Take a trip to Tbilisi, where defiant creatives are forging a vibrant cultural future

As Georgia’s government lurches towards authoritarianism, we head to Tbilisi to celebrate the city’s indomitable spirit and the passionate creatives striving to inspire hope for future generations

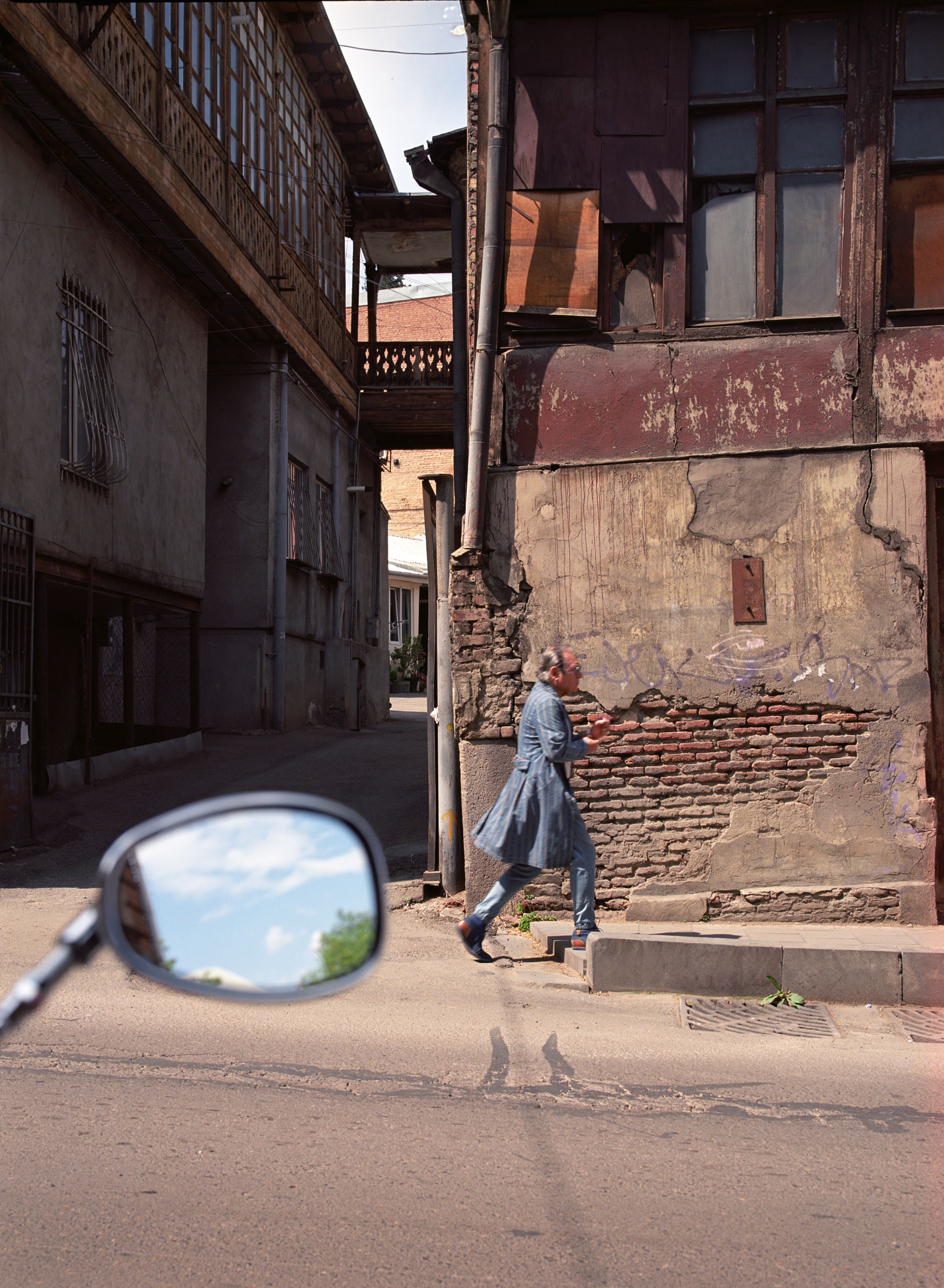

Tbilisi is simmering in the heat of high summer. Bark from the giant plane trees that line the leafier streets is peeling off the trunks in great slabs and shattering dramatically on the streets. Swallows are shrieking in the sky. The glare overhead casts surreal shadows that distort life below. The mood is oppressive and uncanny.

The feeling is matched by the political situation in Georgia at present, where the disputed ruling Georgian Dream party has introduced a raft of laws that signal an isolationist, regressive and anti-democratic stance, dismantling the country’s pending candidate status for EU membership. In the elections of October 2024, despite exit polls suggesting a coalition of opposition parties were set for victory, an outright majority was declared for the Georgian Dream party. After the election, pro-democracy protests outside the parliament buildings in Tbilisi were met with violence and tear gas. Members of the political opposition have been jailed on charges of corruption without trial.

Speak to people in the capital and they describe the cognitive dissonance of living under an authoritarian regime still masquerading as a functioning government. When the apparatus of democracy disintegrates, civic society is left suspended. The prevailing feeling is to keep going, head down, day by day, in the hope that Georgia’s long history and strong culture are more powerful than its current politics.

While Georgia may technically be young as a post-Soviet independent country in modern terms, its cultural history stretches back over five millennia. It is where the earliest evidence of winemaking and gold-mining has been found. Today, Georgian wine, food and hospitality are legendary. The country has its own beautiful script and sonorous language, and in 2001, Georgian polyphonic singing was designated by Unesco as a ‘masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity’. Tbilisi is known as ‘the immortal city’, not just because it is one of the world’s oldest urban settlements, but for its ability to withstand hardship.

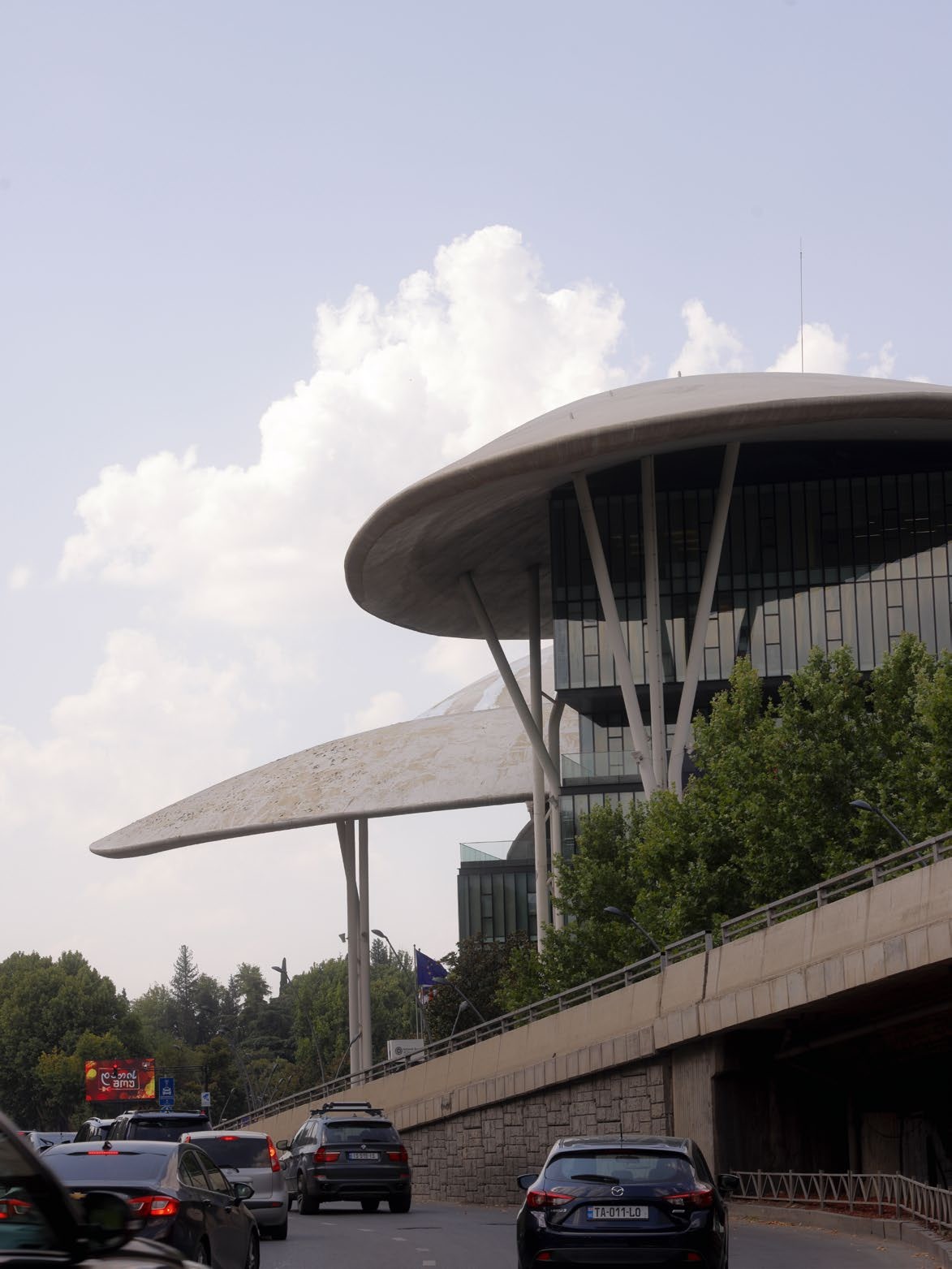

The 2012 House of Justice, designed by Massimiliano Fuksas

The Tbilisi TV Tower reflected in a glass façade

Its politics may be sinister at present, but Georgian culture is passionately independent. It has been safeguarded through periods of occupation and dissent, by a population that is fiercely proud of its cultural heritage. We visited Tbilisi 15 years ago, when former president Mikheil Saakashvili was in power, and busy dismantling the civil service in the name of progress. The mood then was febrile – with generations pitted against each other in a battle between preserving the past and forging the future. Tbilisi’s young creative community was ignited by this tension – called upon to define and redefine identity through art, design, food, architecture, music.

Fifteen years later, in a very different political reality, it is precisely this plucky and defiant cultural resilience that we set out to document in this portfolio (below). Each individual is a success story in their own right; together, they say something bigger about culture’s capacity to hold truth and inspire hope for future generations.

‘We can shout in the streets, or we can demonstrate our power with our hearts instead’

Traditional houses in Old Tbilisi

One of our featured cultural protagonists quotes the 19th-century composer Gustav Mahler: ‘Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire,’ by way of describing the collective mission to keep the flames of progress alive in Georgian culture for the nation’s youth. It’s a poetic and poignant call to arms. ‘We can shout in the streets,’ they say, ‘or we can demonstrate our power with our hearts instead.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

13 voices from Tbilisi’s cultural heart

Bellhop Hotel

The Bellhop team – from left to right, Nata Zarnadze, Anka Totibadze, Irakli Adamia and Beka Tolordava – photographed at the 12-room property’s restaurant Brød, where Japanese and Italian influences are sensitively layered rather than crassly fused. Cocktails are overseen by Adamia, who uses Georgian seasonal ingredients for his imaginative creations. There is a listening room and bar downstairs with a speakeasy vibe, and there are plans to open a bakery next door and a concept store across the street

Bellhop is a new hotel, run by childhood friends Nata Zarnadze and Anka Totibadze, which opened this summer in a former steel fabrication factory. It’s also a new type of hospitality in Tbilisi. ‘We are a neighbourhood hotel,’ explains Totibadze. ‘A place for locals and tourists together, designed by and for us. We wanted to make a place where we feel good, something for our friends and the community.’

‘Georgian hospitality is in everyone’s nature,’ says Zarnadze. ‘We like to please people – if someone crosses your door, you do everything to make them feel special. This attitude has played a huge part in our hiring strategy. Irakli Adamia’s cocktails are, honestly, some of the best in the world. Beka Tolordava remembers every guest’s name and order. We don’t just want to be good for Tbilisi or Georgia – we want to have an offer that matches what you find in New York, London or Paris.’

Totibadze, who worked for TBC, one of Georgia’s largest banks, for 20 years, chips in: ‘Hospitality is so important because you get to show who you are as a culture and country to guests. Tourism is one of the first sectors to be affected when the political climate goes awry. Ultimately, it is our job to do our best to make people feel good. If you don’t strive to be the best you can be, then you don’t grow – or survive, even.’ @bellhophotel

Gacha Bakradze and Lika Rigvava, nightclub co-founders

Gacha Bakradze and Lika Rigvava are pictured in Left Bank’s Space Two, a sequence of intimate rooms with a nightclub vibe. Used as a community space during the day, the adjoining Space One has board games, back issues of The Paris Review and former V&A exhibition catalogues alongside books on Alexander McQueen and John Soane, while the courtyard has a concrete ping pong table with an iron net

Left Bank is a nightclub that behaves more like a third space for Tbilisi’s cultural community. It was co-founded five years ago by music producer Gacha Bakradze and his partner Lika Rigvava, a former model who, pre-pandemic, walked runways at all four fashion weeks and worked with Jil Sander and Gucci. ‘We had the idea for somewhere like Left Bank for a long time,’ Rigvava says. ‘We wanted to create music nights that feel like a house party, where people can chat and play chess, and listen to music for as long as they like.’

Many describe the alchemy of Left Bank as somewhere fun and safe that generates its own sense of belonging. ‘It’s more than a party venue,’ Bakradze explains. ‘We have people aged 18-65 who come regularly. Though music is at our core, we also host book presentations, movie screenings and workshops. It attracts different crowds with shared values – when they’re here together, people feel present and time is suspended. The crowd becomes like an ecosystem.’

‘We wanted to create music nights that feel like a house party, where people can chat and play chess, and listen to music for as long as they like’

Lika Rigvava

‘There’s an unspoken code of conduct here,’ Rigvava adds. ‘When we opened during the pandemic, it was both the worst time and the best time. Face-covering rules were strict, but we flipped the message from one of control to mutual care and safety within the community. That safe sense of openness and togetherness is what makes Left Bank special.’ leftbank.club

Irakli Rusadze, fashion designer

Irakli Rusadze photographed in the courtyard of Gagetian House, an art nouveau building near his atelier in Tbilisi’s Chugureti neighbourhood

Growing up in Tbilisi, Irakli Rusadze was always interested in fashion and art. Instead of studying fashion formally, at 15 he started drawing and selling sketches to other designers in the city. He worked in garment factories learning how to pattern-cut and sew. In 2016, he launched Situationist, his own womenswear (and, more recently, menswear) brand at Tbilisi Fashion Week. Success came quickly. The Milan Fashion Federation invited him to show in the Italian city and, for the past five years, he has been part of the Paris Fashion Week calendar. Bella Hadid was one of his first clients, and he has dressed Kim Kardashian and Juliette Binoche. Three years ago, he was asked to make a dress for Beyoncé, and has since delivered 100 garments for the singer’s world tour.

‘Building a Georgian brand is hard, but we definitely have something to add’

Irakli Rusadze

‘When you are a Georgian brand, you have to try 100 times harder to be noticed compared to people emerging in Europe or America,’ Rusadze says. ‘We are a small team of 12, and are very hands on. Everything is done in our atelier – we take orders and then we produce, which is the best way to be efficient and sustainable in a very wasteful industry.

‘Building a Georgian brand is hard, but we definitely have something to add. Fashion needs big investment and our economic situation here is terrible, but I am fortunate to have had great luck. In 2021, [Comme de Garçons president] Adrian Joffe was in Tbilisi on holiday. He got in touch to arrange a meeting and bought several pieces from our archive for Dover Street Market.’ situationist.online

Gvantsa Jishkariani, artist and curator

Gvantsa Jishkariani is photographed at Eliava Bazaar, the dense and sprawling marketplace in the heart of Tbilisi, which began in the post-Soviet 1990s as a site for salvaging industrial materials and household goods. ‘The entire city is connected to Eliava,’ Jishkariani says. ‘It’s where everything comes to die and be reborn. It’s so male; to come here as a girl dressed like this is an act of rebellion, which I love’

Artist and curator Gvantsa Jishkariani has two galleries in Tbilisi: Patara and The Why Not. She graduated in architecture from the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts in 2013, and her multimedia work has been exhibited and collected by notable public institutions and private collectors worldwide.

‘My artwork is based on the clash of tradition and reality,’ Jishkariani says. ‘I am interested in heritage craft with cultural associations and symbolism such as mosaic, tapestry and feltwork. They are in my DNA and I hated them as a child, but through my work I make my peace by inverting their historical tropes.’ Mosaic work was a typical form of Soviet propaganda art. Jishkariani detaches political meaning in her mosaic work to explore narratives of a more escapist tone. Conversely, tapestries were traditionally decorative works in Georgia, and Jishkariani enjoys making political and satirical statements with her tapestry work.

‘I’m constantly in battle with the cultural ideas we have inherited,’ she says. ‘Tbilisi is mad and overwhelming: everything can be good and everything can be bad. You love it and hate it in equal measure. The layers of life, time and emotions are almost impossible to reconcile, but that tension is also what makes it such an extraordinary place.’ gvantsajishkariani.com

Shotiko Aptsiauri, artist

Shotiko Aptsiauri in his studio, in a former Coca-Cola factory in Tbilisi’s industrial Didube district

Shotiko Aptsiauri is one of Georgia’s most exciting artists from the younger post-Soviet generation. In his cavernous, dark-painted studio space, surrounded by empty paint tubes, cigarette packets and Coke cans (his studio is in a building complex that was formerly a Coca-Cola factory), Aptsiauri describes the power and predicament of being an artist in Tbilisi. ‘We have an opportunity to define our own contemporary artistic language here in Georgia, separate from our Christian and Soviet heritage,’ he says. ‘We are in an interesting place and time: I am a first-generation artist in a country that is still recently independent from Soviet rule. I feel a great responsibility to develop an artistic language that I haven’t seen before, which combines inherited knowledge with a belief in our future.’

‘The system hates artists; coming to the studio to paint each day, even lifting a brush, feels like a political act’

Shotiko Aptsiauri

Aptsiauri with his painting Waterless Swimming. ‘I was visiting Kutaisi [Georgia’s third city, to the west of the country],’ the artist says. ‘There was a swimming pool there with no water, the result of a breakdown in local infrastructure. The coach was teaching kids how to swim in the empty pool with arm gestures. It showed how humans can be resilient in a dysfunctional system, and it struck me as a perfect metaphor for our lives here in Georgia at present’

It’s a poignant remark that neatly captures the tension of the present political context. ‘There is zero support from our current government towards artists, and we are not allowed to receive funding from international bodies,’ Aptsiauri explains. ‘I am a painter by necessity, which might sound banal, but it’s a disturbing feeling. The system hates artists; coming to the studio to paint each day, even lifting a brush, feels like a political act.’ @shotikoaptsiauri

Kera Architects

Kote Gunia, Sandro Bakhtadze and Beka Gujejiani in their office, located in an old thermal power plant building overlooking the Left Bank club

Cousins Kote Gunia and Sandro Bakhtadze joined their friend Beka Gujejiani to form Kera in 2018, and the trio have a rock-star reputation among Tbilisi’s younger creatives. In Kera, they see Georgian architecture that is locally rooted and part of a global discourse. ‘Culture and context is everything,’ says Gunia. ‘We are concerned with reviving traditional knowledge, building techniques and material expertise, largely lost during 70 years of Soviet occupation, and translating this into a modern Georgian architectural language.’ Kera means ‘hearth’ in English, and the name refers to that primal idea of domestic inhabitation.

Kera (with Nana Zaalishvili, featured below) formed the Society of Georgian Architects earlier this year, with the aim of creating an organisation for knowledge sharing, and establishing regulations for better building practices. ‘We are a young country, in spite of our huge history,’ says Gujejiani. ‘Private property was non-existent in Soviet times, so different generations have differing understandings of what buildings mean and what architecture represents.’

Across the city, it’s evident there is an ongoing building boom. Former president Mikheil Saakashvili was enamoured with grand commissions by foreign architects, including Massimiliano Fuksas and Michele De Lucchi. Billboards and hoardings in Tbilisi show developers piling in, with little care or consideration for context or healthy urbanism. ‘Zero regulation leads to chaos,’ says Gunia.

‘There are pockets of optimism, though. A new architecture faculty at VAADS [the city’s art and design school] has an excellent programme and is inspiring a younger generation to value research and context. There is a small but growing interest in our rural architectural heritage, and examples of earth-building and workshops in vernacular materials and skills. Our ambition is to nurture a community of Georgian architects using design to revive and embed our cultural heritage for future generations.’ keraarch.ge

Lado Lomitashvili, designer

Lado Lomitashvili at Expo Georgia, with the prototype of a new aluminium candleholder he showed with design studio Jamieri at Collectible New York. Expo Georgia was built in the 1960s as Tbilisi’s main fairground. ‘I like it for its eclecticism,’ says Lomitashvili. ‘It’s a place for art, architecture and people to come together. The Soviet influence is heavy, but it’s part of our blood and story, so we need to adapt, assimilate and build a relationship with it on our own terms’

Lado Lomitashvili is a designer whose work sits somewhere between craft and art, product and interior design. His work is sold in collectible design galleries, but you might well find yourself sitting on his street furniture while in Tbilisi, too (outside Bellhop Hotel, for instance). ‘I describe myself as a contextual designer,’ Lomitashvili says.

After studying architecture at the State Academy of Arts in Tbilisi, he expanded his practice into art, before being accepted on to the master’s programme in contextual design at Design Academy Eindhoven in 2019. ‘Everything I do begins with asking why, before working out what and how,’ he says. ‘I work closely with different workshops in and around Tbilisi, understanding the material skills and potential of wood, iron and textiles, for instance, and bringing them together. It’s a literal way of using the fabric of the city to respond to a need. It matters to me that I build genuine relationships with these craftspeople and fabricators because this is a process of experiment and exchange, not a transactional service. I always bring them on the journey of what we are designing and making, and when they see the finished results and are proud and happy, it is the greatest compliment.’ @gypsandconcrete

Max Machaidze, artist

Max Machaidze is Tbilisi’s urban renaissance prince. He comes from a well-known family of artists, and his own expression finds form in rap, jewellery, interior and furniture design, as well as fashion and animation. The list goes on. He speaks in aphorisms with the lyrical fluidity of a philosopher or poet: ‘When I drink coffee, I’m a coffee drinker. When I’m singing, I’m a singer. One thing I don’t like is labels.’

Machaidze’s relationship with Tbilisi is symbiotic, combining angst and joy in equal measure: ‘Someone said that the dictionary is like a graveyard of words; until they are spoken, they are skeletons,’ he says. ‘The world comes to life when you interact with it and Tbilisi is the same – it’s like the corpse of an organism, it’s up to us and our actions to breathe life into it.

‘Culture is like a seed – when it goes underground, it blooms again’

Max Machaidze

‘I see everything as an open possibility. When you’re a kid, the world is a possible place; education is like a poison that you need to take to survive, and life after school is all about learning to be free again.’

Max Machaidze is wearing jewellery that he made from components found at scrapyards. He got his dragon tattoo three years ago. ‘It changes in meaning for me,’ he says. ‘Lately, it feels like a homage to my inner kid. When I was seven, I wanted to be an action figure that I could play with. I was an intense child’

Machaidze’s worldly effervescence is tempered somewhat by life’s harsher realities. ‘I went to my first demo aged 14,’ he says. ‘It shaped who I am. We have to work hard to breed hope, not sadness. Geopolitically, the world is fucked, not just Georgia. Culture is like a seed – when it goes underground, it blooms again.’ @llttffrr

Meriko Gubeladze, chef-restaurateur

Meriko Gubeladze at her first restaurant, Shavi Lomi, which opened 15 years ago. ‘We started with one gas stove, one fridge and no investment, but we made a commitment to using organic, local, seasonal ingredients. We are big on walnuts. If we had a national ingredient, it would probably be the walnut’

In a culture famed for its food and hospitality, chef-restaurateur Meriko Gubeladze is a modest pioneer. She has three restaurants in Tbilisi that are adored by locals and tourists alike. ‘I’ve been very lucky,’ she says. ‘All the women in my family are great cooks, and we grew up around food as a core part of coming together and reinforcing relationships. In Soviet times, there was no culture of going to restaurants – we ate at each other’s houses. My hope is that my restaurants have that feeling of home where people feel relaxed, welcome and special still.’

‘Food is a powerful repository of cultural identity. Restaurants are every bit as important for culture as museums and galleries’

Meriko Gubeladze

Making restaurants feel like home is not easy, but Gubeladze and her teams make it appear effortless. The food helps, of course – true to its reputation, Georgian food has to be tasted to be believed for the sheer breadth and quality of its ingredients. ‘We are a tiny country,’ says Gubeladze. ‘We have 14 different regions with a lot of geographical and climatic variation, so it’s a country of extraordinary contrast and diversity. Eating is understanding not just the ingredients but the culture and values of a country. Food is a powerful repository of cultural identity. Restaurants are every bit as important for culture as museums and galleries. They are safe places that encourage active participation. In return, they offer comfort, revelation or escapism, depending on what it is you’re after.’ @__meriko_

Nana Zaalishvili, architect

Nana Zaalishvili in front of the Bank of Georgia HQ, originally designed by George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania as the Ministry for Transport and Highways in 1975. Zaalishvili co-authored a book about Chakhava and has designed a collection of furniture, ‘Elements’, inspired by the building’s interlocking concrete volumes

Nana Zaalishvili founded her architecture studio IDAAF in 2016, but prior to this played bass in a punk band and edited an architecture magazine. ‘Like so many of our generation here, my work is research-based,’ she says. ‘The outcome of what I do is almost irrelevant. For me, it’s always about exploring, learning and responding. Architecture allows the greatest opportunity to go beyond a project, with legitimacy to explore archaeology, vernacular materials and forms.’

Prototypes of Zaalishvili’s modular adobe bricks, created by her practice IDAAF Architects as a response to environmental challenges

Zaalishvili travelled extensively throughout Georgia documenting Soviet bus stops, a project that spawned a book (published in 2018) that became an international bestseller. ‘Travelling opened my eyes to everything we have in this country that we weren’t taught about at school,’ she says. ‘Today it’s my mission to give shape to that knowledge for myself and others.’ Zaalishvili also teaches materials on the product design course at the School of Visual Art, Architecture and Design (VAADS).

‘We are a country of strong women; women don’t like to be victims’

Nana Zaalishvili

‘I am small but I feel powerful,’ says Zaalishvili. ‘My work has power and I have a big presence. I don’t feel threatened on a building site – I grew up with lots of male cousins. Georgia has always been a matriarchal country. We are a country of strong women; women don’t like to be victims. We are also a family of strong characters – my great-grandmother built her own house by hand from stone. We don’t wait for men to do things. I want to work in Georgia because I belong here and everything I do starts and ends here.’ idaafarchitects.com

Sofio Gongliashvili, designer

Sofio Gongliashvili learnt to knit in school and is wearing one of her cardigans in her portrait. In 2015, when floods decimated Tbilisi’s riverside zoo, she started knitting in earnest as a coping mechanism for the stress she felt. ‘I was showing my jewellery at Paris Fashion Week, wearing one of my cardigans,’ she says. ‘A Japanese buyer asked if I would make more knitwear for them to sell, and now I have three Japanese stockists’

Sofio Gongliashvili shares her Tbilisi home with her giant Rhodesian Ridgeback, Zimba, and her teenage twin daughters. Inside, it’s a little like stepping into a fantasy world – a fitting environment for the designer who has built a cult following with her exuberant oversized enamel jewellery.

‘I began making jewellery in the 1990s just before Soviet rule ended,’ she says. ‘There was no gas or light – it was a period of huge uncertainty, but I was very keen to learn a craft by way of finding a form of self-expression. Enamelware decorated with the cloisonné technique was traditionally used in religious settings and I enjoyed the bold, colourful possibilities of playing with iconography and symbolism, giving form to my own imagination.’

Jewellery by Sofio Gongliashvili

In 2014, Gongliashvili was invited to show her jewellery at London Fashion Week, and Sarah Mower (then head of the British Fashion Council) awarded her a prize, noting the extraordinary cultural specificity of her work. Today, Gongliashvili has a global audience and oversees a busy workshop with a team of five craftspeople.

‘My creativity comes from the strong feelings I have in response to the world around us,’ she explains. ‘For most of my career, we have not been in a peaceful state in Georgia. I do my best to convert the negative energy into optimism or fantasy through my work. I try to see everything as a fairy tale because I believe that all fairy tales have happy endings, and I hope the same will be true for Georgia.’ @sophogongliashvili

Sofia Tchkonia, cultural entrepreneur

Sofia Tchkonia’s father brought Coca-Cola to Georgia in 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union. She is photographed in the former Coca-Cola factory, now known as Factory Tbilisi. The vast art and culture hub can host events for up to 5,000 people

Sofia Tchkonia has a matriarchal sense of drive and duty to support Georgia’s future generations of creative talent. In 2015, she launched Tbilisi Fashion Week with the intention of platforming the nation’s fashion talent, but also bringing the global industry to the city. Around 80 buyers and journalists attended from America, Europe and Asia, and the event earned a reputation on the international circuit as a destination of intrigue and note. After a two-year hiatus, it will return in spring 2026.

‘Our fashion week is about much more than fashion design,’ she says. ‘I see it as a vital incubator for models, journalists and buyers, as well as designers. For young people, it’s an opportunity for self-expression. Fashion needs an ecosystem to flourish.’

‘When government support vanishes, it’s up to us to create an alternative model that keeps our culture alive’

Sofia Tchkonia

Tchkonia cuts a powerful presence in the vast halls of the former industrial buildings where the fashion week is held. She has bigger plans for them. ‘We have so many talented, creative young Georgians and a government that does nothing to support them,’ she says.

‘It’s understandable that they leave Georgia. We are turning these buildings into a school for around 450 students, for workshops and workspaces, a concert hall and a library to support the next generation of talent. The goal is to bring international talents here to teach so we establish real connections between Tbilisi and the rest of the world. When government support vanishes, it’s up to us to create an alternative model that keeps our culture alive.’ sofiatchkonia.com, factorytbilisi.com

Uta Bekaia, artist

Uta Bekaia (also pictured top of this article)

After studying industrial design at the Tbilisi Academy, Uta Bekaia moved to New York to pursue life as an artist, while designing costumes and sets for theatre. He returned to Tbilisi eight years ago with a principled purpose: ‘The tug of my roots in Georgia was strong and, as a queer person, I felt I could be someone visible that younger people could look up to at a time when we are an enemy of the state.’ An internationally renowned artist with an American passport, Bekaia feels a responsibility to speak out and represent queer youth. He is a founding member of Fungus, a platform for queer creatives across the Caucasus.

‘My queer art has its origins in Georgian traditions – there is nothing Western-influenced about it’

Uta Bekaia

His artistic practice combines craft and costume with storytelling and performance. ‘I am interested in resurrecting aspects of the pre-Christian, pagan culture of our country – finding fairy tales, myths and customs – and re-envisioning them through my personal lens into something ritualistic that speaks to our present reality,’ he says.

‘I find it empowering to work with my hands and my visual language is heavily inspired by folk culture. There’s an inherent queerness or otherness in so much folk, but it also has its roots in specific people and place.’

Bekaia notes this being particularly important at a time when LGBTQ rights have been dissolved by the government as a malign Western influence: ‘My queer art has its origins in Georgian traditions – there is nothing Western-influenced about it. The queer community is accused of being unnatural, but what could be more natural than folk culture?’ utabekaia.com

This article appears in the October 2025 Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Hugo is a design critic, curator and the co-founder of Bard, a gallery in Edinburgh dedicated to Scottish design and craft. A long-serving member of the Wallpaper* family, he has also been the design editor at Monocle and the brand director at Studioilse, Ilse Crawford's multi-faceted design studio. Today, Hugo wields his pen and opinions for a broad swathe of publications and panels. He has twice curated both the Object section of MIART (the Milan Contemporary Art Fair) and the Harewood House Biennial. He consults as a strategist and writer for clients ranging from Airbnb to Vitra, Ikea to Instagram, Erdem to The Goldsmith's Company. Hugo recently returned to the Wallpaper* fold to cover the parental leave of Rosa Bertoli as global design director, and is now serving as its design critic.