Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The consummate Italian creative multitasker, Piero Fornasetti, started his career as a painter before plunging into the design and decoration of furniture, interiors, scarves and everyday objects as banal (yet fundamental) as trash cans, ashtrays and umbrella stands. His fantasy-driven flair for drawing, painting and sketching was central to his development as a designer. In fact he was a pioneer, in the 1930s, of elevating ornamentation to the loftier, structural element of design.

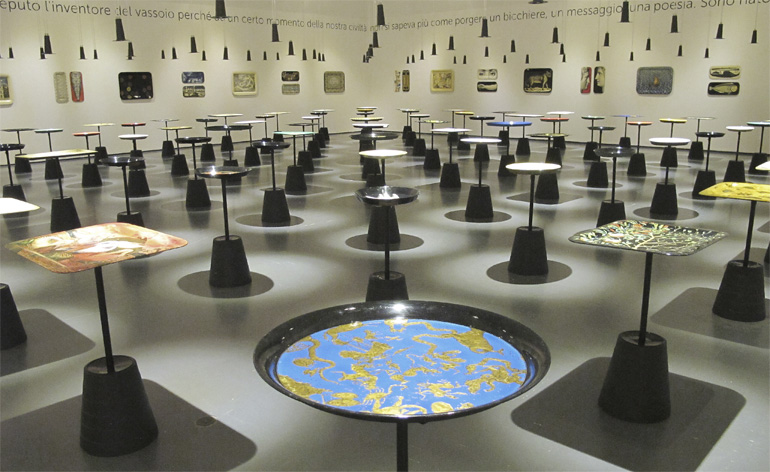

The idea crystallised at his studio and production centre in central Milan, where Fornasetti designed, printed and hand-painted his signature black-ink lithographs before applying them to the metal and wood objects - which he also produced. The span of his prolific creative output has now been consolidated for the first time in an impressive new exhibit of more than 1,000 pieces at Milan’s Triennale Design Museum. '100 Years of Practical Madness', designed and curated by Fornasetti’s son, Barnaba, honours the Milanese designer who would have turned 100 this year.

We spoke with Barnaba Fornasetti in Milan to find out more about his father's ever-enduring design legacy...

Why now for a Milan exhibit?

To be honest, it’s been a lifetime that we’ve been trying to organise a Fornasetti exhibit in Milan and there was never a concrete reaction by an institution here. It’s one of those Italian mysteries. Finally with the Triennale, the moment arrived.

As the exhibition's designer, how have you organised the space?

The entryway is dedicated to his work in Milan. There are antique photos showing interiors he created: a pastry shop near the Duomo, the Rinascente department store, a cinema, a police barracks - he frescoed the walls during the war so he wouldn’t be sent away. The only one of these structures that still remains today is the Hotel Duomo.

Explain the first main room.

Here are all of the things that inspired him, the point of his departure. He began with antique books, old prints and images of the past. He was a wonderful designer and could sketch hands and faces very well. But he stole a lot of images from others and he reused them.

Where did he find the face of the woman he used so frequently?

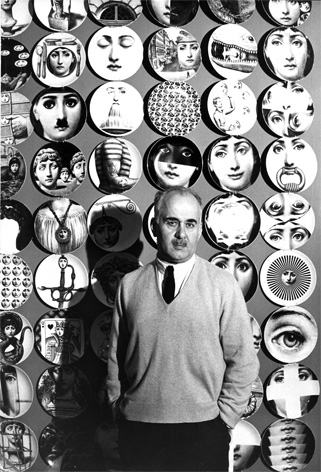

The portrait of Lina Cavalieri was a print he found in an old book. He stole an antique image from the century before, but he made 300 variations on it over the years and created an icon. It became an enormous source of recognition for him and for his work.

What was the first piece of furniture that he designed?

A cabinet in the 1940s. Here you see the three front cupboard doors of that piece. It looks like a collage of letters and clippings from books but every single thing was painted by hand. Every word, even the texture of the walnut wood, was painted. After this, he created a system of printing of lithographs, so that the ink outlines could be copied and then were painted in colour by hand to speed up the process.

Tell us about his studio and what took place there.

His studio was first used for painting, then he became a printmaker and then a producer of objects. Aside from being a genius artist with a flair for fantasy, he was also extremely deft in the technical printing process. Fontana, de Chirico, Campigli, Sassi, Clerici, Caratta, they all came to his studio to print art books, lithographs, limited numbers of art. So he was also a sort of publisher, too. Having all of these artistic personalities around gave him a huge amount of stimulation and inspiration for his own work. When you look at his work you see the influence of so many different artists, from the realists to the metaphysicists to 'Natura Morta' by Morandi.

When did he meet Gio Ponti?

My father had designed a series of printed silk scarves that was presented in a competition held at the Triennale in 1933. Ponti saw them and said, 'Aside from being a great printer, you’re also a great designer. Let’s collaborate on something.' So they began to work on techniques of putting art on everyday objects. But the industry hadn’t really started; they were too modern and anti-conformist. So in the end my father decided to produce the objects himself. He created his company to do that.

What specific projects did Fornasetti and Ponti work on together?

The interiors of several luxury apartments, the Andrea Doria ocean liner and several movie theatres in Milan.

Are there items in the exhibit that have never been seen before?

Yes, several of the designs, paintings and the huge cabinet designed with Ponti, for example. All of it was in the archive.

You’ve also included new items...

I’ve tried to keep a contemporary link. So these furniture pieces are ones I designed myself using old pieces of wood from the lithographs. They were used to print the decorations and prints. They were not usable anymore, so I decided to create a collection of furniture and accessories used with the original zinc plates. It’s a kind of recycling.

What plans do you have for the exhibit after Milan?

We’d like to send it around the world. For years now Milan has been only an importer of exhibitions from other countries. So I believe it’s important that this [exhibition] was born here, the capital of design, and can be exported to other cities later.

Nearly one hundred trays varying in shape and decoration take pride of place in this room

The third room features many of the paintings made by Fornasetti over the course of his life. The display case in the foreground, meanwhile, houses an array of ashtrays, boxes and books

Fornasetti's 'Valigie' umbrella stand is presented in front of the 'Chiavi segrete' (secret keys) wallpaper produced by Cole & Son

From left: 'Strumenti musicali' (musical instruments) table top; 'Cammei' obelisk lamp, mid-1950s; 'Conchiglie' chandelier, hand-made by his wife Giulia using real shells for their house in Varenna on Como Lake; 'Strumenti musicali' chair, 1951; 'Octagonal Mirror'; 'Sole' chairx, 1950s; 'Interno armadio' screen, 1950; brass coat hanger, 1970s; and Piero Fornasetti’s own 'Arlecchino' silk waistcoat Arlecchino, from the 1940s

A vitrine of Fornasetti's curios demonstrates the designer's boundless imagination

Several porcelain plates from one of Fornasetti's most well-known series 'Tema e Variazioni' (theme and variations) are strung across white sheets arching over the gallery space

The monochrome 'Women’s bicycle', 1980s, with leather furnishings hangs above the space

'Obelischi' silk scarf, by Piero Fornasetti, 1939

The 'Lux Gstaad' chair (left), by Barnaba Fornasetti, 2009, and 'Musicale' chair (right), by Piero Fornasetti, 1951

A side table decorated with a variety of sea creatures is an example of how Piero Fornasetti infused art into everyday objects

No surface was out of reach for Fornasetti, who transferred his black and white lithographs onto a plethora of furnishings

A detail of the corridor lined with several cylindrical umbrella stands

'Braccio con bicchiere' tray (above) and 'Marameo' tray (below)

'Duomo Sommerso' depicts the Duomo di Milano submerged underwater on a folding screen

Fornasetti's self-portrait shares exhibition space with the 'Moro' chair, on which a Moorish character is painted

Collections of work from the Fornasetti atelier crowd the exhibition space, neatly grouped by theme: the 'Oggetti con nastro' magazine rack containing pieces from Fornasetti's print archive; 'Ultime notizie' hand-coloured silk pours out of a press imaged on the wall; and lithography proofs printed by Piero Fornasetti for other famous Italian painters like Giorgio De Chirico and Lucio Fontana hang in a cluster

A door to Melchiorre Bega’s architecture firm (far left), made from acid-etched glass and brass, sits between two rooms in the exhibition

Former display samples of table tops (left) from Fornasetti's Milan showroom run along one wall, displayed alongside the designer's 'Angolo spogliatoio' screen, 1955 (right)

Piero Fornasetti stands in front of a wall of plates from the 'Tema e Variazioni' series.

ADDRESS

La Triennale di Milano

Viale Emilio Alemagna, 6

20121 Milan

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

JJ Martin