Dior offers a peak inside LVMH's cosmetics centre

Dior affords Wallpaper* an insider's tour of its high-tech travails at LVMH's Hélios centre in France's Cosmetic Valley

Image Group - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Edouard Mauvais-Jarvis was an ex-veterinarian studying pharmacology when he became fascinated by skincare. ‘People tend to believe that cosmetics are superfluous,” he says. “But cosmetics have an essential role to play in social relations. The skin of your face is the first thing that others see when we establish a personal connection.’ There is an evolutionary aspect, too—our initial impressions can attract us to a healthy person as a potential mate, or warn us away from an unhealthy one as a possible carrier of disease.

As France gradually reopened after the COVID-19 lockdown last spring, Mauvais-Jarvis, Dior International’s Scientific and Environmental Director, took Wallpaper* on a tour of Hélios, the state-of-the-art centre where LVMH, Dior’s parent company, conducts research, creates and innovates around perfumes and cosmetics for some 14 different brands. Dior is the luxury group’s biggest beauty brand, and represents a whopping 70 percent of the centre’s activity.

Inaugurated in 2013 in St-Jean-de-Braye, near Orléans, Hélios is part of Cosmetic Valley, one of France’s so-called “competitiveness clusters” (a geographic area bringing together businesses, research centres, suppliers, etc., working in the same sector). Nestled in a grassy thumbprint surrounded by trees, the building is located on a 55-hectare production site for Parfums Christian Dior. The French architectural firm Arte Charpentier designed the 18,000 sq m structure as a three-story equilateral triangle around a central atrium. True to its name, the nearly all-white building is filled with natural light, which enters through a roof made of semi-transparent ETFE (fluorine-based plastic) cushions that modulate the internal temperature. Soft edges and a façade of white screenprinted glass help the building to merge into the landscape.

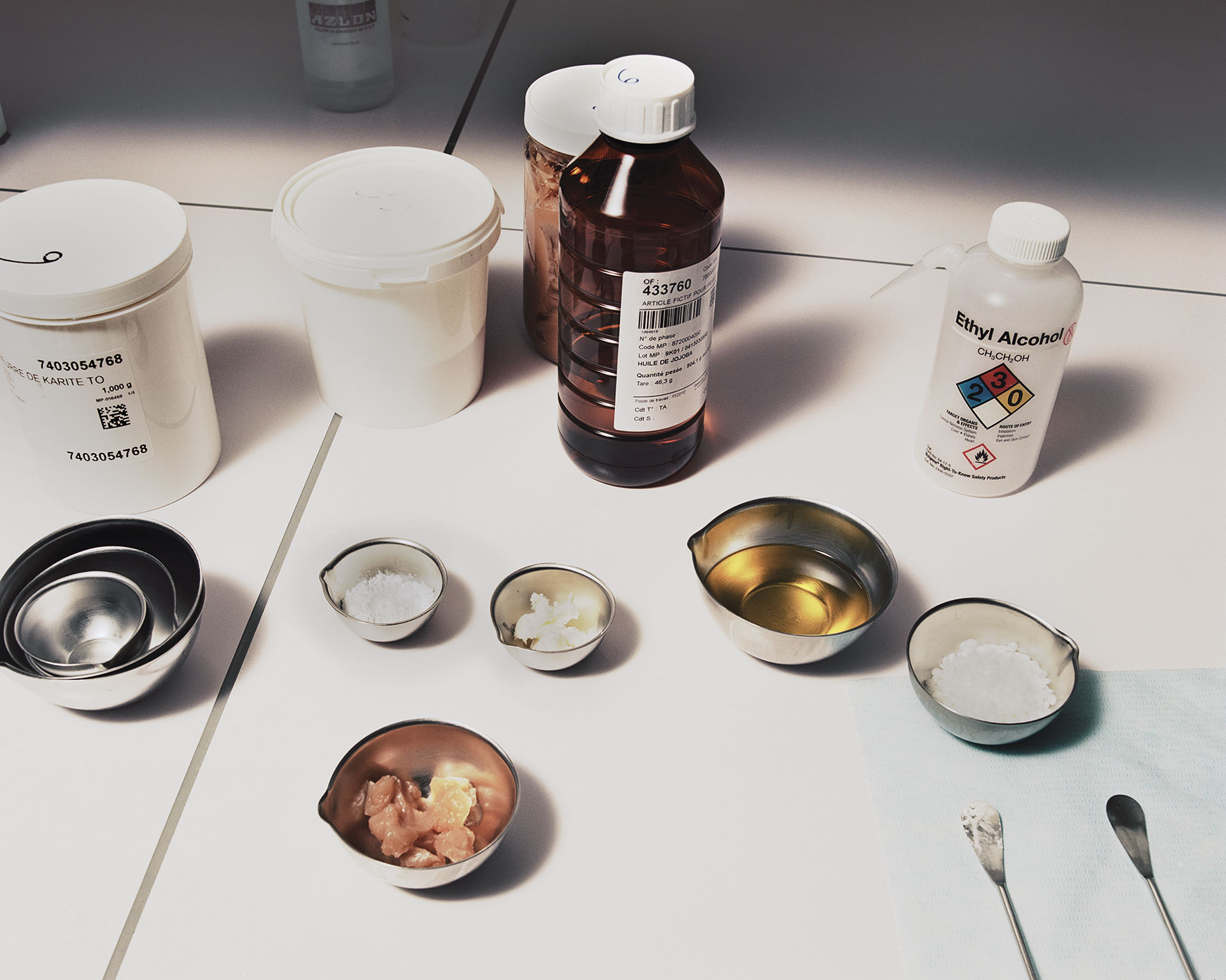

A researcher whips up a sunscreen emulsion. Right, materials used by researchers at Hélios, whose work spans skincare, cosmetic, and fragrance development

Inside Hélios, some 350 researchers work on different stages of R&D. Laboratories line each side of the triangle, their windows offering views of atrium and forest. Mauvais-Jarvis takes us to see one devoted to skincare formulation, where a counter is set with glass jars containing dried flower buds, powders and extracts. He points out an extract of Rose de Granville, a seventh-generation hybrid descended from a wild rose that grows on the cliffs of Normandy, bravely resisting salt air and ocean winds. Hélios’ researchers have isolated eight unique molecules from the hardy rose as active ingredients for Dior Prestige’s new Micro-Huile de Rose Advanced Serum.

Nearby, a scientist in a white lab coat is using a contraption resembling a kitchen mixer to whip up a smooth white emulsion for a sunscreen. Beyond her, the contents of the lab are strictly off-limits to visitors, including creams lined up on the windowsill to see how they react to the natural light of a hypothetical customer’s bathroom.

If Hélios is wary of outsiders seeing its secrets, it is because the stakes are extremely high. France dominates the global cosmetics industry, controlling nearly one-quarter of market share. A major reason for this preeminence is its investment in R&D—according to a 2019 report by the consultancy Asterès, the French cosmetics industry spends two percent of annual turnover on innovation. For big groups such as LVMH, this investment rises to three percent.

When asked what sets Hélios apart from other research centres in Cosmetic Valley, Mauvais-Jarvis responds, ‘Our R&D covers a spectrum of disciplines integrated in a single building, which is exceptional.’ Botanists, chemists, biologists and other experts all work side by side, specializing in more than 20 scientific fields, including ethnobotany, physical chemistry, powder formulation, delivery systems, sensory analysis, toxicology and cell biology.

One example of this range is Dior’s work in the past few years with a neuroscientist from the University of Tours, testing how changes in the skin affect our perception of a person’s age. Their research found that our brain determines the apparent age of another person in less than 100 milliseconds, based on visible signals of health in the skin, such as tone, radiance and texture. ‘The impact of these signs on apparent age can be even greater than that of wrinkles,’ Mauvais-Jarvis says. Using A.I. and machine learning, Dior then created a database of faces, teaching the computer to evaluate age in the same way the human brain does, and measuring the relationship between visible indicators of health and perceived youthfulness.

The 18,000 sq m Hélios R&D centre, designed by architects Arte Charpentier and opened in 2013, brings together all of LVMH's research teams

The researchers found that the skin’s signs of good health (or lack thereof) can make a 43-year-old look as young as 38 or as old as 49. Mauvais-Jarvis says that Dior is using this information to make products that target wrinkles and firmness but also ‘focus on corrections that might seem minor but have a huge impact on appearance and perception.’

For the past two decades, Dior has also been conducting research into stem cells, the only cells that can endlessly self-renew and rejuvenate the skin. In 2018, Dior Science made the surprising discovery that stem cells do not decrease in number over time. Instead, they lose their energy potential. The finding was impressive enough that Dior Science subsequently signed a research partnership with the CiRA Laboratory at Kyoto University, directed by Nobel Prize-winner and stem cell specialist Shinya Yamanaka. “We are very flattered to have them as a partner,’ says Mauvais-Jarvis. “Their interest in working with us attests to the quality of our scientific research.’ Floral science is another one of Dior’s specialities, going back more than five decades. Plants contain a wealth of powerful molecules, and scientists have only started to scratch the surface of their cosmetic and therapeutic properties. Over the past 25 years, Dior has planted eight flower gardens around the world, all organic or as close to organic as possible.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A laboratory at Hélios analyses the flowers, and has developed its own customised methods for extracting individual molecules, which Mauvais-Jarvis says represent 60-80 percent of Dior’s active ingredients. ‘We cultivate particular flowers in a specific way, harvest them at a specific time and use our own extraction techniques, to develop something that is very high quality and difficult to copy.’ It was after screening nearly 1,700 flower ingredients for their ability to reboot tired stem cells that ethnobotanists selected four particularly vigorous varieties for a new formulation of Dior’s Capture Totale C.E.L.L. Energy anti-age cream and serum: Madagascan Longoza (which can even grow on burnt land), Chinese Peony, White Lily, and Chinese Jasmine. The entire new Capture Totale range contains, on average, 84 percent natural ingredients, as sustainability has become a key subject for Dior. A laboratory at Hélios is dedicated to making its formulas as natural as possible and removing any suspect or non-biodegradable ingredients. Dior’s packaging has evolved, as well—plastic bottles are being replaced with glass, outside packaging is made with recyclable FSC cardboard, and packaging volume has decreased by as much as 30 percent. As Mauvais-Jarvis points out, ‘You can have the cleanest formulas in the world, but with dirty packaging they are useless.’He underlines that it has been a Herculean task to reformulate Dior’s existing products and recipes while maintaining their performance and sensoriality—the same scent, consistency, glide, etc. He compares the challenge to ‘making a meringue without eggs.” And yet it is vital to get it right: “You use a skincare product for a long time. If there is no sensory pleasure, people will stop using it after a week.’ Science has taken skincare and makeup a long way since ancient Egyptians wore eyeliner made with lead and Renaissance Italians used mercury sulfite as blush. ‘There is a reason people have used cosmetics for millennia,’ says Mauvais-Jarvis. ‘By putting something on the skin, we can improve our appearance. For a long time, the approach was empirical. You applied something, and if it did something, great. Then, little by little, we began to understand how and why it worked.’

INFORMATION

dior.com

As originally featured in the September 2020 issue of Wallpaper*

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.

- Image Group - PhotographyPhotographer