We visit the late artist Manuj Babu Mishra’s studio in Nepal, a treasure frozen in time

The private studio of Manuj Babu Mishra, the late, great artist from Kathmandu, was his entire world – a self-imposed exile where he painted the chaos of humanity; his son, Roshan, invited us to visit

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The chaos of Kathmandu, where Manuj Babu Mishra’s studio is located, has a way of dissolving the moment you step off the main road in Boudha. The constant hum of traffic, the shuffling of pilgrims circumambulating the stupa, and the clatter of commerce fade into a background murmur. On my last visit to the city, I found myself standing before the gate of a house that felt almost like a border crossing into a different time.

I had been meaning to meet Roshan Mishra for years. As the director of the Taragaon Next, Roshan is a custodian of Nepal’s architectural history – a man dedicated to archiving the past. But I was here for a more personal excavation. I was here to see 'The Hermitage', the home and studio of his father, the celebrated and enigmatic artist Manuj Babu Mishra, who passed away in 2018.

Step inside Manuj Babu Mishra’s studio and personal sanctuary

In the courtyard, a stone sculpture of Arniko stands guard. It is a fitting, if ironic, greeting. Arniko was the legendary 13th-century Nepali artisan who travelled to China, taking his craft to the world. The man who lived inside this house, however, did the exact opposite. For the last three decades of his life, Manuj Babu Mishra refused to travel. He refused to attend gallery openings, refused to court patrons, and eventually refused to leave his house altogether. He retreated into this compound, turning a few rooms on the ground floor into a universe vast enough to contain his wildest, and often darkest, visions.

On a bright day in Kathmandu, Roshan met me in a café and eventually took me to the studio. 'This was his space,' he said, unlocking the door to the studio.

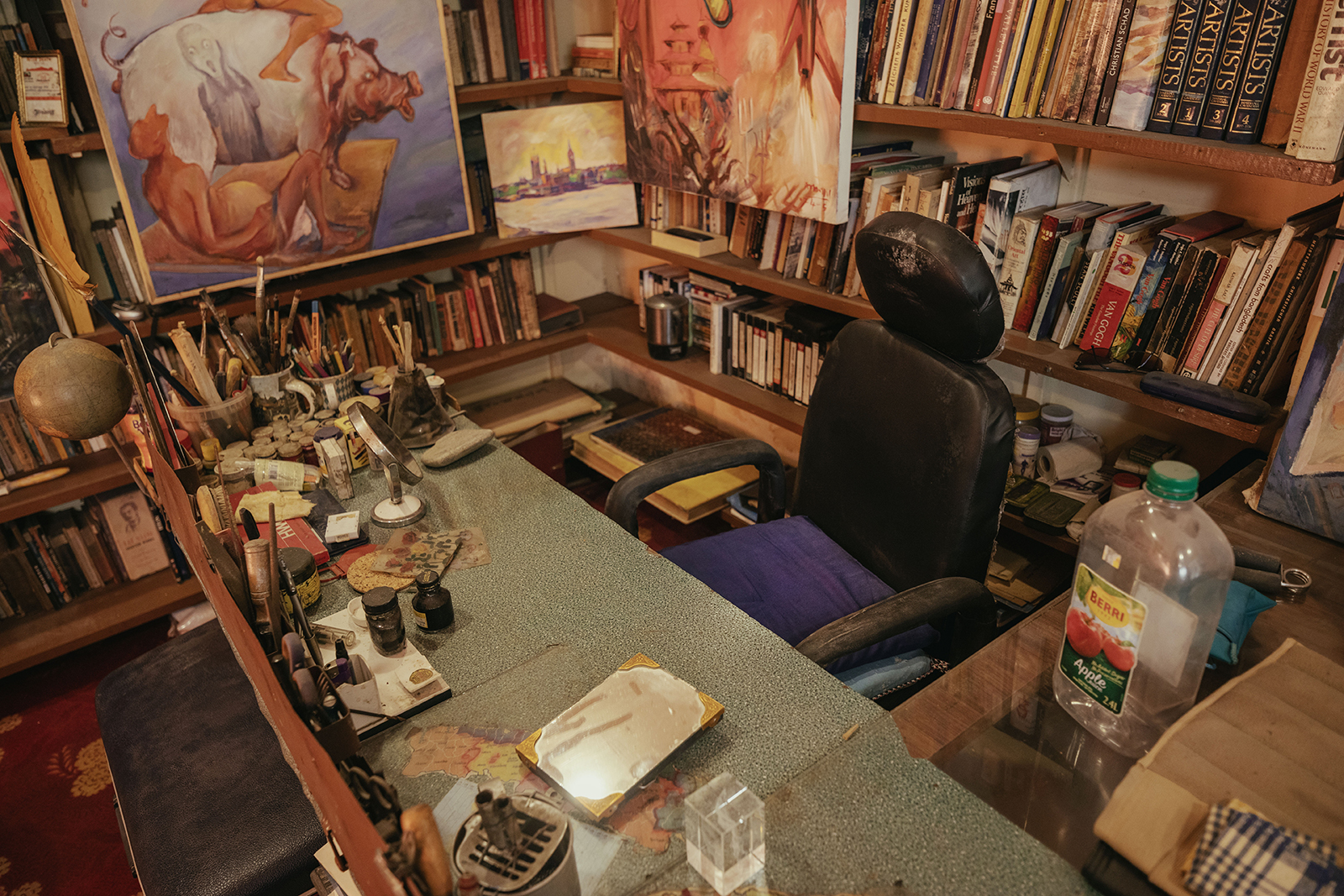

To call it a studio feels inadequate. It is a cockpit. It is a bunker... When an artist passes away, their workspace is usually cleared, catalogued, or repurposed. But here, the air feels heavy with a presence that hasn’t quite left. Since Manuj’s death, Roshan has kept the room in a state of suspended animation. It feels visceral, almost voyeuristic, as if the artist has simply stepped out for a cup of tea and might return at any moment to pick up a brush.

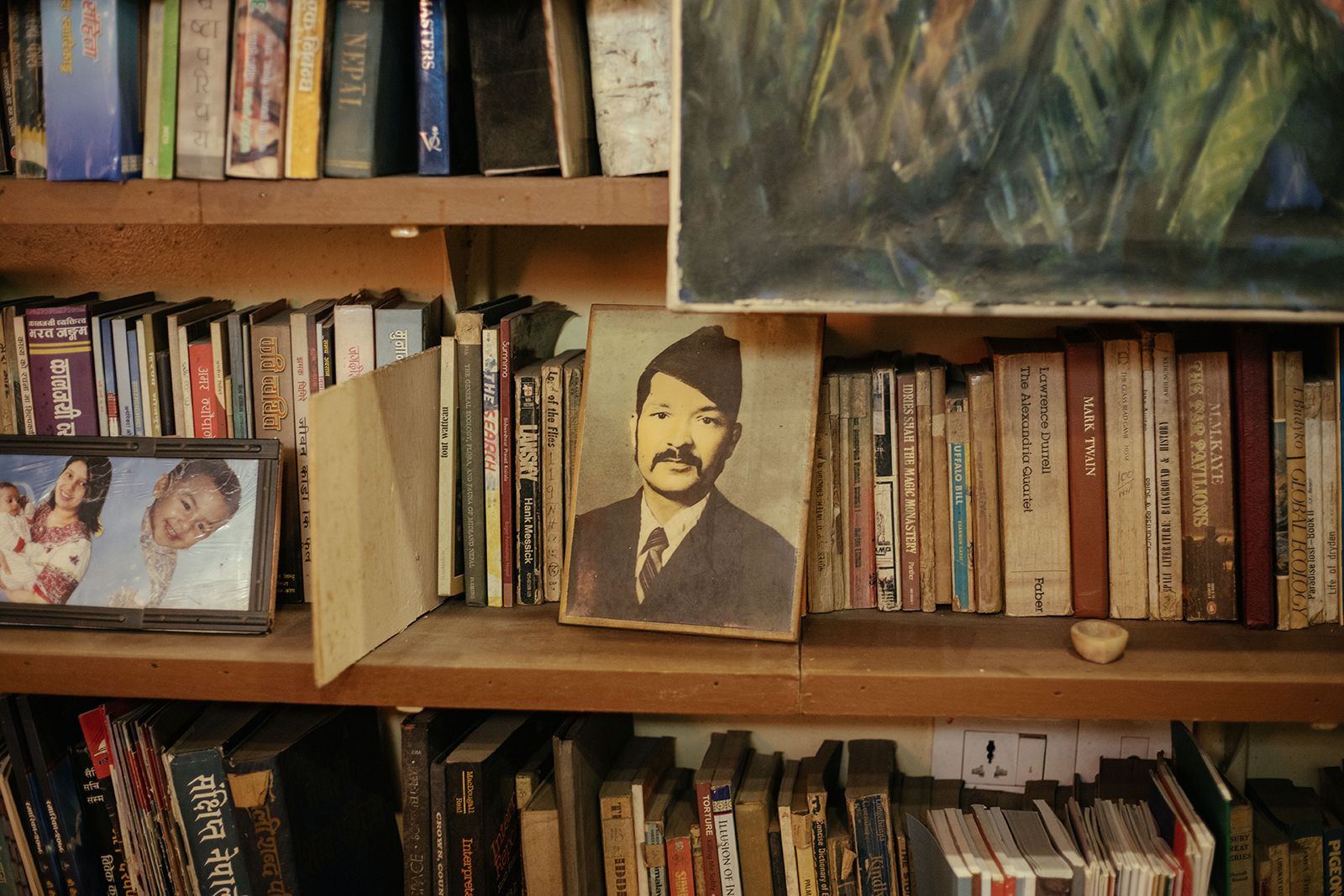

The room is dense. It is not the pristine, white-walled atelier of a contemporary minimalist. It is a cave of intellect and texture. Floor-to-ceiling wooden shelves line the walls, groaning under the weight of books. I scanned the spines: encyclopaedias of The Great Artists, volumes on Max Ernst and Van Gogh, dense texts on philosophy, history, and ancient culture. This library was the fuel for his isolation. While his physical body remained seated in the worn black leather office chair that still sits at the centre of the room, his mind was travelling through centuries of Western and Eastern art history.

The scent of the room is distinct – a mixture of old paper, dust, oil paint, and stale tobacco. The ashtrays (which he made himself) are still there, holding the remnants of his chain-smoking habit. Roshan mentioned that his father would often light a cigarette, take a few puffs, stub it out, and then relight it hours later – a small, nervous rhythm in a life of deep contemplation. My eyes were immediately drawn to the desk. It is the command centre of the Hermitage. Roshan told me his father had it custom-fabricated to his exact specifications, and looking at it, you can see the mind of a man who obsessed over efficiency.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The artist's son, Roshan, now director of the Taragaon Next

The desk’s surface is textured green, cold and smooth to the touch. Running along the entire front edge is a raised metal fabricated organiser, a bespoke invention fitted with loops and compartments. It looks utilitarian, like a carpenter’s workbench. Scissors, pliers, and palette knives stand at attention in their metal holsters. A 'Three Nuns' tobacco tin sits among small bottles of pigments and inks. Everything has a place; everything is within arm’s reach.

It was a setup designed for uninterrupted flow. To the right of the chair, a large, dusty plastic bottle, once containing Apple juice, sits fitted with a long, flexible plastic pipe. Roshan told me that Manuj could sit for hours, painting with one hand and sipping water through the tube without ever having to put down his brush or break his gaze from the canvas. It is a small, human detail that speaks volumes about his intensity. He wanted to be submerged in the act.

On the desk, under a thick sheet of glass, lies a map of Nepal. The paper is yellowing, the borders fading under the weight of years. Resting on top of the glass are a pair of reading glasses and a magnifying glass. It is a poetic still life: the tools of vision resting over the country he chose to withdraw from. He spent thirty years, perhaps staring at this map, even as he refused to walk the streets depicted on it.

Dominating the centre of the desk is a small, circular mirror on a simple metal stand. This was perhaps the most important tool in the room. Manuj Babu Mishra was his own most frequent subject. In the silence of the Hermitage, he would stare into that mirror for hours, studying the topography of his own ageing face. But he didn't just paint what he saw. He painted what he felt. In his self-portraits, he often morphed his features into grotesque forms by adding horns, elongating the nose, and transforming himself into a beast or a demon.

'I cannot see what others think in their minds,' he once famously said. 'But I can see the whole world in my own mind.'

He believed that the beast exists inside every human, a cruel and primal force, Roshan told me. Rather than accusing others, he projected that darkness onto his own reflection. He became the canvas for the world's ugliness. Looking at the mirror now, empty and reflecting only the cluttered shelves behind me, it feels like a portal that has finally been closed.

The walls around the desk are crowded with the results of those long sessions. The paintings here are vibrant, unsettling, and satirical.

To the left of the desk hangs a large canvas from his 'Mona Lisa' series. It is a striking 'Nepali-isation' of the Da Vinci classic. The figure wears a red sari, her forehead adorned with a tika, her neck draped in beads. But behind her, the landscape is a turbulent scene of jagged mountains and surreal figures. Roshan pointed out that the jewellery and clothing in the painting were often modelled after his mother’s - another way the domestic world bled into the artistic one. Next to it, another canvas shows a horned demon riding a pig - a biting political satire. Manuj was deeply disillusioned with the state of the nation.

'He wanted to stay away from politics, whether it was art-related or anything else,' Roshan told me. His solution was solitude. But looking around the room, it becomes clear that solitude did not mean idleness. For Roshan, the studio is no longer just a room; it is a massive, complex excavation site. Since his father’s passing, he has become an archivist, discovering hidden caches of photographs, sketchbooks, and ephemeral notes tucked away in drawers.

'I have mostly archived his drawings, writings, and personal objects simply for my own understanding, to learn more about his life and work,' Roshan explained. Yet, his ultimate ambition is larger: The Mishra Museum. In a country, like many others, where state institutions often fail to preserve the legacies of their artistic giants, the burden falls on the family. 'His life was full of inspiration and stories, and because he was a writer, his work is accessible,' Roshan said, his voice reflecting the weight of the task. 'I don’t want to sell or disintegrate the collection. It is only I who can initiate this, so this museum must be envisioned.'

For all the dark, satirical intensity of the paintings, there are softer artefacts here, too. Tucked amidst the visual chaos are silent testaments to a different side of Manuj: a harmonium, a set of tablas, a benju, and a flute.

Roshan recalls that the Hermitage was not always silent. Manuj would wake early, long before the city began its daily grind, to play these instruments. He would lose himself in the breath of the mouth harmonium or the strum of a guitar. These sessions were a morning ritual, a fleeting moment of melody before he settled into the 'cockpit' to paint the grotesque and the broken.

In a corner, leaning against a stack of books, is a canvas that bridges these two worlds. It is a sketch of Ganesh, the elephant-headed god.

Drawn in rough outlines of red and ochre, with patches of yellow and green that were never fully blended, it remains incomplete. Manuj rarely painted Ganesha; he was a man of darker, more cynical themes. 'He depicted lord shiva very frequently, lord buddha too, much less Ganesh. But he never painted with religious belief.' Roshan told me. But in his final weeks, he turned to this image. Ganesh is traditionally the remover of obstacles, the god of new beginnings.

Walking out of the Hermitage, the transition back to the present day felt jarring. The sunlight in the courtyard seemed too bright, the noise of Boudha too sharp. I looked back at the closed door of the studio. Manuj Babu Mishra had spent thirty years inside, perhaps convinced that the world outside was broken, chaotic, and beyond repair. He had shut the door to paint his own reality. Standing there, I realised that while he had left the world behind, he had preserved something profound in its place. He had left us a room where the music had just faded, the paint never quite dries, and the artist is always just about to return.

Nipun Prabhakar is a photographer, writer, and community architect working at the intersection of memory, migration, craft, and the built environment. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, etc, and he has collaborated with institutions such as MIT, Cornell, and IDS. In 2023, he was invited to present his work at the RIBA’s inaugural Architecture Photography Festival. He is also the founder of the Dhammada Collective.