Shirin Neshat on women’s rights, oppression and the Middle East

Shirin Neshat tells us about ‘The Fury’, a culmination of art and activism, on show at Goodman Gallery, London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The Fury is a new body of work by the Iranian artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat, who is known for her art and activism around being an Iranian woman and an immigrant to America. The London exhibition opened at Goodman Gallery (until 8 November) to coincide with Frieze London 2023, while a virtual reality version of The Fury is showing concurrently as part of the 2023 London Film Festival (until 23 October).

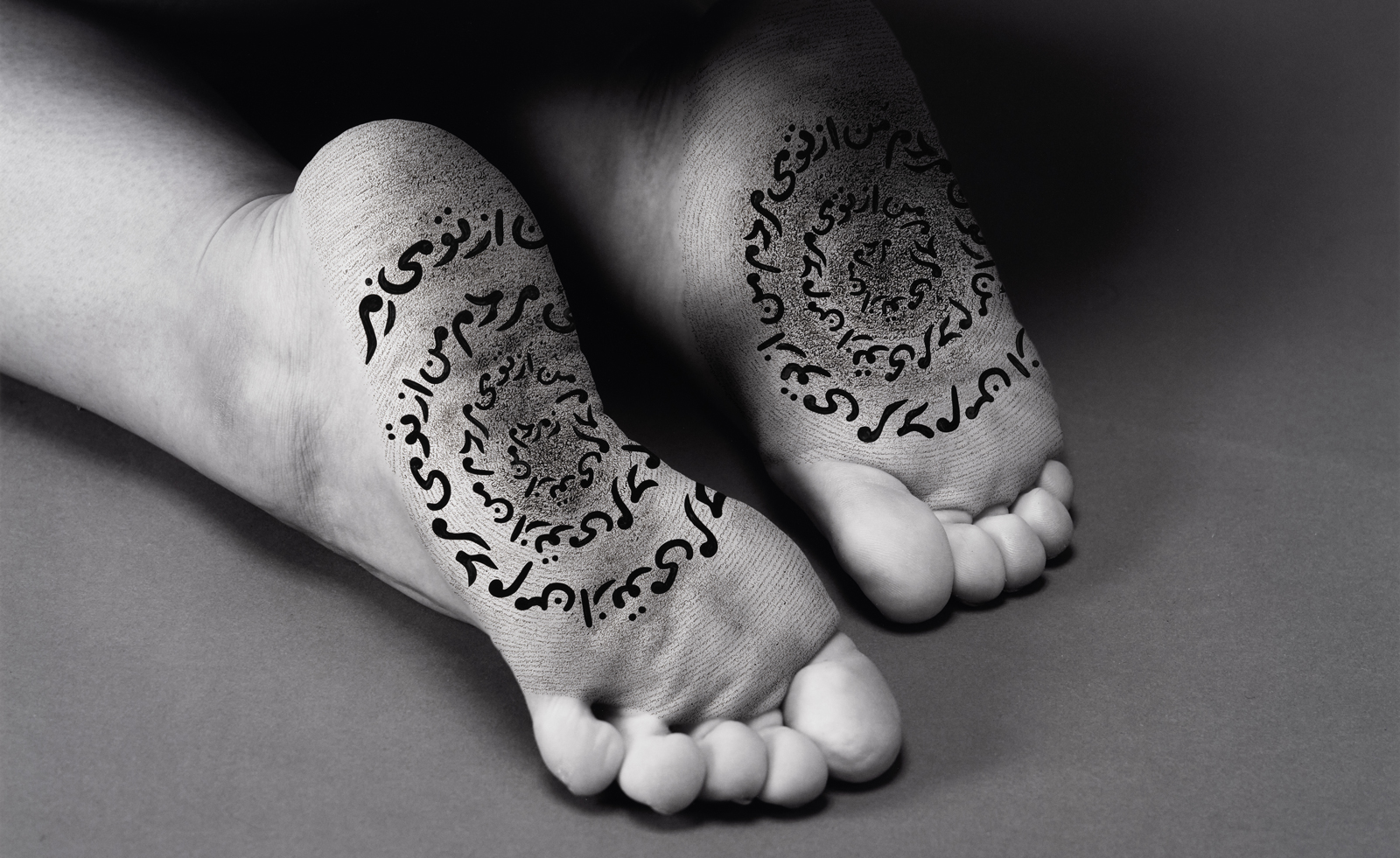

For the first time in a long time, Neshat has turned her lens to the Middle East and is looking at the subject of sexual assault and captivity in Iran. The powerful new works have her signature motifs – striking photography in black and white, combined with handwritten calligraphy in Farsi – but there is a directness that speaks to her earlier work. She is inspired by the Women, Life, Freedom movement in Iran, and is tackling her subject matter head-on.

Neshat left Iran aged 17 and has lived in the United States since then. She began making art in earnest after visiting Iran in the early 1990s, and has since gained a reputation as an important activist voice as well as a renowned artist and filmmaker. She has directed three feature films, Women Without Men (2009), which was awarded the Silver Lion Award for Best Director at the 66th Venice International Film Festival; Looking For Oum Kulthum (2017); and Land of Dreams (2021).

The Fury a is series of photographs accompanied by an 18-minute film shot on the streets of Brooklyn. The works address women’s rights and oppression both in terms of what is happening in Iran and the immigrant experience of those living in the West.

Shirin Neshat on The Fury, freedom and trauma

Shirin Neshat, The Fury, exhibition view

Wallpaper*: This is an entirely new body of work and there is very something different in it both in the technique and in the way that you have presented women. Would you agree?

Shirin Neshat: I think what happened was that [when] I made my first body of work, the Woman of Allah (1994), the photographs of women with guns, people came right at me because it was so directly political and very critical of the government, the people of Iran, everybody. And then [I] moved towards this far more evocative, or more poetic way of working. This work goes back to that because I think it's the most political work I've done in a long time because I just couldn't help it.

W*: What made you want to make The Fury now? You have mentioned in previous interviews that you wanted to unleash rage, why is that?

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

SN: First, I wanted to say that this film was made in June of 2022, just so you can recall when Mahsa Amin was murdered. That unleashed rage; all these women were bottled up all this time, but the fact [was] that she was murdered just because some of her hair was showing. Sometimes we need victims to be reminded of how angry we are about racism, about injustice, about economic injustice, about political injustice.

I shot this, where I live, which is all immigrants, it's all Hispanic, African and Asian immigrants and working-class people. This is my community. The dancers are from my dance class and the choreography was done by my African dance teacher. I feel like, you know, they all understood what I was coming from with this idea of the story. Every one of them has suffered, every one of them [is] still dealing with money issues, racism, injustice from their home country or American culture. There is this sense of solidarity. We may not even speak the same language but there is love there. I no longer live in Iran; I live in New York, and this is my community.

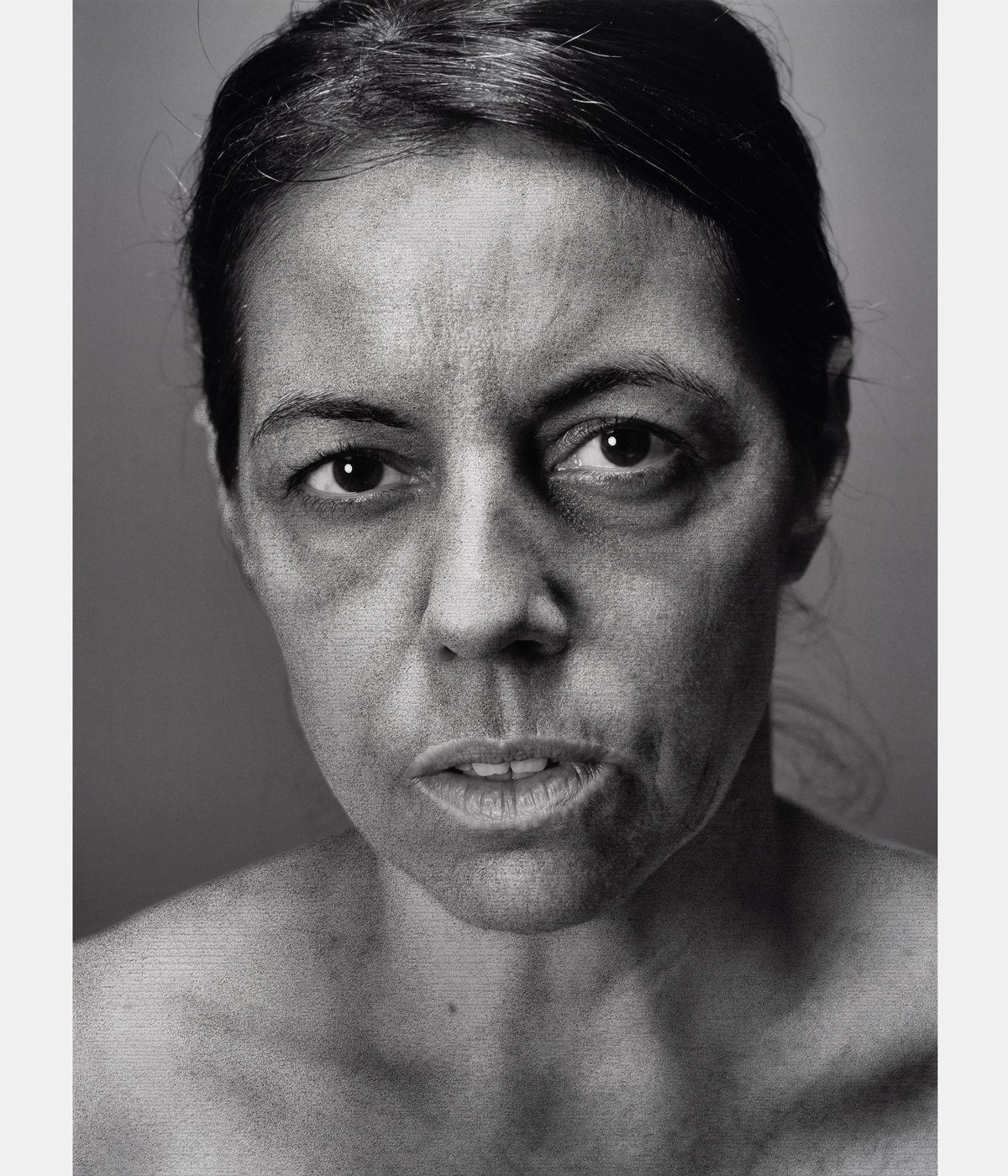

Shirin Neshat, Ana #2, form The Fury series, 2023

W*: For The Fury, you take a motif from the famous bar scene in the 1974 film directed by Liliana Cavani, The Night Porter. Why did you choose this as a reference?

SN: I've long been obsessed with the subject of the relationship between the captured versus the capturer and Stockholm Syndrome; sometimes those who are captured and no longer have control of their freedom end up making peace in some ways with their situation. I've even known women political prisoners who fell in love with their interrogators and slept with them; one of [the women’s interrogators] let her go free on the condition that she would always call him – a very weird relationship.

So, I’m concerned with the subject of when your life is no longer in your own control and the question of freedom. And also, I think it's commonly known that when you really want to break somebody's back, you sexually exploit them. I think with that film, it really, really stuck in my mind, in a way that the relationship of the main characters and my country, in the way that the Revolutionary Guard, our biggest nightmares, and the same people who are men of religion, are the same people who rape and do the most inhuman things to young men and women.

I think as someone who's on the outside and always immersed in Western cinema and art, I just reflected on my own culture and the universality of those who are in power, and uniform and how they can inflict pain, and [also on those] of us who are powerless.

Shirin Neshat, The Fury, exhibition view

W*: The music is also an important part of the film – tell us more.

SN: The music was actually originally a Persian song, but [the lyrics were rewritten and] can be read as if you're talking about individual freedom, or national freedom. It was improvised over the top of the film live.

W*: Why was this the right time for The Fury?

SN: I'm tired of always living in nostalgia, making work about Iran that is about looking back to a culture that I can't even go back to. There's so much to say about American culture. You know, I'm walking around Bushwick listening to my Persian music, looking at all these people going to work. And they're like different types of ethnicities.

I wanted this story to be about an Iranian who is free but even in freedom, she cannot recover from trauma. I also carry a lot of baggage. I've been separated from my family for so many years.

Everyone has trauma. I think to me, this work was as much about this as it was about sexual assault.

Shirin Neshat, Daniela #2, from The Fury series, 2023

W*: How you choose the subjects for the photographic works?

SN: I worked with a friend who was not a casting agent. And she did the job of recruiting women from different generations, different sizes and different ethnicities. I wanted them to be comfortable with the subject because it's a very delicate subject. What happened was these ladies came, I explained to them that I wanted them to feel comfortable, that this is a subject about women equally as an object of desire, but also as an object of violence. I said, we're going to film you as fully competent and defiant and proud and beautiful as you are.

W*: There is a powerful unifying force around this work. Can art be an act of solidarity?

SN: First of all, as a minority immigrant person of colour living in the US, it's a very complex situation. It takes me away from being Iranian and it makes me a second citizen in the US; since the age of seventeen, [I've been] alone in this country without my family. So, I'm not completely Iranian, I'm an immigrant American and I relate to other minorities in America.

The Fury is on view at Goodman Gallery, London until 8 November 2023

Amah-Rose Abrams is a British writer, editor and broadcaster covering arts and culture based in London. In her decade plus career she has covered and broken arts stories all over the world and has interviewed artists including Marina Abramovic, Nan Goldin, Ai Weiwei, Lubaina Himid and Herzog & de Meuron. She has also worked in content strategy and production.