Ed Atkins selects his video-art favourites from Julia Stoschek’s 750-strong collection

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

What is ten years in the art world? Quite a while, as it turns out, when the genre is as young as time-based media (works that incorporate video, film, slide, audio or computer technologies).

The video art collector Julia Stoschek is also young, at least for someone of her standing. On 10 June she celebrated her 42nd birthday – and at the same time, the tenth anniversary of her eponymous collection in Düsseldorf. It’s one of the most significant collections of its kind. For the first time, Stoschek will be putting the curatorial reins of a show – ‘Generation Loss’ – into the hands of an artist, Ed Atkins.

Stoschek has long been an Atkins fan. She devoted a retrospective to the artist five years ago, when he was just 30 years old, and she is the most prolific collector of his video art. ‘Ed represents the generation of digital natives,’ she says. ‘Not to mention, he’s an internationally significant artist’s artist.'

Atkins selected 49 pieces from Stoschek’s collection, which comprises around 750 works in all. All the videos will be shown in the same format. The large screens are uniformly aligned, so that several works can be viewed at one glance. They are presented in choreographed sequence, and mostly in pairs. In this way, Marina Abramović and Ulay meet Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman runs in parallel to Klara Lidén, and Lutz Mommartz is shown next to 1`.

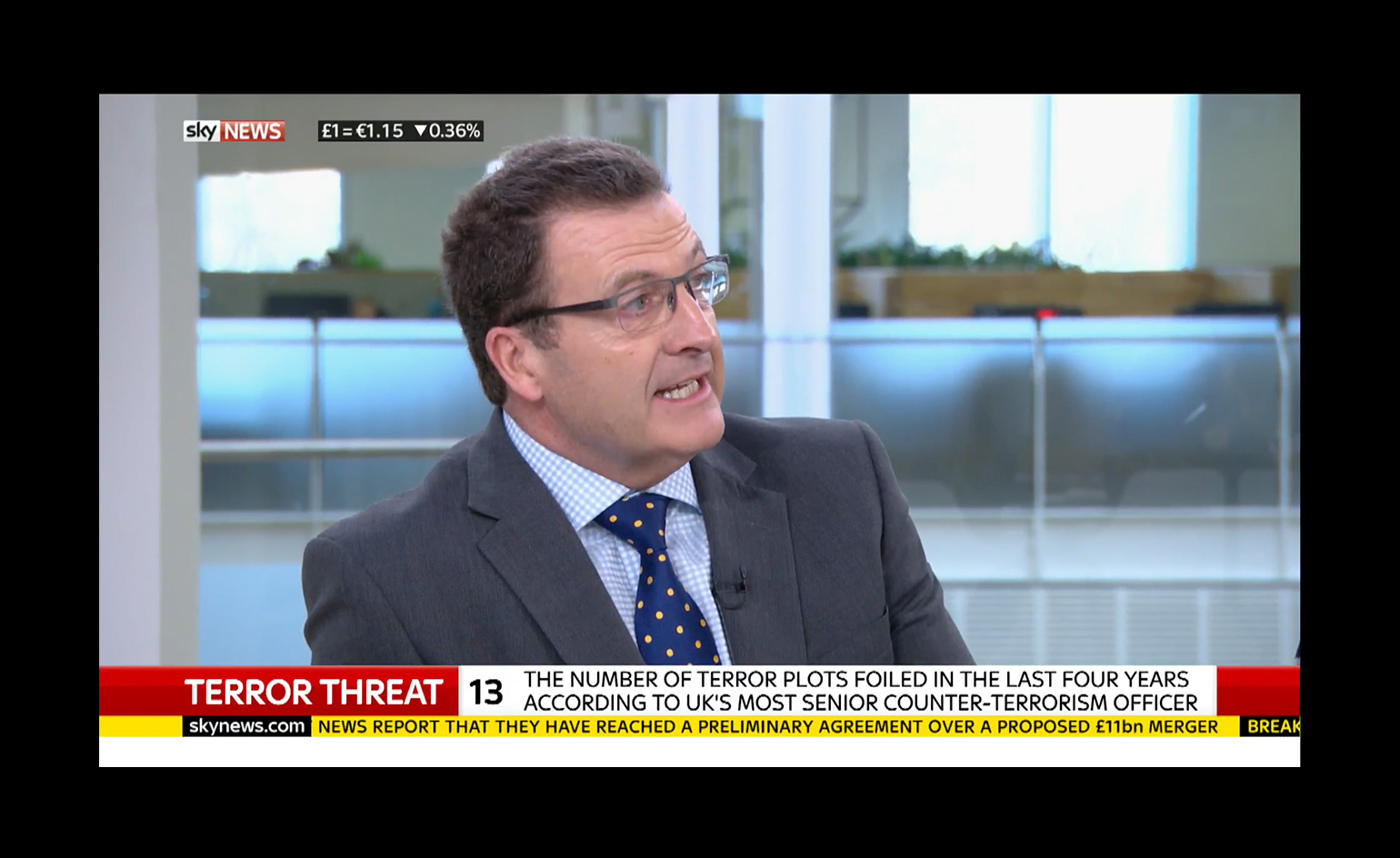

Sky News Live, by Ed Atkins and Simon Thompson, 2016. Photography: Simon Vogel

Stoschek is enthusiastic about Atkins’ concept. ‘He is giving an overview of the entire collection, creating a Gesamtkunstwerk in the process,’ she says. She was even persuaded to gut two floors of her historical building for this – acoustic glass isolates the individual works aurally, without visual separation – in an undertaking ‘comparable to constructing a new building’.

‘The exhibition is based on a community of artists, works and ideas,’ explains Atkins. ‘The communitarian form places the pieces in an intimate relationship to each other. I have a chance to temporarily suspend the hegemony of the collection, asking the words to speak in a different way; in ways they do not necessarily presume to: reflexively.’

The exhibition’s title, ‘Generation Loss’, refers to the depletion of quality that goes hand in hand with the copying or condensing of data, which is a result of evolving technologies. In curating the exhibition, Atkins found that the same reductive concept can be found in politics and culture, feelings and opinions – in short, in social change. He honed in on artistic inheritance, and the way artists enter into dialogue with their predecessors.

For artists represented in the Stoschek collection, this dialogue is very dynamic indeed. ‘There is probably no art genre that has changed so significantly over the last decade as media art,’ Stoschek concurs. ‘From analogue VHS cassettes to digital film – that was a real quantum leap. To me, apart from Gutenberg printing press, digitalisation has kicked off the largest socio-cultural shift in history.’ Accordingly, the layout of the exhibition is like a journey through time: from the beginnings of the moving image to the here and now, in which Stoschek can ‘illustrate the entire timeline of the genre’.

And what does she think the next decade holds for video art? ‘Formally speaking, I don’t think we’ll be looking at seismic changes ahead. But things are still going to stay very exciting. Soon, for example, there will be no such thing as tangible data carriers. And virtual reality, at the moment an entirely new genre, is set to evolve.’

But whatever is brewing in cyberspace – in the real world, for now, the exhibition will be showing for at least a year. ‘Time-based art needs time,’ is a dictum of the Stoschek Collection. And that is something Stoschek would also like to provide to ‘Generation Loss’.

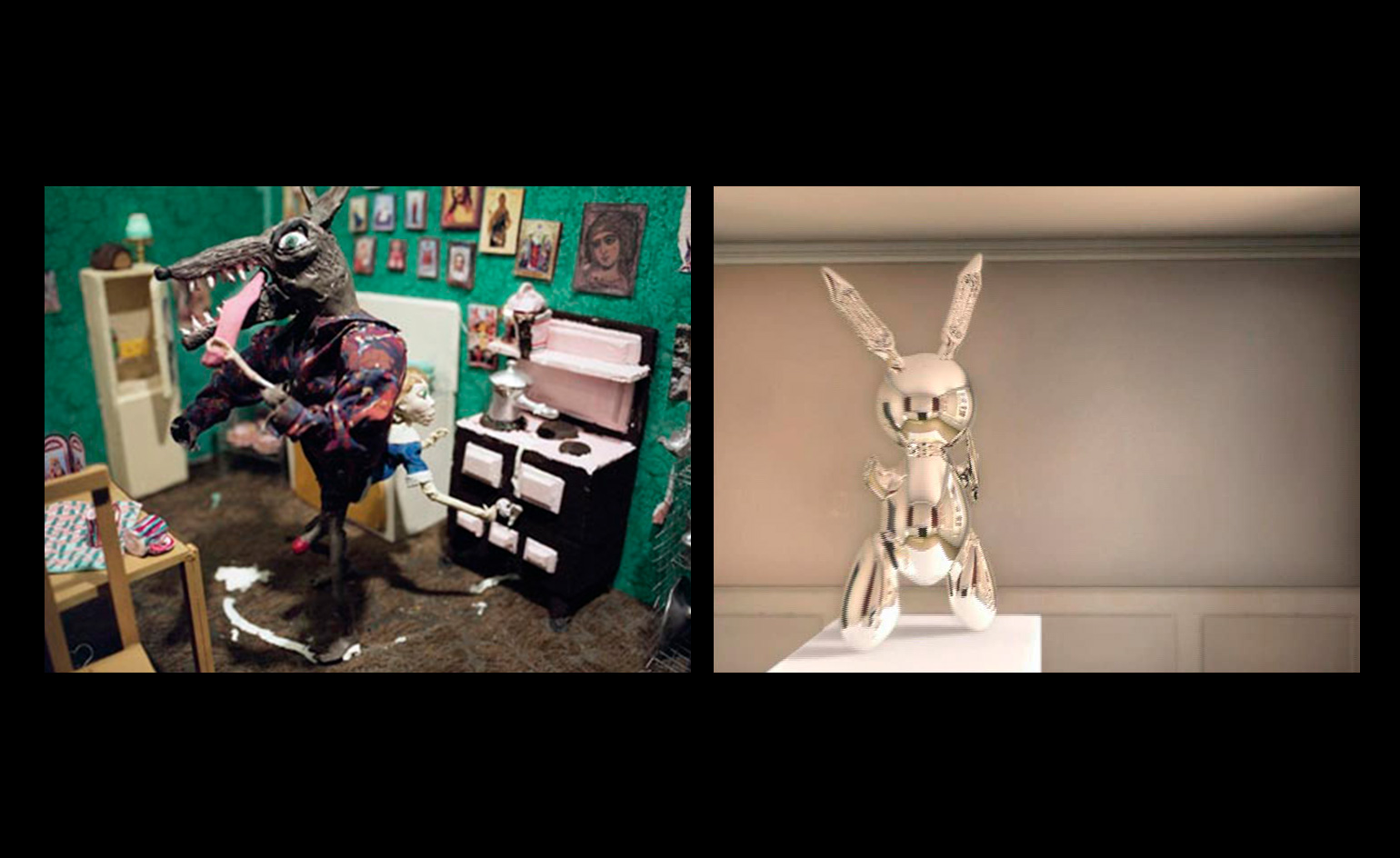

Curator Ed Atkins aligns the screens uniformly so that several works can be viewed at one glance. Left, Hail the New Puritan, by Charles Atlas, 1985-86. Right, Heartbeat / Armpit, by Wolfgang Tillmans, 2003.

Most of the art work is presented in pairs. Marina Abramović and Ulay meet Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman runs in parallel to Klara Lidén (above), and Lutz Mommartz is shown next to Paul McCarthy.

The layout of the exhibition is like a journey through time: from the beginnings of the moving image, to the here and now – such as Ian Cheng’s Emissary in the Squat of Gods (2015), a live simulation of infinite duration.

A black horizontal bar oscillates throughout Joan Jonas’ Vertical Roll (1972), bisecting the artist’s body as she appears in varied states of dress and undress.

Left, We are not two, we are one (2008) brings together clay animation by Nathalie Djurberg with a music score by Hans Berg. Right, Jeff Koons’ stainless steel balloon rabbit is the focus of Mark Leckey’s two-minute film, Made in ‘Eaven (2004).

Left, Tobias Zielony’s Le Vele di Scampia (2009) portrays a futuristic housing estate in Naples which has become a battleground for the local mafia. Right, riots during the 2001 G8 summit in Genoa inspired Bernadette Corporation’s Get rid of yourself (2006).

James Richards’ Radio at Night (2015) is a meditation on the materiality of the human body, alternating between images of eyes and mouths with those of geysers, surgical incisions and bullet holes.

Ed Atkins and Simon Thompson’s Sky News (2016) is a muted live stream of the 24-hour television news channel. The ordinary activity of watching the news thus becomes an exercise in observation and interpretation.

INFORMATION

‘Generation Loss’ is on view until 10 July 2018. For more information, visit the Julia Stoschek Collection website

ADDRESS

Julia Stoschek Collection

Schanzenstraße 54

40549 Düsseldorf

Germany

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.