Architect Byoung Cho on nature, imperfection and interconnectedness

South Korean architect Byoung Cho’s characterful projects celebrate the quirks of nature and the interconnectedness of all things

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When describing his architecture, Byoung Cho often talks about nature. But his connection to it is not achieved through specific physical means – such as materials of a certain provenance, or particular low-tech construction methods. He doesn’t only build on arcadian sites, neither does he forsake dense urban conditions or tall buildings.

At the core of his practice, Cho places ‘interdependent nature,’ a flexible, context-specific take on architecture, centred on the idea of an equilibrium. He cites the Dalai Lama, who first talked about this concept in his ‘The Path to Tranquility’ (1998): ‘We need a clear awareness of the interdependent nature of nations, of humans and animals, and of humans, animals, and the world. I feel that many problems, especially man-made problems, are due to a lack of knowledge about this interdependent nature.’

AYU Space

Byoung Cho and the notion of 'interdependent nature'

Byoung (Soo) Cho broadly defines this as the way ‘nature, people and every living organism interacts and coexists - the social relationships between people, how air flows through a space, the interplay of light and shadow, the passage of time and the weathering of materials.’ He is fascinated by how it is all connected, ultimately shaping our lives, as we, in turn, shape our environment. The Korean architect, head of his namesake studio in Seoul, BCHO Architects since 1994, seeks to explore this relationship between nature, landscape and architecture, as a sense of balance, through his work. On top of this, he layers the traditional Korean concept of ‘ubuntu’. Its rough translation is ‘humanity towards others,’ which promotes an awareness of how one’s actions affects others, and how we are all interlinked.

Growing up in a Korean hanok, he experienced firsthand his country’s traditional architecture, and how it touches the ground lightly – using gentle design gestures, but quite literally too, as hanoks are typically slightly raised from the ground. He also remembers Korea’s growth and change in the 1970s, as it was increasingly influenced by international styles. It inspired him to become an architect (he studied in the US completing a postgraduate degree at Harvard), before setting up shop in his hometown of Seoul.

His career grew slowly and steadily (but he capped staff numbers at 30, so ‘I can have close input in every project’), starting with a series of private residences, such as his 2004 Concrete Box House and his 2009 Earth House. He sees those as the continuation of his Harvard thesis project on the emotional impact of a place. They are both low, minimalist, rural structures about ‘lowering oneself in the ground and being submerged in nature,’ he explains.

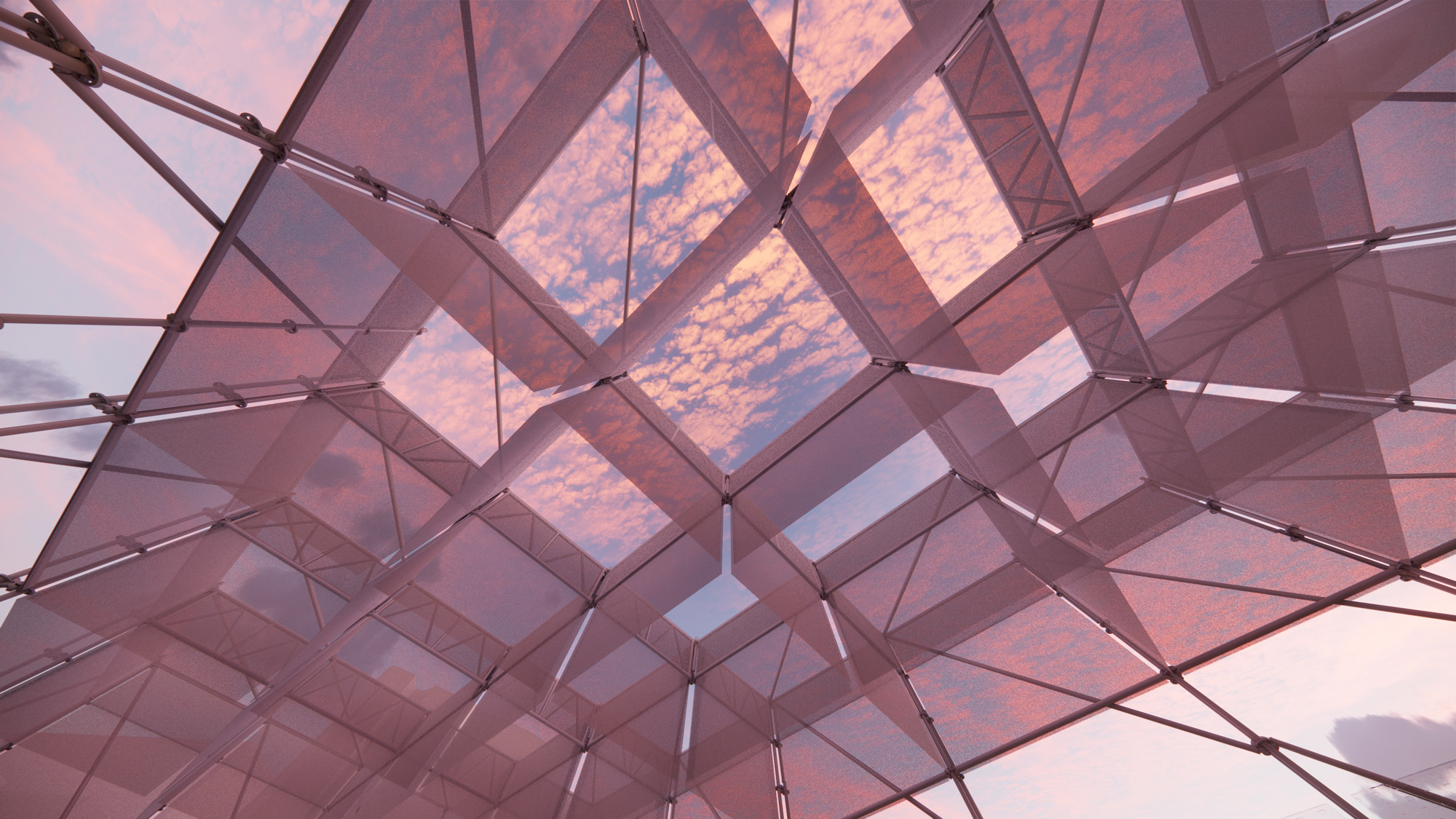

A render of the Sky Project for the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2023, which is curated by Cho

He acknowledges the 2014 Southcape Hotel in Gyeongsangnam-do as a landmark commission, which propelled him to the forefront of his field in the country due to its elegant yet bold design, scale and public nature. It is now due to be extended, and Cho has been busy revisiting his old design to bring it to the 21st century. It’s one of his biggest current works, alongside Saemanguem Seed, a scheme that looks into restoring damaged ground in a former landfill site and introducing nature back in, creating more sustainable architecture, as part of a public library, youth job creation centre and cafe complex some three hours outside Seoul. He has also worked on high rises, including office buildings in the capital, but his approach is always the same, drawing on context and seeking a sense of calm and poise between what he builds and what lies around it.

His latest completion is AYU Space, a flowing, serpentine gallery, restaurant and café complex just outside Seoul for art entrepreneur Miyoung von Platen. It is a project that encapsulates Cho’s approach about humankind’s relationship to landscape, as its terrain ‘ultimately determined the undulating form of the building, creating an unique dynamic experience for the visitors.’ Complementing an existing, 1970s structure next to a traditional hanok, the scheme draws on the site’s dynamic topography to carve a volume that swells and drops around a circular courtyard hosting a dry, meditative, rock garden. The restored hanok hosts exhibitions, while the concrete extension hugs it on one side, containing hospitality. The whole frames vistas towards the nearby river and surrounding nature, making for the perfect viewing platform, projecting a sense of calm, and inviting visitors to take in art, architecture and landscape at once.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

An ink drawing by Cho

Cho is also heading the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2023, which launched this month [September 2023] – the festival’s fourth iteration. He was appointed curator of the event in 2022, and has been working on its programme ever since. His theme, centred on ‘land architecture,’ follows his fascinations, aiming to place landscape, nature, and related ‘social and cultural phenomena’ at the forefront of people’s mind. As part of it, he is crafting two site-specific installations – the Earth and the Sky Pavilion. The latter, in Songhyeon-dong, uses soil from four excavation sites across the country. Their differences in colour and texture become an integral part of the design, symbolising unity and collaboration as part of his ‘interdependent nature’ thinking. The former is an ‘indentation into the ground’, from which visitors can experience panoramic views towards the mountains of the north and the city on the south. He is also particularly excited about the students’ contributions as part of the Global Studio section of the event, where participants were asked to reimagine bridges - themes of connection reappearing.

While his work always looks crisp and elegant, strongly, seemingly, leaning towards minimalism, he believes that formal expression, and the idea of maintaining a certain ‘look’, is overrated in the architecture world. His response tends to favour more conceptual routes, where there’s space for feeling and flaws too. Imprinting personality and allowing imperfections to come through in each project has, for him, value. ‘I prefer more meditative spaces that feel raw and unique. I really value that so many people truly consider working with the environment and not just try to greenwash a project. Being mindful and highly sensitive to what is happening around you is an important skill to have as a designer,’ he says.

Perched on a ridgeline on the island of Namhae, the 49-room South Cape hotel is designed to echo the site’s unique topography

In a bustling office with some 30 projects on the go at any one time, including the biennale, and several teaching and speaking commitments, is it hard for Cho to practise this mindfulness? He’s been an avid painter since his student days and art not only helps him express his creativity, but also has meditative qualities. ‘Art and architecture stem from the same process,’ he explains. ‘The only part that differs is the media used. Instead of shaping buildings, in my art I create shapes in paint on paper. In both scenarios I feel guided by the spontaneous reaction and energy that I call ‘Mahk’ - it refers to the humble action of making that ultimately leaves traces on the finished product. My paintings and my habit of sketching early in the morning are means to preserve this essence of Mahk. In a busy world these moments energise me.’

‘My Life As an Architect in Seoul’ by Byoung Cho (Thames & Hudson) comes out in September

The Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2023 will run 1 September to 29 October 2023

This article appears in the October 2023 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print from 7 September, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).