How Lagos’ street markets inspired a new generation of Nigerian creatives

Nigeria’s creative scene is embracing the informal structures used by Lagos market traders as paragons of adaptability, flexibility and identity

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

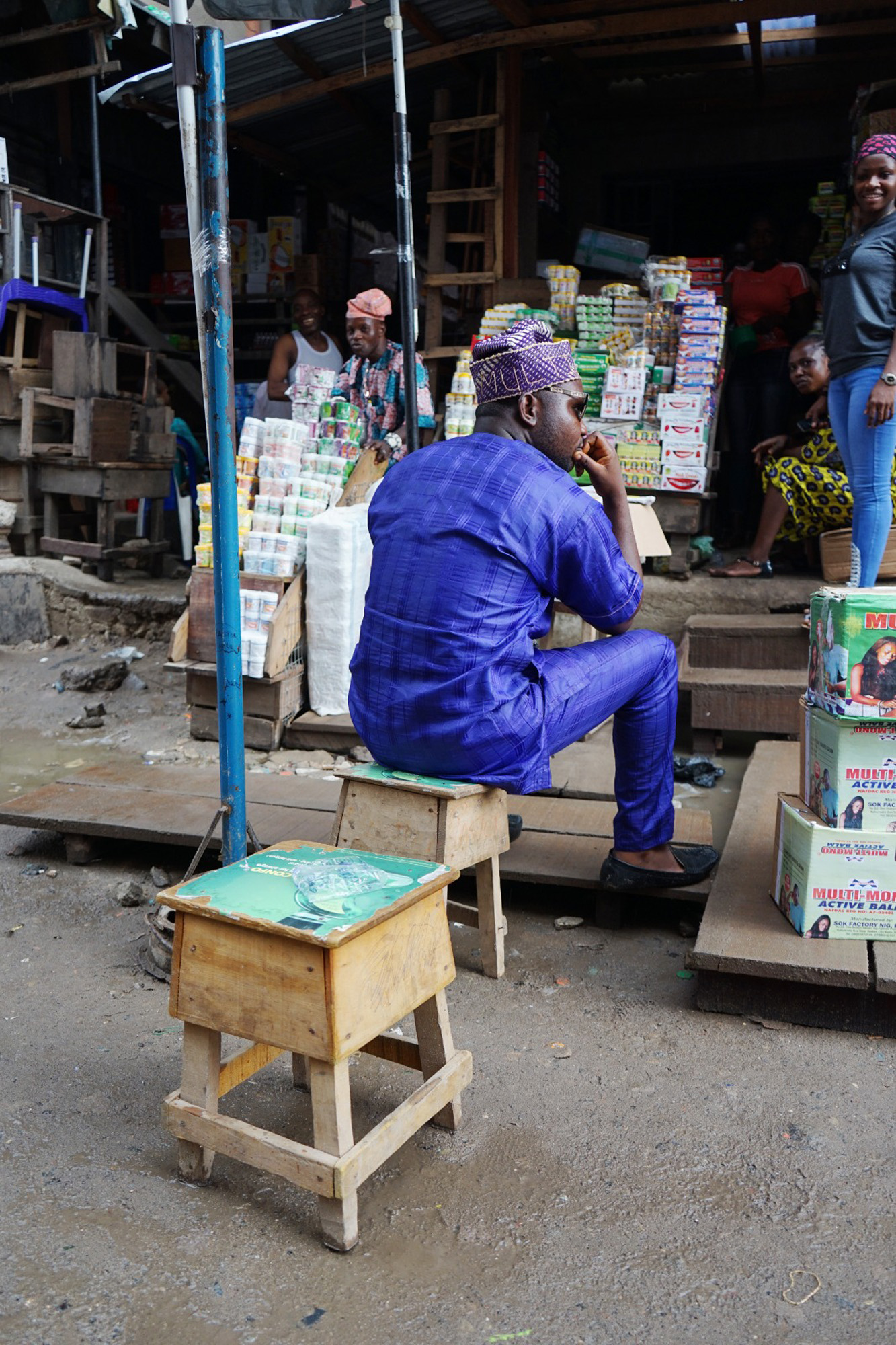

On any given afternoon at Ebute Ero market it can seem as though the entire population of Lagos Island has gathered there. Tailors trudge the streets clinking giant scissors to advertise their services, while women selling the most vivid red tomatoes, spilling out of baskets, call out from corrugated iron-roofed stalls lining the teeming road. Then there are the moving traders with huge loads on their heads, carrying everything from sachets of water and pyramids of dried fish to cardboard boxes piled high.

But despite appearing chaotic, the marketplaces in Lagos are state-structured to a certain extent, says Taibat Lawanson, Leverhulme professor of planning and heritage at the University of Liverpool, UK.

And they play a special role culturally as ‘places of interaction and transaction’, she says. Cultural historian Nze Ed Emeka Keazor also challenges the notion of them as ‘informal’. ‘Many of the market traders are registered companies,’ he says. ‘Virtually all of them pay tax in one form or another to the state government.’

Lagos street markets as design inspiration

Meruwa pushcart

Meruwa pushcarts are used to transport water to houses and businesses

More recently, the Lagos marketplace has become a laboratory for stall design, emerging as an abundant source of inspiration for creatives such as Nifemi Marcus-Bello, who founded Lagos-based design practice Nmbello Studio in 2017. After studying overseas and returning to his homeland in 2013, he was told repeatedly that no one was ‘doing design’ in Nigeria. But his visits to the markets taught him otherwise: his ongoing project researching and documenting market structures and objects has formed the basis of some of his most celebrated design work.

Nifemi Marcus-Bello

The founder of Nmbello Studio, Marcus-Bello’s work draws on African culture and contemporary practices to develop functional objects with a deeply rooted sense of place. He has been researching Nigerian markets for the past ten years, a project involving the documentation of market stall typologies and objects. The portable handwashing station he created in 2020 during the pandemic (which won a 2021 Wallpaper* Design Award and is now held by MoMA) was inspired by meruwa pushcarts, the portable stalls used to distribute water across the suburbs of Lagos.

Marcus-Bello was fascinated by the longevity of the meruwa pushcart he had observed during his childhood in the 1990s and 2000s. The two-wheeled, steel-framed cart, lined with raw planks, is used to carry kegs of water from a central system to households and businesses across Lagos. ‘This for me was an extremely important thing to archive,’ he says. ‘I didn’t realise these things still existed, and they play such a prominent role within the Lagos ecosystem.’ The design principles governing the meruwa were the foundation for a portable handwashing station he created during Covid, winning him a Wallpaper* Design Award for life-enhancer of the year. The modular solution is assembled with easily accessible materials, including a main frame made of tubular steel. Beneath a sink are two kegs – with one supplying clean water while the other takes in wastewater.

Okrika stall

Another prominent market fixture is the okrika stall, a scaffolding-type structure selling secondhand clothing. It is typically built of metal, wood, or a combination of the two. ‘Usually, they’re about 6ft, but I’ve seen ones that are 10ft,’ says Marcus-Bello. ‘I interacted with these a lot as a kid. If you bought bootleg clothing in the 1990s or early 2000s, this is how it was sold.’

Marcus-Bello translated the traditional okrika structure into a contemporary design for Nigerian skate brand Wafflesncream (sometimes known as Waf ). Conceived as a pop-up retail space, the modular kiosk incorporates the brand’s ethos of working with natural and readily available materials, which is reflected in the use of bamboo strips woven around a metal frame.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Nifemi Marcus-Bello

Marcus-Bello has also drawn inspiration from okrika stalls, the stilted contraptions that display clothing for sale. This resulted in the development of a bamboo kiosk for Nigerian skateboard brand Wafflesncream. The designer drew his inspiration from the simple Beninese bamboo blinds known as kosinlé, which are commonly used in homes in the West African city of Porto-Novo.

Umbrellas

Umbrella stalls at Lagos Island’s Balogun market, which is one of the city’s largest and considered particularly good for buying fabrics, clothing and shoes

Umbrellas are ubiquitous at Nigerian markets and are typically added to stalls as flexible shelter from heat and sunlight, as well as rain. ‘Obviously the display mechanism has to be appropriate for this context,’ says architect Tosin Oshinowo, whose research project on Nigerian markets, ‘Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organised Markets of Lagos’, has been on show at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale. Her presentation highlights three of the city’s most dynamic informal markets: Ladipo, Computer Village and Katangua. ‘The way the clothes are displayed is very much an innovation of place,’ she says.

Marcus-Bello highlights that the material make-up of the umbrellas is almost entirely determined by local accessibility. ‘It’s heavily contextual to time, place and availability,’ he says. ‘Some are makeshift, some are ready-made, but the makeshift ones depend on the urban landscape of where they’re going to be used. If there’s a welder close by, the street merchants will work with the welder. That’s why sometimes you see they have a metal structure. Or if there’s a carpentry workshop close by, then the traders will just work with the carpenter.’

The umbrella stalls have also served as inspiration for architectural designer Paul Yakubu, who explored the various ways in which they are used. ‘They’re not owned by the traders, so there’s a basic competition for size of space, and what they use in defining that is the umbrella itself,’ he notes.

On one occasion, he observed three different traders occupying the same site at different times of the day and realised that, in some cases, a joint ownership agreement was in place, with traders sharing some parts of the set-up, such as tables and stools. ‘Under that same structure, a woman was selling bread in the morning and then, from 11am, it switches. There’s a guy doing shoe repairs. He stays until 5pm or 6pm. And then by 6pm, there’s a third person, a woman selling dinner for people on the street. It’s super interesting.’

Paul Yakubu

Yakubu has a master’s degree in architecture and urbanism from the Architectural Association in London. In 2024, he established design research practice Umbrella Arch, which focuses on adaptable design schemes in informal spaces, particularly markets in Nigeria. He created the ‘Umbrella Crate’ stall (pictured), not only in homage to the ubiquitous market stall typology, but also to develop its functionality for small-scale traders. The modular, mobile stall features a circular arrangement of crates around a central umbrella. It can be dismantled and reassembled with ease, and provides adaptability, flexibility and organisation for open markets.

As a result of his research, he developed the ‘Umbrella Crate’ stall, a series of crates stacked in a rotating form sheltered by an umbrella, simplifying the process of assembling and dismantling the structure. The stand maximises space to ensure traders are not limited by their umbrella ratio or forced to spread their wares beyond their defined territory. Furthermore, the trading apparatus is built using discarded plastic crates that have been repurposed, promoting circularity and sustainable principles.

Wooden kiosks

In contrast to the umbrella stalls, where products are openly displayed, there are the wooden kiosks used for financial transactions, or the sale of condiments and household items. ‘Often you just see the trader through the mesh inside this kind of small wooden box,’ Yakubu says. ‘They respond directly to the context. They are super economical to make. Once you limit the customer to outside, there’s the sense of your things inside being secure.’

Marcus-Bello recalls a period of time when many kiosks started being ‘modernised’ and built from fibreglass. ‘The thing about the fibreglass kiosks was they could get extremely hot in the sun, so they didn’t last too long,’ he says. He describes the kiosks as great examples of sustainable modular retail. ‘You don’t have to replace the whole system if a door breaks. You take out the door and you build a new door and you put it in.’

Handheld kiosk

The stall that promotes the most mobility is possibly the handheld kiosk, which is a staple for those who sell their wares on the congested city roads. The design allows the traders to nimbly navigate traffic and approach customers wherever they are. Made from styrofoam and cardboard, with goods secured using thick rubber bands, the kiosks can be rested on shoulders, instead of the weight being borne entirely by the arms. Sellers have the option of buying an empty stall or one loaded with small goods such as confectionery, paying a monthly stipend to the maker and distributor.

‘No one really knows who the originator of the object is,’ says Marcus-Bello, who notes that the way its design has changed over the years illustrates ‘material evolution’ as the city’s markets respond to availability. ‘When I was young, these kiosks were made from plywood because when things were imported, they were often packaged in plywood.

‘If you want to design something that works and is adaptable, [marketplaces] provide some of the best references. Everyone has come together to design, refine and build’

Paul Yakubu

‘Things are now packaged in cardboard and styrofoam,’ continues Marcus-Bello, ‘so that’s what’s readily available.’

Akpoti stool

In her research project, Oshinowo identified another multifunctional object found in market stalls across Nigeria – the akpoti, a stool, made from raw wood planks, that also serves as a table and display stand.

Tosin Oshinowo

Founding architecture and design firm Oshinowo Studio in 2013, Oshinowo is known for her socially responsive approach, with key projects including working with the United Nations Development Programme on a housing scheme for a displaced community in northern Nigeria. She curated the second Sharjah Architecture Triennial in 2023, while her research project, ‘Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organised Markets of Lagos’, for the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale received a special mention. As part of her exploration of Lagos markets, Oshinowo reimagined the akpoti, a multifunctional object constructed from raw wood and used as a stool, table or display stand. Oshinowo elevated its design (pictured) by giving it a black lacquer matte finish, brass bolts and handle to improve its functionality.

‘I sat on one as a child to have my hair done,’ she says. ‘It’s such a common object. It is the most functional design object because it is tried and tested over decades. I started thinking, what if you took this everyday object and you just made it a little bit nicer. How do you take something that is an everyday object and make it something that feels like a design piece?’

Oshinowo reimagined the akpoti carved from wood and painted with a black lacquer matte finish. A side handle was added to improve its functionality, and it is bound with brass nails for a sophisticated take on the rugged staple. Oshinowo says the piece lends itself beautifully to the narrative of the African design context and how anonymously-designed objects are crafted and refined over time by a community.

Water basin

Meanwhile, Salù Iwadi Studio took a conceptual look at the ubiquitous water basin (a multifunctional item used to collect, store and display produce and water in markets), which contributes to conversations around sustainability and reuse. The Nigeria- and Senegal-based design studio built the ‘Water Basin Totem’ to prompt discussions about the object’s use in comparison to the polluting alternative of single-use plastic. Studio co-founder Toluwalase Rufai says the totem reflects the team's sustainable approach to design, from how the products are made and the artisans they employ to the lifespan of the object. ‘Keeping our heritage, our knowledge, and know-how is also a way that we try to champion sustainability,’ he says.

Salù Iwadi Studio

Lagos-based architect Rufai and Dakar-based curator Nassila co-founded design practice Salù Iwadi Studio in 2023, intent on exploring and celebrating Africa’s cultural heritage through design while integrating modern innovation. The pair’s ‘Water Basin Totem’, which showed at the 2024 Dakar Biennale, incorporates a commonplace object found in households and used in markets to store water and agricultural produce. The totem is an art installation that prompts visitors to reflect on plastic waste, and highlights the importance of multifunctional objects, such as water basins, in developing economies.

Yakubu feels that many Nigerian creatives are drawn to marketplaces because the informal space can deliver some interesting lessons on functional design. ‘If you want to just design something that works and is adaptable, these provide some of the best references,’ he says. ‘There’s a communal sense of iteration. Everyone has come together to design, refine and build.’

‘It’s a self-organising system of efficiency without anyone dictating from the top how things should be done’

Tosin Oshinowo

Meanwhile, for Oshinowo, markets provide a platform for what she describes as ‘communal intelligence’, a collective way to design. She says this differs from the contemporary Western context, which is hierarchical. ‘It’s a self-organising system of efficiency without anyone dictating from the top how things should be done.’

Lani Adeoye

Adeoye founded Studio Lani in 2015, focusing on lighting and furniture, and drawing on Nigerian and West African cultural traditions and craft. The Nigerian-Canadian designer uses woven elements in her work, including upcycled leather from Nigerian markets. Her ‘Talking’ collection features hourglass-shaped stools upholstered in eni iran, a floor mat handwoven from the thaumatococcus daniellii plant by women in the south-western state of Ekiti. The textile provides the collection with a natural, organic finish and allows Adeoye to support the region’s traditional fabrication methods.

This article appears in the October 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print and on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Ijeoma Ndukwe is an award-winning writer and journalist based in London. Her work has been published and broadcast on international platforms including the BBC, Al Jazeera and The New York Times.