Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa

‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, celebrates the 20th-century photographer

In April 2024, curator and author Catherine E McKinley travelled to Mali to meet the family of legendary photographer Seydou Keïta, to discuss an upcoming exhibition and to ask for their participation.

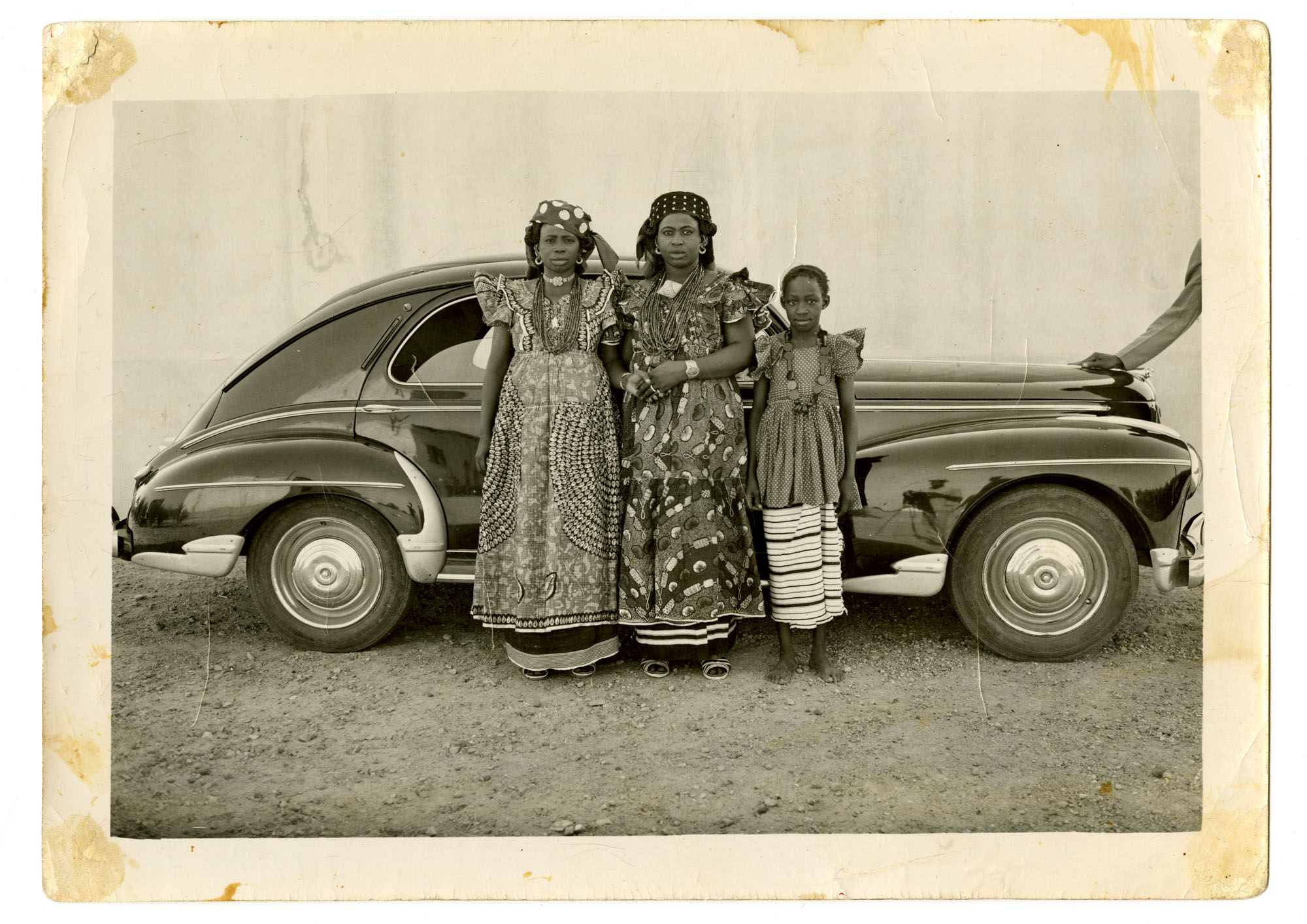

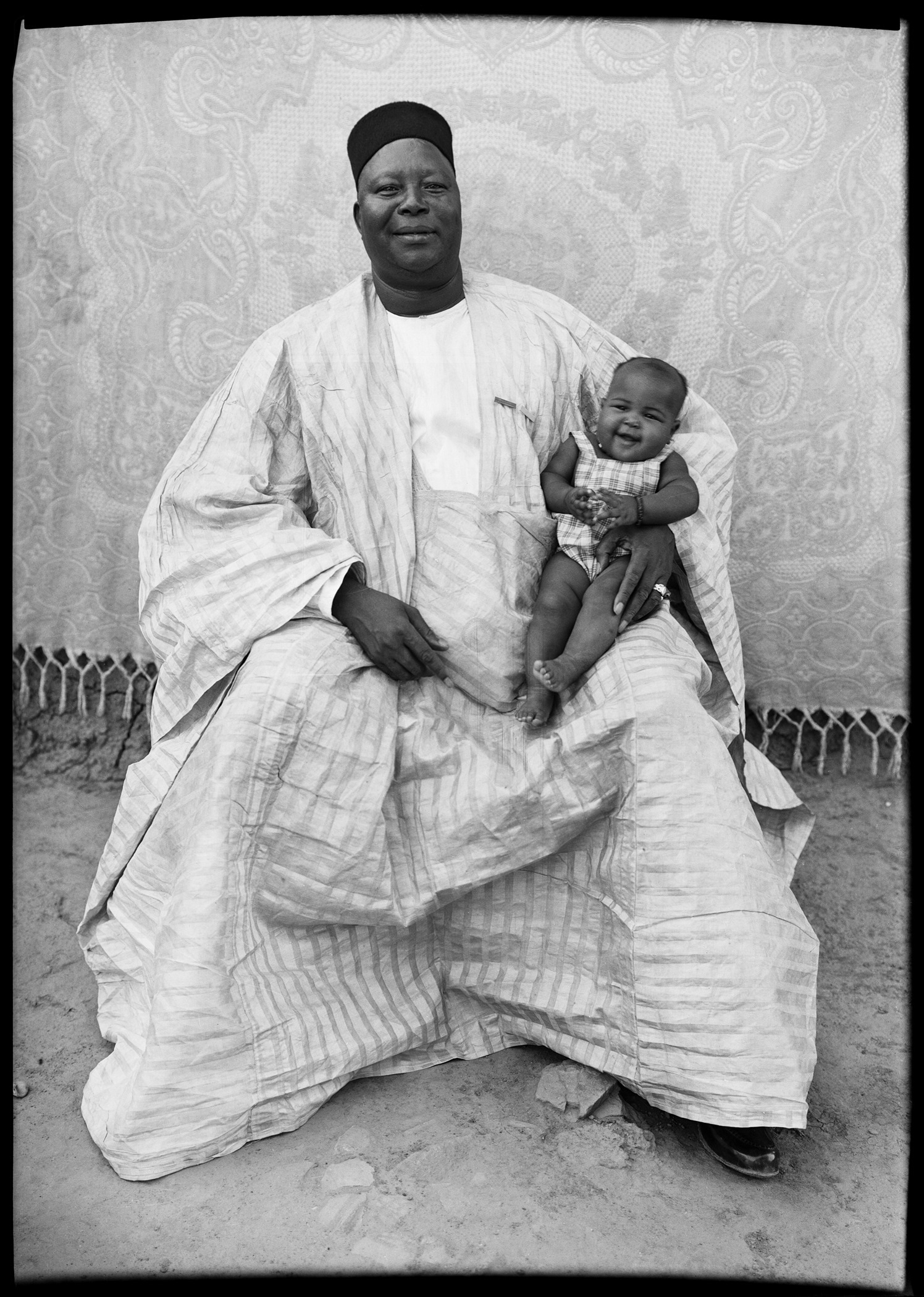

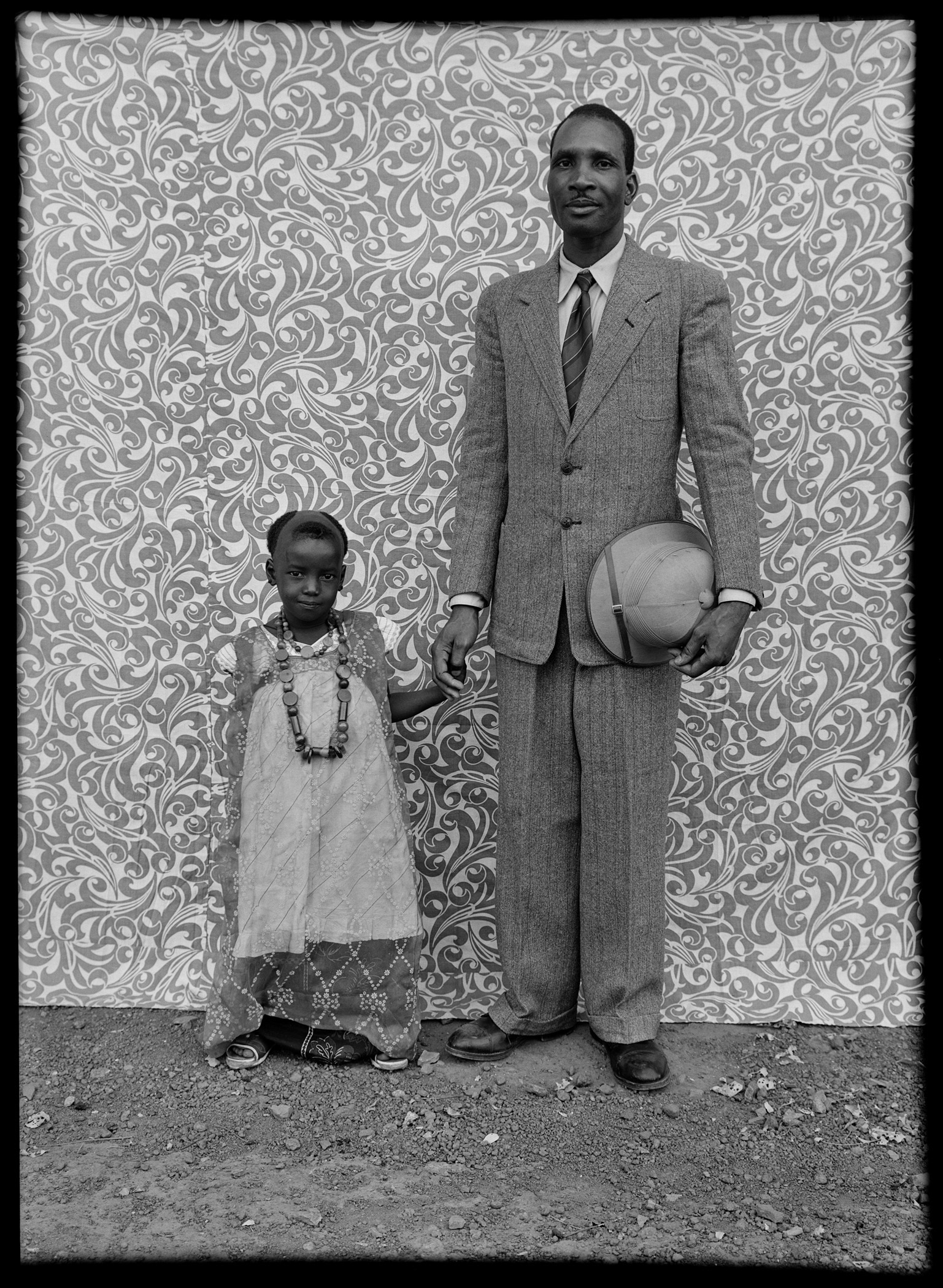

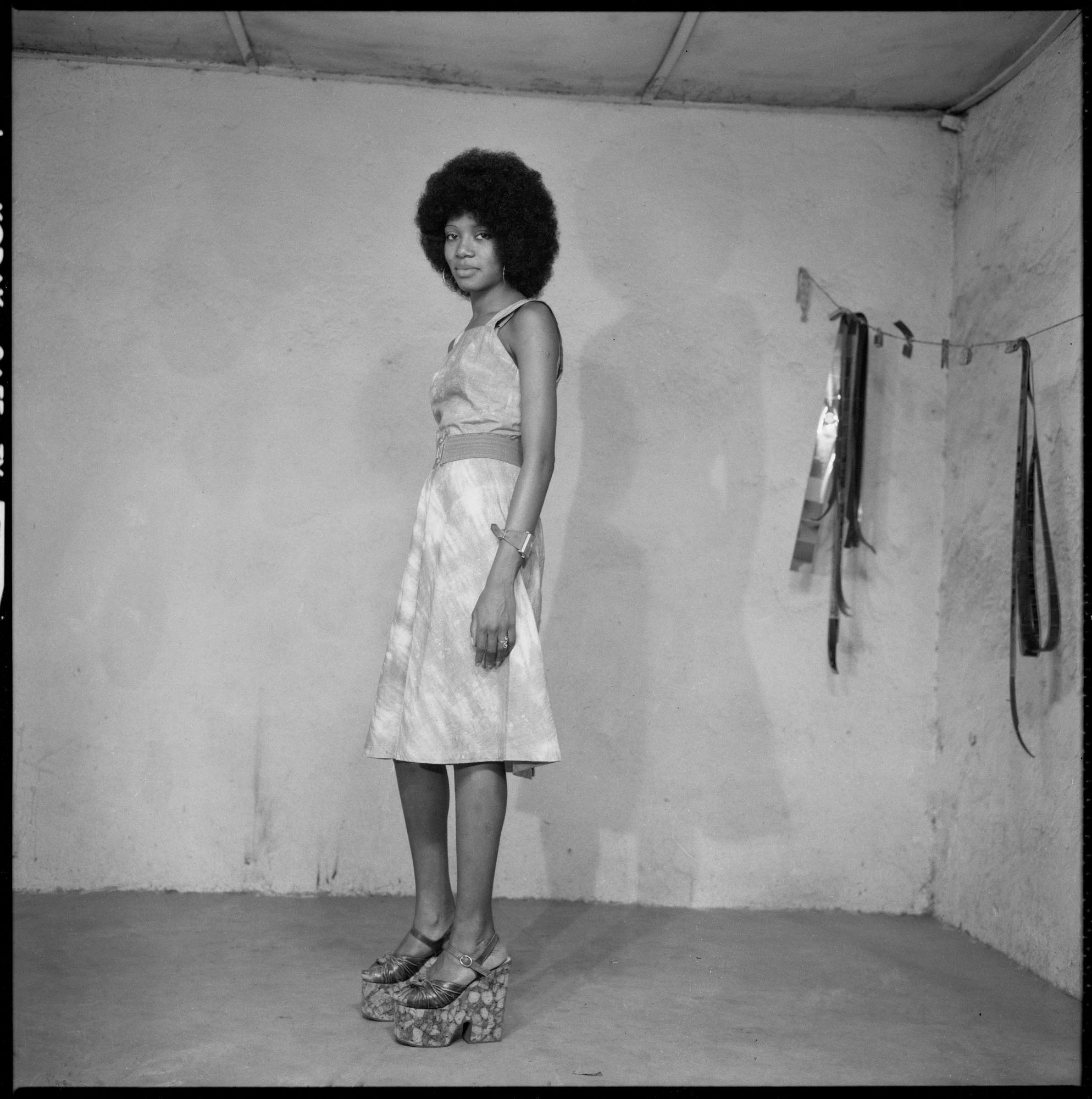

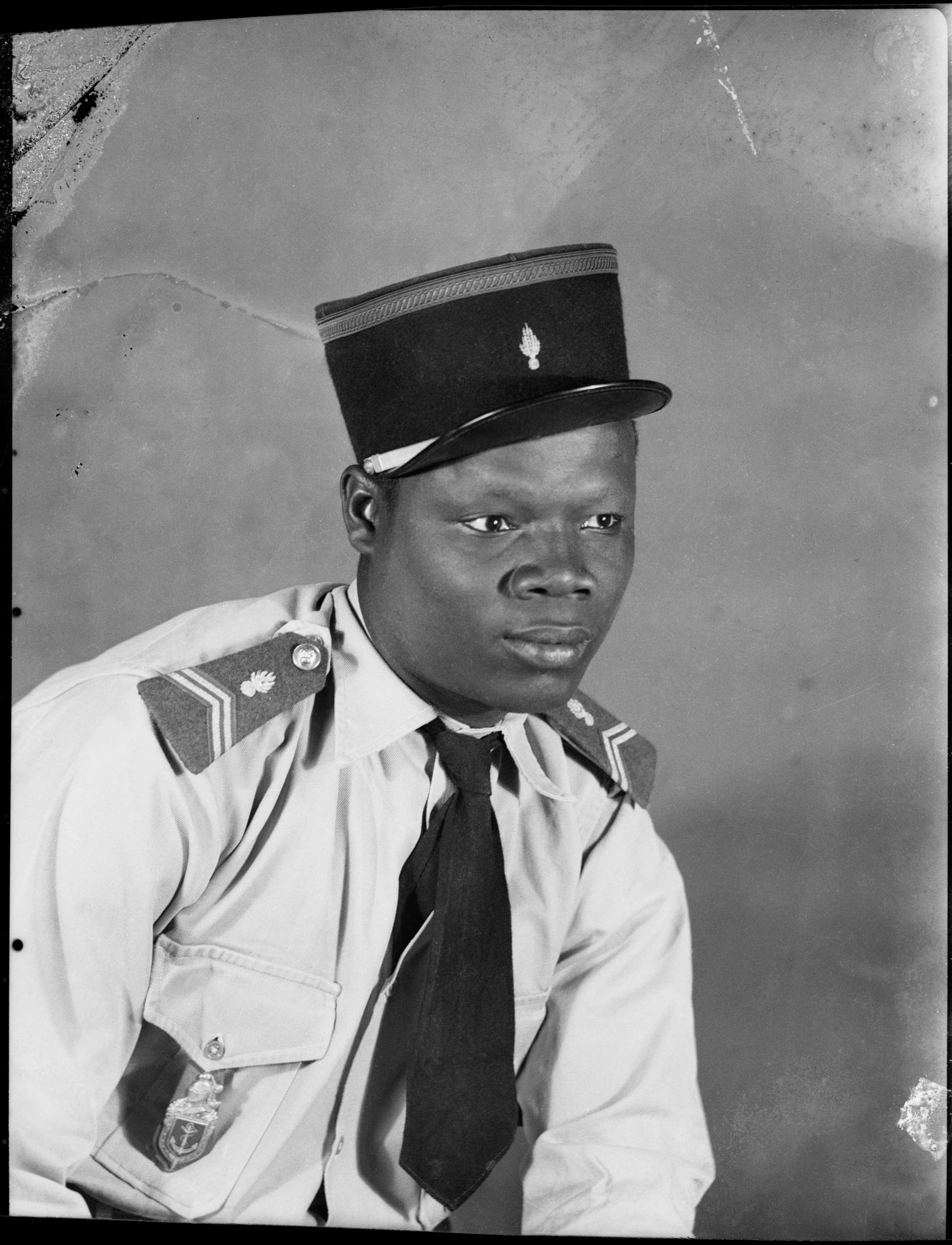

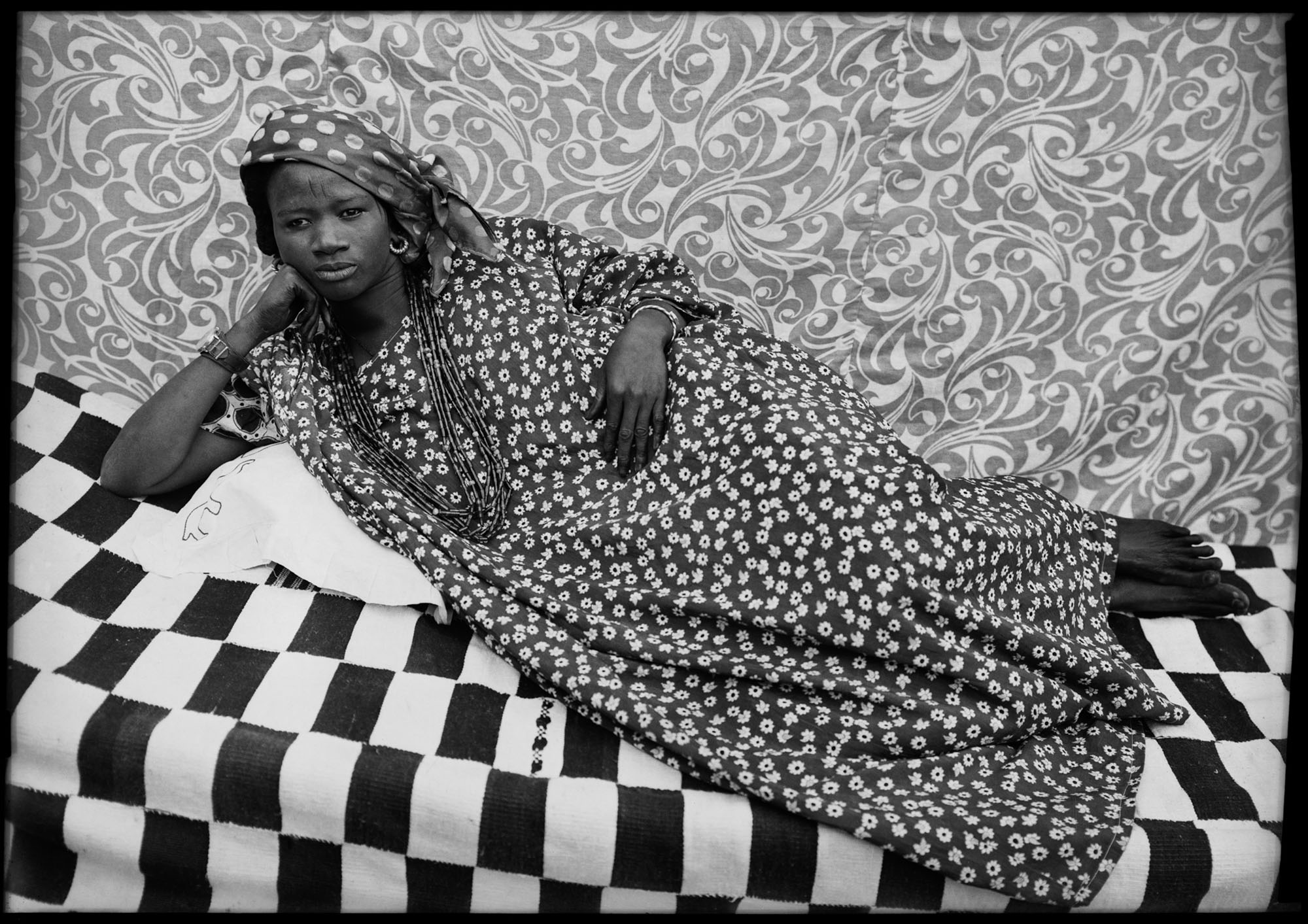

Celebrated as one of the most outstanding 20th-century photographers, Keïta ran a photography studio in the Malian capital, Bamako, between the late 1940s and early 1960s, where he shot black and white portraits of fashionably dressed people, with the patterned backdrops that he is perhaps best known for. He also documented the social and political landscape in pre- and post-independence Mali. That work was introduced to the West in the early 1990s, first anonymously in New York and then later identified, in group and solo exhibitions at galleries, museums, and foundations around the world.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1949-51

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1957-60

During the Mali trip, McKinley had extensive conversations with members of the artist’s extended family, who showed her his archive, which in turn became their contribution of previously unseen material, photos, and other items in their possession.

‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’, billed as the most extensive North American presentation of the artist, is now open at the Brooklyn Museum, and includes almost 275 works, including portraits, rare images, and never-before-seen negatives, textiles, jewellery, dresses, and the artist’s personal items. Keïta‘s family also put McKinley in touch with a surviving sitter of the artist, whose interview will be on view in the Brooklyn Museum exhibition.

'It’s a real range in terms of size, format, and exposure,' says McKinley, who organised the exhibition with Imani Williford, curatorial assistant of Photography, Fashion, and Material Culture at the Brooklyn Museum. 'I think what strikes me the most is that we’ve kind of really just begun to look at Keïta in particular, but also at the broader field of African photography in relation to world photography. So it’s very exciting for me. I think that it’s a new moment in terms of scholarship, and for viewers.'

Seydou Keïta, Malian, 1921-2001

Seydou Keïta, Malian, 1921-2001

The journey to the West African country was formative in many ways. 'I learned a lot about Keïta,' McKinley tells Wallpaper*. 'I would say [his family] disrupted a lot of my ideas about who he was and what the studio life was like. And I didn’t realise how involved the family was in the photographic process and how much they were a part of the studio life.'

The knowledge gained from the visit and conversations, McKinley adds, 'shaped everything. It changed the DNA of the exhibition, and even how I look at a lot of the works, because even many of the photos that are well known end up having family members as subjects.' McKinley cites an example of a sitter whom she initially thought was a famous singer, but who turned out to be a completely different person. 'It altered how I think about a lot of the work,' says the curator.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Stories about Keïta’s studio portraits often state that the sitters were middle-class Malians, but that wasn’t necessarily the case, as the list included migrant workers, civil servants, visitors from across West Africa, and some people who saved up for the occasion, 'because of the importance of having a photographic record or memento for the family', as McKinley puts it. 'I think it’s a really exciting moment to re-approach Keïta.'

‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’ is at the Brooklyn Museum until 8 March 2026

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1953-7