Holy orders: Not Vital’s installation in a remote Filipino province is worth a pilgrimage

At first blush, the decision by the Swiss artist Not Vital to build his latest installation – a concrete chapel set high on a windswept slope – in Bataan was entirely appropriate. Not far from this spot, in April 1942, the victorious Japanese army ordered around 76,000 Filipino and American POW soldiers to begin what eventually became known as the Bataan Death March towards Camp O’Donnell, around 100km away in Tarlac. Barely 54,000 soldiers survived the ordeal.

Vital is, however, careful not to characterise the chapel as a memorial to the atrocity. It is not consecrated, nor is it, despite the abstract references inside to The Last Supper – a giant porcelain piece by Vital – cast specifically to the Christian faith. That notion is discounted by an antique wooden statue of the rice goddess Bulol, carved by the Ifugao tribe in the northern Filipino provinces, that hangs on one of the rough-hewn interior concrete walls.

For Vital, the chapel is the latest in a line of surrealist buildings cum installations he has built out of local materials in remote locations around the world, such as Tschlin, Switzerland and Agadez, Niger. Getting here is, to put it bluntly, a schlepp. It’s a bone-crunching, jaw-smashing drive through a gully hemmed in by shadowy jungle and pockmarked with huge rocks, before you emerge into a sun-blasted plain on which the chapel sits, framed by low hillocks and lazily grazing cattle. In the monsoon months, the road is all but impassable by mechanical means; during construction, bags of concrete had to be brought in by water buffalos when rain turned the gully into a muddy river.

For Vital and his patron, Bellas Artes Projects – a non-profit arts foundation that Jam Acuzar set up in 2013 and runs from her father’s resort Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar in the nearby town of Bagac – the relative inaccessibility of the chapel is kind of the point. ‘It needed to be difficult to get to,’ says Vital, who, at 69, cuts a handsome, dignified figure that’s entirely in keeping with his stature as an eccentric statesman of the arts. The site becomes something like a myth, almost a pilgrimage.’

The door to the chapel is just large enough to fit one person.

And like all good myths, the chapel had its genesis as something slightly different. About a decade ago, Vital had begun painting seriously again after years of sculptural output. Haunted by a memory of Joan Miró creating the abstract mural at Barcelona’s airport, he produced a 12 x 5m oil canvas of The Last Supper – Christ and his apostles are represented by 13 black splotches against a white background. The work was eventually transferred to a ceramic panel produced in Jingdezhen, China, one of the world’s hallowed grounds for pottery production.

The dilemma of just where to install the work was solved when a friend introduced Vital to Diana Campbell Betancourt, whom Acuzar had recently appointed artistic director to her foundation. Bellas Artes Projects is located in a fantasist folly where over 40 historical houses from around the Philippines – rescued by Acuzar’s father from demolition, the oldest of which dates to 1640 – have been reassembled and repurposed into hotel rooms.

The foundation’s HQ, built in 1867, was once the home of La Escuela de Bellas Artes, the Philippines’ preeminent and oldest art school. As it turned out, Acuzar was already familiar with Vital’s work from her days in London when she studied at Sotheby’s Institute of Art and freelanced for an art dealer. ‘It’s so rare to find an artist whose works are so inaccessible and magical and yet leave such an indelible mark in the community,’ she says, explaining why she was quick to take on Vital’s project soon after they met.

Though the Las Casas grounds are vast, and there were plenty of potential sites, Vital eventually decided against installing his Last Supper there. Casting around for options, Acuzar brought the artist to her mother’s farm, an isolated en plein airfield in Saysain, about 20 minutes away from the resort. The moment Vital arrived on site, he knew this was what he was looking for. From there, the idea of housing The Last Supper within a simple minimalist structure developed fairly quickly, Vital seeing potential for his own take on the Rothko Chapel in Houston. Seasoned artisans from the Las Casas workshops were assigned to the project, toiling over the next year and a half to raise a trapezoid of poured concrete measuring 16 x 13 x 7.3m.

Vital’s ‘The Last Supper’, on ceramic panel, is installed on the far wall of the chapel, which is flooded in homage to the Philippine rice fields.

Vital’s original intention to have smooth interior surfaces was quickly abandoned when the coconut lumber casts were removed and revealed the imprinted patterns and textured surfaces of the fibres. He was so enamoured by the rough beauty that he also decided to leave the ceiling scarred by the concrete that leaked through the casts and dried like rocky stalactites. ‘It’s not completely perfect,’ he says happily.

The result is a structure that’s primitive in the best traditions of Brutalism and raw concrete architecture. Its silhouette is extraordinary in its geometric form, low hanging on one end and rising smoothly to a broad façade lined on the exterior by 13 highset steps. A horizontal aperture, a clerestory really, runs the entire length of the façade.

Visible from miles away, the building rises mysteriously out of the jungle; its silhouette suggests what a pre-Columbian temple might have looked like had Picasso been in charge of the works. ‘It’s such an arresting work,’ says Acuzar.

Inside, through a door just large enough to fit one person at a time, Vital has flooded the chapel in homage to the rice fields of the Philippines, allowing the water depth to start at 20cm at the entrance before tapering off as one walks up the slope towards The Last Supper, now finally installed on the far wall. During the day, light streams in through the clerestory and casts slanting straight-lined shadows on the walls and on the water. The irregular scorched circles on the wall make a particularly haunting motif, especially when juxtaposed against the figure of Bulol.

From left, Diana Campbell Betancourt, Jam Acuzar and Not Vital with the chapel in the background.

As a building, the chapel defies categorisation, something Vital is keen to avoid. ‘Is it art? Is it sculpture? Is it architecture? I don’t know.’ He shrugs. ‘I’m not an architect, I never went to architecture school. That’s why I’m so free to do this.’

For her part, Diana Campbell Betancourt is ecstatic. ‘Bataan is a place with a very charged history - and the chapel is a beautiful attempt to heal scars from a painful past and contemplate space for a more peaceful future,’ she says. Vital’s chapel is the first project on this particular site and Bellas Artes Projects will continue to produce similar works that involve the community, art, and nature on this and other sites owned by the Acuzar family in Bataan. The dream is that these works will eventually coalesce into a public sculpture park.

And perhaps, one day soon, Bataan will shed the horrors of the 1942 death march with which it is currently synonymous and become, instead, a byword for endeavours considerably more uplifting. Vital is hopeful: ‘You just have to believe.’

As originally featured in the June 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*219)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Bella Arts Projects website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Daven Wu is the Singapore Editor at Wallpaper*. A former corporate lawyer, he has been covering Singapore and the neighbouring South-East Asian region since 1999, writing extensively about architecture, design, and travel for both the magazine and website. He is also the City Editor for the Phaidon Wallpaper* City Guide to Singapore.

-

‘The point was giving ordinary people access to bold taste’: how Ikea brought pattern into the home

‘The point was giving ordinary people access to bold taste’: how Ikea brought pattern into the home‘Ikea: Magical Patterns’ at Dovecote Gallery in Edinburgh tells the story of a brand that gave us not only furniture, but a new way of seeing our homes – as canvases for self-expression

-

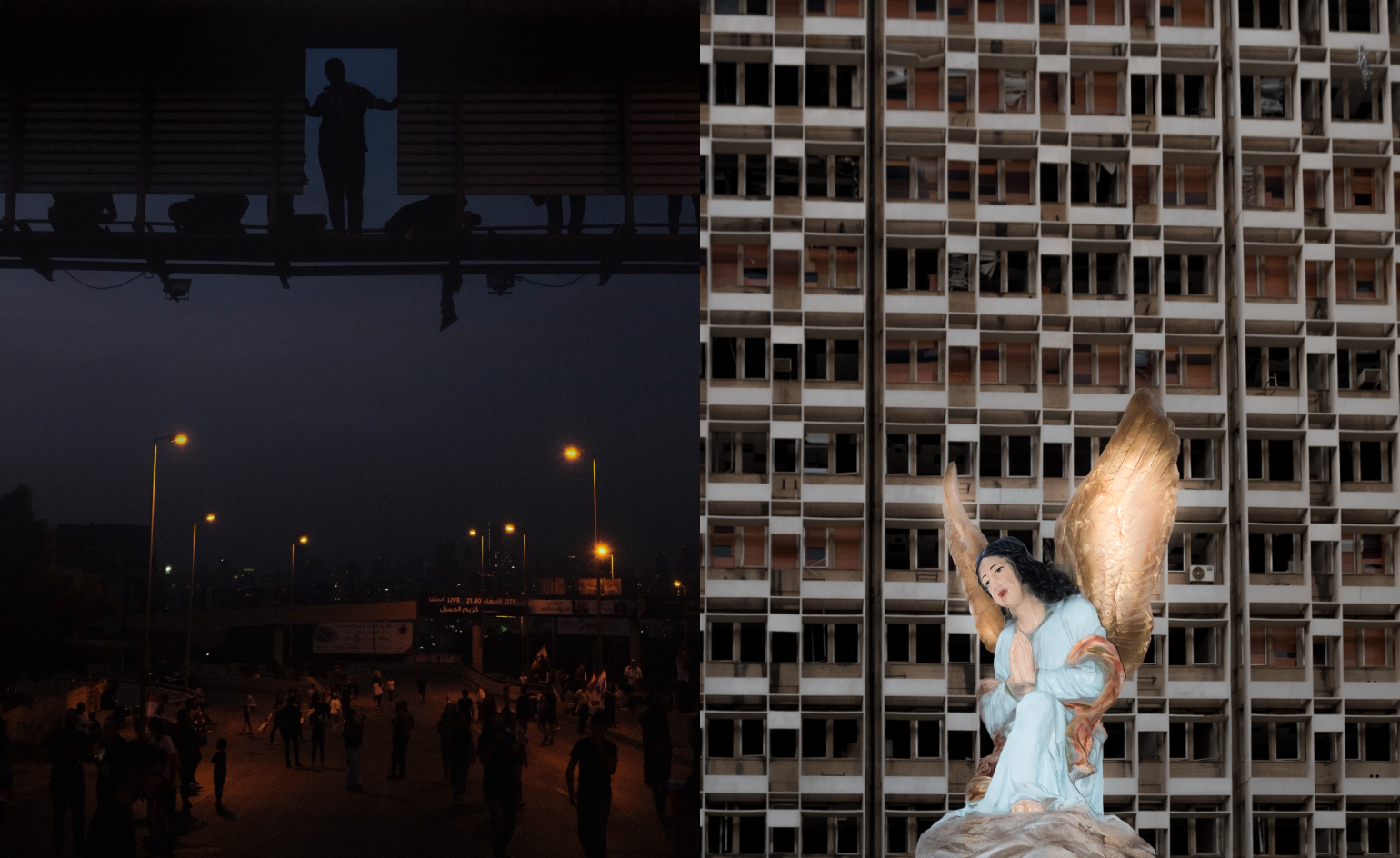

A poignant Lebanese photo book reflects on the memory of home

A poignant Lebanese photo book reflects on the memory of homeCharbel Alkhoury conveys the ache of seeking asylum in a photography book that documents not just a place, but its lingering afterimage

-

George Lucas’ otherworldly Los Angeles museum is almost finished. Here’s a sneak peek

George Lucas’ otherworldly Los Angeles museum is almost finished. Here’s a sneak peekArchitect Ma Yansong walks us through the design of the $1 billion Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, set to open early next year

-

Photographer Mohamed Bourouissa reflects on society, community and the marginalised at MAST

Photographer Mohamed Bourouissa reflects on society, community and the marginalised at MASTMohamed Bourouissa unites his work from the last two decades at Bologna’s Fondazione MAST

-

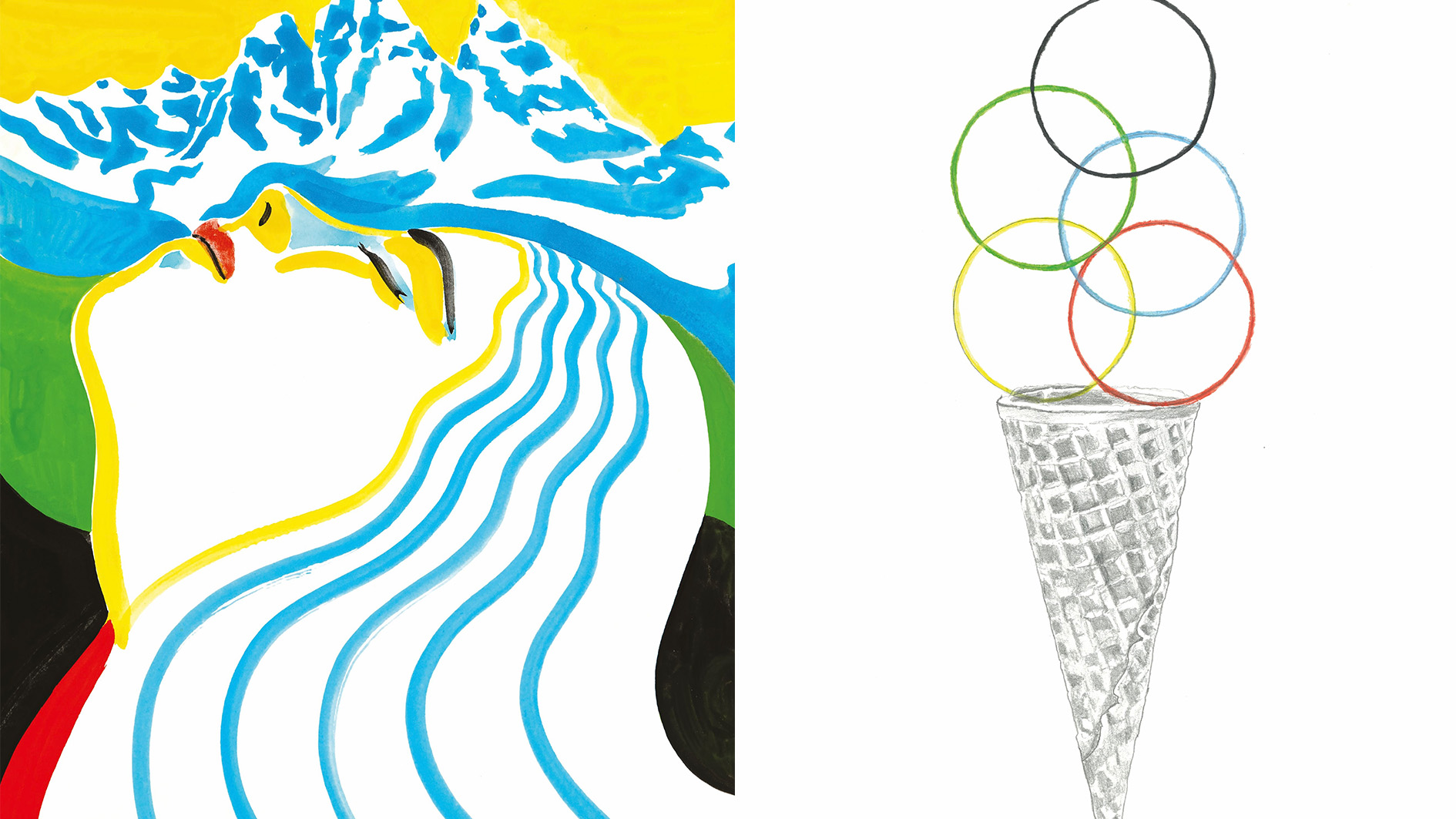

Ten super-cool posters for the Winter Olympics and Paralympics have just been unveiled

Ten super-cool posters for the Winter Olympics and Paralympics have just been unveiledThe Olympic committees asked ten young artists for their creative take on the 2026 Milano Cortina Games

-

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaigns

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaignsBest known for the controversial adverts he shot for the Italian fashion brand, former art director Oliviero Toscani has died, aged 82

-

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TV

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TVStefano De Luigi's monograph Televisiva examines how Berlusconi’s empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership

-

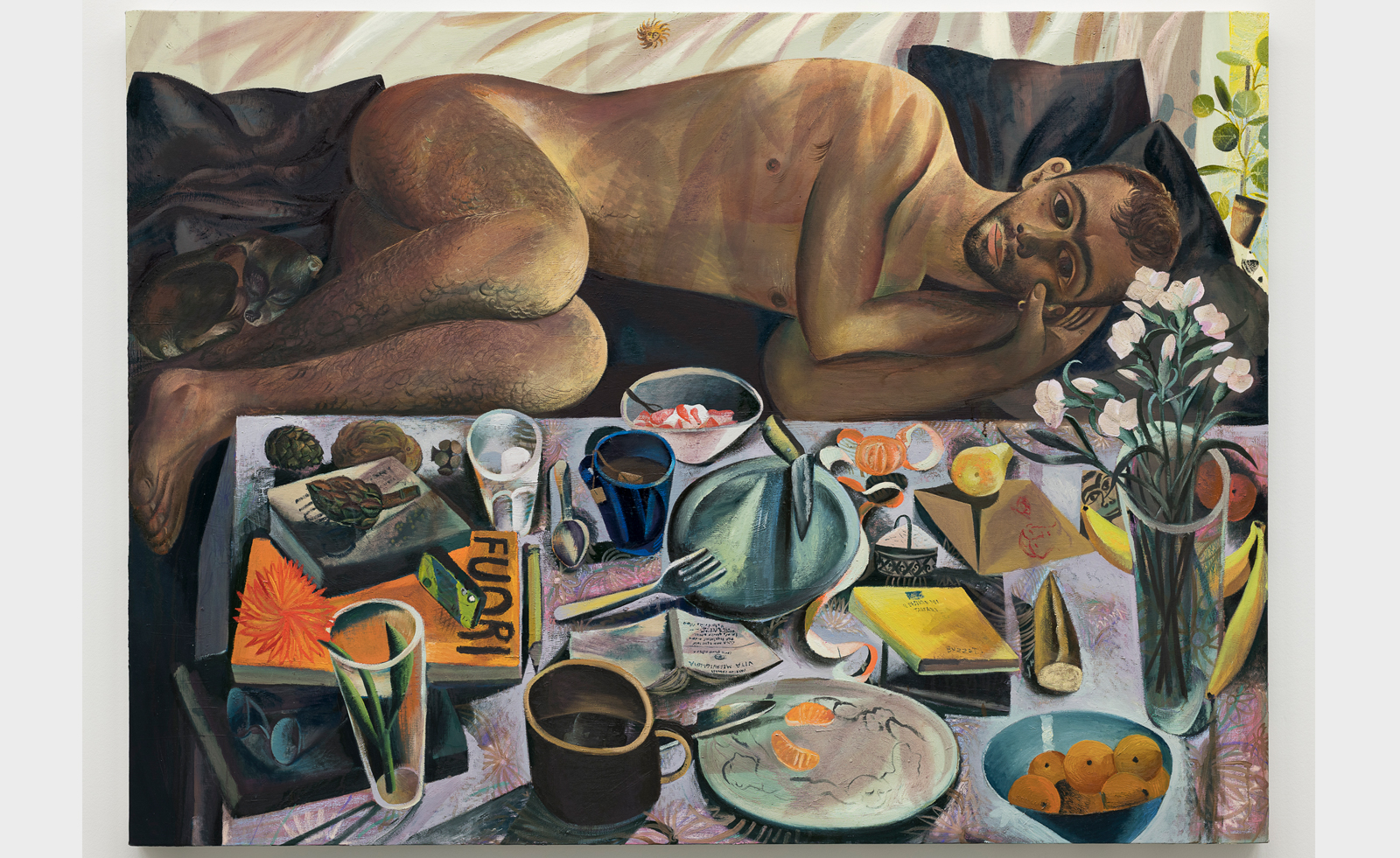

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in Italy

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in ItalyLouis Fratino’s 'Satura', on view at the Centro Pecci in Italy, engages with queer history, Italian landscapes and the body itself

-

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art market

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art marketArtist Andrea Fraser’s retrospective ‘I just don't like eggs!’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, Italy, explores what really makes the art market tick

-

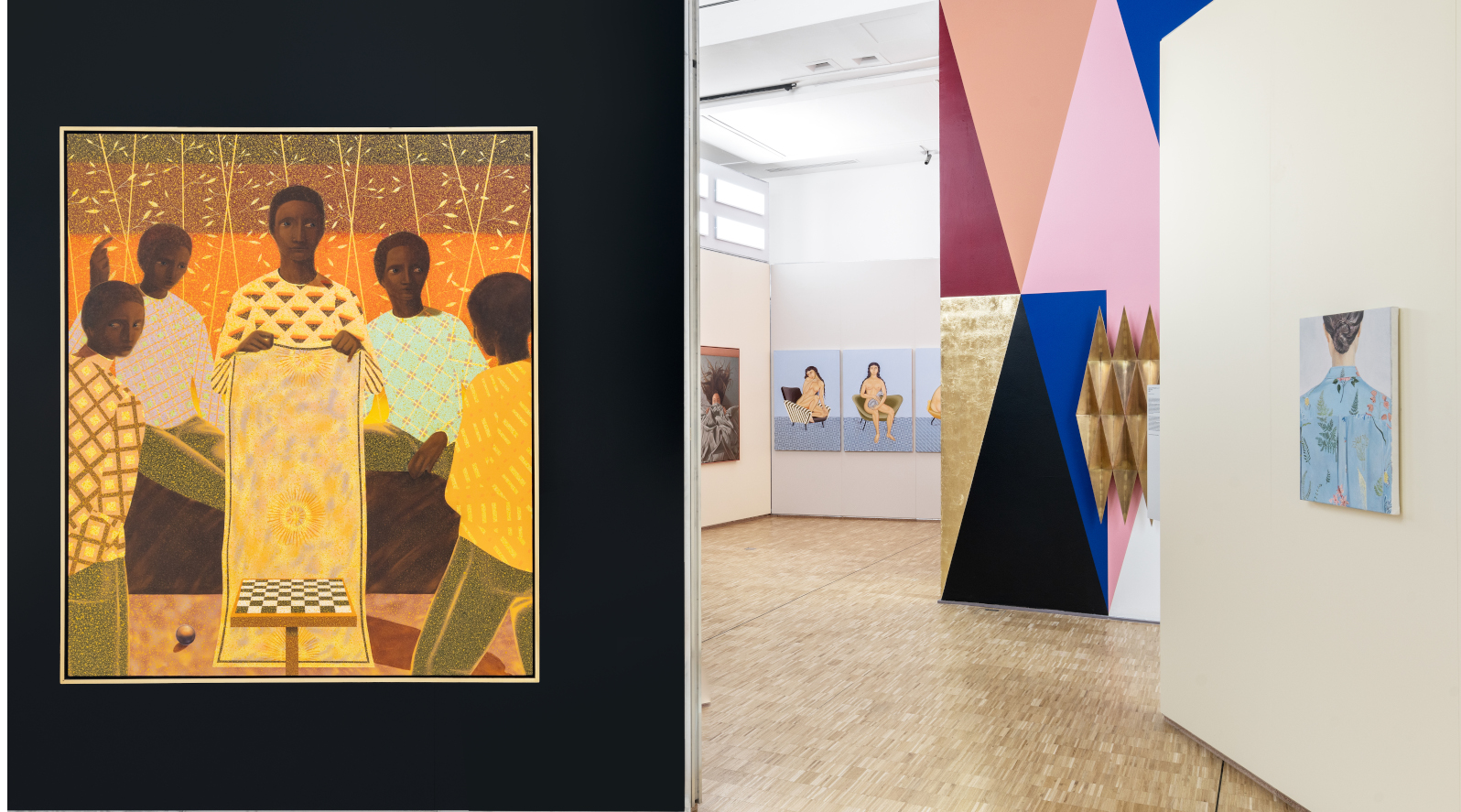

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian art

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian artThe latest Triennale Milano exhibition, ‘Italian Painting Today’, is a showcase of artworks from the last three years

-

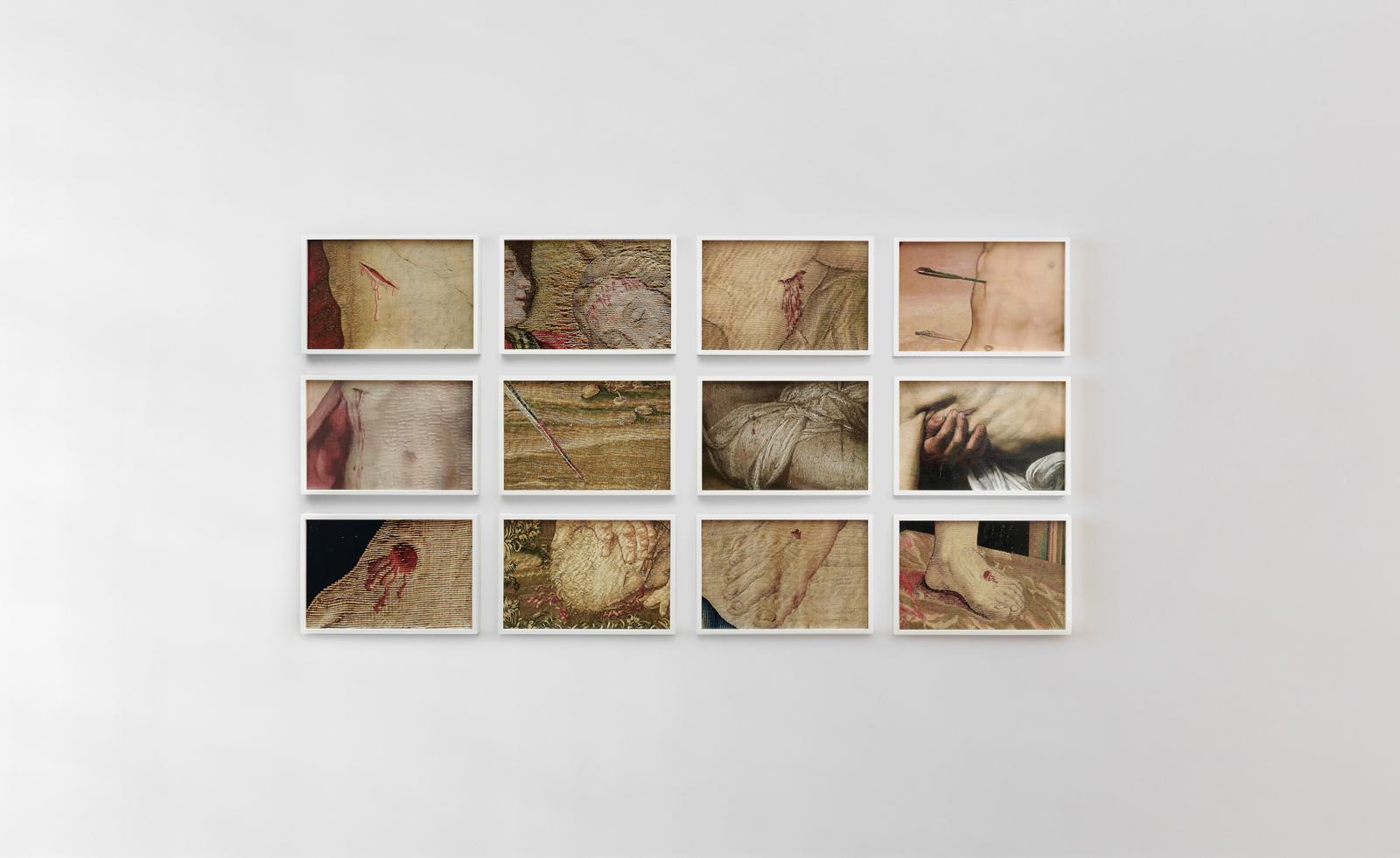

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in Naples

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in NaplesCatherine Opie's new exhibition ‘Walls, Windows and Blood’ is now on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples