Don’t miss: Hayv Kahraman intertwines colonialism and botany in London

Artist Hayv Kahraman draws parallels between colonial botany and her experiences as an Iraqi refugee transplanted into Europe, at Pilar Corrias in London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

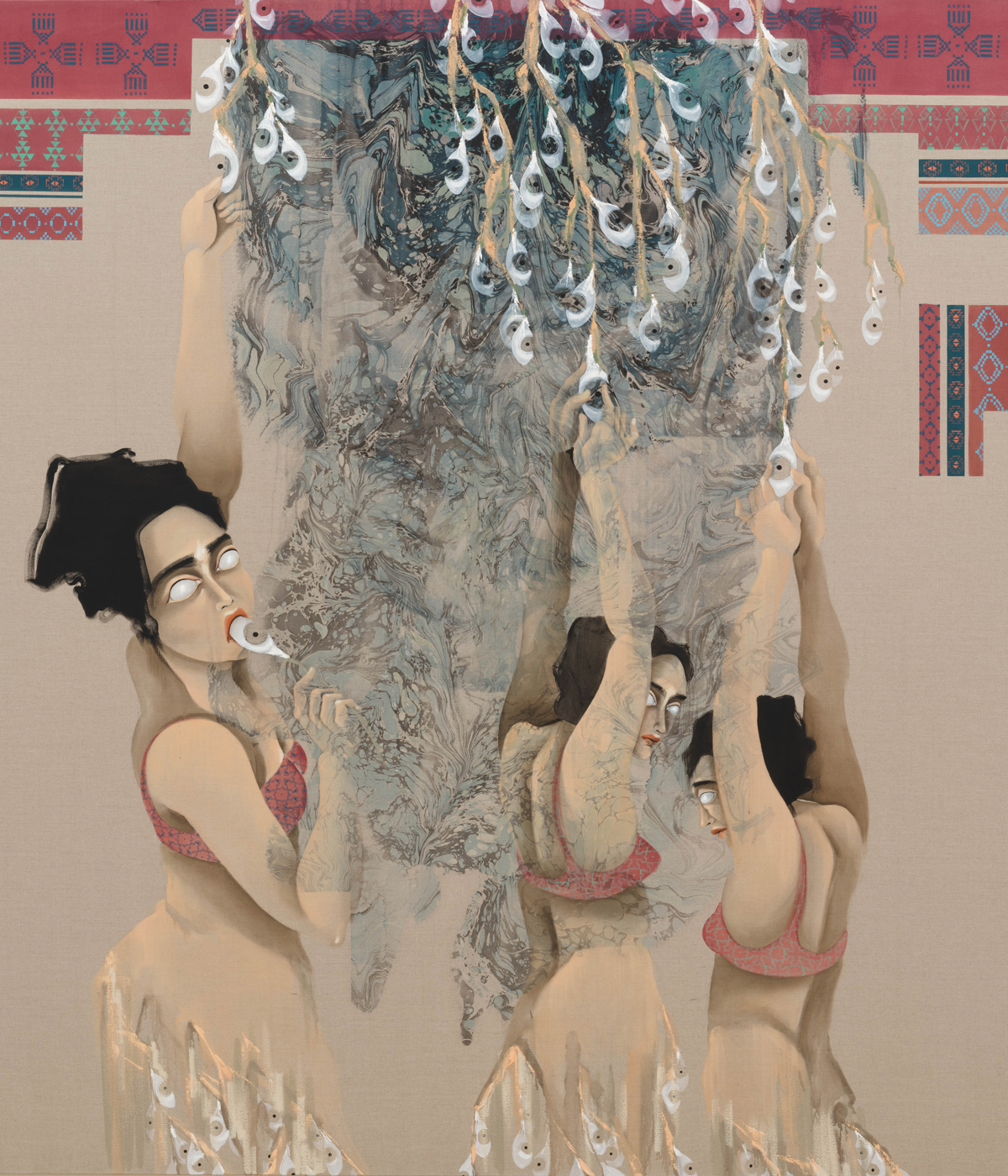

As an Iraqi refugee growing up in Sweden, artist Hayv Kahraman absorbed the teachings of 18th-century Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus. Famed for his habit of transporting plants from around the world into Europe and for his system of reclassifying them with genus and species names, in Latin, he and his colonialist experiments became an inextricable part of Swedish identity for Kahraman, who saw parallels with her struggles to assimilate in a new country. In artworks by Hayv, who is now based in Los Angeles, these botanical references become synonymous with the idea of the Other. The painted forms of figures become dreamlike symbols, juxtaposed against diaphanous, dreamlike clouds of marbling.

We talked to the artist about the story behind her works.

Hayv Kahraman on reframing the narrative at Pilar Corrias in London

Hayv Kahraman, Eye-dates, 2024

Wallpaper*: By considering the colonial implications in a single piece of work, you embrace a juxtaposition of artistic forms and cultural references. Can you tell us why Linnaeus' work was so clearly meriting attention for you?

Hayv Kahraman: When I started my schooling in Sweden, I was taught that Carl Linnaeus was a genius and a heroic figure. He was on the 100 Krona bill, and I remember visiting his herbarium in Uppsala during a school field trip. Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist who lived in the 18th century. His taxonomic contributions to the natural sciences by means of collecting plants from elsewhere, bringing them back to Europe and renaming them into his latinised binomial nomenclature, contributed to erasing the indigenous histories surrounding that plant. These colonial practices of renaming flowers and plants, a vocabulary that centered the white European heteronormative man (most famously Linnaeus) and propelled nationalistic, eugenic and nativist pulses into botany were crucial in the expansion of empire.

But what irked me the most as I was researching, was his incessant urge to ‘acclimatize’ certain plants to the Swedish climate, which of course utterly failed. I am here reminded of the potent assimilation process I underwent in Sweden as a newly arrived Iraqi refugee back in the 1990s. How I was taught to think like a ‘Swede’, to act like a ‘Swede’ in order to be worthy of staying in that country. And it is this feeling of indignation that fuelled the work. I needed to unpack his volatile legacy, and then find alternative ways of sensing the world in which hope can be found.

Hayv Kahraman, Generational Eyebrows, 2024

W*: By taking control of techniques with roots in other societies, such as marbling, how did you celebrate a new perspective, separate from the historical implications?

HK: My interest in marbling started when I went to the Huntington Library in California to actually see/open/touch/feel one of Linnaeus’ books, and as I flipped open the cover I saw a marbled front piece and knew that I needed to look into this art form. Marbling has a long history, starting in Japan, travelling to central and west Asia and then Europe. It was used in the Ottoman region on legal documents to prevent forgery. Historical implications aside, I found it fascinating that an art medium was used to prevent appropriation, that it's a mono print that cannot be duplicated/appropriated/forged because of its incredible unpredictability.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

What turned things for me personally, though, was when I actually started marbling and experimenting in my studio. I found the process incredibly therapeutic.

[Not] being concerned about how things will ‘look’/ how things will be ‘perceived’/how legible/ knowable the work will be – it allows me to not categorise, to not order things, to break away from that kind of thinking that I’ve been plagued by since I became a refugee in Europe. I found that there’s an acceptance that happens in this process. An acceptance of the flow and movement of life somehow. And as a survivor of domestic violence, relinquishing control can be incredibly difficult, but marbling feels freeing. As if paving a way to heal.

Installation view, ‘Hayv Kahraman: She has no name’, Pilar Corrias, London

W*: The works themselves marry these techniques with powerful proportions that make strong female figures central. How did your process inform this otherworldly narrative?

HK: The figure, the body, has always been a means for me to negotiate things around me. I studied ballet in Baghdad at a very young age and since then I’ve always composed choreographies of bodies in my mind. I think of the figures as snapshots in my paintings. They are caught in an act of performing something. A doing and an undoing of something. They’ve become my methodology to think through difficult topics, such as colonial botany in this instance.

'She Has No Name' is at Pilar Corrias, London, until 25 May 2024

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.