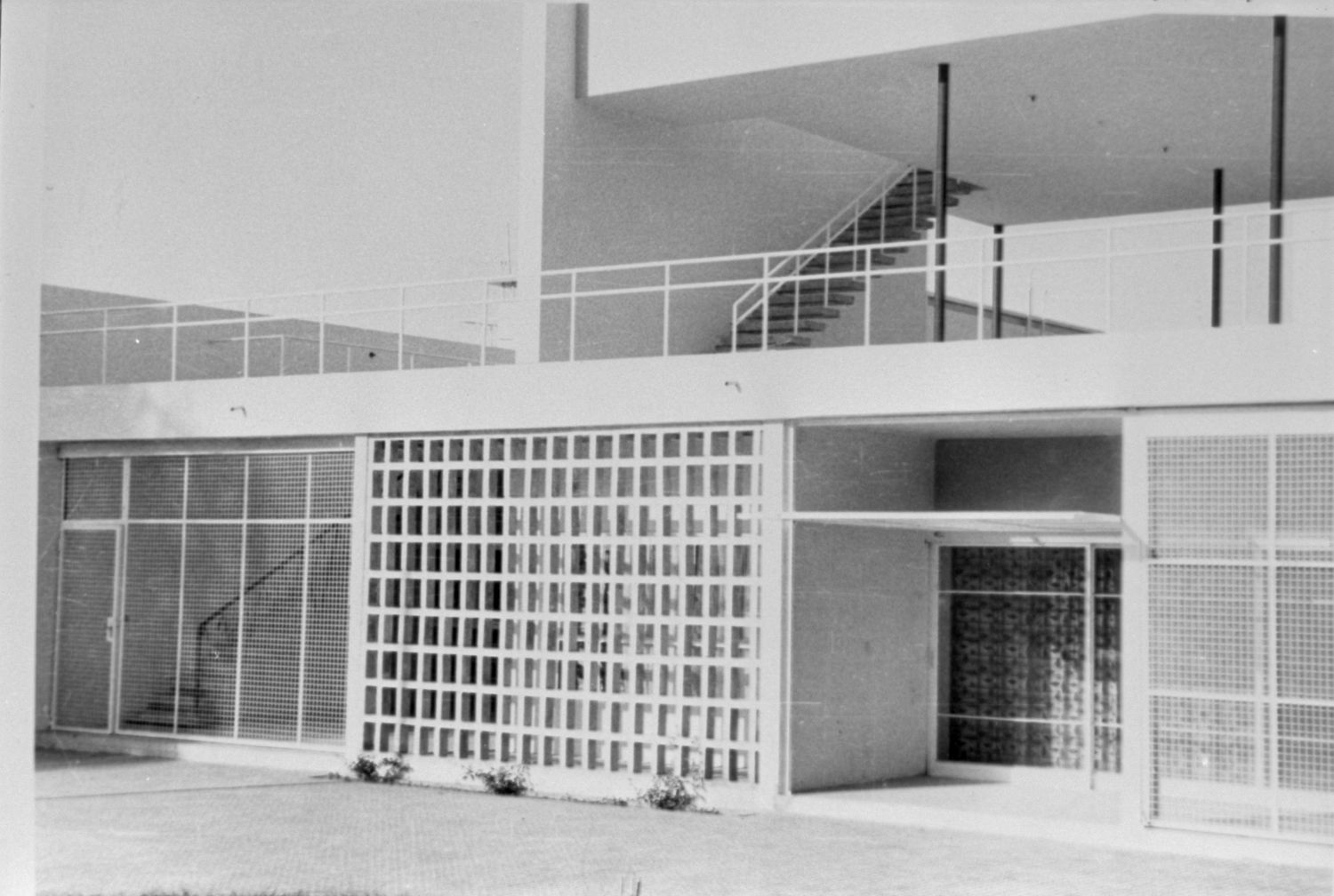

Iraqi Scientific Academy Building, ca. 1965.

Iraqi Scientific Academy Building.

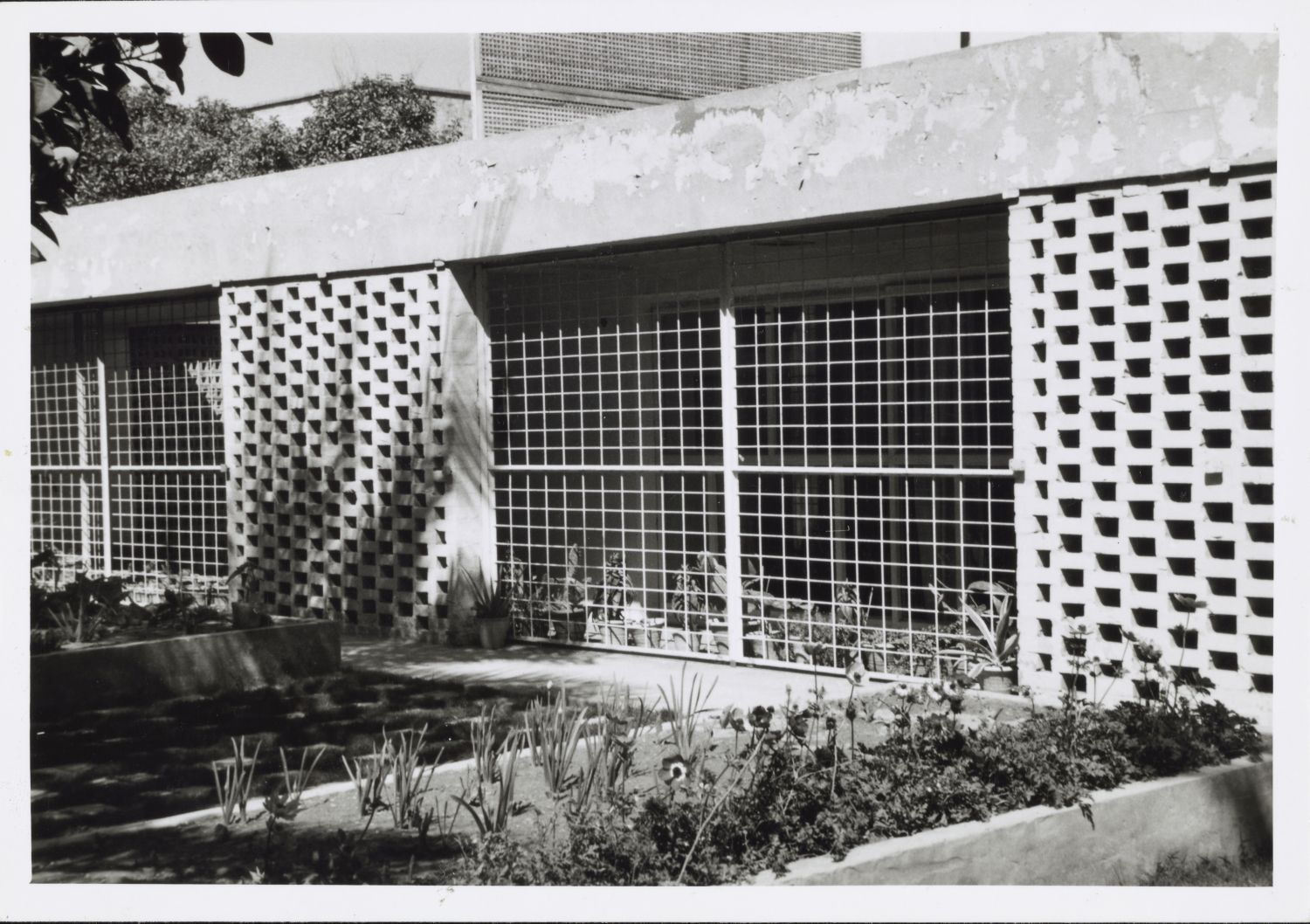

Hussein Jamilji Residence, ca. 1953.

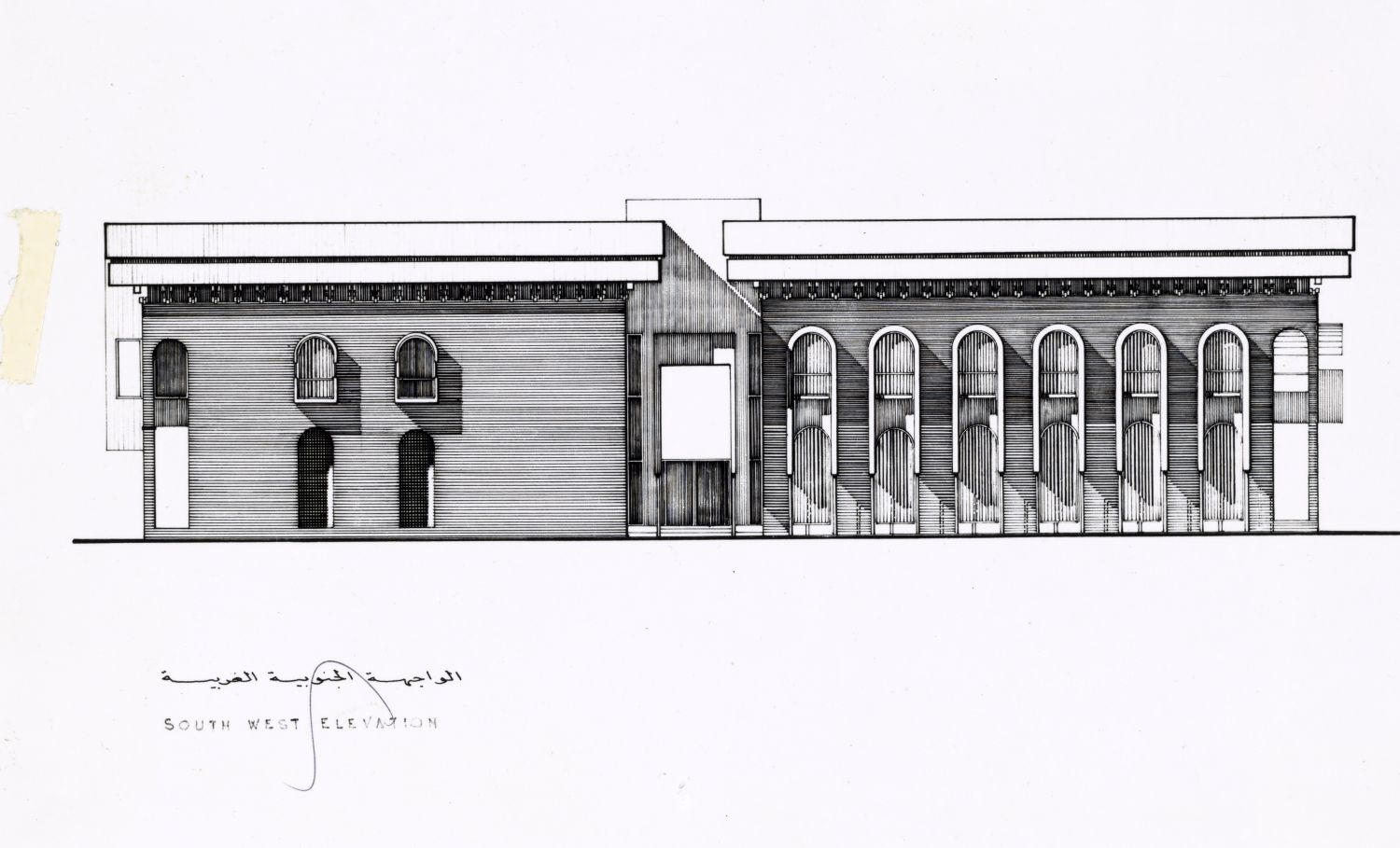

Elevation of London Central Mosque (Competition Entry, 1969, London), from ‘The Architecture of Rifat Chadirji: A Collection of Twelve Etchings’.

Rifat Chadirji Residence, ca. 1955.

INFORMATION

Photography provided by Kamil and Rifat Chadirji Photographic Archive, courtesy of Aga Khan Documentation Center, MIT Libraries (AKDC@MIT)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.