Brian Eno on his Turntable II, circular and ‘sexier somehow’

Brian Eno’s Turntable II illuminated record player gives his signature transforming lightscapes a voluptuous new form. Read more in our exclusive interview extracts

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The first Brian Eno Turntable was widely acclaimed, a collaboration with Paul Stolper Gallery that won Best Domestic Design in the 2023 Wallpaper* Awards. Part of a series of ambient, environment-altering artworks, the multi-hued turntable was also scaled up and deployed as the stage at U2’s massively complex Las Vegas Sphere residency.

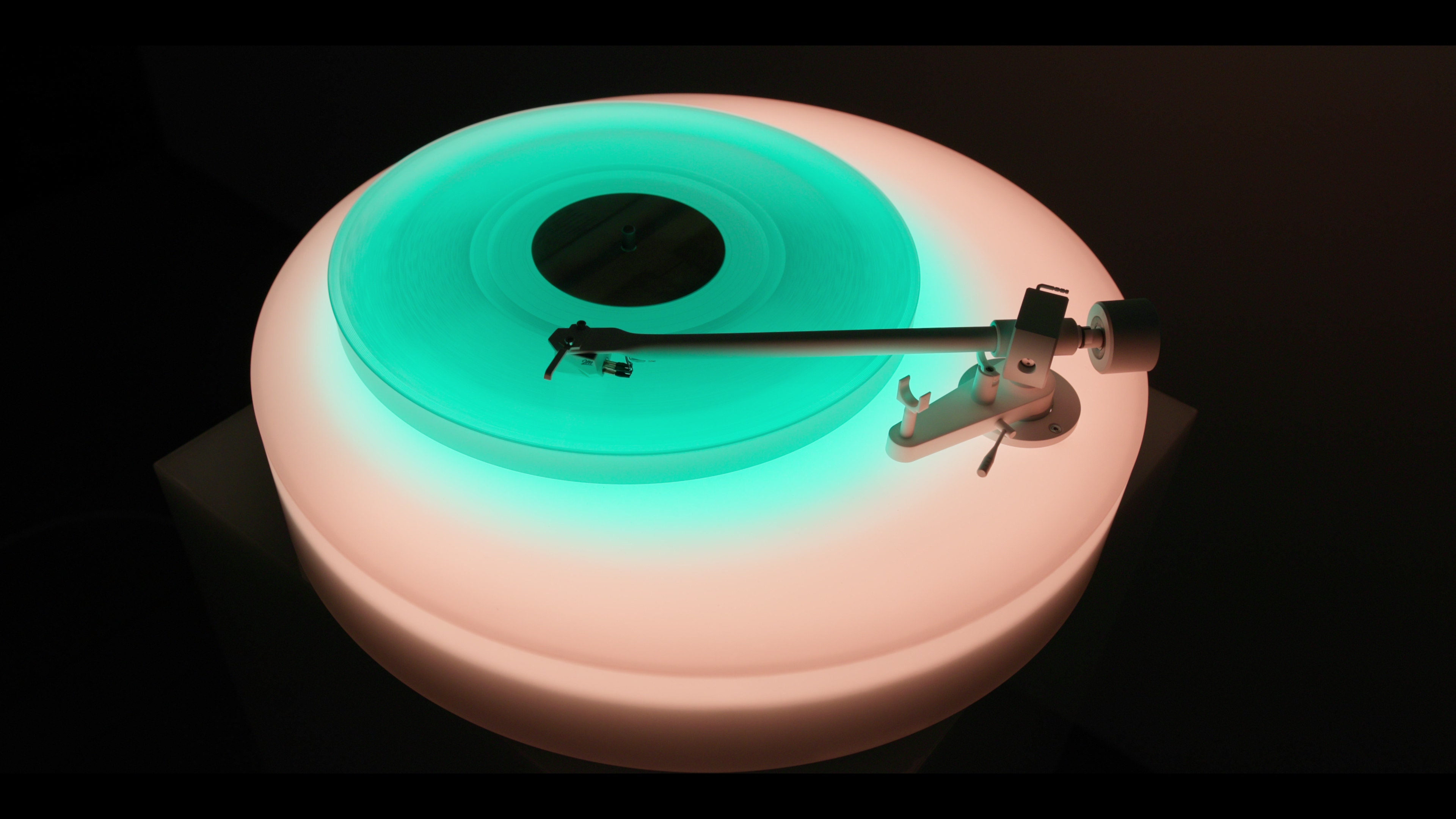

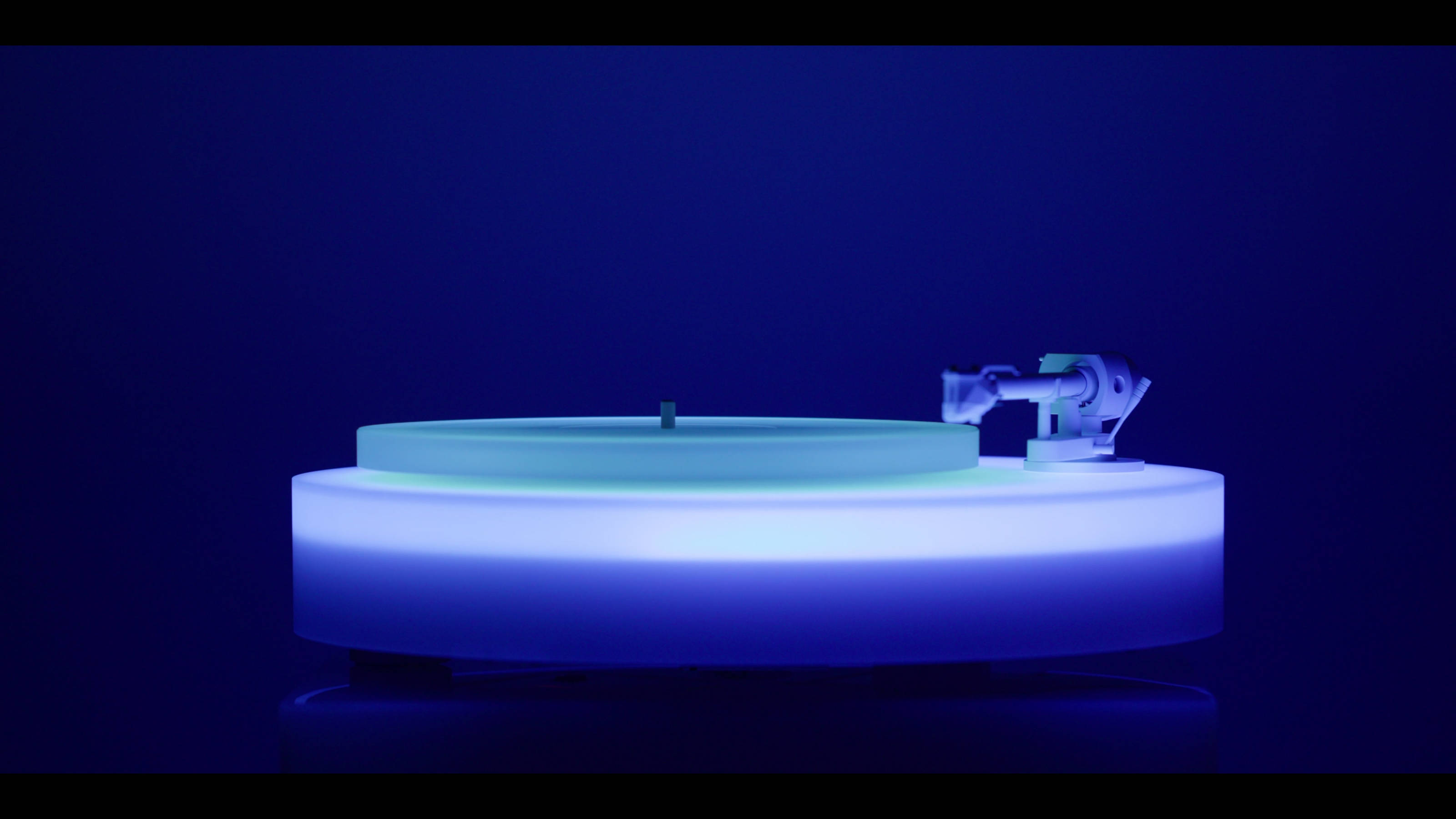

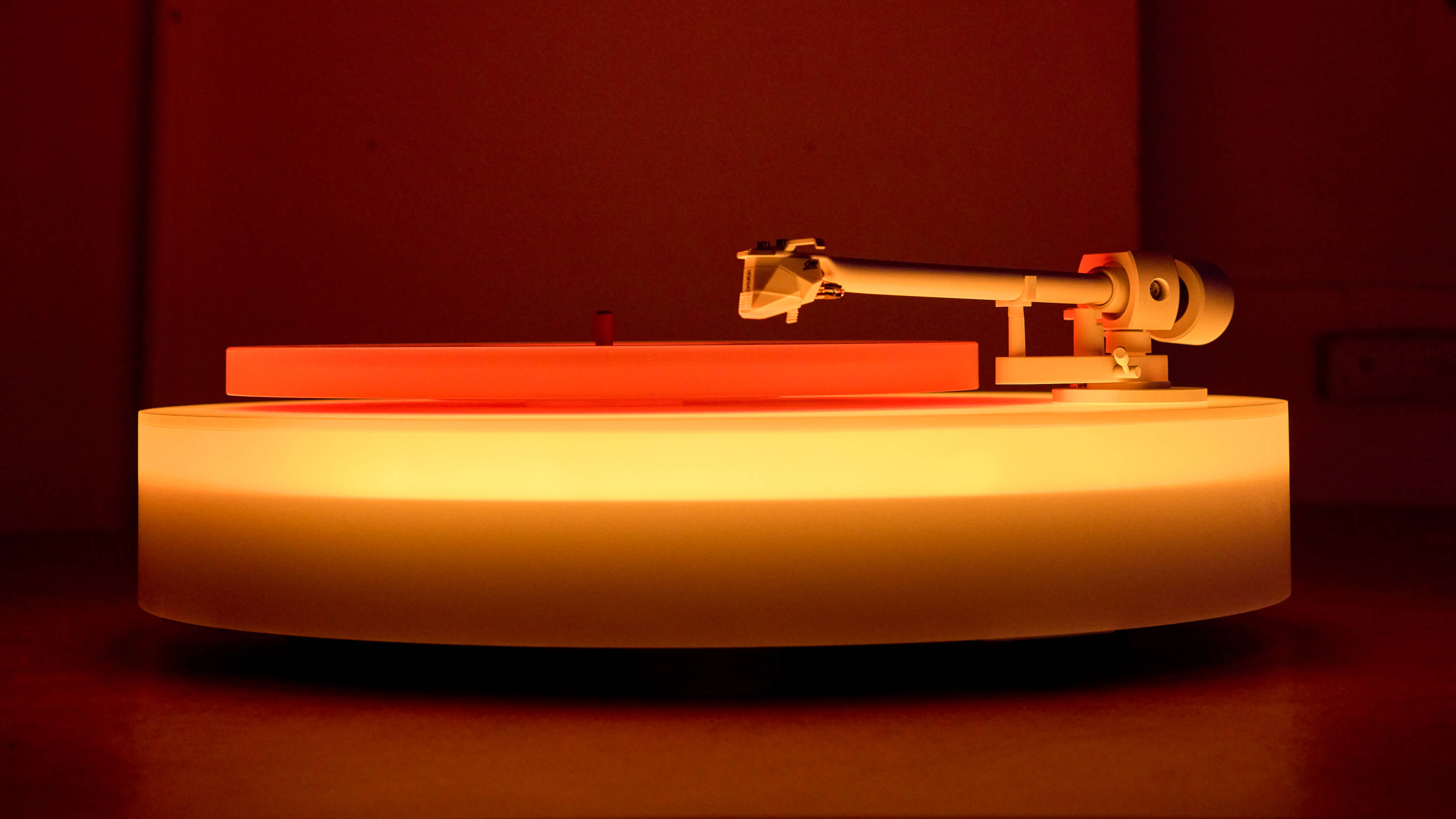

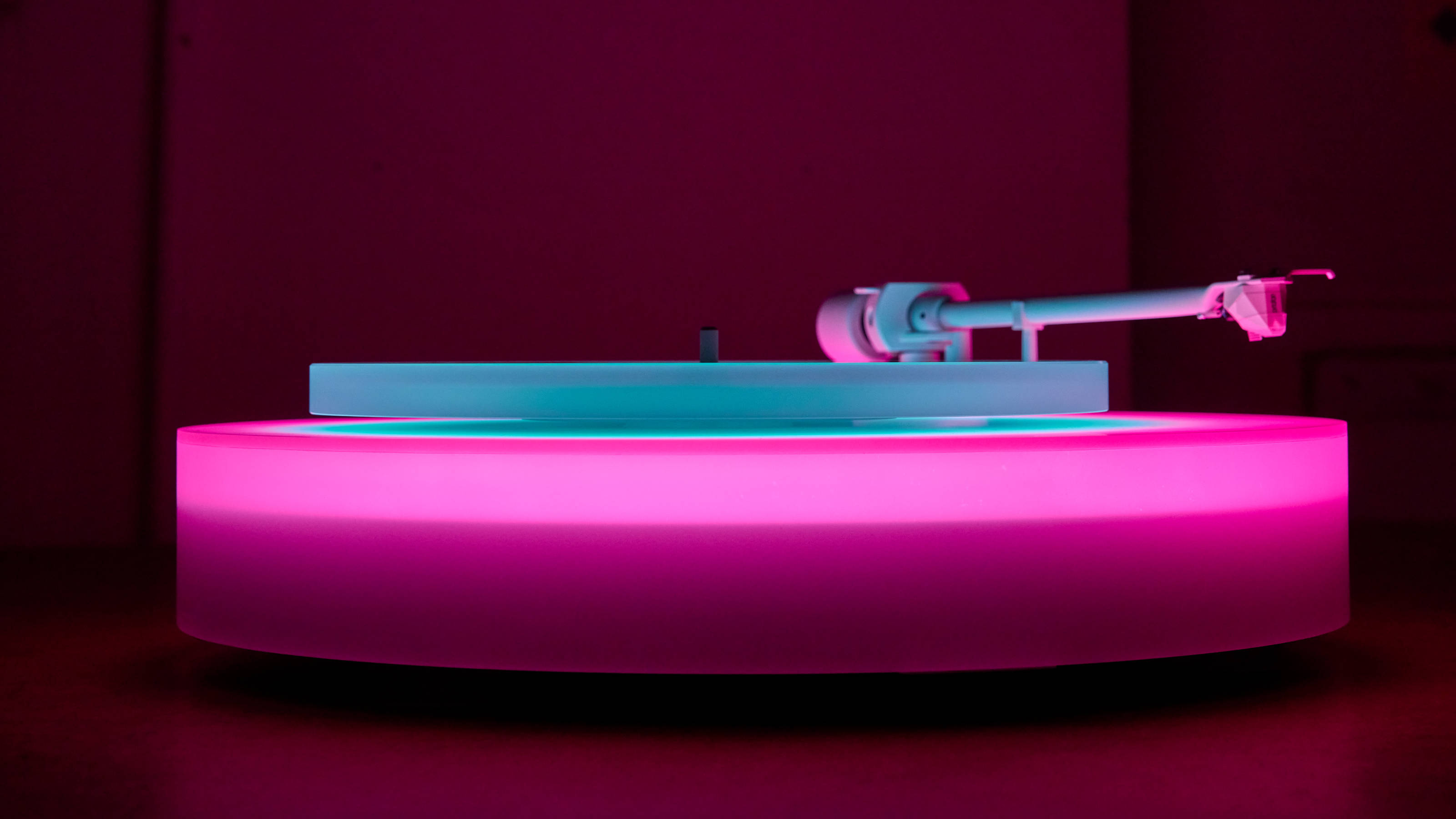

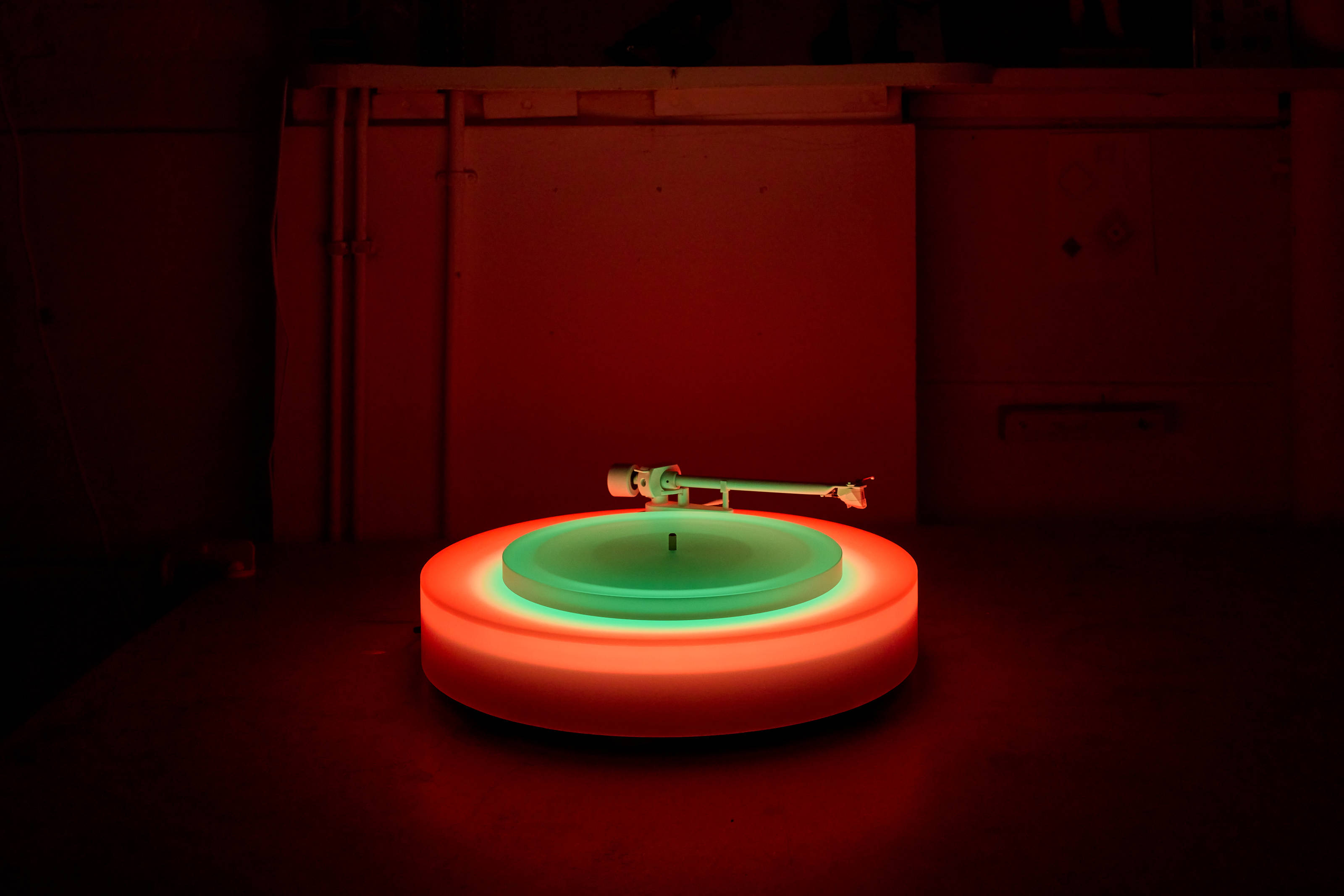

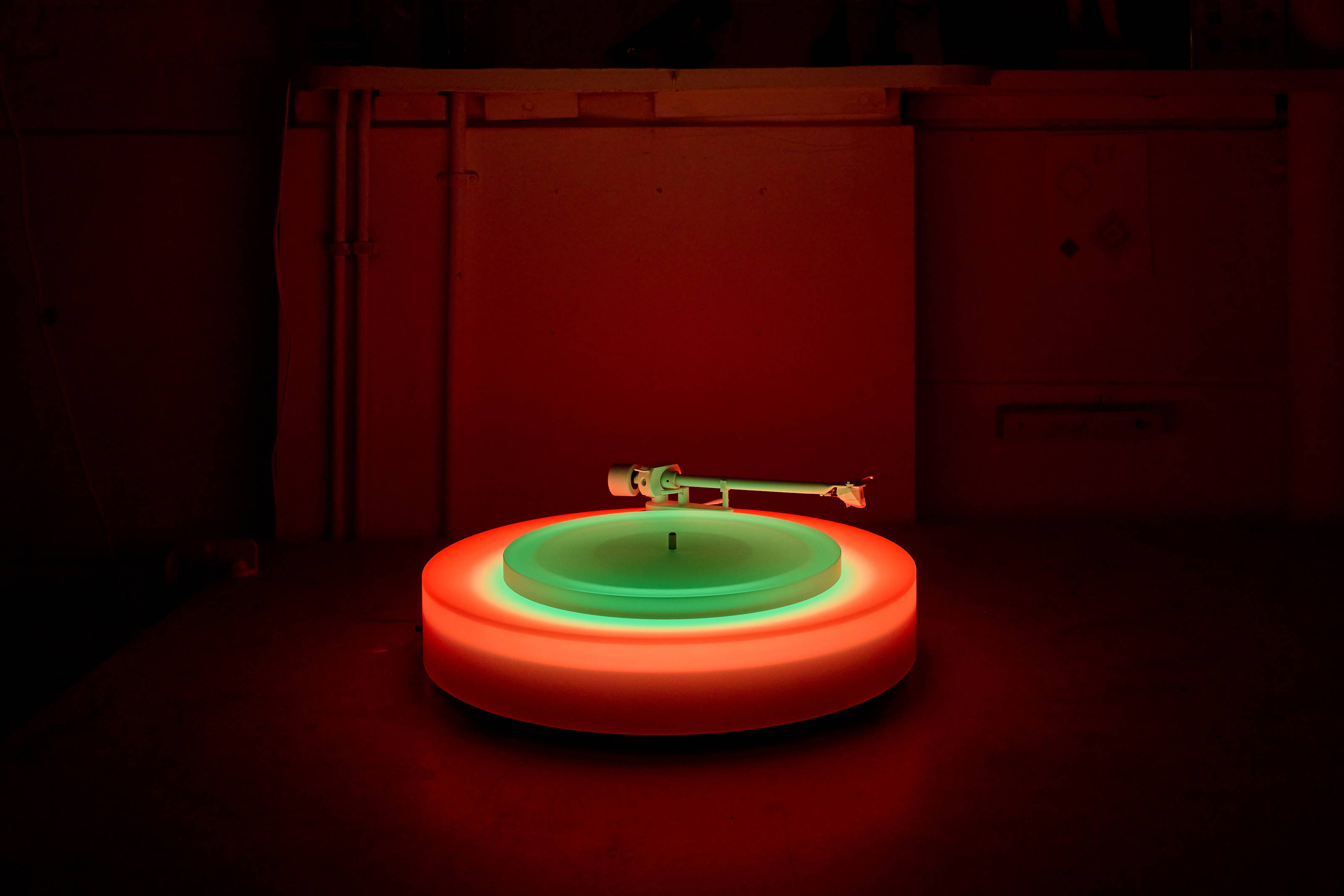

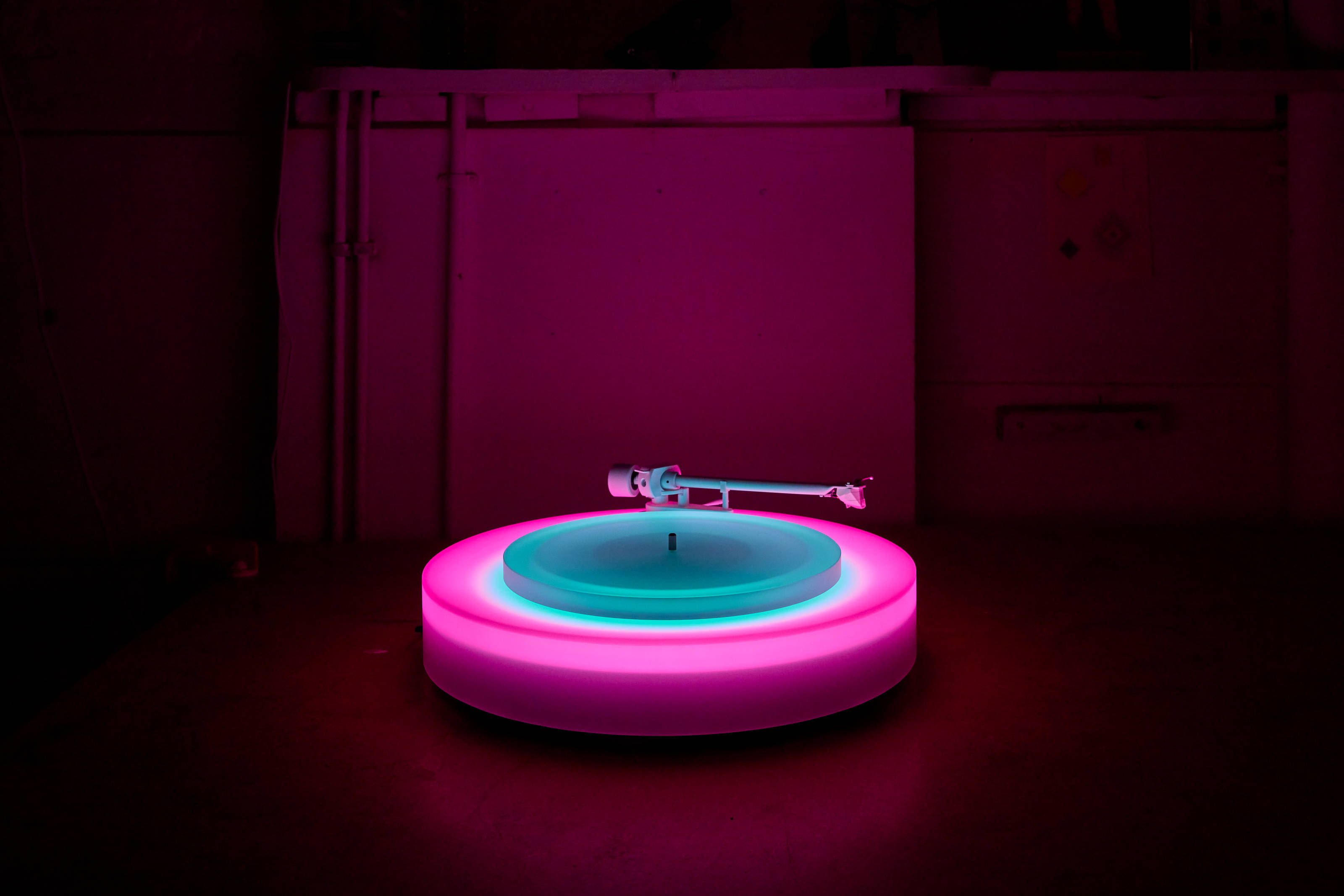

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

Now there’s a sequel. Turntable II is available, once again, from Paul Stolper Gallery – where it is on display until 9 March 2024. As before, it’s a signed and numbered limited edition, with just 150 being made (the first Turntable was made in 50 units). The starting price is £20,000, but the gallery expects that price to rise as it sells through the edition.

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

In contrast to the original edition, Turntable II has a round base as well as a round platter. As before, each translucent form can change colour independently, running through a cycle of preprogrammed ‘colourscapes’. Described by Eno as a sculpture as well as a record player, Turntable II can be deployed as an ambient piece when it’s not playing vinyl. If that’s what you want to do, then the high-quality Pro-Ject aluminium tonearm and Ortofon white 2M cartridge deliver excellent sound quality.

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

On the occasion of the launch of Turntable II, Eno sat down at his studio to talk with the design writer Rick Poynor about the project. We reproduce some exclusive extracts from this conversation below.

Brian Eno talks Turntable II with Rick Poynor, January 2024

Brian Eno with his 'Turntable II', 2024

Rick Poynor: When did you decide to do the original piece and what was its starting point?

Brian Eno: Well, it had a starting point in all these lightboxes you see on the walls here in my studio. What happened in the last few years is that LEDs and the little computers that control them both developed to the point where they were easy for people like me to use. When I started making light pieces, they used incandescent bulbs or even televisions – they were very clumsy, awkward things. In contrast, LEDs are easy to control and very reliable.

The LED lights are diffused through 68,000 holes in the Perspex – they required 44 hours of computer-controlled drilling – to diffuse the light through the surface of the piece.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: How did you know it was going to work exactly how you wanted?

BE: Well, I kind of expected it to; when you scratch Perspex, it suddenly looks very, very bright, because it's catching light that would otherwise be going through between the two surfaces of the material. But I was surprised at how well it worked.

This gave us the confidence to think how we could make other kinds of things, and the turntable was the first example. It was startingly effective – it's the softness of these colours and the way they merge with each other that is so seductive. Ultimately, I just like making lighted objects; someone else suggested a record player; I really liked the idea.

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: These light pieces are an installation in a curated environment – something that goes back to your Quiet Club installations – the more time you spend in these spaces, the stronger the experience is. But with the record player, you have no control over the environment it goes into – how does that change your thinking about the object?

BE: Well, it's the same as the difference between doing a concert and making a record. You don't know what happens to a record after you've made it – somebody could take it home and play it on a fantastic hi-fi or a terrible stereo or through a pair of not very good headphones. Perhaps they’d play it louder than you would, or quieter. So I’m used to the idea that you’re not entirely in control in that medium.

I've seen photographs of how people put the Turntable in their home and it's rather nice – they make it into a sort of shrine. Most of the time I assume it’ll be sitting there like an ornament. It looks great with a 7-inch single on it, actually, as you get this light around the record.

Brian Eno, 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: The turntable seems to bring together at least three things. Firstly, the music, obviously. Then there’s the design side of it. And then there’s the art, in that it’s delivering an experience to do with light and colour and slow change over time. Is it making you think about new possibilities for design objects?

BE: A lot of artists think there's art and then there's design. I don't really think like that. There's art that you just look at and there's art that you do something with. Think of ceramics, for example. Meaning is a funny thing because people never ask these questions about music, unless it's avant-garde, ‘difficult’ music - very few people put on the Beach Boys or Jay-Z and say, ‘What does this mean?’

If there is a message it’s about impermanence and ephemerality and seizing the moment. There are always moments that are disappearing – you can't own this thing completely as it’s never finished.

Brian Eno 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: What’s the value of things that are unfinished or impermanent?

BE: I think that all the things that have made us such a toxic culture come from the idea of saying that something exists and that it is forever and held in place. Nature isn’t like that – it’s constantly changing and in flux. It seems to me to be a very good ecological message. You can't pin it down. You can't own it. It will change. It’s also about seeing everything in your life as a process of becoming, rather than a collection of finished achievements.

Music is a type of change. One of my fascinations is whether you can make paintings that behave like music and don’t stay the same.

Brian Eno 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: Have you encountered a pair of academics and industrial designers called Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby? They started looking at simple objects and working out ways to complicate those objects’ life, like chairs that responded to electrical waves. They coined this term ‘Design Noir’, objects that were slightly troubling and got you thinking. A whole load of theoretical objects have come out of their thinking. Your turntable seems to fit into this lineage of investigation.

BE: It's moving away from functionalism, quite deliberately. I also think what's interesting is to build superfluous properties into objects, like you say.

Brian Eno 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: They’re hybrids that open up new possibilities and provoke interpretation. This is a highly desirable object, but it’s still in the domain of being an exclusive, expensive art object. One could sell thousands probably if you brought the price down. What are your thoughts on that?

BE: I come from a mass media background – making records. But to make these work is actually quite expensive. I'm still not confident that there are thousands of people who want these and to make them cheap and good, they’d probably still be a few thousand pounds – still a luxury item. There's a precarious position between luxury object and mass-produced object. Also, I don't really want to become an industrial maker of record players. I've got plenty of other things I like doing.

Brian Eno 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: There’s still the familiar language of technological objects – they rarely depart very far from the established image of the moment.

BE: Look at the conformity of cars – it amazes me. The zeitgeist very quickly goes through the whole industry. But it also depends on the duration of things. Everything we see on the internet for example goes through very fast cultural change because it’s not going to be part of your life for very long.

Sometimes, though, you just want to have fun. ‘Turntable’ was one of the only things I've ever done that was fun. I mean, some of my early songs were fun and I did them in that spirit, but then it stopped being much of a part of what I was doing. The one reaction I really trust is when I see something and think, ‘Why didn't I think of that?’ Fun has always been a part of pop culture and hardly ever been a part of high culture.

The second turntable actually took quite a long time – the idea of making a circular one that is voluptuous in a way, moving away from the rectangular sharp-edged quality of the first. It's sort of sexier somehow. It was much harder to make as well.

Brian Eno and his 'Turntable II', 2024

RP: The arm is presumably an aesthetic choice – what was the process for that?

BE: We have a white arm, not a black one, which has great visual integration. You get the light coming through the whole object.

RP: So what’s the best music to play on Turntable II?

BE: Reggae sounds good on it. Sly and the Family Stone was actually really good as well.

RP: Have you tried any of your own sounds on that?

BE: I had ‘Discreet Music’ (1975) playing on there once. I thought that seemed to be just the right pace. I haven’t tried any classical music yet. I don’t know what that would be like.

Brian Eno 'Turntable II', 2024

Brian Eno, Turntable II, limited to an edition of 150 worldwide, launch price £20,000 ex VAT, available from Paul Stolper Gallery, 31 Museum St, London WC1A 1LH

PaulStolper.com, @PaulStolperGallery, Brian-Eno.net, @BrianEno

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.