No retreat: Parviz Tanavoli still dominates Iran’s cultural scene

I arrive at the threshold of Parviz Tanavoli’s like a thirsty pilgrim. Ninety minutes of bus travel through heated Vancouver gridlock leads me to his home in remote Horseshoe Bay. I think of Iran’s saqqakhanehs, the small drinking fountains found recessed in walls around the country, that inspired both Tanavoli’s work and the Saqqakhaneh art movement he spearheaded in the 1960s when he first tried to marry traditional Persian idioms with contemporary art. I shake off the summer heat and prepare to drink deep at the well of a master.

For the so-called ‘father of modern Iranian sculpture’, being far from the madding crowds is a good thing. His home, with its vast Pacific vistas, offers pure refuge. ‘Nothing happens here,’ he sighs contentedly as a pleasure boat cruises past his home – an early Arthur Erickson bungalow expanded by Iranian architect Foad Rafii in the 1990s to contain some of Tanavoli’s most beloved works and his studio.

In contrast to safe, antiseptic Vancouver, Tanavoli’s Tehran – where he spends half his time – is a frenzied whirlwind. As an upstart bad boy of Iranian art in the early 1960s, his first show almost caused a riot. In the cloistered world of Tehrani intelligentsia, his clever subversion of straightjacketed tradition – namely the use of a toilet ewer inserted into a handmade Persian rug – was perceived as an insult to the art world. In 1965, the Borghese Gallery, a cutting-edge art space run by a Frenchwoman who exhibited his work, had to close its doors after a mob threatened to burn it down.

‘I was fed up with pretty art, pretty women, pretty objects, pretty paintings,’ explains Tanavoli as he offers tea and sweets while his elderly Persian cat keeps watch. ‘I wanted to show that what we are ashamed of in our daily life could be art.’ To that end faucets, locks, pieces of textile, old shoes and mattresses and a variety of found junkyard treasures became his palette.

While he celebrated everyday objects he also embraced devotional devices, such as the locks fastened by worshippers to the lattice grillwork of Shia shrines and saqqakhanehs. At once irreverent and deeply respectful of folk tradition, Tanavoli’s work has always danced deftly between the sacred and the quotidian – finding something of each in the other.

His signature Heech (farsi for ‘nothing’) series, which began as a protest against the emptiness of the Iranian art world in 1965 and morphed into a political protest about Guantanamo in 2005, evokes both a Sartrean and Sufi ‘being and nothingness’ aesthetic. ‘Nothingness is a very important idea in Persian tradition,’ says Tanavoli. ‘Just read Hafez or Rumi.’ (The latter famously penned that we came whirling out of nothingness scattering stars like dust).

Indeed there is something of the Sufi in Tanavoli, a down-to-earth mysticism with a healthy sense of humour. And there is still a childlike sense of wonder in his work that recalls the boy who was fascinated by the travelling locksmiths of Tehran. ‘They would cry out qoflsaz (locksmith),' explains Tanavoli, ‘and would carry a metal disc on their shoulders with hundreds of keys, as well as a grinder, a tripod and a few files. From that they could fashion keys for any lock. It was like magic.’ As a boy Tanavoli became an avid amateur locksmith, fashioning keys for friends and families. As the son of a restaurateur who catered to religious Shia pilgrims, he was also entranced by their devotional rituals and objects. ‘Shrines in Iran are beautiful,’ he says, recalling childhood journeys to Mashhad and Qom and to his favourite shrine, dedicated to Queen Esther. ‘They are like museums made by masters, with textiles, ceramics, metal work. Pilgrims grab hold of the grills and make wishes and prayers and ask the imams to cure them,’ he continues. ‘That really struck me. When a human hand grabs metalwork – that’s super-real.’

While the middle-class Tanavoli was never fully embraced by the Tehrani elite, he enjoyed the patronage of Farah Diba, Empress of Iran and wife of the late Shah, who became an unlikely midwife to the birth of contemporary Iranian art. She discovered the young Tanavoli at the inaugural Tehran Biennale, which she sponsored, and appreciated his work.

This support almost cost him his life: in the violent aftermath of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, he had to remain in hiding for several months, until the coast was clear. ‘There were many mobs circulating at the time,’ he said, ‘taking advantage of the chaotic situation. There were rumours they would ransack my house.’

His home in the district of Niavaran, near the Shah’s old palace in the north of Tehran, was designed in 1967 by the architect Kamran Diba – a cousin of the Queen – who later designed the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, inaugurated in 1977. It was Diba’s only residential commission and became Tanavoli’s base of operations and studio site.

A few months after the Revolution, he emerged from hiding to find that his work had been banned and his passport cancelled. He was a prisoner in his own land. But he used his ten years of internal exile productively, travelling to the north and mixing with the nomadic tribes whose colourful rugs and textiles were celebrated in Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s film Gabbeh. Tanavoli became a student of traditional folkloric art and artisanal creations, writing several books on the subject. A collector by nature, he has filled his two homes with carpets as well as pottery and ceramics – some of which date back to pre-Islamic times.

When his passport was returned to him in 1989, Tanavoli emigrated with his young family to Canada, settling in Vancouver, where a growing community of Iranians – among them well-known artists and architects such as Houshang Seyhoun (who designed the Omar Khayyam mausoleum) and Hossein Amanat (whose monument to the Shah, renamed the Freedom Tower, remains a civic beacon in Tehran) had also settled. ‘Vancouver reminds us of the Caspian Sea area,’ explains Tanavoli. It has also traditionally been a more welcoming destination for Iranians than the US.

While he appreciated the ‘peace and sense of freedom’ he found in his adopted home, he missed ‘the spirit and the energy of Iran’. Before long he became as migratory as the nomads who so captivated his imagination. He now spends about half his time in each place, coming and going at three-month intervals.

It was that undeniable Persian soul (and optimism borne of the Iranian president Mohammad Khatami’s new liberal perspective) that inspired him to take up an intriguing offer in 2002 by the then-mayor of Tehran, Mohammad-Hassan Malekmadani, who suggested he turn his house into a museum. But being a cultural guinea pig proved dangerous. ‘The city of Tehran bought my house and 60 artworks, all at less than half-price,’ explains Tanavoli. ‘But my condition was that they never be moved or sold.’ Only a few months later, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became mayor of Tehran. ‘He didn’t like the idea of a museum,’ says Tanavoli with typical understatement. Ahmadinejad called it ‘Western rubbish’ and suggested the house be turned into a mosque. It took Tanavoli six years of court battles to win back his house, which he was awarded in 2008 – the same year as his sculpture The Wall (Oh Persepolis) sold for £1.87m at an auction in Dubai, setting a new record for Middle Eastern artists and making him the highest-earning Iranian artist. But he is still fighting for his artwork. Last year a group of municipal workers broke into his home in Tehran and took the remaining artwork by force, damaging some of it in the process. His filmmaker daughter Tandis was there and recorded it all on video.

Beyond the anti-Western rhetoric, Tanavoli believes the motivation for absconding with the art is monetary. Just as ISIS in neighbouring Iraq sells antiquities on the black market even as it blows up monuments, so does the Iranian regime play a devious game. But Tanavoli’s spirit soars above such pettiness. ‘We are stronger than these extremists,’ he says. ‘The Iranian soul will prevail.’ And while the legendary artist is ignored in sleepy Vancouver and harassed by Iranian authorities, he is currently being celebrated by the Great Satan: his first retrospective, held this year at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, met with critical acclaim. Twelve of his works are also being shown at the Tate Modern in London this autumn as part of the ‘The World Goes Pop’ exhibition.

Like his emblematic work Heech Lovers – two curved, calligraphic letters locked in an irrevocable embrace – Tanavoli has remained loyal to his difficult, beloved Iran – keeping the faith through revolutions and uprisings, queens and quagmires. And through it all, the master locksmith of the Persian heart has set free the Iranian spirit, channelling it through a contemporary idiom, and giving it new life.

As originally featured in the November 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*200)

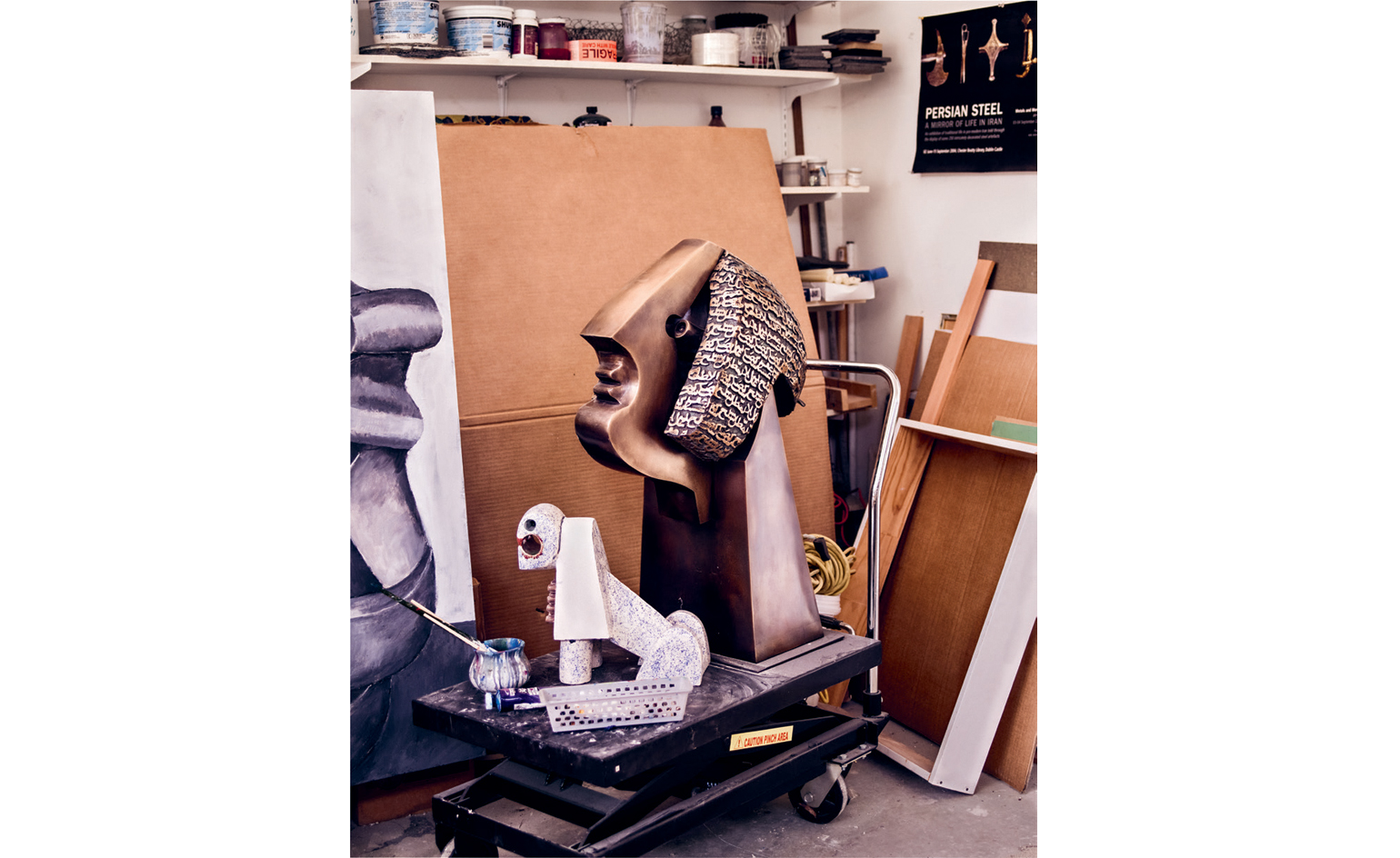

Tanavoli's studio with some of his works. The large bronze on the left is Twisted Heech, 2012. Heech is his signature series, evolving since 1965, when it began as a protest against the emptiness of the Iranian art world

From left, Lion, 2014, glazed eartherware, and Poet's Head, 2009, bronze

Tanavoli works on a plaster Heech

Also at Tanavoli's Vancouver base, Heech Lovers, 2013, stainless steel

INFORMATION

‘The World Goes Pop’, featuring 12 of Tanavoli’s artworks, is at Tate Modern until 24 January 2016

Photography: Mark Mahaney

ADDRESS

Tate Modern

Bankside

London, SE1 9TG

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.