The cultural weight of girlhood is complex and beautiful at MoMu

A new Antwerp exhibition, ‘Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’, frames girlhood as both archetype and subversion, featuring works by Sofia Coppola, Louise Bourgeois, and more

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Through the lens of American filmmaker Sofia Coppola, girlhood appears dreamlike yet tinged with melancholy; her intricate coming-of-age stories are softened by honey-lit portrayals of enigmatic characters. By contrast, French-American artist Louise Bourgeois channels something far more cathartic: her work is a dark allegory of gendered oppression, shaped by the searing memories of an alienating childhood. Japanese photographer Fumiko Imano, meanwhile, strikes a more playful register with self-portraits alongside her imagined twin: a tender, gregarious meditation on youth refracted through cultural dissonance.

Fumiko Imano, Yellow bath/Hitachi/Japan, 2007

The truth is, girlhood resists definition. It is at once singular and collective. Glimpses of it surface in art and in memory. It informs who we are, but more often than not, we want to rebel against it. It is complex, but it’s also beautiful.

In ‘Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’, showing until 1 February 2026 at MoMu, Antwerp’s fashion museum, girlhood is framed less as an answer than as an open question. Curator Elisa De Wyngaert describes it as ‘delicate, subversive, volatile and unresolved’. She admits to a flicker of anxiety about how audiences might respond, whether the binary boundaries of the word will be challenged. ‘I keep reminding myself that girls deserve this space,’ she says.

Knitted bikini top and shorts set, worn by the actress Kirsten Dunst in The Virgin Suicides, 1999, Sofia Coppola’s film adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ 1993 novel

The exhibition poses questions rather than offering conclusions: ‘When do you stop being a girl? Is it a choice you make, or made for you? Is girlhood just a phase, or something more lasting: a mindset, a feeling, an aura you carry? Which memories, emotions, or impulses stay with you, shaping who you become?’

‘Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’ at MoMu

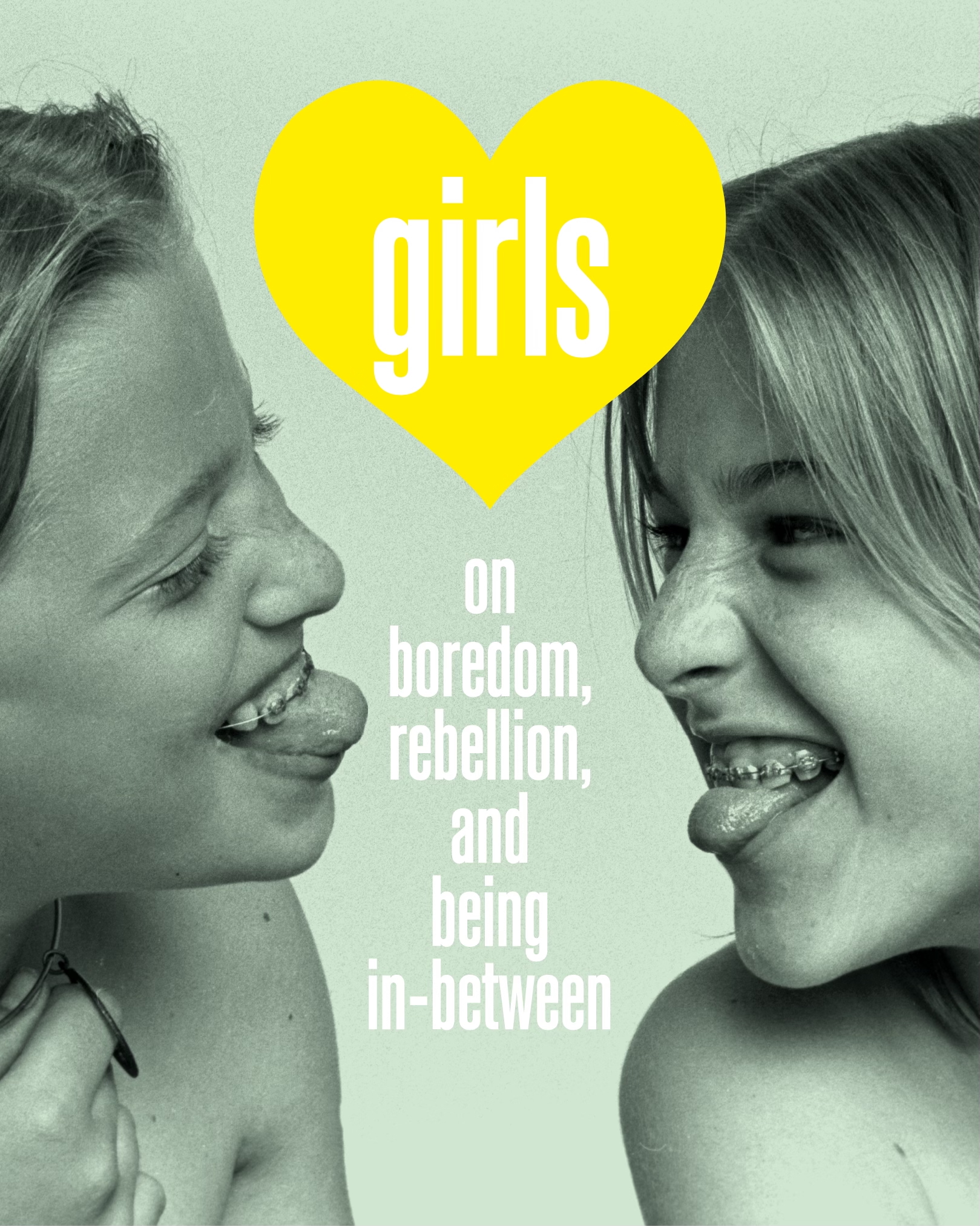

The show's poster, featuring photographer Jim Britt’s Sisters, 1976, and graphic design by Paul Boudens

Themes such as ‘the lingering years of girlhood’, ‘boredom’, and ‘coming of age’ are traced through the exhibition's constellation of works across art, fashion, film, and photography. It is a relevant and timely field study, especially since, in the last five years, social media has repackaged girlhood into a stream of micro-trends and endless vocabulary: girl dinner, girl walks, girl maths. It feels apt, then, that the exhibition opens with Maya Man’s Love/hate (2022): a punching bag cradling a phone that scrolls endlessly through gendered performance in the theatre of internet culture. From this starting point, the show unravels the sartorial, iconographic, cultural and psychological associations tethered to the figure of the girl.

Micaiah Carter, Adeline in Barrettes, 2018

For much of art history, the female subject was cast as a passive subject. Only in the late 20th century did its portrayals begin to carry emotional and psychological depth, paralleling the emergence of distinctly gendered children’s fashion.

Japanese-Mongolian painter Arisa Yoshioka frames growing up as an ongoing negotiation of belonging, while Nathanaëlle Herbelin’s Charlotte (2023) captures her neighbour’s fragile courage in choosing whether to present as a boy or a girl. American artist Alice Neel’s Memories (1981) offers a piercing portrait of her only surviving daughter: an image that confronts the turbulence of balancing young motherhood with the demands of an artistic career. Meanwhile, Italian fashion stylist and visual artist Sofia Lai’s morphing sculptures embody the bodily anxieties of growing up.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Sofia Lai, Burden: The Dollhouse, 2025

The theme of sleep is central here. Bedrooms, after all, often mirror the intensity and fragility of adolescence. Within the exhibition, three rooms are reimagined as installations, each evoking a different form of yearning, whether for shelter or escape.

The first references Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999): Lux Lisbon’s clothes are scattered across the bed, a stark contrast between the shapeless, conservative feedsack dresses enforced under parental watch and the clandestine outfits meant for nights out.

Taiwanese designer Jen-Fan Shueh, of Jenny Fax, reconstructs her own teenage bedroom: an austere space defined less by her desires than by her mother’s vision, notable in its absence of clutter. The final room, created by Emma Chopova and Laura Lowena of Chopova Lowena, draws on their Bulgarian-American and British heritage.

Jenny Fax’s installation in ‘Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’ at MoMu – Fashion Museum Antwerp, 2025

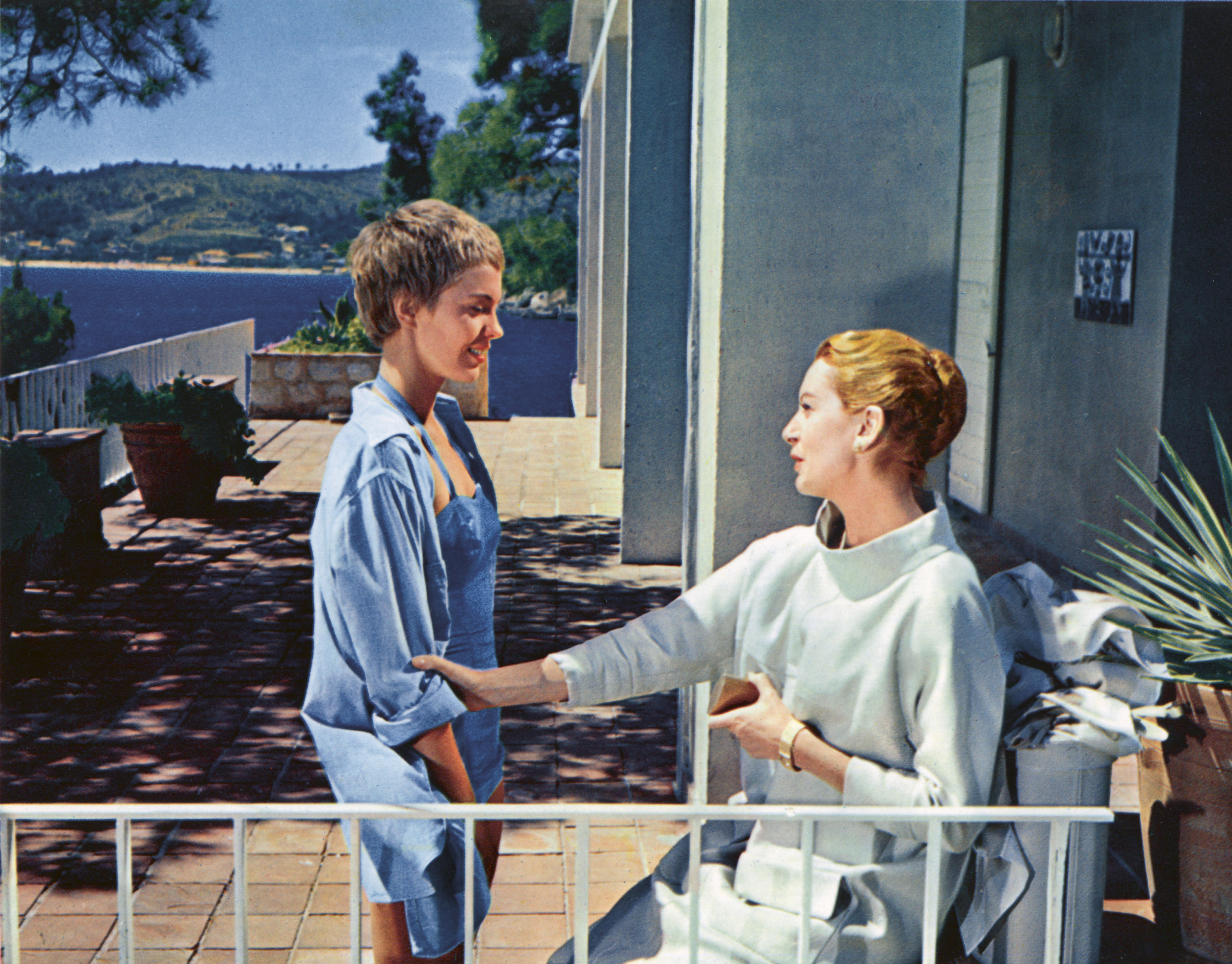

Guest curator Claire Marie Healey brings a cinematic lens to the exhibition, selecting films that lend the theme a vivid, visual dimension. Works such as Marie Antoinette (2006), Girlhood (2014), and Bonjour Tristesse (2024) challenge cinema’s patriarchal gaze, portraying restless, resilient characters who resist containment. This leads into ‘Picturing girls’, a section that spotlights three photographic narratives shifting between documentary, portraiture, and autobiography.

Jean Seberg and Deborah Kerr in Bonjour Tristesse, directed by Otto Preminger based on the novel by Françoise Sagan, 1958

Rituals of girlhood emerge as recurring motifs. In Girls Shopping (2001), British-American photographer Nancy Honey captures the simple joy of an adolescent outing: ‘They didn’t buy much that day – they tried on endless pairs of shoes and clothes and ate sweets. That was the joy of it,’ she recalls. By contrast, Leticia Valverdes’ Brazilian Street Girls (2000) reflects her lifelong commitment to documenting those on the margins of society, while Eimear Lynch’s Girls’ Nights (2023) traces the charged anticipation of Irish teens preparing for discos.

Eimear Lynch, Girls’ Night, 2023

Archival works also resonate. Jim Britt’s Sisters (1970s) and Nigel Shafran’s Teenage Precinct Shoppers (1990) occupy a special place, alongside zines (notably Bikini Kill, Riot Grrrl, and Femzine) that summon memories of collaging teenage icons, riot slogans, and anti-commercial mantras. A curated library of texts extends the dialogue; literary volumes by Sylvia Plath, Simone de Beauvoir, and Bernardine Evaristo offer new ways of mapping girlhood’s elastic borders.

‘The way girls are dressed in art, fashion, film, and photography is a language in itself. It reveals much about the assumptions projected onto girlhood and its place in society’

Elisa De Wyngaert, curator at MoMu

Increasingly, in the realm of fashion, female designers have reclaimed archetypes and paraphernalia linked to the hyper-girly figure, which were once dismissed as infantilising: white socks, hair slides, glitter, nail art, hoodies. Case studies include how Simone Rocha reframes communion as a ritual of dress, Veronique Branquinho reimagines the prom queen and the schoolgirl, and Molly Goddard draws on the silhouettes, textures, and playfulness of childhood clothing. Earlier examples include Miuccia Prada’s ambiguous renderings of girlhood through both Prada and Miu Miu, and Maison Martin Margiela’s 1992 Artisanal collection, which deconstructed 1950s debutante gowns. ‘Perhaps it’s a way for designers to go back to their own adolescence,’ De Wyngaert suggests.

Ashley Williams, Spring-Summer 2025

Wales Bonner, Autumn-Winter 2023-2024, Mary Janes

‘Girls’ concludes with a museum-produced film: a focus group of women across generations, each offering an intimate reflection on girlhood. Leaving the exhibition, it’s hard not to recall that scene in The Virgin Suicides, when the doctor tells young Cecilia, ‘You’re not even old enough to know how bad life gets,’ and she quips back, ‘Obviously, Doctor, you’ve never been a 13-year-old girl.’ At MoMu, ‘Girls’ is brilliant at capturing – or reminding us of – exactly that.

Jim Britt, Sisters, 1976

‘Girls. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between will be on display at MoMu until 1 February 2026. For more information, visit momu.be

Sofia de la Cruz is the Travel Editor at Wallpaper*. A self-declared flâneuse, she feels most inspired when taking the role of a cultural observer – chronicling the essence of cities and remote corners through their nuances, rituals, and people. Her work lives at the intersection of art, design, and culture, often shaped by conversations with the photographers who capture these worlds through their lens.