King Castle: remembering Wendell Castle, as we knew him, in his upstate New York home

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Art furniture pioneer Wendell Castle passed away on 20 January 2018. The following is an article originally featured in the December 2009 issue of Wallpaper* (W*129).

Hurtling past a Currier & Ives landscape, windshield-wipers working overtime, the car gladly pulls up to the kind of countrified homestead not generally associated with sleek fibreglass furniture inspired by molar teeth and black widow spiders. Back in 1905, when electricity was the big headline in home design, a wealthy wheat farmer built this estate in Scottsville, on the hemline of Rochester in upstate New York, just as America’s Midwest sprouted its own amber waves of grain and gradually stole away the business. Now, more than a century later, to stroll the house and grounds is to surrender to the ultra-modern surrealist impulses of Wendell Castle, a midwestern émigré who is the property’s unlikeliest caretaker and renovator.

Artist in residence at the Rochester Institute of Technology, Castle is more globally celebrated as an American craft-movement elder early to the concept of art furniture. In the late 1960s, he pioneered hot rod-hued plastics and gloopy biomorphic chairs, tables and desks that have a presence in the permanent collections of all the majors. Now 77, Castle remains one of the first iconic art-furniture brands, signing his pieces as any self-respecting artist would, with a Dremel tool – a sort of hillbilly cousin to a dental drill. He has lived long enough to see the masses slowly educating themselves into the ranks of the cognoscenti. One used to have to be a decorator or an architect to buy from Knoll. Not any more. Not in an era where the gods of mod are designing can-openers for the big chain stores. Of course, some of what passes for high design these days verges on comedy: ‘These houses where you push a button and every light in the house will come on, or you need to push the TV screen to get the lights to go on... I don’t see anything wrong with just flipping a switch,’ says Castle.

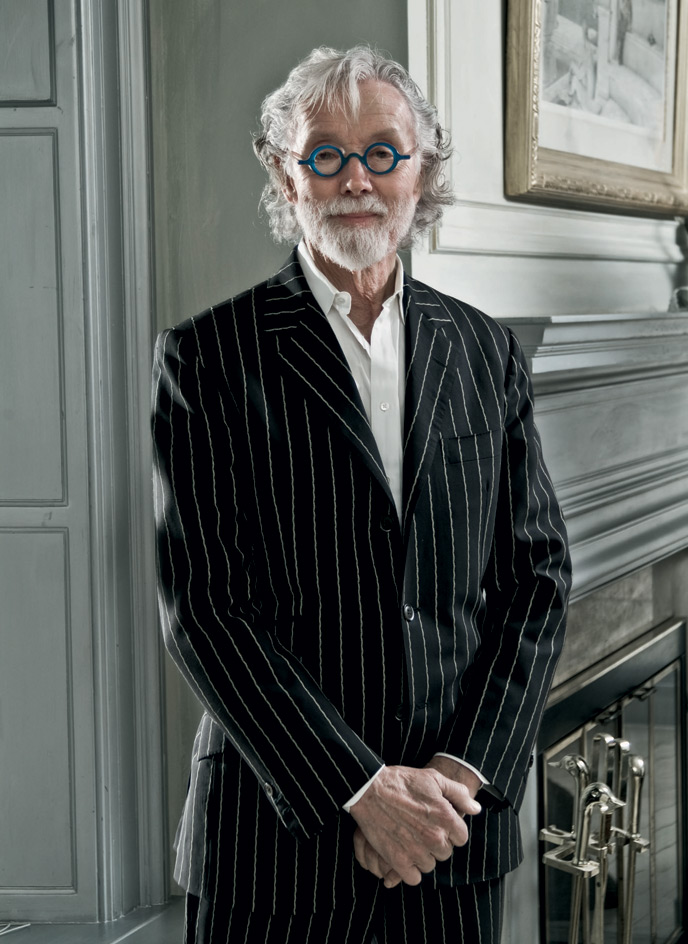

The wise-old beard and Le Corbusian goggles, custom-made in Paris, both project a certain priestliness, but Castle was never such a high-minded renunciant that he didn’t demand – and receive – masterpiece prices. ‘Certainly, in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, I got more money than anyone else,’ he says. Now, it’s Marc Newson who scores the repetitive zeroes on the cheques. Most recently, he has been in discussion with architect Peter Marino to make a gold-leaf bench for a client. And the older pieces have steadily appreciated; last year, one of his chairs sold at auction for $204,000. People are asking again about those fibreglass toothpaste-squeeze lamps that didn’t sell 30 years ago; luckily, the moulds were still alive in the weeds in his backyard, and another edition is in the works.

The living room furniture includes a 1970s chair and sofa, and a 1960s coffee table, all by Castle, while two of Jurs’ sculptures are perched on the mantlepiece

This afternoon, a pelting rain has threatened plans for a leisurely game of croquet, so Castle and his briskly attractive sculptor wife Nancy Jurs are in the living room waiting for the weather to pass. If not, there’s a ping-pong table casually sharing footage with a gangly pair of Castle’s ‘Back Widow’ chairs, a magenta ‘Osbourne’ coffee table, and a pair of Jurs’ samurai torsos. Surrealist surprises are strewn hither and yon – a tempera-bleached ‘tea party’ atop a radiator, an outdoor human-scale chess-game installation (World Piece, 2008, by Jurs) just off the porch. A spring-fed koi lake scooped out of one side of the property apparently functions as the family swimming pool. ‘The koi all have nams,’ says Jurs. ‘We buy them at PetSmart and feed them old dried bread and cereal.’ At the point in the tour, one half expects those croquet balls to be live hedgehogs; the mallets, live flamingoes.

Not long ago, the hobbity kitchen was renovated and rigged so that two cooks could do their thing simultaneously at the Gaggenau burners and a pair of mushroom-cap butcher-block islands. Jurs is a vegetarian. Castle is not. But otherwise, Castle and Jurs are boon collaborators, their works sitting side by side in the home. In the living room is yet another enigmatic artwork. ‘I was staying in a hotel about ten years ago,’ says Jurs, ‘and the art on the walls was so terrible, I said, “Wendell, I cannot sleep.”’ So she flipped it over, ‘and it was a revelation. I had all kinds of bad art in frames, so I turned it all around and painted the canvas backs silver.’

There was no art in Castle’s small-town Kansas home. His parents, a vocational agriculture instructor and a grade-school teacher, couldn’t be bothered to save any of his drawings. They wanted him to study business – ‘something that would be respectable,’ he remembers. A younger brother became a Methodist minister. ‘That was fine. They loved that,’ Castle recalls with some edge in his voice. A chance encounter with an issue of Poplar Mechanics that was lying around the house turned him on to duck decoys made from stack-laminated wood, an image that the child’s mind filed for later reference.

This spinal and rosewood oak music stand, made in 1964, is perhaps Castle’s most recognisable piece. On the stairs are his old English croquet mallets

In the era of Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson, Castle took a degree in industrial design at the University of Kansas. A room-mate looking to become an astronaut suggested the Radiation Corporation of Florida hire Castle to design the interiors for a putative moon base. ‘It was ridiculous,’ he recalls. ‘The guy who was running it was a German scientist who I always thought was maybe a fraud. It was just total guesswork, informed by the movies.’ Then it was back to school to train as a sculptor, an obligatory bounce through New York City, ‘which didn't work out the way I wanted’, says Castle. ‘I couldn’t afford studio space except in Brooklyn just off Ocean Parkway.’ When Rochester Institute of Technology recruited him for its nascent furniture programme, he went because (frankly) he needed the money.

‘Tell the truth, Wendell!’ says his wife. ‘He got here, and he told other people – not just me – “Oh God, I hate this place.”’ But after two years, country life suited him; the 25 acres he eventually secured as a home – the ancient soya bean-factory studio a half-mile up the road – was a vast improvement over anything Ocean Parkway had to offer. Furniture could be sculpture, and Castle felt the field was wide open. ‘I could make some impression here,’ he remembers thinking.

When did he know he had made some impression? When after a reasonable success, he had tagged along on a visit to master carpenter George Nakashima’s studio with colleague Sam Maloof (aka the ‘Hemingway of Hardwood’), and Nakashima pretended he had never heard of one Wendell Castle. Such are this world’s sequoia-size egos.

A Julie Williams painting hangs above a ‘Samba’ cabinet with leather drawer handles, from the Wendell Castle Collection. The floor light was made by Castle in the 1960s

Back in his own studio, Castle wields a chainsaw as routinely as a drafting-table pencil. By now, he has learned that exotics like zebra wood and bubinga are overrated. ‘It’s the form that’s more important, and if the wood has too much character, it can distract from the form.’

Two of his most valued employees are body-shop alumni who have worked on hot-rod cars, and he depends on their skill at applying the several signature coatings of iridescent automobile-grade urethane paint. Castle appreciates the musculature of classic cars and is doubtlessly the only academic in the region streaking past the sagging barns and solos in his slant-nosed Porsche 911 Turbo or his 1970 Jaguar E-type convertible, parked in the garage next to his wife’s John Deere Gator. A rare Nash-Healey, the first American sports car made after the Great Depression, is somewhere in the throes of restoration.

‘I like oddball,’ Castle admits. ‘I really haven’t had the money to buy million-dollar cars. I mean, Marc Newson can buy a million-dollar car – which he’s done.’ One senses Newson’s headlights glowing challengingly in Castle’s rear-view mirror. Castle’s daughter, an editor for Taschen who lives in Paris, is doing a book on Newson. There is some fascination with the Newson studio’s versatility, its ability to rethink restaurants, watches or a line of hoodies for G-Star Raw.

On the landing, the aluminium ‘Zombie Too’ light,

Castle admits he still spends most of his time thinking about chairs, and though he’d love to try newly voguish rapid prototyping – feed a photograph into a machine that then promises to laser out something cool – he doesn’t buy into the hysteria surrounding such NASA-novelty materials as titanium or carbon fibre. A torchère can look fabulous in simple poplar. ‘It really doesn’t seem to make so much difference what it’s made out of,’ he says. ‘A fibreglass chair used to be a cheap chair. Well, it really isn’t any more. If you made a chair out of concrete, which I am working on now, does that make a cheap chair? Not necessarily.’ As for the ‘Black Widow’ chairs, ‘they’re not the most comfortable,’ Castle freely allows. But they won’t hurt you, either.

Would he have liked to live in a modern house, all high cheekbones and minimal make-up? Well: Sure. But original mantels and mouldings painted in an automotive silvery grey go surprisingly well with his life’s work. Castle grabs a ukulele off an ash chest, the ‘Samba’ cabinet, part of the Wendell Castle Collection manufactured by Icon Design, ‘Ain’t she sweet?’ he strums, bursting into song with considerable brio.

Castle’s most recognisable piece is perhaps the rosewood-and-oak music stand in the corner. He has also designed five Steinway pianos and would love to do a sixth, encased in fibreglass, material he has only recently come back to after a 40-year hiatus. And he would probably want to do it in a vivid automotive colour. Maybe some rock star would buy it.

Asked, ‘What’s ugly?’ Castle thinks for a few seconds. ‘Well, ugly to me isn’t necessarily a bad word. I kind of like ugly. Beautiful might be the least interesting.’ He knows he doesn’t want to be designing can-openers any time soon. Or hoodies, for that matter. That kind of immortality doesn’t interest him. Suddenly, he’s feeling a chill. He reaches past the duck-headed fireplace tools and shuts the window as the rain beats on.

As originally featured in the December 2009 issue of Wallpaper* (W*129)

Wendell Castle, 77, pictured in his living room. He began teaching the Rochester Institute of Technology’s furniture programme in the 1960s and is now artist in residence

Fozzie the dog in the hallway, in front of an installation that featured in Jurs’ ‘Déjà Vu’ exhibition at Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, in 2009

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Wendell Castle website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.