Philippe Parreno combines 20 years of footage to create ‘film of films, a seance of cinema’

The French artist premieres a new feature-length film at the 48th International Film Festival Rotterdam, reflecting two decades of filmmaking in the eye of the international art world

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When Philippe Parreno was a teenager, he and his friends would sneak their way through the back door of an adult movie theatre in one of the seedier parts of Échirolles, a rough suburb of Grenoble, southern France. The backstreet XXX dive was called Cinema Permanente, because porn played all day, all night.

At a public talk at the 2019 International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR), Parreno bashfully admits that watching the illicit movies acted as inspiration. In the dark, as the images writhed and morphed without sense of beginning, middle and end, so he formed his idea of what art should be. ‘We were always so alert, because we were scared of getting caught,’ he remembers. ‘But my sense of time became warped in the movie theatre. I started to think a permanent cinema is a beautiful idea.’

Parreno is here to present his new feature film, No More Reality Whatsoever, a combination of 20 years of disparate footage taken from dozens of art projects and edited together to create a ‘film of films, a seance of cinema’. The artist, who is 55, has the words ‘do so’ tattooed on his left wrist, a reference to the hypnotherapist Milton Erickson. He is soft-spoken, drinks tea over coffee, is dressed as if he might leave the cultured environs of the film festival for a quick hike along the canals of Rotterdam, and has a dry, self-deprecating sense of humour.

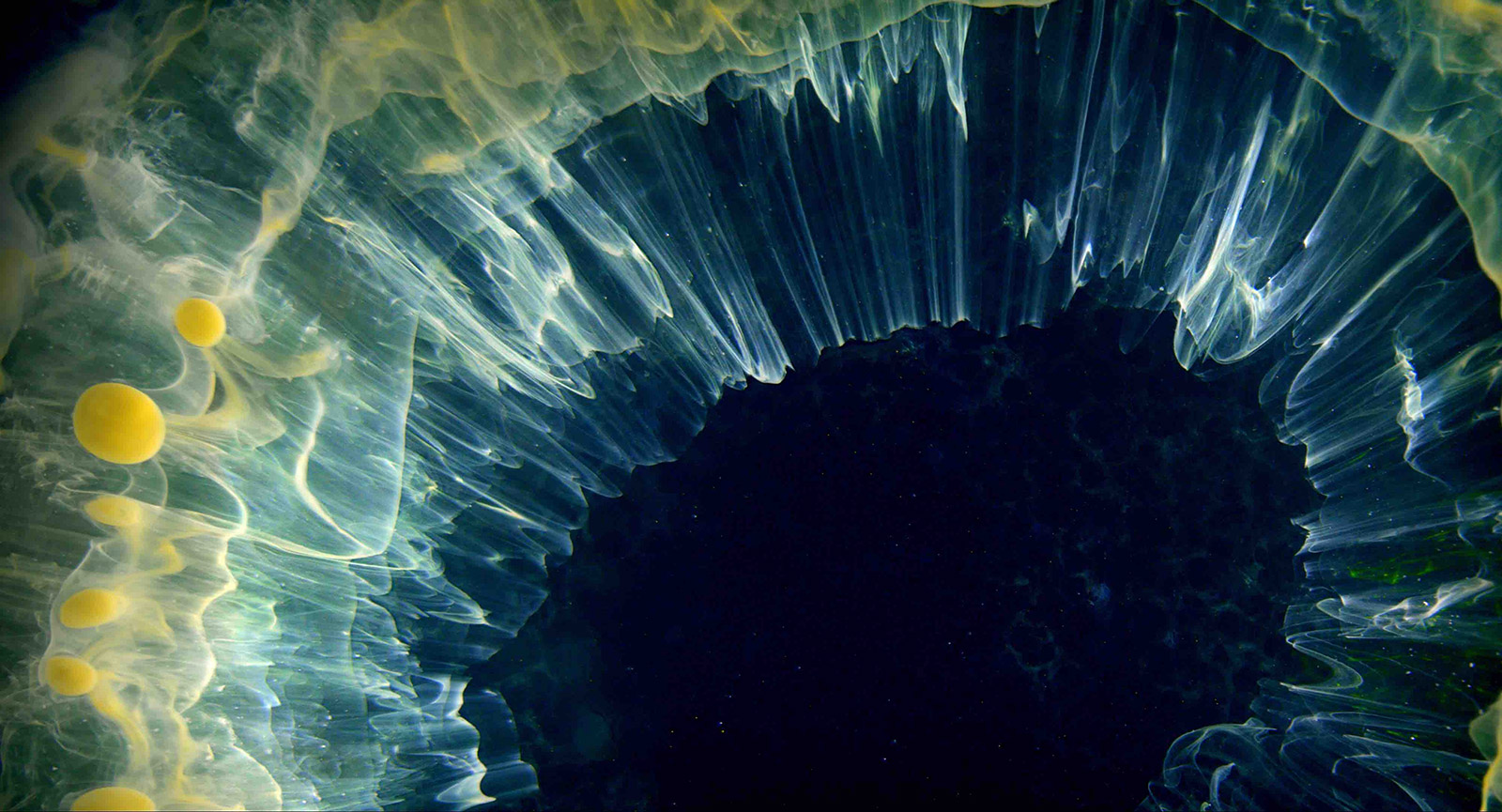

No More Reality Whereabouts, 2019, by Philippe Parreno film still, colour, 3D. © The artist.

As he is interviewed by Andrea Lissoni, curator of film and international art at Tate Modern, Parreno speaks of ‘practising white magic, but – don’t worry – never black magic’. ‘Magical forms have an ability to articulate a disparate idea,’ he explains. ‘We’re always looking for things to make sense, but maybe there’s another way to approach them. Besides, an artist is like a shaman. A film is like a seance.’ He is not someone, you get the impression, who takes himself too seriously. Indeed, he often talks about his work playfully, as if he is creating make-believe at a child’s birthday party.

But it’s possible to be both an irreverent and a serious artist. Few contemporary artists can point to a massive retrospective at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo (2013) or a large-scale solo exhibition in New York’s Park Avenue Armory (2015) or full usage of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall (2016). Parreno has done these and more, and now he is turning his hand to arthouse filmmaking, with a star turn in Rotterdam.

We’re always looking for things to make sense, but maybe there’s another way to approach them. Besides, an artist is like a shaman. A film is like a seance

Parreno talks of the ‘the exhibition as medium’. He is perhaps the best known member of a school of European artists who practice what in artspeak is referred to as ‘relational aesthetics’, a term coined in 1998 by the French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud (who was, at the time, Parreno’s roommate in New York). It’s the idea an artist should be the architect of a shared experience, the creator of a sensorial and transportive and essentially transient event, rather than the creator of a precious and permanent artefact. Rather than use a gallery as a hallowed space where static objects are hung in anticipation of reverence, it should be a space where we come to believe anything might happen, that disorientates our concepts of time and space, that upsets our inbuilt GPS.

‘It doesn’t matter what it is,’ he says of what he presents to the public in a gallery space. ‘It’s the way it appears that interests me. I’m interested in the nature of an image, and it’s relationship to what it’s supposed to represent. I’m interested by the production of a form in a public space, and how that form can change the public. All that stuff.’

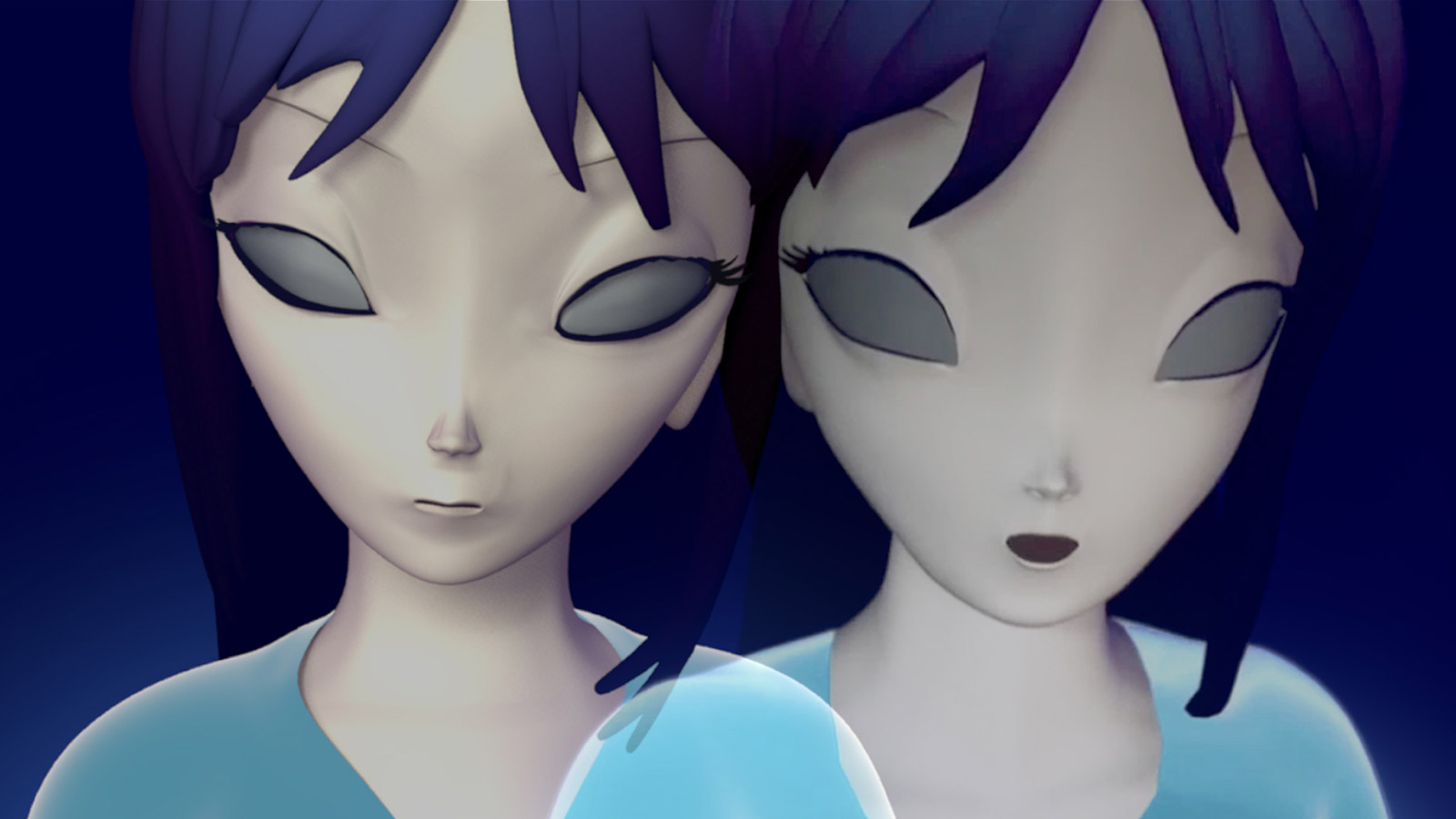

Anywhen, 2016, by Philippe Parreno, film still. © The artist.

No More Reality Whatsoever is playing directly before the latest film from the 88-year old Jean-Luc Godard, who is using IFFR to screen his new film Le livre d’image after it premiered in Cannes last year. The film is presented in the way Godard originally intended: in a specially designed replica of his home studio – Persian rugs included. The proximity pleases Parreno. ‘There was a strong movie culture where I grew up,’ he says.‘The legacy of the nouvelle vague [pioneered by Godard] and the literature around that had more of an impact in France than visual art I think.’

Parreno’s film starts with an introduction of sorts from a Rotterdam resident of Indonesian descent. The man is a Dhalang, a master of Indonesian shadow puppetry and ‘a fascination’ for the artist. The Dhalang waxes lyrical on the nature of time before singing a folkloric Indonesian hymn. He departs as Mikhail Rudy, a classical pianist, takes his seat at a grand piano, situated in front of the cinema screen, and starts playing a strange, atonal symphony, often layered on top of the film’s score.

Our 3D glasses are already in place. The split faces of a young women, a manga anime character called Annlee, is beamed onto the screen. Annlee addresses the audience directly, referencing how, in 2002, Parreno created the independent Annlee Association, transferring copyright ownership back to Annlee herself. The 3D is effective: close one eye, one huge manga Annlee is present on screen. Close the other, and a separate Annlee looms above us. The film moves from a female robot trapped alone in a hotel room to a train rolling through a rural town, the inhabitants of which stand and silently stare. We’re taking on a tour of the fishtanks in the restaurants of Chinatown New York, to a protest led by schoolchildren against the information age. ‘No More Reality’, their placards read.

No More Reality Whereabouts, 2019, by Philippe Parreno film still, colour, 3D. © The artist.

Parreno was born in Algeria. Échirolles is not all that far away from Marseille, where a certain athlete called Zinedine Zidane, also bald, also of Algerian descent, and also an artist of sorts, was born and raised. Parreno is still best known for his beautiful 2006 feature film of Zidane: a movie that simply follows the movement of the player over the course of a 90-minute football match between Real Madrid and Villareal.

Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait was co-created with the Turner-Prize winning artist Douglas Gordon, featuring a soundtrack from the Scottish post-rock band Mogwai and was shot in real-time using 17 synchronised cameras. During the creation of the film, Parreno got to know Zidane personally. I ask if he feels he shares anything with Zidane – a kinship of sorts? ‘Zidane told me that he always had to prove it, but only to himself. He was so focused on continually proving it to himself – that he was or could be a great athlete. He had to be intensely into the moment, as a great actor can also get intensely into the moment. He was able to ignore his presence totally. I think art can do that as well.’

Do you feel that need to prove yourself, I enquire. ‘Yes, totally,’ he says, with an emphatic nod. ‘I think I suffer the same as many people. The syndrome of the imposter? Imposter syndrome, yes... I have always had that. I try and combat it by trying to reinvent, by putting things in new contexts. It’s the best way I think, no?’

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the International Film Festival Rotterdam website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.