Architecture news: Letter from Australia

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

National Museum Café, Canberra, by Ashton Raggatt McDougall

Iconic cars, planes, tractors and tanks take up a lot of gallery space, and Canberra's National Museum, built in 2001, had run out of places to park them. An increasing number of its rare vehicles were being mothballed and left in storage, instead of finding a home in the Ashton Raggatt McDougall-designed space. Former National Museum of Australia director Andrew Sayers started to eye the large entry hall, which was being used as a café. Original architects Ashton Raggatt McDougall were re-engaged to add an annexe for the café and restaurant spaces, freeing up exhibition space and unfying the Cuiseum café and Axis restaurant areas. The $3-million, 200-seat café is shaped like a toy puzzle, continuing architect Howard Raggat's original theme of the gallery as a puzzle that fits together the disparate cultures that form the Australian nation. Floor-to-ceiling windows provide diners with stunning views of Lake Burley Griffin, while in the entry hall, rarities such as British-made single-engined Percival Gull monoplane have been wheeled into place.

GASP 2, Glenorchy, by Room 11 Architects

GASP 2, Glenorchy, by Room 11 Architects

Once quaint Hobart has been recast as a small but modern city in the past two years. GASP 2 (Glenorchy Art & Sculpture Park Stage 2) responds both to the surrounding waterside landscape and a newfound sophistication in the city - sparked by the creation of MONA, a privately owned, A$80 million museum that has attracted art-savvy tourism. Local firm Room 11 Architects, lead by chief architect Thomas Bailey, created GASP 2. A concrete pavilion, it serves as both a ferry terminal servicing MONA and a stop-off point for those who prefer to cycle to the gallery along GASP 1 - a 4k-long wooden boardwalk and pathway. MONA, situated just outside of Hobart, has attracted over 400,000 visitors in its first year alone - drawn to the private collection of antiquities and contemporary art amassed by local boy turned billionaire professional gambler David Walsh. GASP! 2 is situated in Walsh's boyhood suburb of Glenorchy, a once struggling suburb that has welcomed the influx of tourism money and the nine-hectare sculpture park, ferry terminal and pavilion. Photography: Ben Hosking

Luna, Melbourne, by Elenberg Fraser

Luna, Melbourne, by Elenberg Fraser

If you're tired of designers describing their buildings in arch-industry speak this might be the apartment for you. It's based on Princess Leia's 'dancing girl' gold bikini. Yes, that's right, the intellectual underpinning of Luna's curvy, shimmering gold façade is Carrie Fisher's iconic outfit in Return of the Jedi. Add the fact that it stands 700m from St Kilda beach and the gold bikini metaphor makes even more sense. But local firm Elenberg Fraser's $16.2 million, four-storey residential project Luna is not just a shiny thing that catches the eye; the narrow sliver of land on which it was constructed demanded a clever use of space and attention to privacy. The resulting shape is reminiscent of New York's Fifth Avenue Flatiron building. To keep things private, shutters fitted with outside lights wrap around the building. More privacy is provided by the building's skin. Its woven anodised aluminium mesh is shaped in a way that allows residents to see out, but blocks the view in. Gold tinted glass works to not only reflect unwanted views but also mediates against the harsh summer sun.

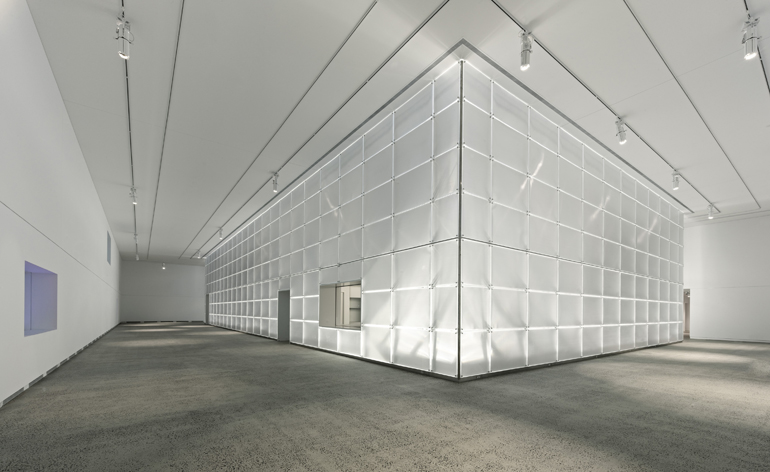

National Centre for Synchrotron Science, Melbourne, by Bates Smart

National Centre for Synchrotron Science, Melbourne, by Bates Smart

Australia's second-oldest architecture firm has created one of Australia's most futuristic public buildings - a glowing cube that sheds new light on the subject of light. Englishman and former Herzog de Meuron architect Kristen Whittle has concieved a building that celebrates the research done at this centre - which is to accelerate charged electrons until they create a beam that nearly hits the speed of light, then research ways to use such light. Simple. The polycarbonate-wrapped two-storey building measures 50m x 50m and sits at the edge of Monash University Campus. Like a modernist Ularu, the building changes colour during the day as the sun hits its interlocking dichroic panels. Inside, natural light is directed down translucent, acrylic wall panels, minimising electricity use.

At the centre of the building sits a 400-seat auditorium encircled by an exhibition and event space - referencing the circular synchrotron that stands only a few dozen metres away. Signage and graphics are by one of Australia's most revered graphic designers, Garry Emery. Photography: Peter Bennetts

Infinity Centre, Penleigh and Essendon Grammar School, Melbourne, by McBride Charles Ryan

Infinity Centre, Penleigh and Essendon Grammar School, Melbourne, by McBride Charles Ryan

McBride Charles Ryan's Infinity Centre for Penleigh and Essendon Grammar School in Mebourne was inspired by the infinity symbol that forms part of the school's combined girls and boys school logos. The school allows a flexible approach to learning within set parameters - an ethos that the architectural team, headed by MCR principal Robert McBride, embodied in the structured yet fluid design. The figure-of-eight plan on an 'L'-shaped site contains two courtyards, both sheltered from sometimes severe winds. The shape is finished in a skin of glazed black and grey tiles that echo the black brickwork of a junior school building that MCR completed in 2011. Photography: John Gollings

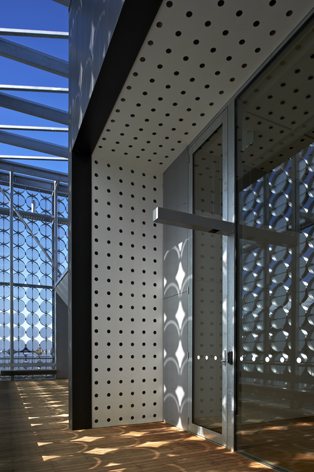

RMIT Design Hub, Melbourne, by Sean Godsell

RMIT Design Hub, Melbourne, by Sean Godsell

Sean Godsell's A$62 million RMIT Design Hub is a place that both attracts and promotes current and future design talents, ranging across architecture, fashion, industrial design, landscape and urban design. And it will surely prove an economic boon for the city. The 16,000 sand-blasted discs that form the skin of this 12,000sqm building create a visual metaphor for all that is good about design in Melbourne. But the glass discs are not just about aesthetics. Computer-controlled, they track the sun's position, pivoting to heat or cool the building, and when solar technologies catch up with this design, they will be able to be incorporated into the skin. One day, a solar-powered, sun-tracking RMIT Design Hub may be carbon neutral. Standing at the top end of Melbourne's key shopping and academic street corner of Victoria Street and Swanston Street, the design research centre, designed in association with Peddle Thorp Architects, welcomes the public in. The western forecourt contains the (admittedly well hidden) Design Hub Café, and inside exhibition space Design Hub Gallery has regular exhibitions of work created onsite. Photography: Earl Carter

M2, Adelaide, by John Wardle Architects and Swanbury Penglase

M2, Adelaide, by John Wardle Architects and Swanbury Penglase

The University of South Australia's Mawson Lakes campus found itself in an unusual position - literally. When the campus was built 12km north of the city of Adelaide in the 1970s, it was sited near an abattoir yard, so it positioned its entrance as far from the yard as possible. When the slaughterhouse was shut down, a new suburb was built on the land - and the campus was left facing the wrong way. The four-storey concrete and timber M2 building by John Wardle Architects (JWA) and Swanbury Penglase shifts the focus of the university 180 degrees. M2 stands for minerals and materials, and the geology school now faces the suburb of Mawson Lakes, which takes its name from Yorkshire-born geologist and Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson. Its faceted façade references the stratification of the surrounding land - notably a stone-slab-filled dry creek. 'UniSA had a clear vision that this building would be a portal into the campus… a place where people come together to speak about science and to learn about science not just to do experiments in the lab,' JWA project architect Meaghan Dwyer said. The water and gas pipes, wiring and extractor fans are all on display behind a glass wall, and it's lit up at night. Photography: Peter Clarke

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Perth Arena by ARM Architecture with Cameron Chisholm & Nicol

Perth Arena by ARM Architecture with Cameron Chisholm & Nicol

The visually striking Perth Arena, by ARM Architecture in collaboration with Cameron Chisholm & Nicol, has won the affection of Perth residents since opening in late 2012 and has quickly established itself as an iconic city landmark. Its geometric forms are based on the 209 irregular shaped pieces of politician and inventor Christopher Monckton's Eternity Puzzle while its hue is pure Yves Klein - a bold expression that has already seen it scoop Western Australia's highest architecture prize, the George Temple Poole Award. The A$548-million, 15,500-seat multi-purpose venue is public architecture that works. Functional (including a roof that can retract in just seven minutes), eco-friendly (including the state's largest array of solar panels) and fun it is symbolic of a city that's not afraid to do its own thing.

Translational Research Institute, Brisbane, by BVN Donovan Hill

Translational Research Institute, Brisbane, by BVN Donovan Hill

Brisbane's Translational Research Institute (TRI) and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Insititute (SAMRHI) in Adelaide are manifestations of a new type of collaborative, highly functional medical research facility aimed at solving complex medical problems and attracting the very best medical researchers from across the globe. Both employ every means to attract the very best researchers to their labs - including the creation of visually unforgettable buildings. Set on a hill, the eight-story, 40-metre-tall TRI, tied to Princess Alexandra Hospital, with its façade of copper-hued glass is unmissable. The concrete, glass and clay brick structure is the work of BVN Donovan Hill, a merger of the Melbourne practice BVN (Bligh Voller Nield) with the Brisbane studio Donovan Hill. The collaborative research space brings together 650 researchers, 300 ancillary staff and 300 students in labs that owe much of their design to Wilson Architects, a practice with expertise in laboratory buildings that has contributed to the functional success of projects such as the recent UNSW Lowy Cancer Research Center in Sydney and M2 in Adelaide.

Adelaide Oval redevelopment by Cox Architecture with Hames Sharley and Walter Brooke

Adelaide Oval redevelopment by Cox Architecture with Hames Sharley and Walter Brooke

Adelaide is known around the world for three things - its impressive food and wine, its churches and the Adelaide Oval - arguably the world's most beautiful cricket ground and the site of some of the most memorable Ashes tests. Sadly, Adelaide had, for many decades, also been home to an anti-progress mindset. Ideas for regenerating the city used to go from thinktank to panel discussion to working party to the long grass - and never be seen again. It had long been recognised that the redevelopment of the ground would allow for Australian Rules Football to be played in the city. Aussie Rules football crowds were too big for the old Adelaide Oval stands. But redevelopment meant the destruction of a heritage grandstand (designed by John Morphett) so it required a sympathetic approach. The timing and the proposal were perfect. The mood in the capital shifted to one of change and modernisation just as the well-thought-out proposal was finalised. The new ground increases seating capacity, taking it from 32,000 to 50,000 while retaining the heritage scoreboard, the iconic Moreton Bay fig trees and the grassed section. The resulting $535 million redevelopment of the oval by Cox Architecture in partnership with Hames Sharley and Walter Brooke, is about more than providing new stands. The new oval will reinvigorate the city with more sporting events, bigger crowds and easier access to the ground thanks to the addition of a new footbridge across a nearby river that separates the ground from the city. The ground is being adapted to meet FIFA requirements and work as a concert venue and the new Adelaide Oval will play a key role in the invigoration of the city.

The Braggs, Adelaide, by BVN Donovan Hill

The Braggs, Adelaide, by BVN Donovan Hill

Established in 1874, Adelaide University is associated with over 100 Rhodes scholars and five Nobel laureates, one of whom, Sir Lawrence Bragg, remains the youngest scientist ever to win the Nobel Prize, at 25. Sir Lawrence and his Nobel Prize-winning father Sir William Henry Bragg are celebrated in the naming of the campus's newest building, The Braggs. Echoing the red-brick environment of the buildings on this grand old campus, the solid panels of the A$100-million building are a burnt red hue. Designed by architects BVN Donovan Hill and Hames Sharley, the 10,000 sqm, seven-storey building houses the university's world-leading Institute for Photonics and Advanced Sensing as well as a 420-seat lecture theatre and laboratories. Cleverly, the building's glass facade has been created so that it refracts and reflects the sun's rays in different ways on each floor - photonics at work.

Advanced Engineering Building, Brisbane, by Richard Kirk Architect and Hassell

Advanced Engineering Building, Brisbane, by Richard Kirk Architect and Hassell

The University of Queensland's brand new state-of-the-art building for Advanced Engineering was designed as a joint venture between Richard Kirk Architects and Hassell - the firm also behind the proposed Flinders Station in Melbourne, together with Herzog and de Meuron. The multipurpose building will host flexible education and learning spaces, as well as social areas. The structure combines teaching facilities with research laboratories, including hydraulic, wind, materials and structural, and advanced form-processing labs. 'The building also incorporates both passive and integrated sustainability initiatives with a targeted reduced energy consumption', explain the architects. Photography: Peter Bennetts