’Architectones’ by Xavier Veilhan at Richard Neutra’s VDL House, LA

After much-lauded exhibitions on the grounds of Château de Versailles in France and one would expect Xavier Veilhan to find even larger venues to host his arresting installations, but the Paris-based artist likes to surprise.

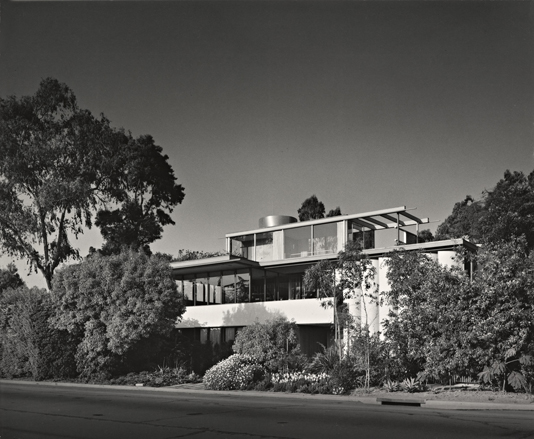

Veilhan's latest setting is much more intimate in scale. The artist has selected architect 's 190sqm VDL House in Los Angeles as the first stop for his worldwide investigation of art within the context of modernist architecture.

Named after the 'architectons' of - compositions of white ceramic blocks that extended the Suprematist philosophy into architecture - the 'Architectones' project will also see Veilhan working in modernist icons like nearby ,and in Moscow, teasing out each site's unique characteristics and responding with site-specific work.

At the VDL House, Veilhan has created monochromatic pieces that echo the home's neutral palette and sleek construction. Gone are the audaciously coloured carriages or fire engine red sculptures of Hatfield, which are instead replaced by pieces that blend into the home's metallic environment.

'I didn't want to make something that's disruptive, more something that is part of the house,' said the artist. Indeed, each piece appears around corners of the home like a full stop at the end of a sentence instead of an exclamation point. Rendered mostly in black (or in some cases, reflective metal), Veilhan's pieces echo the same sensitivity to its surroundings as the VDL House does to its Silver Lake neighbourhood.

Each installation reveals a sliver of Neutra's professional and personal life or the artist and his family's experience of the home, says Veilhan. The family has been living in the home for the past two weeks.

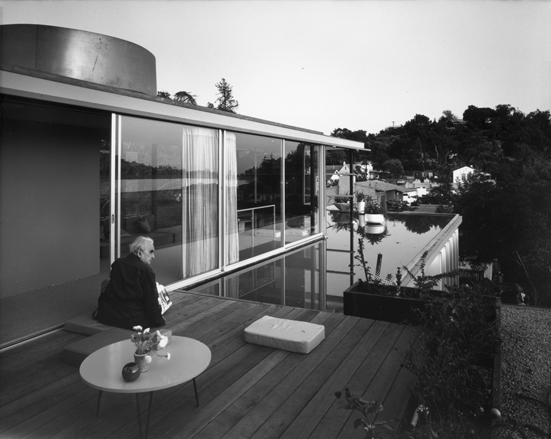

Black metal carpets cut out in the shape of the architect's native Austria and adopted California become figurative representations of Neutra's formative environments. A white gold mobile echoes the use of aluminum in the home. It hangs by the second floor's panoramic windows and quivers in response to the occasional wind, a reminder of the home's much lauded blurring of interior and exterior environments.

Some installations pay homage to the leaps in technology that informed Neutra's machine-for-living architecture. The Ford Model B with a model VDL house for an engine ties together the car and home's parallel history; both were first birthed in 1930s and then re-fashioned in the 1960s. The Model Bs became the nation's first hot rods and the VDL House was re-designed by Richard Neutra and his son, Dion, after a devastating fire.

On the top floor, a model Blue Flame, the rocket-powered vehicle that broke land speed records in 1970, holds a figure sprawled in its womb, a reference to Neutra's penchant for reclining his seat in the car to stare at California's skies.

Curated by Los Angeles-based architect Francois Perrin, 'Architectones' in VDL House showcases an artist's restrained hand. Rather than a power play for attention, Veilhan's installations act more like physical bookmarks that remind visitors to stop and ponder the then-groundbreaking dynamics of the home and the lives that unfolded within its walls.

Wallpaper* caught up to Veilhan days before his exhibition opening to find out what it's like to have such a personal encounter with this architectural icon…

Wallpaper*: How did the idea for this project begin?

Xavier Veilhan: When I was a kid, I remember seeing some modernist buildings in books. I didn't even know that an architect designed them. [The structures] were more like cars or something like that and I've always been fascinated with them.

Then, when I was in Versaille, I noticed that what I really wanted was to be able to show my work in what were ultimate venues for me. I thought maybe I should just talk about it with some people and then the whole thing [developed from there]. It was a long process, but easy.

W: Why stay in the VDL House when you could have just simply visited and walked the grounds?

V: I think that whatever you do is a way to get in touch with things you love. Part of the reason I do art is because it's an excellent way to get in touch with people that most can't get in touch with, or get access to places like these.

At a certain point, I thought, if I wanted to live in these houses, what reason could I give? Maybe I could say, I have to take photographs for a magazine or something like that but that wouldn't have allowed me to stay in the house. Maybe this whole thing is just a big plan to get access.

W: It's a very good one. How did you choose your venues for Architectones?

V: I made my choice based on the architecture I love the most, which is a very artistic choice, not an art historian or architectural historian's choice.

W: You and your family have been at the VDL house for about 25 days. What do you think of the home now that you've lived in it?

V: This house represents a later idea of modernity because the original house was built in 1932 and re-built in 1963. Still, there is a kind of control freak architecture about it. Everything is intentional and there is not much furniture that you can move around - most of it is built-in.

But to live in it, you understand more about the feeling that the architect wanted to provide. There's no trick in it because the architect made this house for himself. It's like a cook that cooks his own meal.

W: What does your family think of the VDL House?

V: They love it. They love it in a way that's not like 'ooh ahh, look at that' but just about using it. A house is not really like an object. If you have a plate and you put it in a museum, you won't have the use of it, but it will work in a way, you can still look at a plate. A house has to have something happening in it.

W: We know it's like picking children, but which installation would you say is your favourite?

V: No, no, no, I'm very good at picking children. (laughs). No, I'm actually quite curious right now because I'm discovering half of the work [as we install each piece]. So far, I like the mobile because we've been living with it for a week now. It always keeps the same form but changes in a way. It's like a random program. Each time that you open the window, something happens. People behave towards it differently and also seeing how it changes every time I arrive at the house. The white gold reflects the silver feeling about the house that I like. It also reflects the golden light right before evening.

W: After going through the process once with the VDL House, what things would you do and not do again?

V: I don't know if I can say. I'm always start with a big list of things that I want to do, then reducing it until I get to the corn. I'm in the same process for the [Pierre Koenig's] Case Study House # 21 that I'm working on. Every venue is leads to different context and result. At the Cité Radieuse rooftop, we'll have a performance there by an eighty-something year-old experimental electronic musician.

W: What do you hope people take away from the show?

V: Each time, I do site specific things, I hope that the art is not something you look at but you look through so that it's a tool to notice something about the environment.

Sometimes, art is only a way to point people to things that are existing but that you don't see, like the movement of the air from the mobile. Maybe art can be something that just focuses people on some elements like the light here or the movement of the air, or the this kind of exterior-interior relationship, which is important in this house. I hope [my work] will just help point that out.

Neutra's house played host to Veilhan and his family for a two week period, while the artist was creating his site-specific 'Architectones' installations. These are now being exhibited in the building as part of a public show that runs until 16 September

The VDL house was originally built in the 1930s for Neutra's office and his family but it burnt down in 1963. It was then rebuilt by Neutra (pictured) and his son Dion. They built two floors and a penthouse solarium on the original prefabricated basement, applying what they had learned in the interim about sun louvers, water roofs and physiologically motivated design

'Neutra on Horseback', by Veilhan, echoes the architect's penchant for riding his horse in the nude. 'This image of such a venerable architect naked and at one with nature really resonated with me,' says Veilhan. 'After hearing his story, I decided to pose nude. I then carved a horse and its rider out of Styrofoam. The surface of the work is sculpted with carved stripes reminiscent of wooden sculptures'

A large black flag sculpture sits atop the house. As well as evoking the historical setting, according to the artist, 'it is a sign of this special private building opening out to the public'. During the opening evening of the exhibition, the artist also staged an 'airplane performance', for which a plane flew over Silverlake Reservoir pulling a black banner as an blank, abstract announcement of the exhibition's opening

Veilhan's 'Adult man (Richard Neutra)' acts like a street sign for the show and echoes others you might find on the streets of LA

On the top floor, a model Blue Flame, the rocket-powered vehicle that broke land speed records in 1970, holds a figure sprawled in its womb, a reference to Neutra's penchant for reclining his seat in the car to stare at California's skies

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.