Animal roar: Bernie Krause's carnal orchestra at Fondation Cartier, Paris

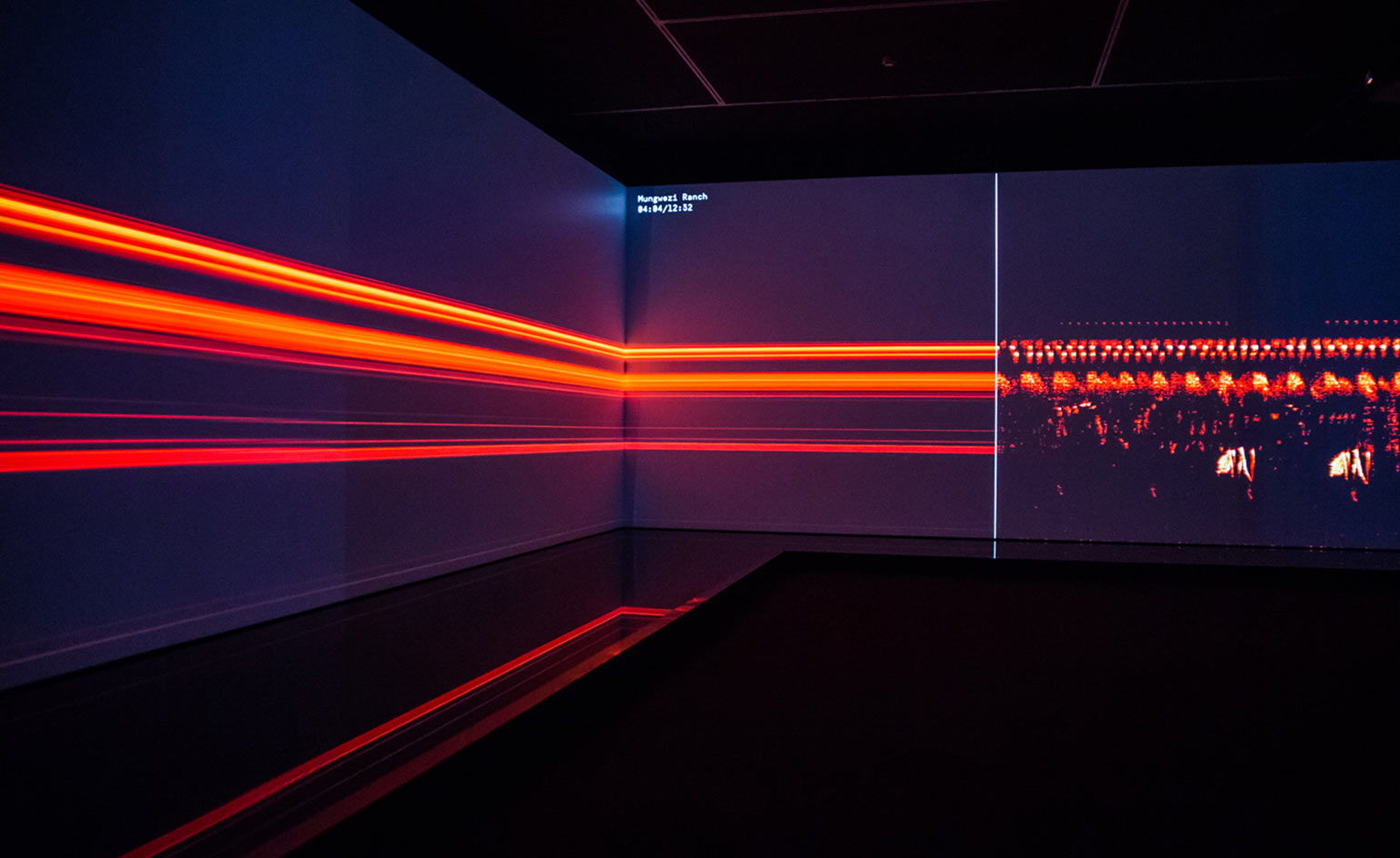

Conductor, long-time musician and recording engineer Bernie Krause presents a new exhibition and sound installation at Fondation Cartier in Paris. With 'The Great Animal Orchestra', his scientific work is repositioned within an artistic construct. Pictured: installation view.

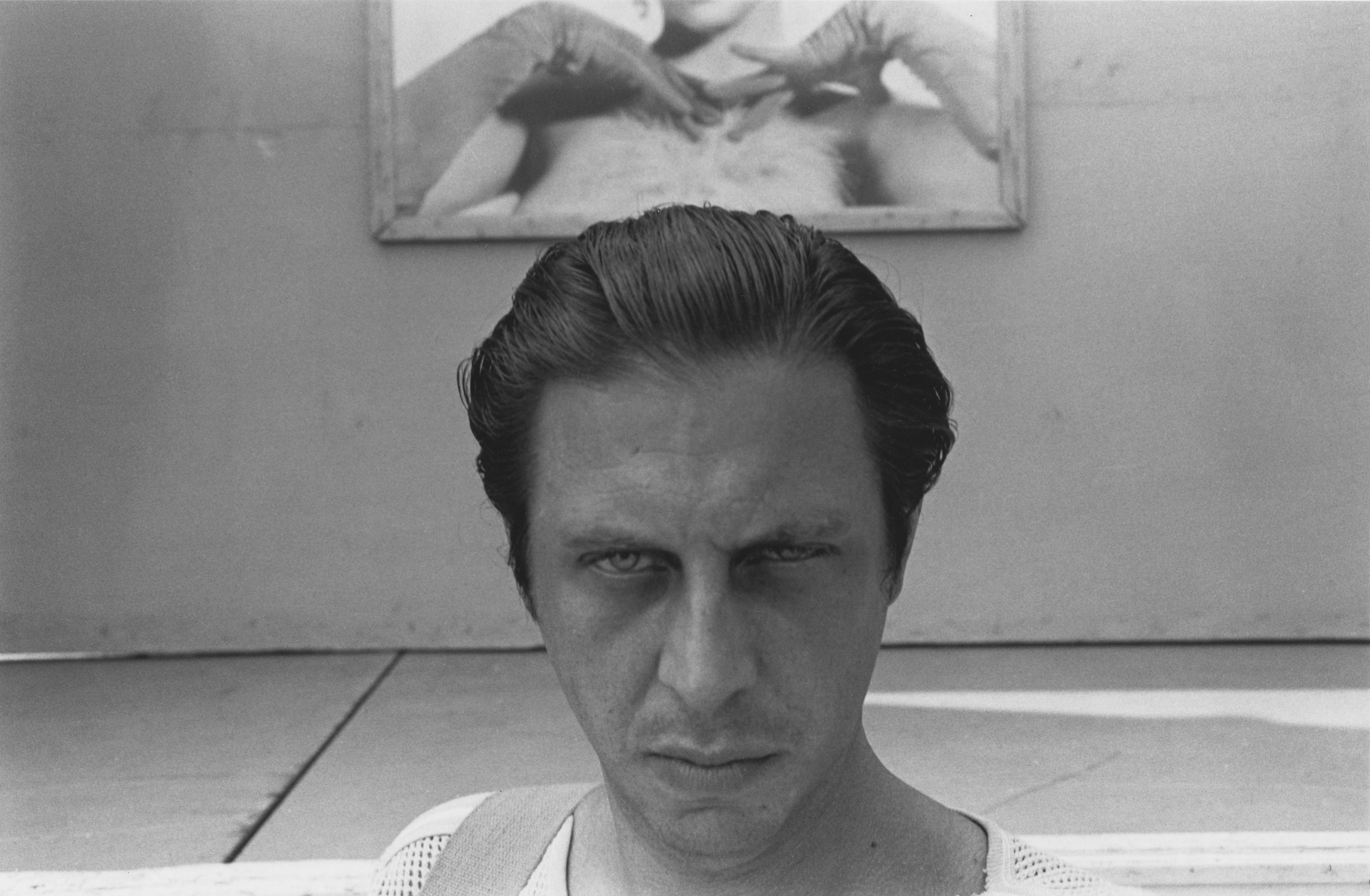

If the accepted definition of an orchestra is an ensemble of musicians playing a variety of instruments, a new exhibition at the Fondation Cartier makes the case that animals in their natural habitats are an orchestra of the purest form. Its conductor – or perhaps more accurately, its conduit – is Bernie Krause, a long-time musician, recording engineer and producer who has been collecting and archiving the sounds of creatures in the wild since 1968. As a pioneer in soundscape ecology, he is credited with the notion of a ‘biophony’ or ‘niche hypothesis’ – the collective sound produced by animals carving out their particular acoustic niche in a given environment.

EXCLUSIVE: listen to Krause’s recording from Mungwezi Ranch, Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe

With 'The Great Animal Orchestra', which also happens to be the name of his recently published book, Krause's scientific work is positioned within a more artistic (but no less relevant) construct. The exhibition gathers together a diverse group of artists (Cai Guo-Qiang, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Adriana Varejão and Agnès Varda, among others) who have created works from these soundscapes. But Krause’s recordings are the main attraction, in part because the 77-year-old’s selection of audio segments have been married to dynamic visual sequences commissioned by the Fondation Cartier and executed by London-based creative studio, United Visual Artists.

The installation can be found in the building’s darkened lower level, where his biophanies from North America, the Amazon, the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve in the Central African Republic and the oceans are optimised as an immersive experience far removed from the source material. Here, the unintended music of crows, Eastern wolves, blue jays and squirrels from Algonquin Park, Canada – as one example – appears as both a graphic of flashing red light and a streaming projection of digital information interpreted from a spectrogram. Along with a shallow reflecting pool, which translates the deepest sounds as rippling water, the combined visuals translate frequency, intensity, duration and possibly even communication in an evocative way. Without any images of animals, the effect becomes one of comparison. The clicking noises from a whale might conjure up an MRI machine; the howling wolves sound like sirens; chirping cicadas might have inspired electronic dance music. Then comes the irony that these comparisons reinforce an anthropocentric view – as humans, we’re often just mimicking the natural world.

Despite the fact that the animals are communicating freely without any direction, Krause refers to the 12-minute recordings as ‘compositions’, since they exist within a timeframe. Further, he notes how these limited critter voices have 'evolved to find their acoustic niche where there is enough bandwidth to express themselves to both transmit and receive information in a way that's going to support their existence'. The streaming spectrograms, he says, makes this clear.

When asked whether the digital depictions – both recordings and visuals – take us deeper into nature or suggest an abstracted experience, Krause’s straightforward reply is both. ‘It has its origin in the natural world. But it's obviously an illusion, because what's taken from Algonquin Park is now in Paris. And that's a bit of a stretch,’ he tells Wallpaper*.

But within the abstractions is a sobering truth: these sumptuous biophonies are changing as habitats become increasingly threatened – or, in extreme cases, no longer exist. Biodiversity is diminishing but also, as he observed from birds near his home 80km north of San Francisco, their sounds are no longer the same. This makes his recordings (currently obtained using a portable Sound Devices 722 or 744 recorder and Sennheiser MKH microphones) even more valuable, and why visiting cities can feel so enervating. ‘I hear the wild critters that live in a city struggling for purchase. And in the natural world, that's not the case,’ he explains. ‘They all have to find their niche again, whether it's a physical niche or an acoustic one.’

Krause has been collecting and archiving the sounds of creatures in the wild since 1968. As a pioneer in soundscape ecology, he is credited with the notion of a ‘biophony’ or ‘niche hypothesis’ – the collective sound produced by animals carving out their particular acoustic niche in a given environment.

The 77-year-old Krause's selection of audio segments have been married to dynamic visual sequences commissioned by the Fondation Cartier and executed by London-based creative studio, United Visual Artists.

This exhibition gathers together a diverse group of artists who have created works from and in response to Krause's soundscapes. Pictured: installation view.

The artists featured include Cai Guo-Qiang, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Adriana Varejão and Agnès Varda, among others.

INFORMATION

’The Great Animal Orchestra’ is on view until 8 January 2017. For more information, visit the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain website

Photography courtesy Lumento

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Fondation Cartier

261 Boulevard Raspail

Paris, 75014

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories

-

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friends

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friendsInspired by artist Sophie Calle, Colleen Kelsey’s ‘Wearing It Out’ sees the writer ask ten friends to tell the stories behind their most precious garments – from a wedding dress ordered on a whim to a pair of Prada Mary Janes

-

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan Bell

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan BellWhat were our chosen conveyances in 2025? These ten cars impressed, either through their look and feel, style, sophistication or all-round practicality

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Inez & Vinoodh unveil romantic new photography series in Paris

Inez & Vinoodh unveil romantic new photography series in ParisA series of portraits of couple Charles Matadin and Natalie Brumley, created using an iPhone in Marfa, Texas, goes on show in Paris

-

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list played

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list playedChinese restaurant Davé drew in A-list celebrities for three decades. What happened behind closed doors? A new book of Polaroids looks back

-

All eyes on Paris Photo 2025 – focus on our highlights

All eyes on Paris Photo 2025 – focus on our highlightsThe world's most important international photography fair brings together iconic and emerging names, galleries large and small – and there’s much to covet

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThe clocks have gone back in the UK and evenings are officially cloaked in darkness. Cue nights spent tucked away in London’s cosy corners – this week, the Wallpaper* team opted for a Latin-inspired listening bar, an underground arts space, and a brand new hotel in Shoreditch

-

Ten things to see and do at Art Basel Paris 2025

Ten things to see and do at Art Basel Paris 2025Art Basel Paris takes over the city from 24-26 October. Here are the highlights, from Elmgreen & Dragset to Barbara Kruger and Dash Snow

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, our editors have been privy to the latest restaurants, art, music, wellness treatments and car shows. Highlights include a germinating artwork and a cruise along the Pacific Coast Highway…

-

Pantone’s new public art installation is a tribute to Coldplay’s ‘Yellow’, 25 years after its release

Pantone’s new public art installation is a tribute to Coldplay’s ‘Yellow’, 25 years after its releaseThe colour company has created a – you guessed it – yellow colour swatch on some steps in Wembley Park, London, where the band will play ten shows this month