Heatherwick Studio: Designing the Extraordinary

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The rise of Thomas Heatherwick says a great deal about the fragmented state of visual culture, as well as our collective understanding of the way architecture and design gets commissioned, constructed and publicised.

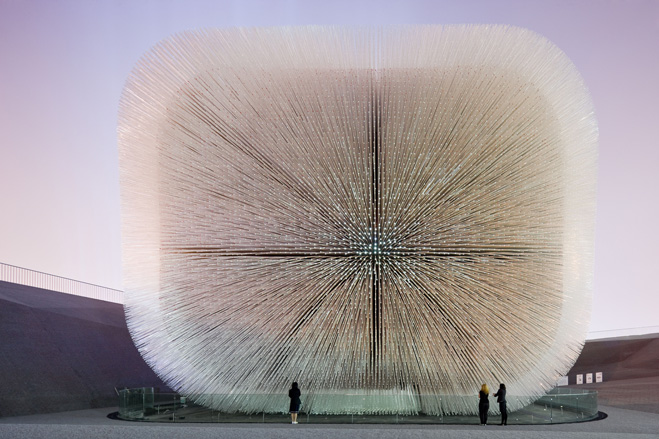

To the general population, Heatherwick is now best known as the man behind the new London bus and the UK's pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. This breadth of ability implies that the studio is similar in scope to any number of big design agencies, as adept at branding, strategy and marketing as the actual art of design. But in truth, Heatherwick Studio has grown out of a very hands-on tradition, that of the artist-maker, the craftsman, the master builder and the artisan. In a world where creativity is predominantly a digital process, Thomas Heatherwick has injected an analogue sensibility.

The designer's earliest projects from his days at Manchester Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art explored the limits of everyday materials, twisting wood, sculpted clay, bent metal, combining hand and machine processes to produce baroque, ornate forms that were still structurally sound and efficient in their use of materials. Gradually, the work evolved from furniture to shop fittings, public art installation and exhibition design all the way up to whole buildings, vehicles and more.

Signature pieces, such as the Harvey Nichols installation of 1997, the Rolling Bridge of 2002 and the ill-fated B of the Bang sculpture are paired with quirky Christmas cards and elaborate but unbuilt projects. Along the way, Heatherwick Studio has functioned as a think tank, often setting itself probing questions or complex tasks and then seeing what technical innovations are needed to solve them.

In 2001 Heatherwick took part in the now-defunct Conran Foundation Collection show at London's Design Museum, in which a sole guest 'collector' was given £30,000 to assemble a gallery's worth of inspirational objects. The designer responded by assembling 1000 things, drawn from all spheres of life and corners of the globe, but all demonstrating an evolutionary quirk or visual eccentricity that transformed them from the familiar into the useful and unusual.

'Designing the Extraordinary' doesn't come close to replicating that earlier show's innate strangeness but it has a certain chaos all of its own. Housed in the V&A's Porter Gallery, immediately adjacent the main entrance, the show is a wunderkammer of engineering experiments.

As Heatherwick himself noted at the opening, most of the pieces on display have been taken directly from his Kings Cross studio, from full-scale components to quick and dirty maquettes. 'When you put 8mm acrylic around something, it transforms it,' he said dryly at the private view and the end result is akin to a Renaissance capricci, a staggered, tumbling peripatetic cityscape of things stacked deep against the tall walls of the gallery. Wind a crank to receive a gallery guide from the Heath Robinson-esque contraption by the gallery doors and you set off on a grand tour, soaking up projects realised and waylaid, all brought together in a mad jumble of ideas and materials.

Heatherwick has succeeded because he combines so many disciplines in an era of cross-disciplinary chaos; he is, in the words of many media profiles, a 'Renaissance Man' in the mode of Leonardo or Buckminster Fuller, a polymath whose talent and curiosity lead him to constantly push for fresh new solutions that make the rest of the world look staid and reactionary.

There's a faint whiff of sour grapes from the architectural community, who grumble about commissions for buildings going to someone who is manifestly not an architect. We suspect this is because Heatherwick has almost single-handedly reclaimed the 'designer-as-hero' narrative from the architectural profession, and architects miss the reflected glory.

Heatherwick is undeniably talented and engaging, but there's also a strong vein of humour running throughout, a quality almost entirely absent from the design profession as a whole. Heatherwick and his team never descend into whimsy or the clumsy 'quoting' of Post Modernism. Instead, ideas are allowed to evolve, taking the technical expertise of the studio along for the ride.

This is perhaps his most important legacy - the reintroduction of the atelier. Heatherwick Studio brings together some 80 professionals, including architects, designers, technicians and writers, and their approach is unified and coherent. Of course, cross-disciplinary studios are a mainstay of modern practice, but few designers can lay claim to such a broad spectrum of experience. For this reason, Heatherwick is a tough act to imitate, let alone follow, leaving one of Britain's brightest - and still youngest - design talents with the world at his feet.

Teeside Power Station, Stockton-on-Tees, Teeside, 2011

Housed in the V&A's Porter Gallery, immediately adjacent the main entrance, the exhibition is a wunderkammer of engineering experiments from Heatherwick Studio

Most of the pieces on display have been taken directly from Heatherwick's Kings Cross studio, from full-scale components to quick and dirty maquettes. The result is a tumbling peripatetic cityscape of things stacked deep against the tall walls of the gallery

New Bus for London, 2011

UK Pavilion Seed Cathedral, Shanghai Expo China, 2010

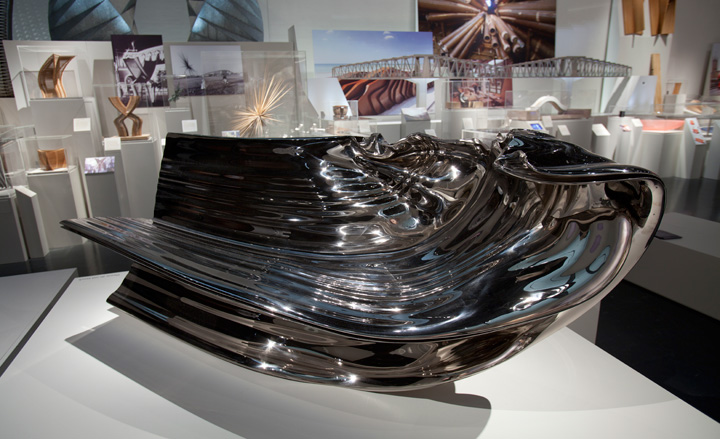

Extrusions, Haunch of Venison Gallery London, 2009

Extrusions, Haunch of Venison Gallery, London, 2009

Bleigiessen at the Wellcome Trust, London, 2005

Vents, St Pauls, London, 2002

ADDRESS

V&A South Kensington

Cromwell Road

London SW7 2RL

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.