Sex-positive and radical, these female artists rebelled against the status quo

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Woman is a buzzword in the arts. The thing is, the experience of being a woman is much more complicated than fulfilling a quota. With International Women’s Day and Mother’s Day in the UK coming up (thinly veiled marketing ploys or genuine celebrations of female power, it depends who you ask) Richard Saltoun gallery has staged a group show at its new space on Dover Street of women exploring themselves and other women, through their bodies.

‘Women Look at Women’ focuses on works by 13 artists — mostly European, and mostly black and white vintage photographs (with the exception of sculptures by Helen Chadwick). These baby-boomer women (born between 1935 and 1953) began practising their art at a very different time to the one we stand looking at them today: a carefree 1967 portrait of a smiling Sharon Tate, (two years before she was murdered by the Manson family) by self-taught photographer Elisabetta Catalano, is just one of the markers that gives time away.

Sharon Tate, 1967, by Elisabetta Catalano, gelatin silver print on baryta paper. © Archivio Elisabetta Catalano. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

Other works haven’t dated — because we still face the same prejudices and challenges now as then. The Hackney Flashers founder, Jo Spence, used her Fat Project, (a collaboration with Terry Dennett, shot between 1978 and 1979, and shown for the first time at the gallery) to challenge mainstream representation, the naked fish-eye frolics a reaction to entrenched ideas about how women’s bodies should look, and who should look at them.

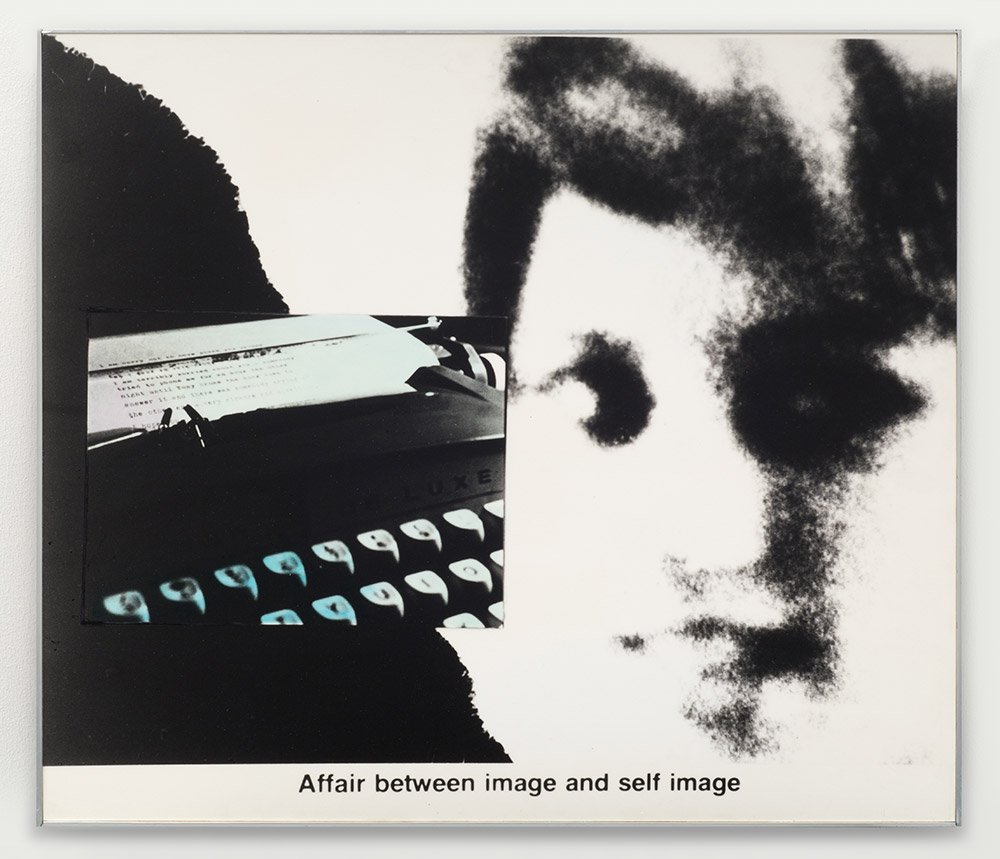

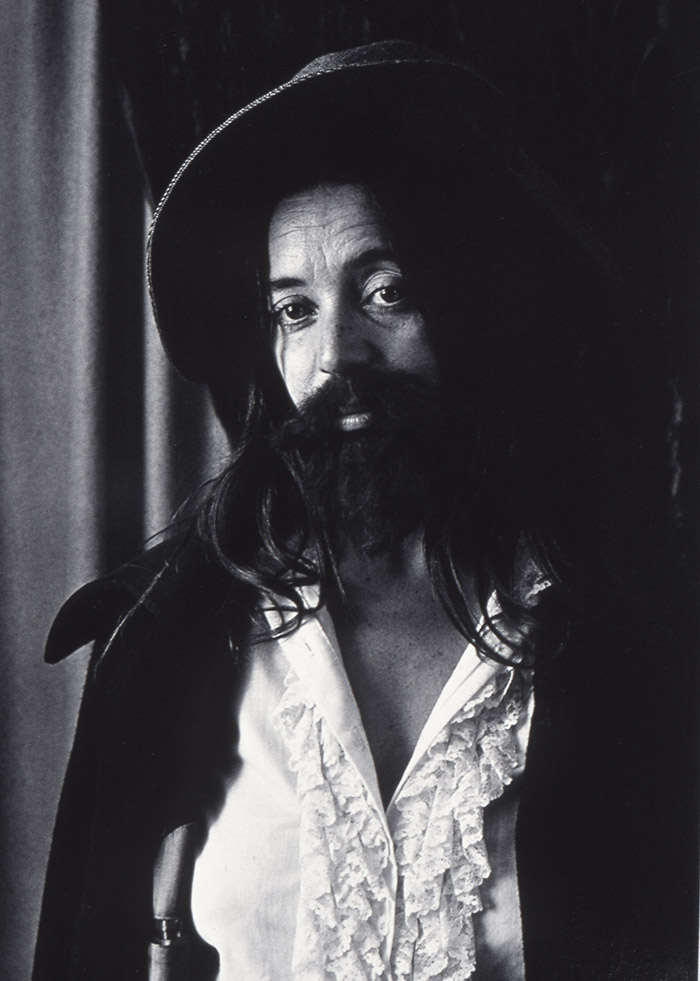

Meanwhile the recently famous Renate Bertlmann’s 1969 work of 53 self-portraits as different female stereotypes, alongside documentation of Eleanor Antin’s 1974 performance as The King of Solana Beach in California, use theatre and performance to show gender is not fixed but fashioned — an idea that has been popularised since they made their works, and not only avant-garde community.

The Missing Woman, 1982-84, Marie Yates, black and white photomontage on board. © The artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

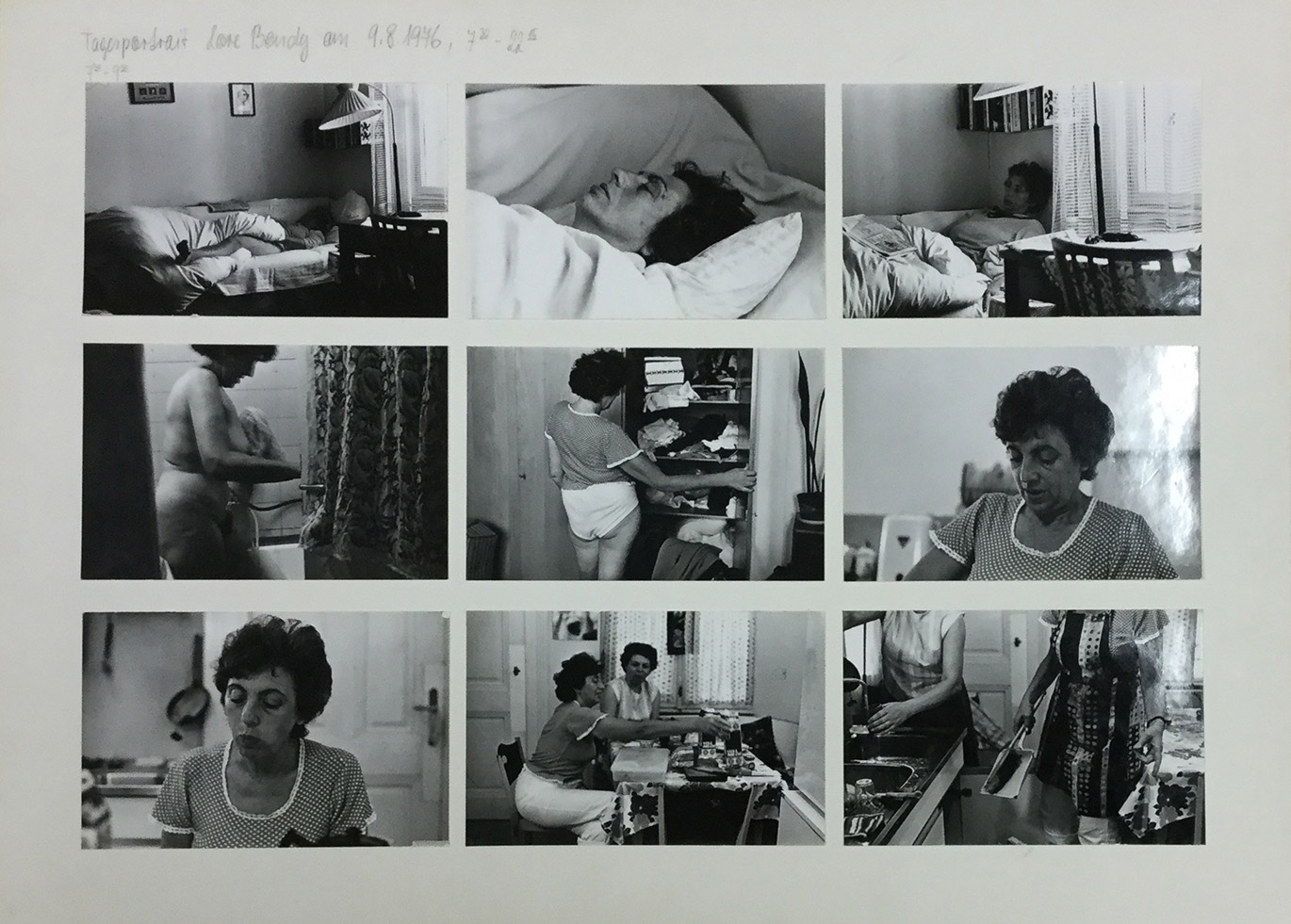

They might have been unpopular in their day, but these artworks were also viewed in their intended context, as they are again now, in the relative safety of the art gallery. If Freidl Kubelka’s Pin-up series (one of the series is included in the display, but more are in the gallery’s archive, if you ask) had first popped up on Instagram, would they have the same veneer of intellectualism, or would she be regarded as ‘just another’ selfie artist? At the time rebellious, sex-positive and radical, looking at the pictures in 2018, they raise questions about the commercialisation of the female body — more relevant now that ever.

Case in point: across town at Galeria Melissa — a project endorsed by the shoe brand — is an exhibition by Juno Calypso, a 20-something artist whose work is directed towards the industry of being a woman, and how we buy femininity. At The Salon, in which she has recreated the ambience of a quotidian beauty parlour, but with a creeping sense of horror, manicures and face masks seem sci-fi. The millennial female gaze, according to Calypso, is stuck on a loop, but we’re narcissistic and we know it.

Portrait of a King, 1972, by Eleanor Antin, black and white photograph mounted on board. © The artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

Bolkan Florinda, 1969, by Elisabetta Catalano, vintage gelatin silver print on baryta paper. © Archivio Elisabetta Catalano. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

Silvana Mangano, 1974, by Elisabetta Catalano, vintage gelatin silver print on baryta paper. © Archivio Elisabetta Catalano. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

The Marxist’s Wife (still does the housework), 1978/2005, by Alexis Hunter. © The estate of the artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

INFORMATION

‘Women Look at Women’ is on view until 31 March 2018. For more information, visit the Richard Saltoun website

ADDRESS

Richard Saltoun

41 Dover Street

London W1S 4NS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.