Bill Viola/Michelangelo: a meditation on mortality and revival at the Royal Academy

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In the Royal Academy’s new exhibition ‘Life, Death Rebirth’ that seams American video artist Bill Viola with Renaissance doyen Michelangelo, a drawing by the latter, etched 487 years ago, depicts the punishment of the mythical giant Tityus. The giant’s muscle-hewn body was chained to a rock by Hades, the Greek god of the underworld. Each day, Hades would set a vulture loose on Tityus’ exposed body. The vulture would rip out and eat his liver – ‘the seat of lust’. At night, Tityus’ liver would grow back. Each morning, the vulture would begin again. The torment, Hades decreed, would last for eternity.

Next to Tityus stands an etching of Hercules, who, in a fit of madness, killed his wife and children. In return for freeing him of his guilt, the Gods tasked Hercules with 12 seemingly impossible tasks. Michelangelo depicts the slaying of the Nemean lion, whose coat was impervious to arrows. Hercules strangled the lion to death after breaking its fanged jaw with his bare hands.

Michelangelo was 52 when he presented the drawings as a gift – something akin to a love letter – to the teenage Roman aristocrat Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, with whom he had become infatuated. The Italian artist distinguished between two kinds of love: a wild, carnal lust that can drive us to destruction, and a spiritual, divine love that can lift us towards God.

Three Labours of Hercules, c 1530, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, red chalk. Courtesy of Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The drawings are on display in a London exhibition that at first glance depicts a tenuous union. One is the great master of the Renaissance. The other a contemporary artist from New York who creates video installations that can at times veer between something resembling Michael Haneke, Lars Von Trier and a mobile phone advert. The pairing of Viola and Michelangelo is not, co-curator Martin Clayton insists, an attempt to suggest the two artists should be placed on a comparable pedestal. ‘They are not somehow equals,’ said Clayton during an introductory speech.

Instead, the curator hopes to create a dialogue – ‘a conversation across five centuries’ – between the themes and philosophies that drove the two artists. Namely, the uncertainty of life and the tantalising possibility we may be more than mere flesh. When we think of Michelangelo now, we think of him as the painter of the Sistine Chapel and the sculptor of huge figures,’ Clayton writes in the exhibition’s catalogue. ‘The emotional and spiritual intent of his work has largely left our understanding, yet for him that was the most important thing.’

Opposite Tityus stands two slabs of granite. On each slab is projected an ageing man and a woman. Both are naked, and are engaged, slowly and methodically, in passing a torch over their bodies. They are searching for blemishes, imperfections or illness. Eventually, Viola has them turn off their torches, and dissolve slowly into dust.

Fire Angel, panel 3 from Five Angels for the Millennium, 2001, by Bill Viola, video/sound installation. Performer: Josh Coxx. Courtesy of Bill Viola Studio.

Earlier in the exhibition, and stood opposite Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo marble relief (c 1504-1505), plays Viola’s Nantes Triptych (1992). On the left, a young woman is splayed across the edge of a bed in the process of giving birth. On the right, an old woman – Viola’s own mother, it turns out – is lying motionless and barely breathing. One is dying, the other is in the midst of creating life, sweating, struggling and crying. In the final room, we witness the silhouette of a woman standing before a wall of wire, before falling into the dark water of an unseen pool.

In the corner of one of the gallery rooms, I speak to Kira Perov – executive director of Viola’s studio and his wife of 30 years – at the private view of the exhibition. The couple met in 1977 when Perov was the director of cultural activities at La Trobe University in Melbourne. She invited Viola over from the US to show in an exhibition of video art. What kind of person is Bill Viola to those that don’t know him, I ask.

‘Bill realised at a certain point that his life is his art,’ she says. ‘That's really what he is. This work is indistinguishable from him. We’ve had a lot of adventures together as a result. All that adds up: it becomes experience and it becomes knowledge and maturity and understanding. He’s a brilliant mind... someone who believes deeply in asking, through his work, what life is, and how am I going to pass through it.’

But does the comparison Clayton and Perov make work, once the creations of these two artists are breathing together in the same room? For if their is a kinship in the artists’ philosophies, then there is little doubt that the tone of their works is totally divergent.

‘Bill realised at a certain point that his life is his art. That’s really what he is. This work is indistinguishable from him.’

There’s something merciless about video art, particularly at this high-definition scale, in the enveloping quiet dark of the RA’s halls. Witnessing the beings that people Viola’s art can often feel strangely voyeuristic. In the case of the ageing couple with the torches, the act of viewing can feel crass, particularly when one can turn and consider the grainless and smooth curves of The Virgin and Her Child, carved from a single piece of marble, or the presence of the mythic Tityus and Hercules and the eternal beasts they battle with.

Yet Viola’s work has an undeniable potency. Stand in front of that granite, and try not to think of how we all make a prison of our bodies, worry for its failings, judge its imperfections. Reflect on this, and suddenly the vultures talons that dig into Tityus are longer. Its eyes are keener, its beak sharper. The lion’s coat is heavier, its despair as Hercules finally overpowers it, somehow more evident.

Against the slow-moving spectacle of Viola, Michelangelo’s chalk and charcoal becomes even more vibrant, the preoccupations of his life even more eternal. Michelangelo’s Tityus and Hercules is not just an exquisite artefact from the past, not just something to admire, but something that can be felt deep within our darkest selves. For we are all in time and of time. And we all cling, secretly, to the same hope: that we might not end, but be reborn.

The Dreamers, 2013, by Bill Viola, video/sound installation. Performers: Gleb Kaminer, Rebekah Rife, Mark Ofugi, Madison Corn, Sharon Ferguson, Christian Vincent, Katherine McKalip. Courtesy of Bill Viola Studio.

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c 1540, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, black chalk. Courtesy of The British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum

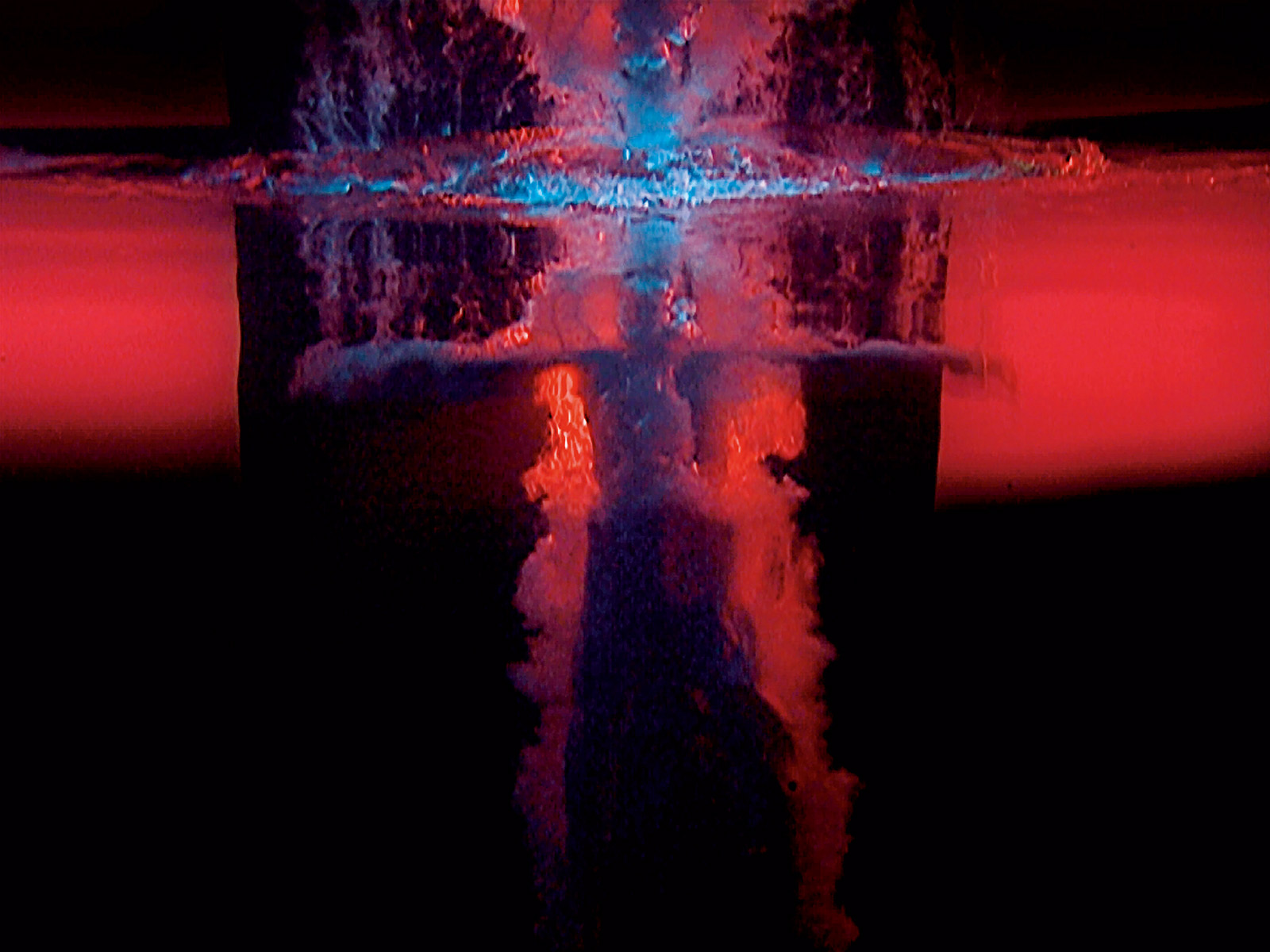

Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall), 2005, by Bill Viola, video/sound installation. Performer: John Hay. Courtesy of Bill Viola Studio.

INFORMATION

‘Bill Viola / Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth’ is on view from 26 January – 31 March. For more information, visit the Royal Academy website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Royal Academy

Burlington House

London W1J 0BD

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.