Crossrail shifts seven million tonnes of earth to make London more connected

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

London’s Farringdon Station is about to break into the infrastructural big time, becoming a key interchange on the world’s oldest and most prestigious transport network. With the coming of the Crossrail project and its Elizabeth line, this historic stop on the edge of the City of London will be a meeting point for Tube and rail. Carving out thousands of cubic metres of earth beneath a 2,000-year-old city was always going to be a challenge, yet as you walk along the deep-level platforms, crossovers and tunnels of this shiny new piece of the capital’s transport jigsaw, it seems almost impossible to conceive that everything around you is totally new.

For over three years, the city’s ancient soil was gouged out by eight massive tunnel-boring machines, excavating an estimated seven million tonnes of material. Once the tunnelling was finished, two of the 1,000-tonne boring machines were simply embedded in the walls of the station, rather than haul them up from a depth of 40m. The new tunnels and platforms were then lined with 200,000 concrete segments, before being given a polished finish to join the dots with London’s transport design aesthetic.

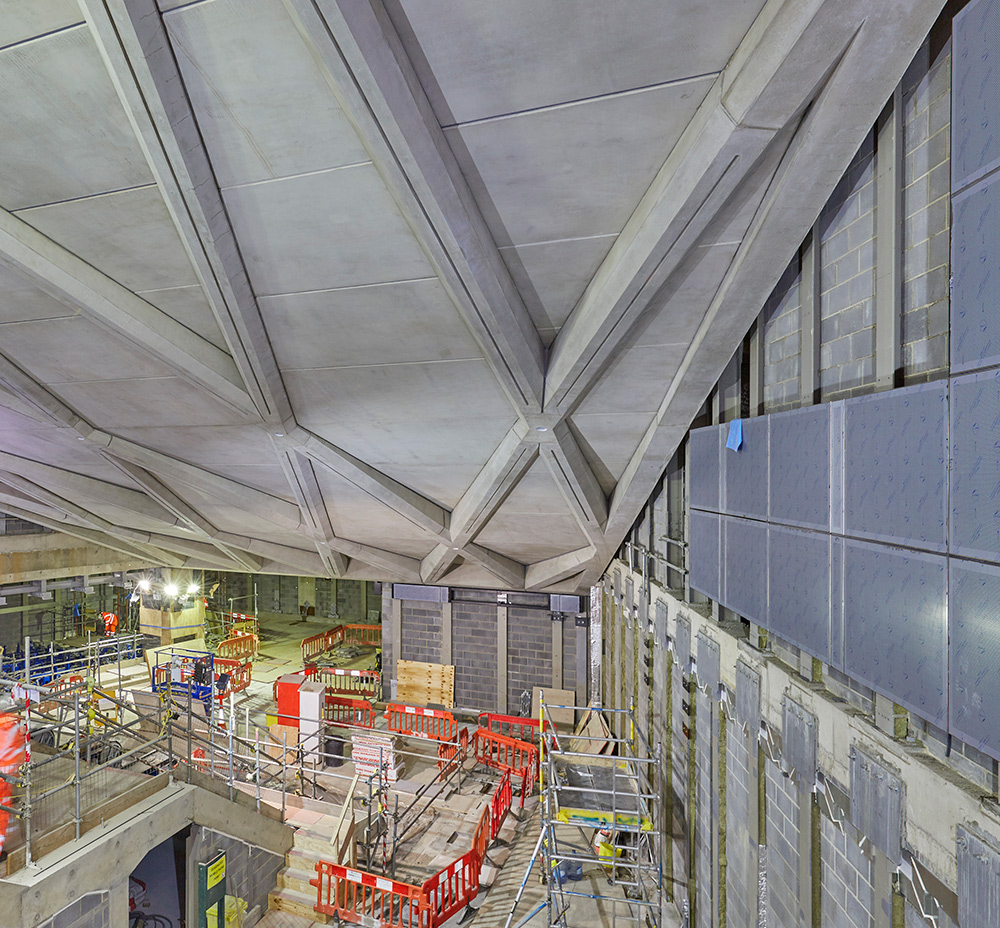

The faceted concrete ceiling of Farringdon’s new western ticket hall, which will link up with the Thameslink platforms. The diamond-shaped forms are a nod to the nearby Hatton Garden jewellery quarter.

Farringdon is nearing completion. The first stage of the Elizabeth line will officially open in December 2018, with the entire route expected to be up and running a year later. For now, the plastic wrap is staying on the shiny new lighting upstands and station indicators, while platforms are cluttered with escalator parts and boxes of tiles. In June, the track will go live for train testing.

The Crossrail project probably exceeds even the ambition of London’s original 19th-century Tube lines. The final cost will be around £14.8bn, with about a decade spent on construction. All this money has been poured into a system that’s not just about increasing capacity, but broadening the perceived boundaries of London, how far it extends, and how locals and visitors engage with such a sprawling city. Trains and transit inspire streams of statistics and facts, but London is not easy to catalogue. Its rail network expands in fits and starts, its tentacles reaching out into some suburbs while leaving others isolated. It is a city of interchanges, crossovers and links, with around 366 railway stations and 270 Tube stations (some of the former include the latter). Ever since the system was given a cartographic nip and tuck by Henry Beck’s Tube map in 1933, the form of the network has stayed familiar. But Beck’s graphical simplicity cleverly conceals the geographical reality. Our mental map of London is skewed as a result.

The Elizabeth line will see another colour added to the map, punching a purple swathe through the tangle to make a host of new connections. Forty one stations, ten of them newly built, are strung along it, while spurs reach down to the Heathrow terminals and Abbey Wood via Canary Wharf. Eventually, the whole line will take you from Reading in the west to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east. That’s around 57 miles as the crow flies, 26 of which run through the new tunnels blasted beneath London.

Some of the 81 new escalators being installed on the Elizabeth line.

Enough of the statistics. The sense of the greater good is strong with public transport projects, and for all its faults, the capital’s network is still seen as one of the best in the world and a source of civic pride. The upheaval brought by Crossrail has proved challenging, with stations and roads closed, routes re-routed, timetables changed and chunks of streetscape demolished, most notably at Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road and Farringdon. But now the last is set to become one of London’s most significant stations, thanks to the intersection of the Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Tube lines with a National Rail station serving both City Thameslink and the Elizabeth line. This is the kind of option overload that city planners usually only get to dream about. With rapid connections to Heathrow and Gatwick and around 140 trains an hour at peak times, Farringdon is on track to becoming an urban crossroads that links north and south, east and west, the UK and the rest of the world.

The new station descends eight storeys below street level, with banks of escalators and new inclined lifts set beneath the faceted concrete roofs of its two ticket halls. The back of house is already a forest of pipes and conduits, with vast vent shafts adjoining slender access ways and complex weaves of wiring. Crossrail will eventually serve up to 200 million passengers a year, but none will see behind the scenes. Instead, they’ll be treated to the purple-tinged branding that ties the Elizabeth line into the network, the crisply detailed concrete panels, the discreet lighting and elegant signage, as well as a significant chunk of new art (see below).

Most of all, Londoners will have their horizons vastly expanded; by descending these escalators they’ll be within a few hours of practically anywhere on the planet.

Art underground

From a digital piece by Israeli photographer Michal Rovner at Canary Wharf to British artist Simon Periton’s gems cascading down the Farringdon concourse, Crossrail will deliver site-specific works across seven stations.

Yayoi Kusama, Liverpool Street

Kusama’s Infinite Accumulation, with mirrored steel spheres connected by tubular rods, gives sculptural form to her renowned polka-dot motif. Photography: © Yayoi Kusama, courtesy Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro

Spencer Finch, Paddington

American artist Finch’s A Cloud Index sees his pastel drawings digitally transferred to a 120m x 18m glass canopy above Paddington’s ticket hall. Artwork: © Spencer Finch, courtesy Lisson Gallery

Chantal Joffe, Whitechapel

British painter Joffe spent a Sunday afternoon observing the community in Whitechapel to create a playful portrait series that will adorn the platforms. Artworks: © Spencer Finch, courtesy Lisson Gallery

As originally featured in the June 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*231)

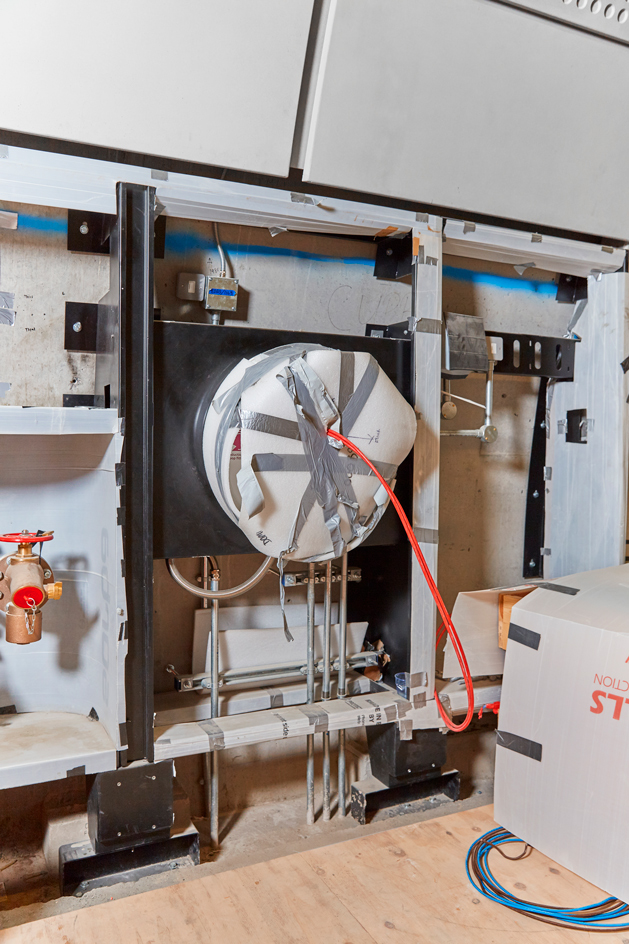

A help point is swathed in plastic amid work in progress at the new Farringdon Station

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the TFL website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.