Mike Nelson fashions a sculptural collage of Britain’s industrial age

Part salvage yard, part sculpture court, the installation artist’s commission for Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries brings alive the zenith of British industry

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In 1917, at an exhibition at New York’s Society of Independent Artists, Marcel Duchamp showed for the first time his sculpture Fountain. The curators of the show were so appalled by the French artist’s placing of a common urinal in their sainted gallery space that, the night before the opening, they orchestrated its removal – and slung it in with the rubbish. Duchamp wasn’t perplexed. Nor did he raise a stink. He simply walked a few blocks through Manhattan, found the hardware store in which he’d first discovered the urinal, bought another for a few dollars and carried it back to the gallery. He again signed the name R Mutt, a reference to a cartoon strip that thumbed its nose towards the aristocracy.

The French-American dadaist called it ‘readymade’ art. He was frustrated with the artist’s right to self-determination. The New York establishment – the galleries, the institutions, the dealers and the critics – had the power to decide what constituted art. And they had a narrow view of it. By plucking a urinal from a hardware store (one that happened to maybe possibly slightly resemble a woman’s labia), and put it in a high-end gallery space, Duchamp upended the hierarchy of the art world. It was a fearsome, revolutionary joke.

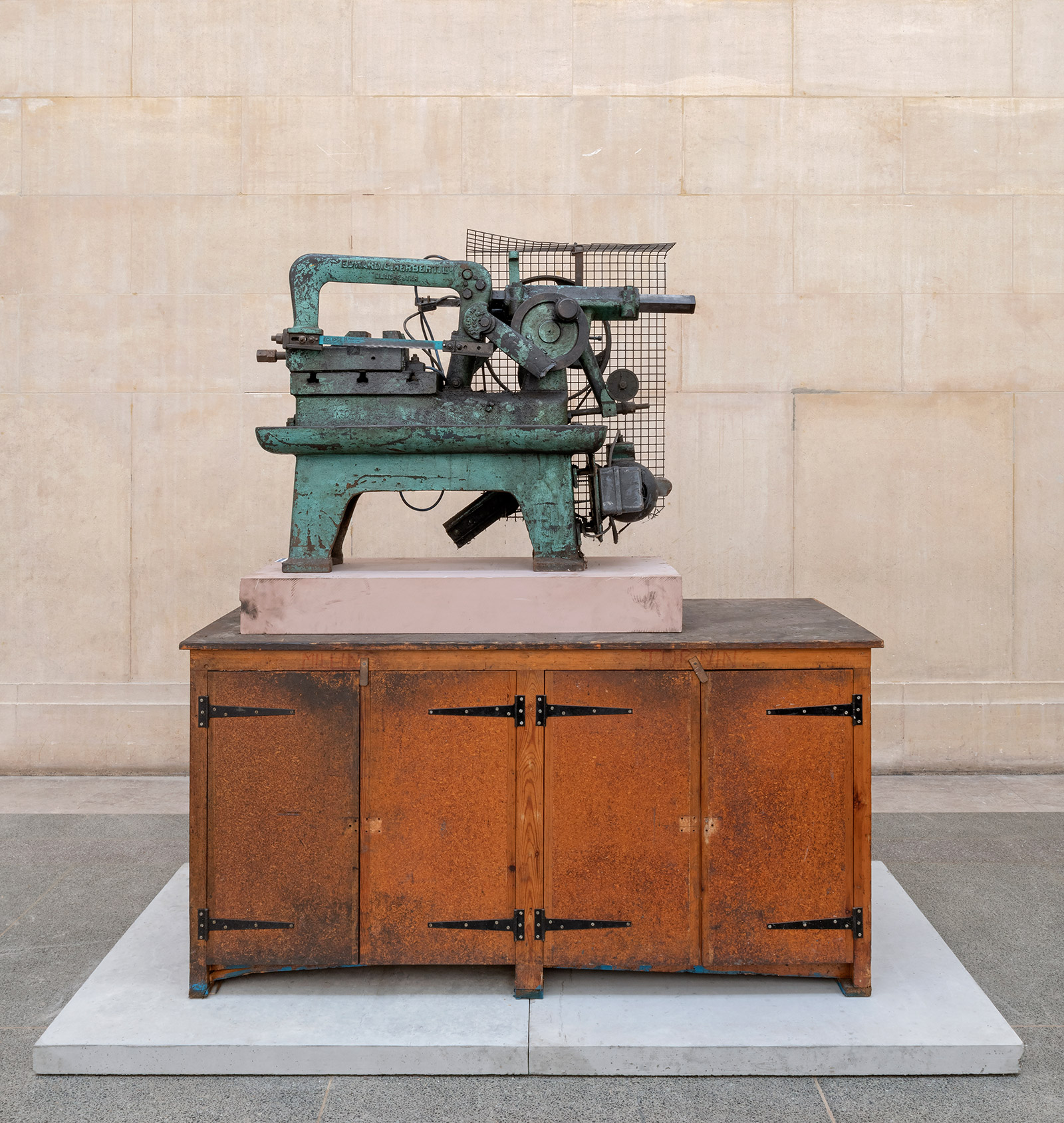

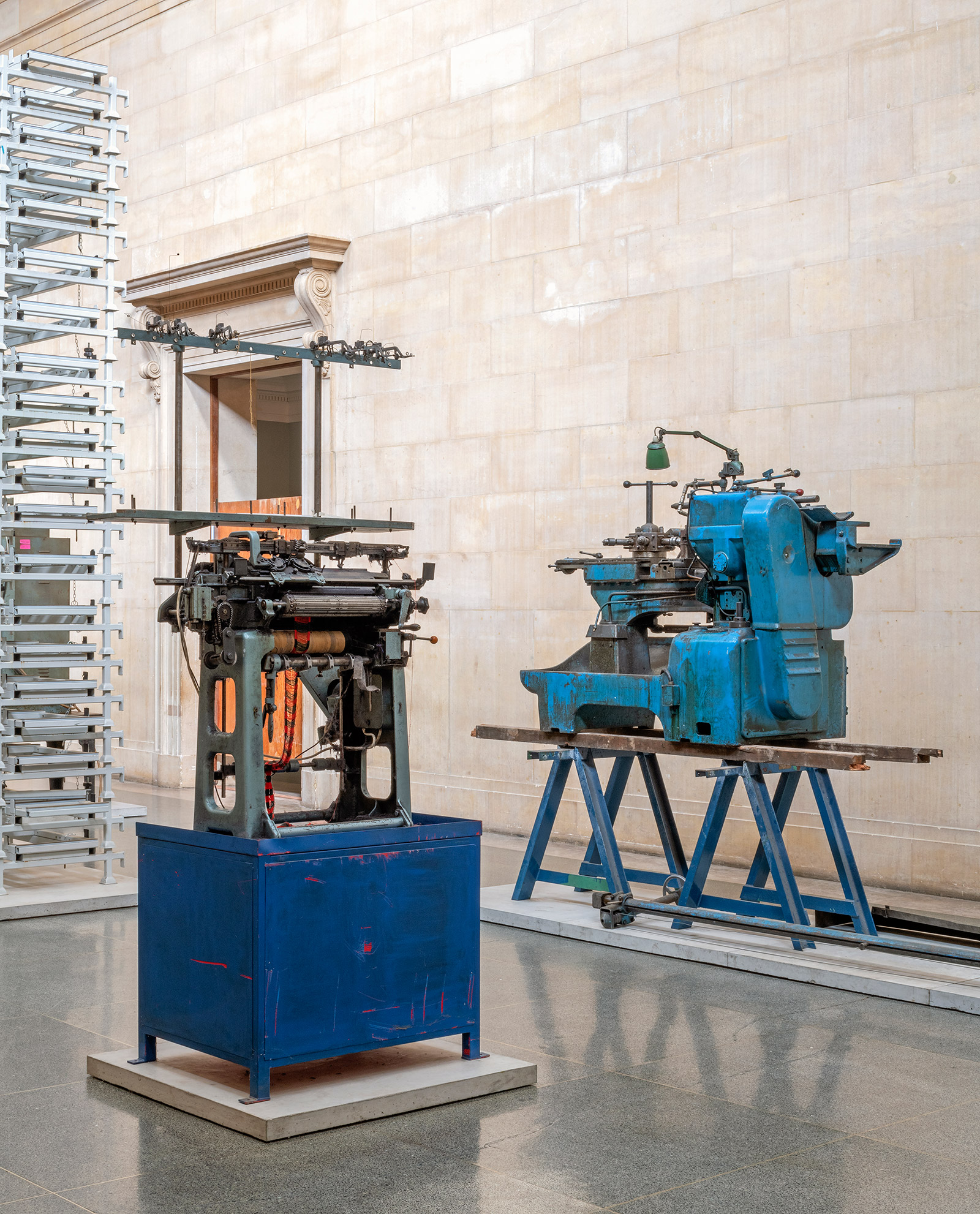

Since the age of Duchamp, readymade art has become an established idea in the art world, particularly in sculpture. But has anyone ever interrogated the term like British installation artist Mike Nelson? For Tate Britain’s annual commission, Nelson has spent the last decade scouring online auctions of company liquidators and salvage yards. Bit by bit, he has amassed a collection of objects which brings alive the bygone days of British industry in a work titled The Asset Strippers. Often these relics were sold for nothing more than scrap. Nelson saw his purchases as a process of collecting ‘artefacts cannibalised from the last days of the industrial era’.

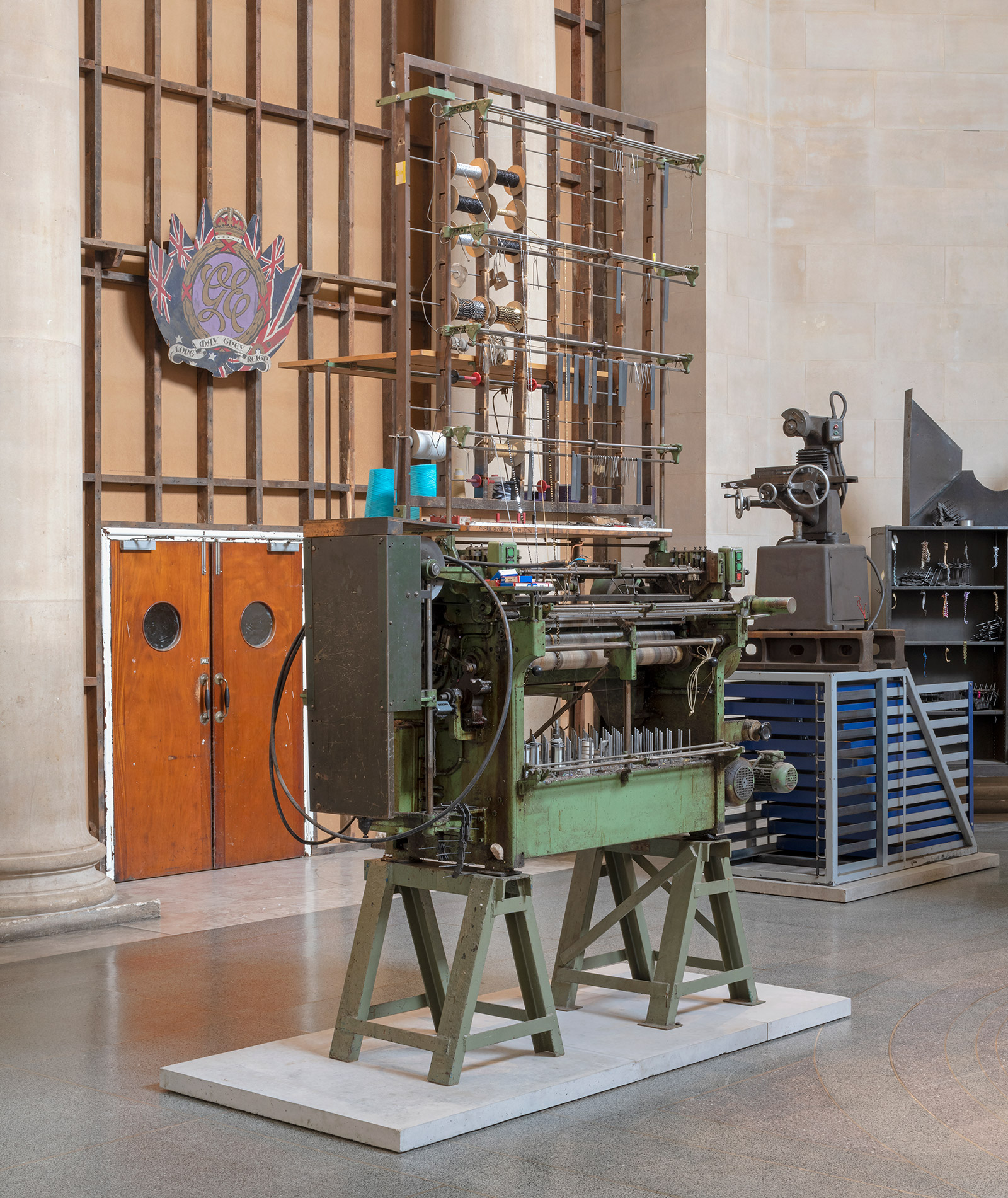

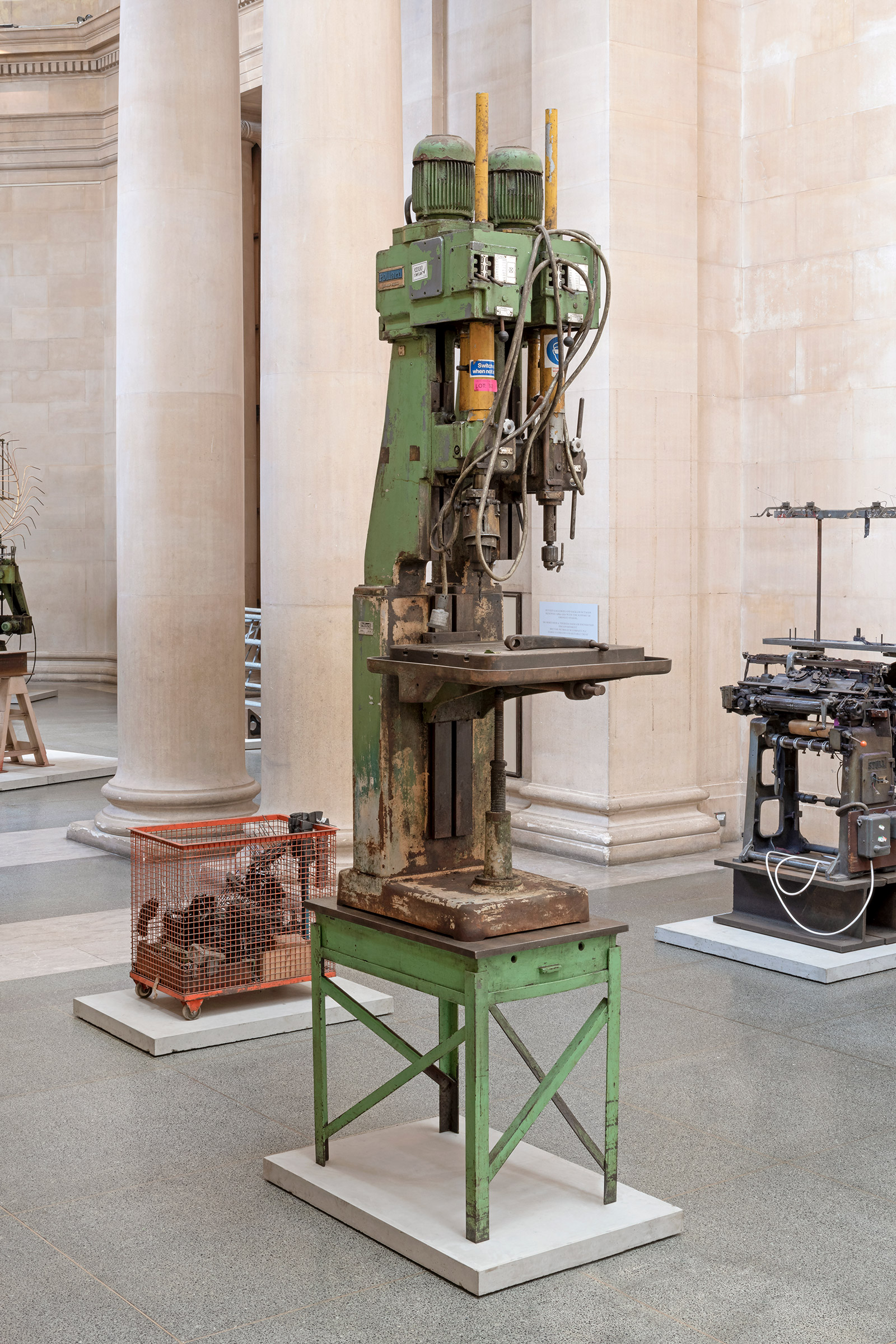

Nelson has now grouped these objects together at the centre of the London institution’s Duveen Galleries, displaying knitting machines from textile factories, woodwork stripped from a former army barracks, graffitied steel awnings used to secure a condemned housing estate, and doors from a defunct NHS hospital. Some still objects bear their lot numbers from the auctions. They still have traces of the materials they created – a line of cotton here, a sequin there, a drop of paint here. They still emit the pungent, oily smell that is distinct to a working factory. ‘All the work was made over a one month period,’ the show’s curator Clarrie Wallis tells us. ‘The objects were bought in and worked on in situ. The pure amount of sculpture he created in that time is incredible. Mike wanted to radically transform the space.’

RELATED STORY

Nelson grew up in Loughborough in the English midlands in postwar Britain. His parents worked in a textiles factory. This wasn’t unusual – the British economy at the time was based on the premise of making stuff. What we see before us, therefore, are the loved mechanisms that someone spent their careers with. Look carefully and you can see where the hard metal of the machines has been worn down by use, smoothed by repetition.

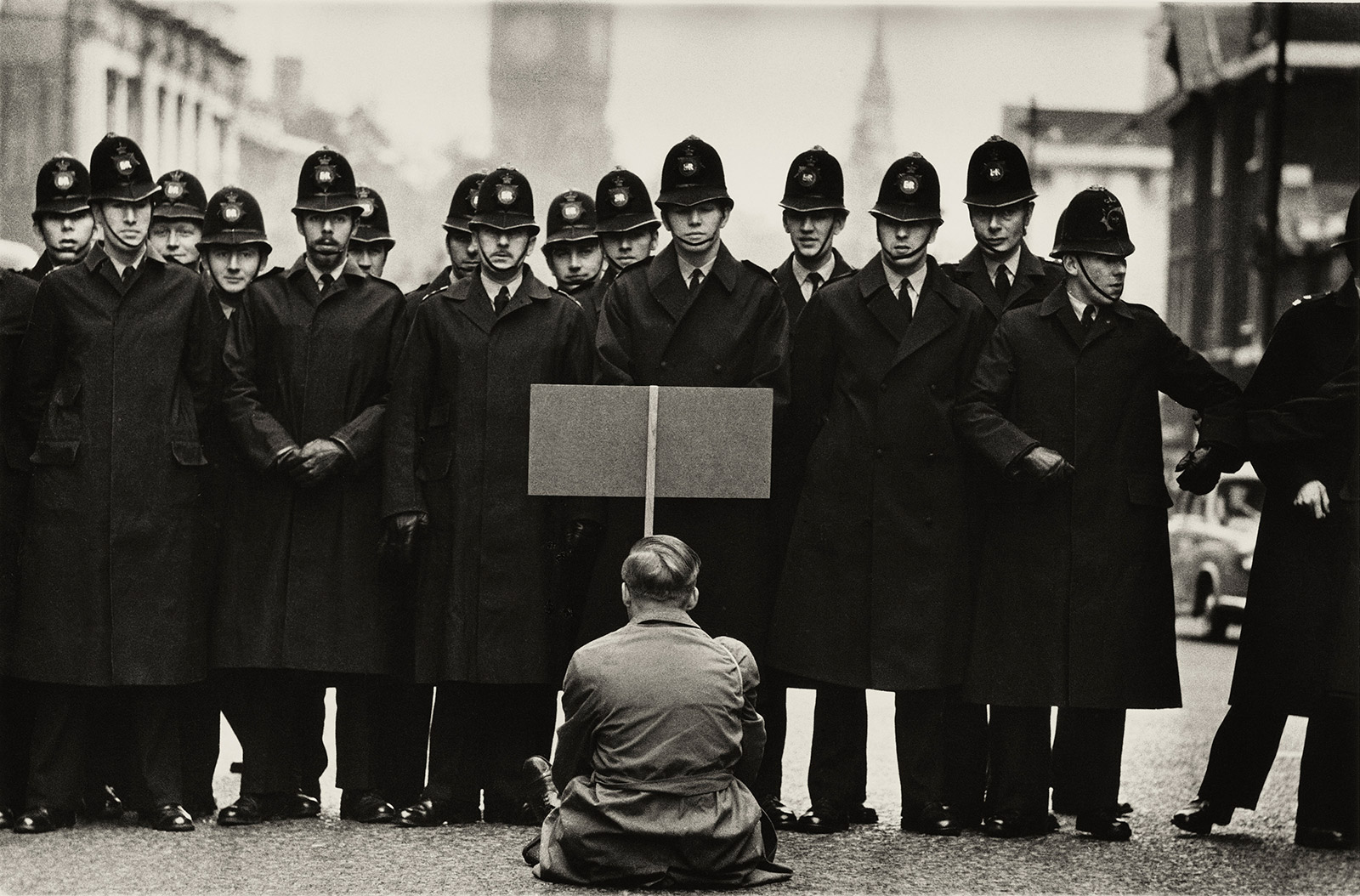

‘The factory that Mike’s parents worked in closed down during the Thatcher era,’ Wallis says. ‘So these objects are very close to his heart. He wanted to create something akin to an archaeological site, but with material from the recent past. It is monumental sculpture undercut with socialist principles.’ By placing these once junked relics in the neoclassical halls of the Tate’s Duveen Galleries, Nelson therefore finds a sculptural way to tell the stories of the people who once busied themselves on these objects. ‘It’s like walking into a cross between a sculpture court and a salvage yard,’ Wallis says. ‘But the objects are primarily anthropomorphic. You think about the people that used them.’

It is monumental sculpture undercut with socialist principles.

Nelson has been shortlisted for the Turner prize on two occasions, and represented Britain at the 2011 Venice Biennale. Past exhibitions have seen him create a dramatic space in which we can image a story unfolding: he evokes a person, or a group, by showing us their den. Here, he recalls his own childhood, one indelibly connected to a Britain that has largely gone. It’s a psycho-geographical and psycho-historical usage of found ephemera.

The artist says in his notes for the exhibition: ‘Their manipulation and arrangement subtly shifts [these objects] from what they once were into sculpture, and then back again to what they are.’ What would Duchamp make of Nelson’s readymade art? For this is sculpture which was once made and then used over decades – hauled, scrapped, saved and then exhibited. Nelson might have advanced Duchamp’s old term. In doing so, he might just have provided us with a masterpiece.

INFORMATION

‘The Asset Strippers’ is on view until 6 October. For more information, visit the Tate website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.