Jaeger-LeCoultre brings technical precision to guilloché dials

Humans have the upper hand at Jaeger-LeCoultre, where artisans control historic machines to give precision detailing its edge

Benoit Jeannet - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Decorative horology techniques can sometimes come across as a luxury add-on, a veneer of value to an otherwise ordinary watch dial. But the truth is, manual methods can produce results that programmed machines just can’t match. Guilloché – a very precise form of patterning – is one such art. This is why watchmakers such as Jaeger-LeCoultre, in Switzerland’s Vallée de Joux, are so careful to nurture experts whose particular feel for centuries-old crafts can make all the difference.

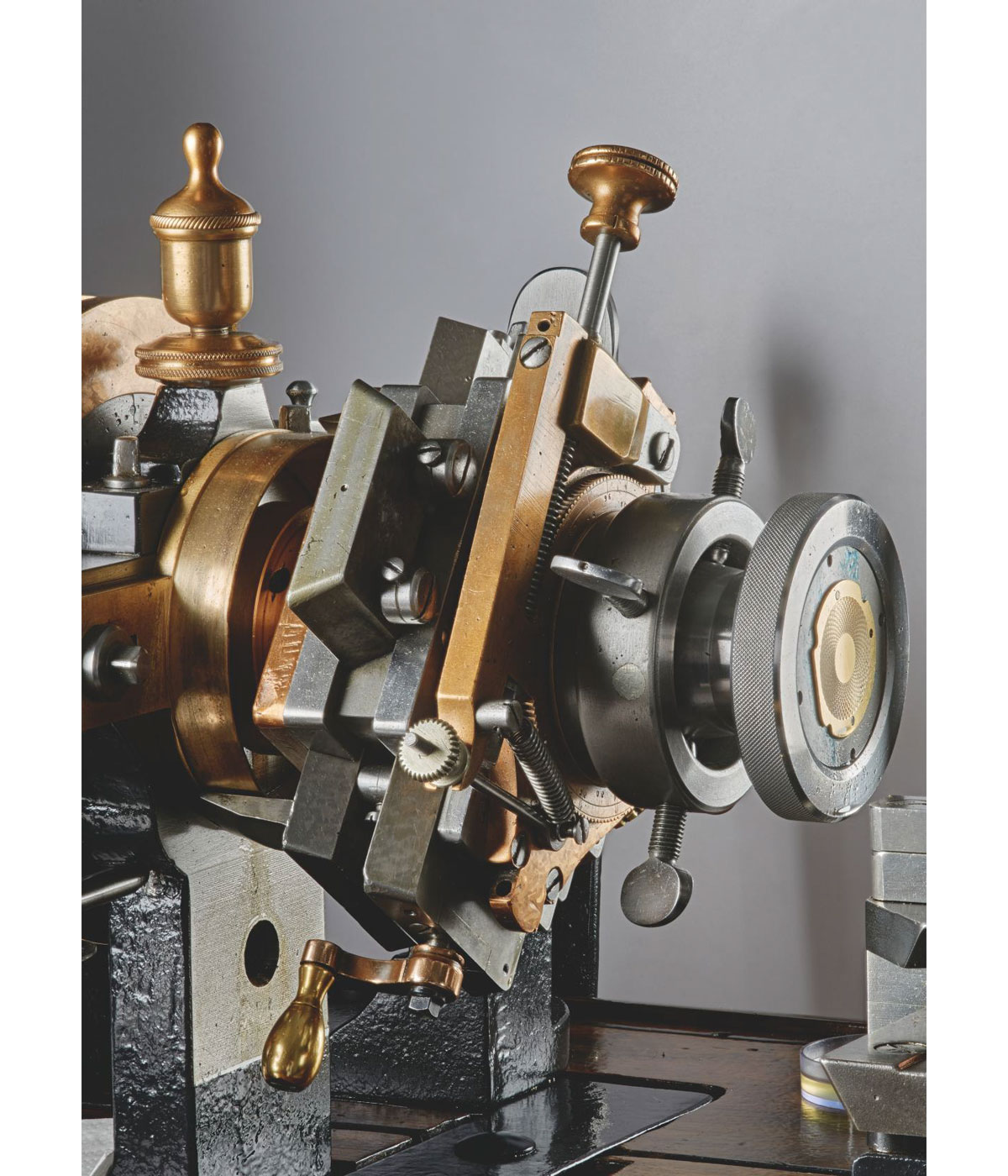

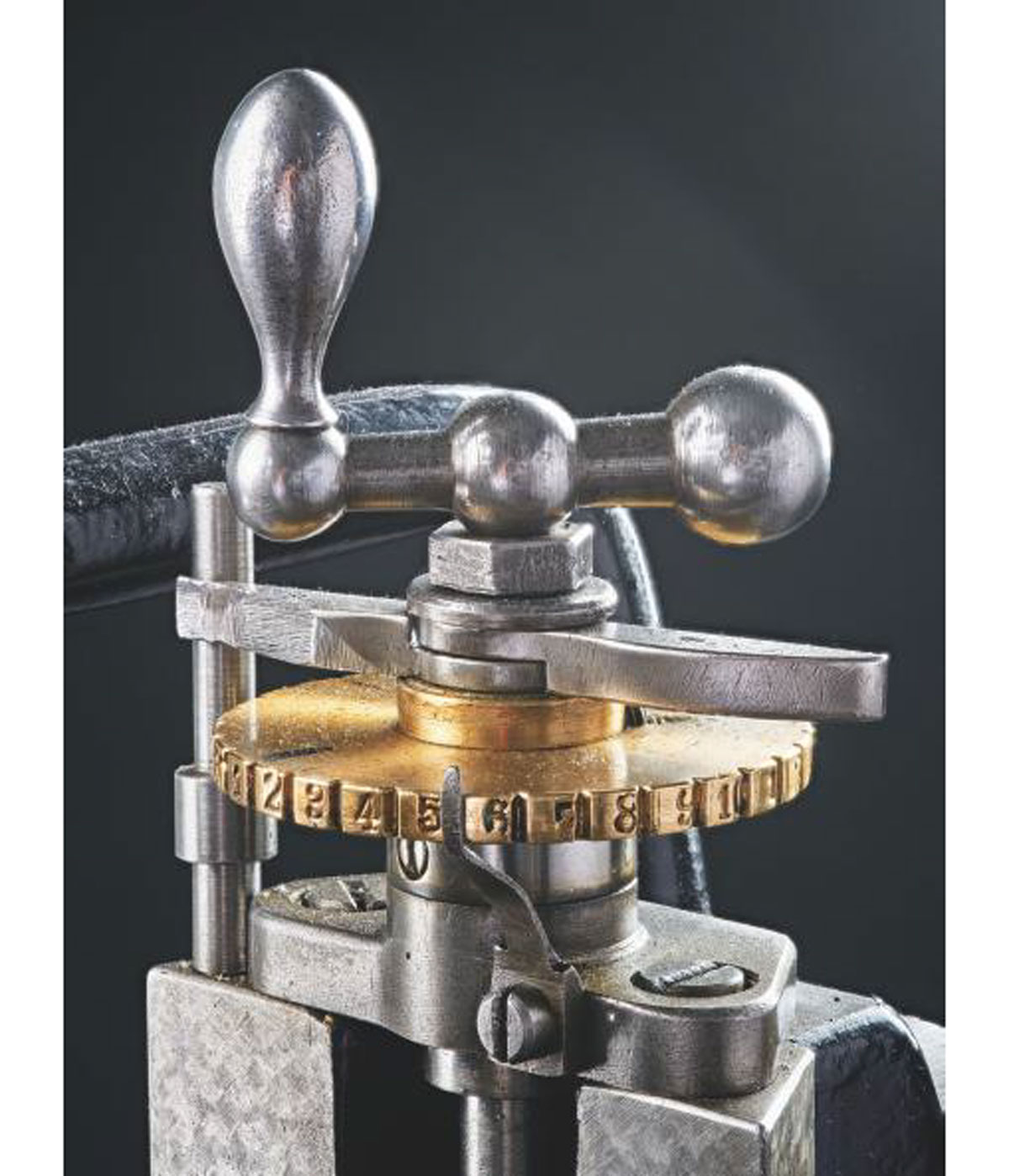

At the company’s Rare Crafts Atelier, in its HQ village of Le Sentier, up to 30 experts are collaborating at any time on a range of craft techniques, including enamelling, engraving, gem-setting and guilloché work. This last technique uses heavy, engine-turning lathes, set up to cut repetitive patterns. The skill comes in the maintenance of a perfectly regular cut, which depends on the operator having an acute feel for the material under the cutter; the regularity is achieved by making constant, almost imperceptible adjustments of pressure as the tool bites. The size and weight of the machines ensures absolute stability, and because each plate or dial has minute, unpredictable variations, the process relies on experience gleaned over years at the job. It takes almost unreal levels of concentration.

Complete accuracy is everything in cutting this dial’s sunray pattern, with the blade controlled by a ‘ligne droite’ guillochage machine from the 1920s to achieve a perfectly uniform depth for each groove

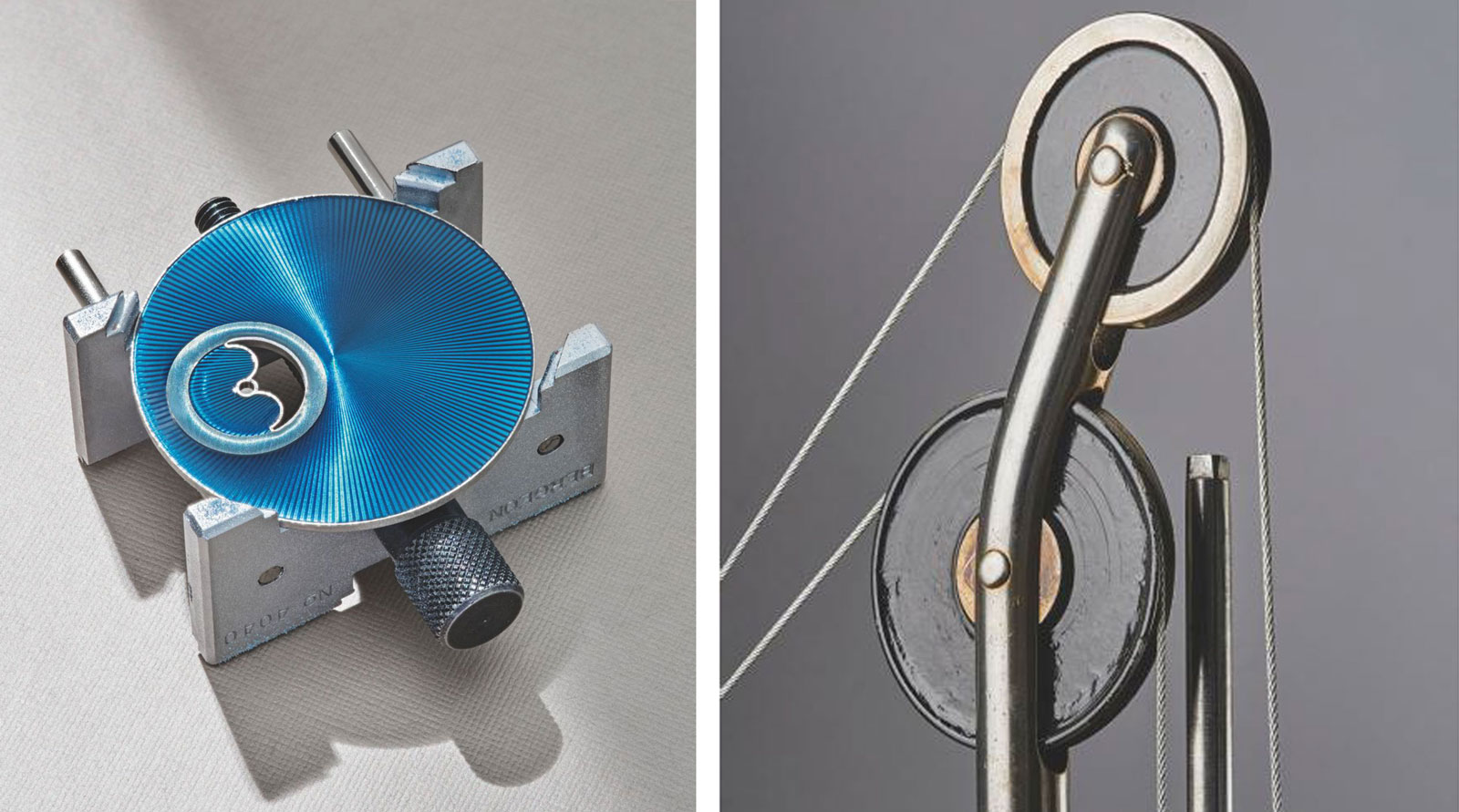

Guilloché relies on tools that have been refined over time to cut with total control and precision. They can be adjusted to the finest tolerances and react to the slightest change in force from the operator. The required combination of steadiness and sensitivity can take years to truly master

However, Murielle Romand, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s in-house – and sole – guillocheur, is nonplussed by the respect accorded to her work. ‘I find it relaxing,’she says. Romand joined Jaeger-LeCoultre in 1997 and, having previously studied micromechanics, took the decision to focus on the guilloché technique five years ago. Today she also trains an apprentice. Fine watchmakers such as Jaeger-LeCoultre are working hard to attract young people to rare artisan ateliers, lest skills such as Romand’s disappear with time.

She works between two traditional, restored machines, one of which is set up for circular cutting and the other for linear patterns. The designs emerge from a collaborative process between the watch designers, technicians and fellow craftspeople: guilloché is often overlaid with enamel, for instance, another time-consuming technique that requires master precision from all involved.

Nevertheless, Romand has responsibility for the precise size and pattern and is the ultimate designer of any guilloché pieces the house produces. The special edition ‘Hybris Artistica Ivy’ watch, for which she applied the guilloché to the dial’s micro-miniature leaves, highlights not only the level of her skill but how far the watch house will go to make use of its talent.

‘What craftspeople like Murielle achieve in a material is all about personal feel,’ says Stéphane Belmont, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s director of heritage and rare pieces. ‘We can’t get that with [an automated] machine.’ And he should know. Belmont admits that, some time ago, the house tried to automate the guilloché process for a watch design in an attempt to control enamel over-owing the dial during ring.

‘Using a machine, we could control the enamels onto the edge, but the decorative effect was flat – the surface of the dial was not shiny enough, the impressions were not good, and the light effect was poor. We noticed that the older [manually controlled] machines were better, and so we did trials and saw very different results.’ So, while the focus returned back to the craft machines, the watchmaker focused on developing a laser-cutting solution to trim the excess enamel where needed (the tolerances required to ensure water-resistance being fractions of a millimetre).

When Romand is at the wheel, Belmont says, the result is consistent: ‘Murielle’s technique means the result is the same every time – she cuts the same line three times, the pressure and speed is her own. The results are unique.’

There’s also a life in the finished dials that reflects Romand’s passion, ‘I’m happy to work on beautiful, fascinating machines. I’m proud to be the only one.'

INFORMATION

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Wallpaper* (W*257)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.