Iceland’s Sequences Festival is a rallying cry for our world today

Sequences Festival unveils its 11th edition: Can’t See

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

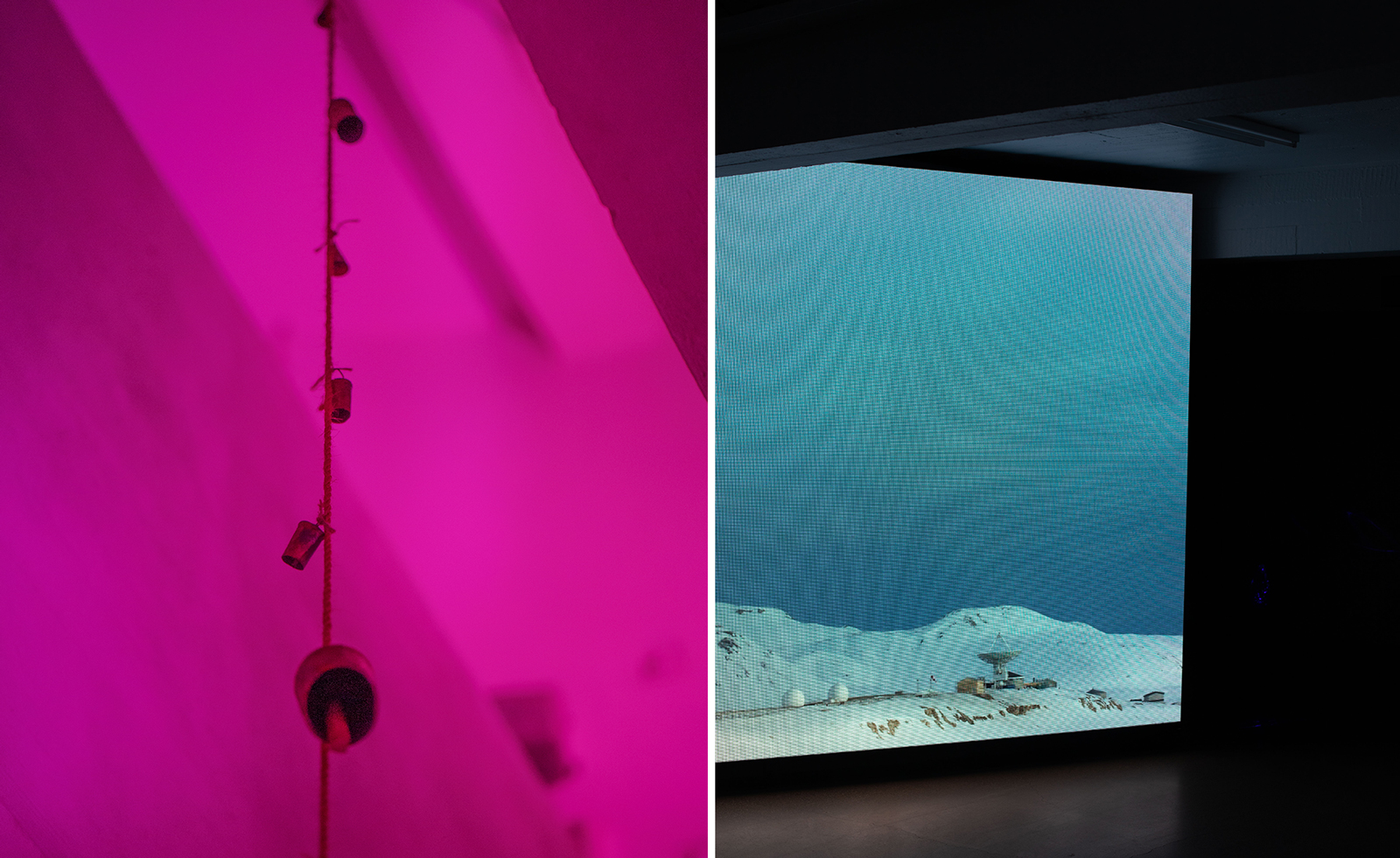

At low tide, a narrow isthmus stretches from Seltjarnarnes’ coastal road towards the Grótta lighthouse. Glossy belts of seaweed are marooned amongst shell fragments, vivid lilac against black sand. The Icelandic wind bellows, but between gusts a faint gangling is heard: the sound of many gold bells threaded on fisherman's rope; luring and jeering us towards the lighthouse. They are the intervention of artists Precious Okoyomon and Dozie Kanu, whose installation forms a jangling welcome to Sequences Festival, staged across Reykjavík’s centre, harbour and beyond.

“We wanted something low effort, but it actually ended up being intensely high-effort – installing in a windstorm”, says Kanu, between roars of icy wind. He and fellow Nigerian-American Okoyomon have strung 600 gold bells in this wind-battered place – spiralling the full height of the lighthouse and amplified by a sound-recording from the night of installation. “The work is about “being humbled by nature”, says Kanu. The bells are hypotonic, but we must return before the tide comes in, else we lose any sight of return.

Bean by Daiga Grantina_Can't See Installation view at the Living Art Museum_by Vikram Pradhan

Titled ‘Can’t See’, Sequence’s 11th edition is a rallying cry for our world: grappling with ecologies invisible, illegible or overlooked; and the existential threat that his failure of vision poses. There is no lack of conceptual vision in curation, however. Collectively, Marika Agu, Maria Arusoo, Kaarin Kivirähk and Sten Ojavee (all from the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art), have conceived of a four-chapter exhibition, plus public and performance programme, across four city institutions: Kling & Bang, the Living Art Museum (both at Marshall House), the National Gallery of Iceland and The Nordic House.

“If you can’t see, you start to damage what’s around you,” says Arusoo. Arriving at the exterior of Marshall House, the ‘Sub-Terrain’ and ‘Soil’ chapters are outlined as geological strata on from the building’s exterior, via Monika Czyzyk’s mythical window paintings – pigmented with Icelandic clay and ash – and Bjarki Bragason’s floor-to-ceiling photographic print of a doomed Sorbus tree, planted during his childhood. It seems ‘Can’t See’ has already become a lament for the soon-to-vanish, not simply the already invisible. Alma Heikkilä’s floor piece, akin to an enlarged petri dish of soil organisms, seeps and froths like the geysers and lava fields beyond. The work (flashing decaying wood (2018), is in fact in a process of being degraded by its own muddy pool. In the next room, Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir presents from her ongoing study of Surtsey island, which formed during a volcanic eruption in 1963-7 – and, too, is confronting its own erosion. Ólafsdóttir has cast a pair of footprints she discovered on the island (likely the youngest fossilised imprints on Earth); installing one at Marshall House and the other on Reykjavik's heather-strewn hinterland, where on clear days, Surtsey sharpens into view. “As soon as you go up onto the heath it’s very visible”, says Ólafsdóttir. “Once you see it, you can’t unsee it”. Yet these are the things dissolving before our very eyes; the earth in peril.

Can't See by Edith Karlson_Can't See Installation view Nordic House_ by Olof Helgadottir

Perhaps Sequences is also about attempting to ‘unsee’: or at least to see anew. Birth of a Planet (1973-4), by 20th century Latvian artist Zenta Logina is a brooding, cosmic tapestry with gold-brushed threads and a foreboding darkness. Like many of her non-conformist works in various mediums, the piece was never exhibited during her lifetime. Beloved yet also largely overlooked for her own practice was Icelandic artist and teacher Valgerður Briem (b. 1914, d. 2002). She is celebrated at The Nordic House with an enveloping wall-grid of abstract ink drawings, embracing the majesty of glacial lagoons and the wonder of Iceland Spar crystal. The festival’s visual identity, meanwhile, harnesses Briem’s typographic designs for cosmic lettering, which swirl and settle on the pages of the catalogue.

There is particular value in re-visiting the past when it resonates with the present. The National Gallery of Iceland, home to the ‘Metaphysical Realm’, unveils four lithographic ‘Map Projections’ by Agnes Denes, offering radically altered cartographies of the globe, in absurd shapes including Hotdog and Snail (both 1976). Nearby, Elo-Reet Järv’’s sculptural leather egg is titled There are Several Possible Worlds Inside The Globe, 2009, and is pierced with beckoning peek-holes. Additional sculptural works at Kling & Bang (such as Self Portrait as a Dragon, 1995), reveals the late Estonian artist as a radical reinterpreter of her nation’s heritage of leathercraft – conceiving of her creations as living organisms. Her writhing creatures are companions to Icelandic artist Olöf Nordal’s bronze Blirds (2023): morphic, skewered characters emerging from Icelandic folklore, such as Gilligogg (2023) with its swollen toes and a tiny beak, teetering on the bottom-most step at the National Gallery of Iceland.

Highlights from the darkness by Jussi Kivi_at the Living Art Museum_by Vikram Pradhan

There is whimsical, uncanny charm elsewhere. Brák Jónsdóttir’s Turritopsis jellyfish (2023), occupies the basement exhibition rooms of The Nordic House, housing the festival’s ‘Water’ chapter – apt for its pond setting, and indeed historically marred by floods. In clay and metal, Turritopsis takes its inspiration from the so-called ‘immortal jellyfish’ (named for its perplexing ability to reverse its own lifecycle). “I wanted to express the allure but also the danger of jellyfish”, says the artist, “which people sometimes forget”. Turritopsis is more hoover or spacesuit than sea-creature, with an unsettling pink lustre. Sometimes it's necessary to “abstract” the image of something “so you really see it”, says Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir (a former curator of Sequences and representing Iceland at the Venice Biennale 2024), of her own practice. “That way it goes through a cognitive process of assessment – it has to talk a walk in your brain”. Turritopsis is due to come alive during Jónsdóttir’s performance during Sequences.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Precious Okoyomon and Dozi Khanu's bells installatin at Grótta Lighthouse_Can't See Sequences XI_photo by Vikram Pradhan 2

The cognitive and the conceptual are in constant contact with the physical at Sequences. John Grzninch’s harp towers (Powerless flight, 2023, installed on the waterfront between the Edition Hotel and Harpa concert hall), is a direct translation of wind into sound, with a physicality that contradicts Benjamin Patterson’s 24-channel sound piece of spectral pond-life, invisible yet disarming in the undergrowth outside The Nordic House. Frogs don’t live on Iceland but ‘Ribbit ribbit’ it goes, recalling the ‘Chirping Drivel and Dirrd’ written alongside Olöf Nordal’s bronze Blirds. And if ever sight was to be brought into more vivid company with our other senses, Sequences gave us Edda Kristín Sigurjónsdóttir, and her Coral Living – a bus trip (part of the festival’s Real Time Art programme). On board we journeyed, past the blue mountains and wishing canyon, with lava in our pockets and pickled carrots on our plates, lulled by Ragnar Kjartansson under banana leaves and sweetened by marigold-sprinkled Icelandic chocolate, until we reached the coral-pink hills found also only on Mars, and we could barely see where we began. ‘Hringsjá’ read the hilltop waymarker sign, as we stepped off the bus close-to Ólafsdóttir’s Imprint. ‘Circle - to see’, it translates. It seems Sequences has closed the loop on its journeying for sight.