The largest posthumous survey of Helen Frankenthaler puts her in the frame with Pollock and Rothko

Guggenheim Bilbao hosts 'Painting Without Rules', a major exhibition of soak-stain innovator Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings that also includes Pollock and Rothko

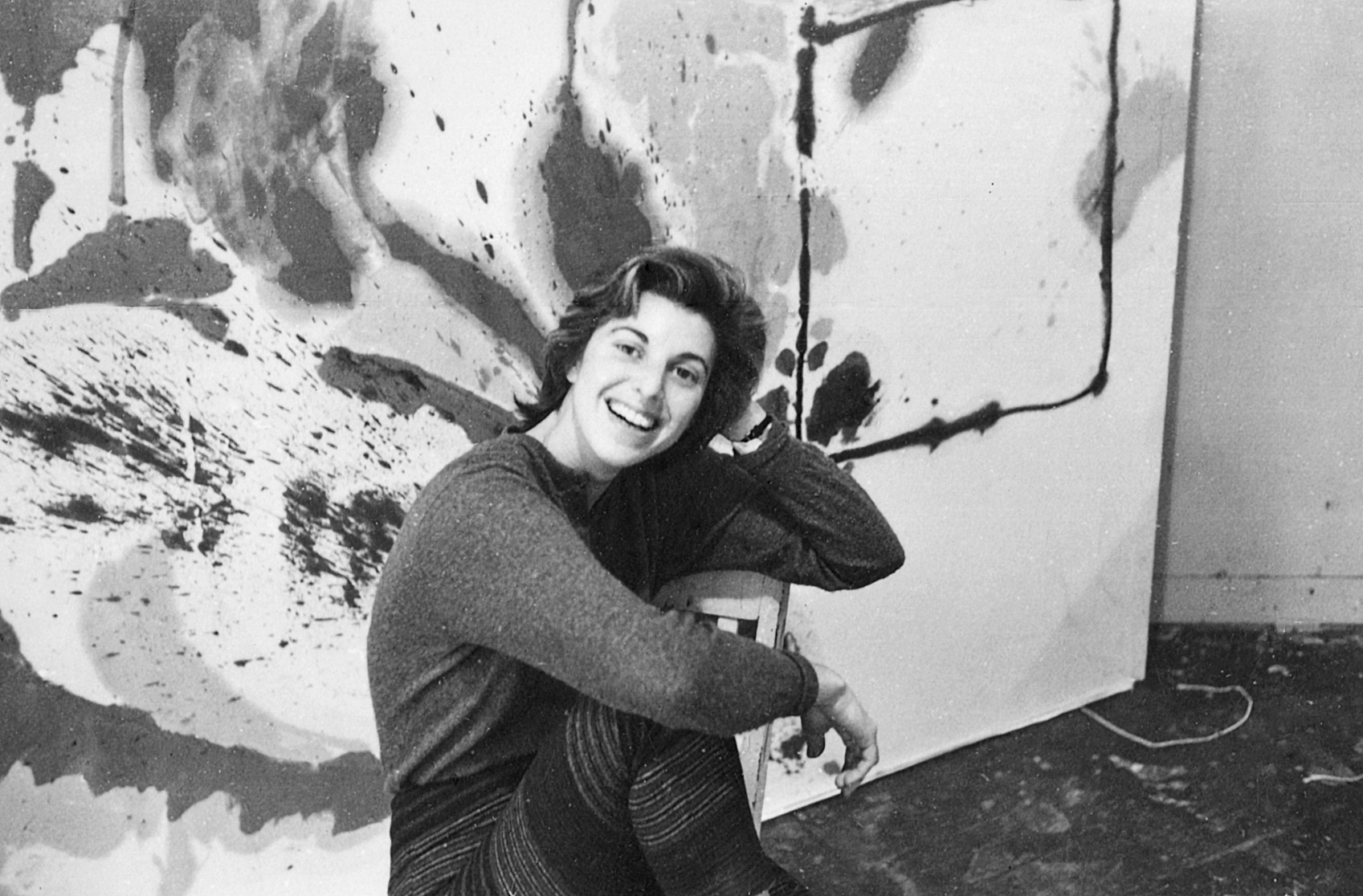

In a vintage video interview with Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), the artist says, ‘There are no rules. That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules.’ Curator Douglas Dreishpoon took this as his cue for a new exhibition, ‘Painting Without Rules’ at Guggenheim Bilbao. The show is adapted from the recent installation he composed at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, and is the first major survey of Frankenthaler’s work to be shown in Europe since her death at the age of 83.

Successful throughout her half-century-long career, with admired solo shows and museum retrospectives on both sides of the Atlantic, Frankenthaler was for a long time the only woman treated with comparable significance to her male peers in art historical scholarship on postwar abstract painting. Dreishpoon is now in the process of assembling the painter’s catalogue raisonée with her foundation, having already co-authored a book on her later works, and his intimacy with her extensive body of work can be felt in both this exhibition and its vibrant catalogue.

The rule-breaking of the title speaks to the midcentury painting revolution to which Frankenthaler contributed, alongside her fellow Abstract Expressionists and Colour Field painters, many of whom were in her closest circle. It especially reflects her individually expansive approach to the trusty canvas (usually on the floor) and on occasion to sculpture too – like the summer she bashed out ten steel pieces in a two-week stretch at her friend Anthony Caro’s London studio, following her 1971 divorce from her first husband, the painter Robert Motherwell.

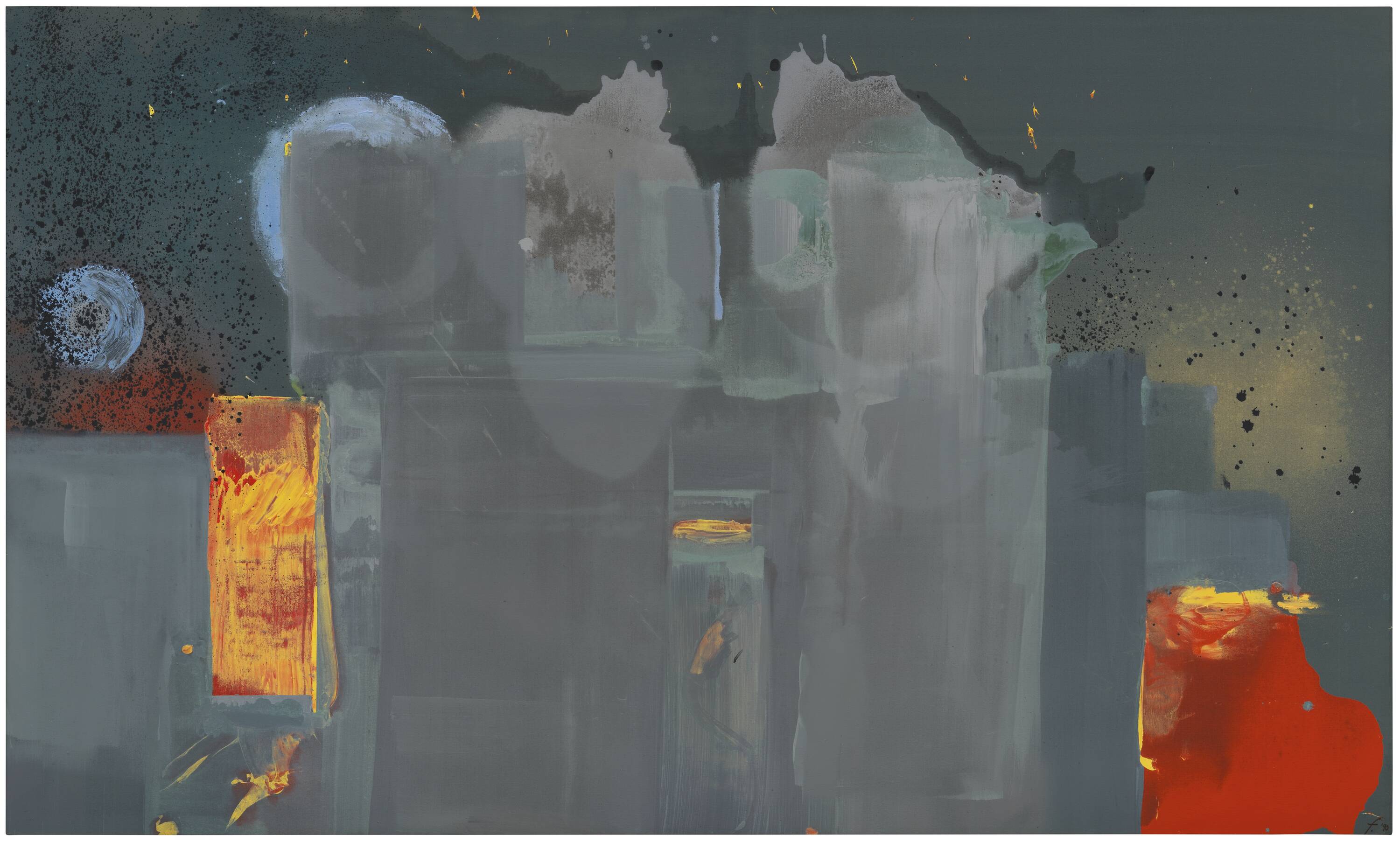

Helen Frankenthaler, Cassius, 1995

Some of these sculptures are on view at the Guggenheim Bilbao, alongside those of Caro and her close friend David Smith, who died young and whose work Frankenthaler kept near always. They’re alive and chaotic, they make sense but also don’t, and that’s a valuable insight into Frankenthaler’s paintings, which are geometric but not, organised yet imperfect, clever and wild. They’re influenced by the older, well-known painters from her coterie, including Pollock and Rothko, but they’re also not like these men’s paintings. It’s as if she absorbed elements of their methods and then expanded on them, integrating some of their techniques and evolving them into a body of work that’s transcendentally greater than the sum of its parts.

‘Painting Without Rules’ is a show about relationships, both artistic and personal, in keeping with Dreishpoon’s biographical approach to the study of art and art history. Whether or not it’s right or fair to read the work of a female artist through the lens of her personal life is a question we still need to ask, particularly when male artists are rarely framed through the lens of their relationships with key women in their lives and how those women shaped their work and ideas (unless in the problematic role of muse). Frankenthaler’s prolific career has been celebrated by numerous shows and books, but few have resisted mentioning her male connections.

What did she contribute to her ‘man painter’ friends’ work and to the history of modern art? ‘Others before her may have stained their canvases,’ says Dreishpoon, ‘but Frankenthaler’s fearless use of the soak-stain technique exploded the process of painting.’ She submerged sponges and rollers in thinned-out oil, then acrylic paint, and allowed it to soak into the fabric of monumental unprimed canvases, creating amorphous, organic-looking stains. She made her breakthrough using this method at the age of 23, in 1952, with the renowned Mountains and Sea, a work foundational to Colour Field painting and the starting point for techniques she would later explore over the years (many represented in the exhibition).

Anthony Caro, Ascending the Stairs, 1979-83

The show focuses on Frankenthaler’s relationships to guide its sequencing – not only her romantic relationships, although they are included because she took lovers and husbands from within her professional milieu, but primarily her creative relationships, with the painters, poets, critics and sculptors she lived among. Just inside the entrance we encounter Pollock’s Circumcision from 1946 ,in close proximity to Western Dream from 1957, showing how his treating painting like drawing – spontaneous, freehand, sketchy – influenced her as a young artist.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Frankenthaler said she liked Pollock’s paintings because they gave the impression ‘something had happened’. From 1959, the word ‘happenings’ started being used to describe a less formal style of art-related event that was emerging. It spoke to a dynamic, living art, a scene animated by spontaneity and social connection. Something happened in Frankenthaler’s paintings too – something dramatic and expressive, something somatic, to expand the often-used word ‘gestural’ to include the whole body and being into how she approached action painting.

Dreishpoon brings up the emergence of New York’s postwar downtown vernacular when he points out the artist’s recurrent square motif. ‘Square’ as opposed to ‘hip’. An uptown girl living a downtown bohemian life, Frankenthaler was both. In her work, squares repeatedly intersect with, yet rarely contain, various flowing, entangled forms. The curator reads them as representing the way that certain structures – maybe a marriage or societal expectations – come into play with the freeform chaos of life.

Frankenthaler was born to a ‘good Jewish family’ on the Upper East Side, and was given financial support, education, and confidence. She grew up in a privileged environment but suffered from the loss of her father at the age of 11. She had solo shows at respected galleries and was curated into era-defining group shows. Her first retrospective, at the Jewish Museum in 1960, was curated by the poet Frank O’Hara.

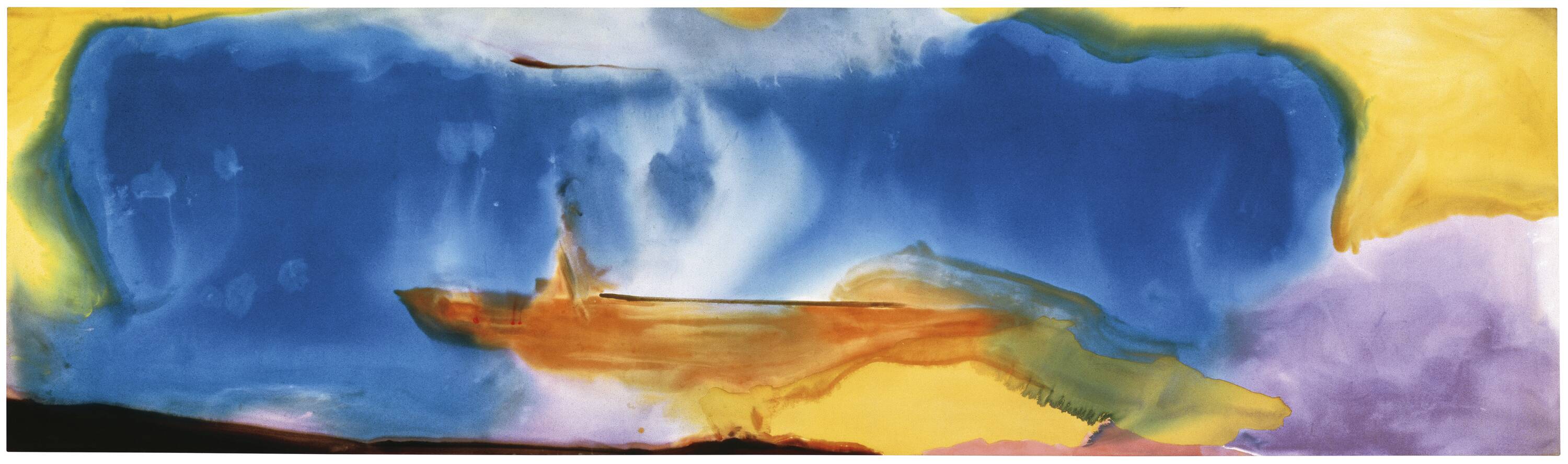

Helen Frankenthaler, Star Gazing, 1989

The Upper East Side townhouse she shared with Motherwell hosted numerous parties and was photographed for an article in Vogue. A blow-up featuring a Rothko over the mantlepiece, between a painting by her and another by her husband, compellingly takes up one wall in the exhibition. The art director of American Vogue, Alexander Liberman, was a close friend. A great painter, yes, and simultaneously a socialite. Like everyone who’s ever had a big career, Frankenthaler was unapologetically ambitious.

One of her early boyfriends, Clement Greenberg (twice her age and considered by some to be last century’s most influential art critic) once said, in front of Frankenthaler and another woman painter, Lee Krasner, that there would never be a great woman artist. Not long afterwards, Frankenthaler painted Scene With Nude, controversial in 1950s America, especially for a young woman. It contains what some see as an inference towards ‘splayed thighs’, which her biographer, Mary Gabriel, suggests was a taunt in response to Greenberg’s gender bias.

Fighting her corner in a misogynist climate, the artist was reluctant to be known as a woman painter, and declined invitations from places like then-new and now-cult downtown femme gallery A.I.R. As for any woman of her generation, especially one with a career, assimilating to aspects of machismo was essential for survival.

Helen Frankenthaler, Janus, 1990

Frankenthaler’s freedom in painting was correctly interpreted as transgressive, even by some of her peers. She left the camaraderie of her first gallery because some of the feedback was so cutting. Opinions could be similarly hostile at times later on, but by then she’d grown a thicker skin. Her work is often praised for its formal beauty, through criteria initially laid out by Greenberg, in an effort to protect artists from being targeted for their beliefs at a time when, like now, the New York police and CIA were punishing and paranoid. Postwar abstraction was a form of resistance, against legibility (important politically) and cliché (important aesthetically).

Dreishpoon opens the door to interpretive readings of some of the 1970s paintings, which he describes as ‘provocative and enigmatic’: birth canal-like passageways harbouring floating forms suggest the anatomy of a female body that synchronised with feminism’s rise in the US and womens’ rights with Roe v Wade. They also synched with her divorce, the divorces of many friends, and some of their abortions.

In the 1970s section of ‘Painting Without Rules’, we see Frankthaler painting landscape-like forms: bluescapes with blood red and skin tone strikes across them; sandy yellow waves like aerial view coastlines with black lines that could be… Hairs? Cuts? Boundary crossings? There’s a human scale red-stained figure in the water held down by a straight line, with red dots at the mouth and throat. The paintings are huge. Specifics remain out of reach.

Helen Frankenthaler, Moveable Blue, 1973

Abstraction thrives on ambiguity. Frankenthaler loved that about it. It is also inherently embodied and emotional, despite art criticism’s best efforts to post-rationalise it as an intellectual position. The ways in which the most celebrated abstract paintings were made, including hers, weren’t necessarily abstract acts, intellectually generated. The word ‘abstraction’ implies that an idea comes first, and is then departed from. Frankenthaler didn’t work like that. Creative impulse channelled through her automatically – that’s where her genius comes into play.

Frankenthaler was well-read and a prolific writer. Her seriosity didn’t constrain her, though. So at ease was she in her seriousness, she wasn’t afraid to mix it with emotionality and elementality, or to lighten it with humour. Her work’s expansiveness, its depth of character, reflects this complexity. As Dreishpoon puts it, ‘An artist unconstrained by rules can be whatever she wanted to be at any given moment. Frankenthaler’s notion of beauty, never cosmetic, was as complicated as the human condition.’

'Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules' is at Guggenheim Bilbao until 28 September 2025

Helen Frankenthaler, Open Wall, 1953

Kasia Maciejowska is a writer and editor covering arts and culture. Her first book The House of Beauty and Culture (ICA, 2016) was about a radical London crafts collective, and she’s currently working on a monograph about Moroccan-French photographer Leila Alaoui (Skira, 2026). Consultancy clients include museums, galleries, design studios, and futures agencies. She also runs a creative career mentoring network for young refugee women