Robert Mapplethorpe: the young wanderer’s early years

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Polaroids taken from Robert Mapplethorpe’s early years in the Chelsea Hotel with lover and patron Patti Smith are going on show for the first time, detailing the beginnings of the soon-to-be famous photographer’s signature minimalist style.

Holed up in Manhattan’s Chelsea Hotel, penniless and surviving off candy bars, Mapplethorpe would convince Smith to buy him Polaroid film. Once he had loaded the camera, he would take off, walking the streets alone. ‘We were both praying for Robert’s soul,’ Smith wrote in Just Kids, her 2010 memoir of their time together. ‘He to sell it and I to save it.’

A new exhibition is showing, for the first time, the Polaroids that Mapplethorpe took on those walks. Hand-selected from the archive belonging to the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation in New York, they shed light on a pivotal early phase of the photographer’s now iconic 20-year career. The exhibition, at Weinstein Hammons Gallery in Minneapolis, Minnesota – and soon to make its way to San Francisco Photofairs from 22 February – includes Mapplethorpe’s early Polaroids alongside silver gelatin prints taken in his studio in the years before his death of AIDS in 1989.

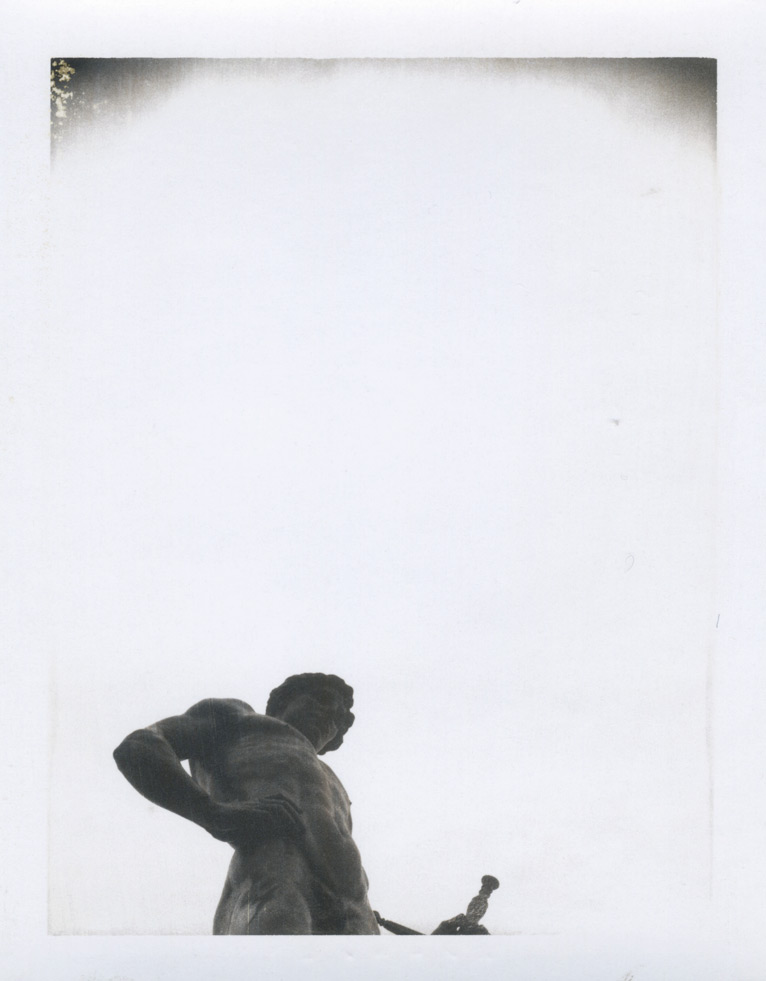

Untitled, c 1973, by Robert Mapplethorpe, vintage Polaroid. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe’s signature style was always apparent, regardless of subject or era. Be it the contours of a muscular man or the curves of a bottle of wine, a lonesome telegraph pole or the arching stem of a lily, Mapplethorpe captured his subjects with an obsessional and exacting formal care. Each image was a perfectly weighted composition of crepuscular lights, shimmering whites, eggshell greys and velour darks.

In 1988, a year before his death, Mapplethorpe said: ‘Even the earliest Polaroids I took have the same sensibility as the pictures I take now. Right from the beginning, before I knew much about photography, I had the same eyes. When I first started taking pictures – the vision was there.’

‘Mapplethorpe had this singular ability to capture very hot imagery with this very cool detachment,’ Leslie Hammons, co-director of the gallery and curator of the show, tells Wallpaper*. ‘He was a complicated person – he had his family issues, and this ongoing, complicated relationship with the Catholic church. Those themes were ever-present in his work, from the early Polaroids right through to the work he made in the years before his death.’

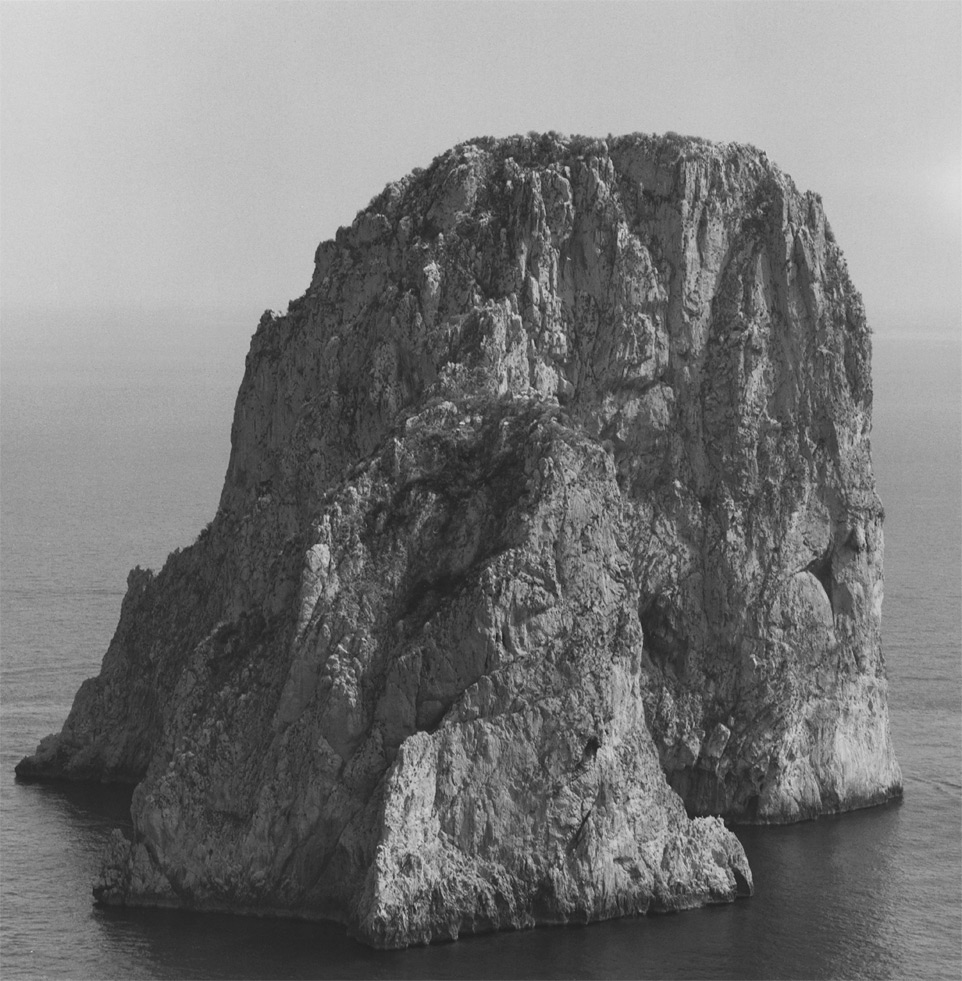

Mountain, 1983, by Robert Mapplethorpe, gelatin silver print. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

‘Suburbia is a good place to come from,’ Mapplethorpe once said. ‘And a good place to leave.’ He was born in 1946 in Floral Park, a middle-class neighbourhood of Queens. On Sundays, he and his five brothers and sisters would attend the local church. In 1957, as Robert neared puberty, homosexuality was still officially classed as a disorder by the American Psychiatric Association. Later, when he came out, his father refused to speak to him. ‘Mapplethorpe’s family had difficulty comprehending the differences in Robert’s lifestyle to that of their own,’ Hammons says.

He told his parents he was going to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn to study advertising, but quickly switched to painting and sculpture. He started taking drugs and dressing as he felt. Two years later, in 1969, Mapplethorpe dropped out of school and, along with Smith, set-up permanently in downtown Manhattan.

By 1971, Mapplethorpe’s experiments with Polaroids had evolved into a full-time focus on photography, one he used to capture the emerging gay scene at its most liberal. ‘He worked without apology, investing the homosexual with grandeur, masculinity and enviable nobility,’ Smith wrote in Just Kids.

Soon he would meet and fall in love with the art collector Sam Wagstaff, whom would provide the young artist with a decked-out studio, a gateway into the established art scene (including a strained mentorship with Andy Warhol) and, crucially, an ‘in’ with the moneyed circles of the Upper West Side. His pathway to the mainstream was now paved with gold, his fame assured. But, in those early disposable images, taken on the streets when no-one knew his name, the signature of a world-changing artist was already there, and already beautiful.

Untitled, c 1973, by Robert Mapplethorpe, vintage Polaroid. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Texas Gallery, 1980, by Robert Mapplethorpe, gelatin silver print. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

INFORMATION

‘Robert Mapplethorpe’s Minimalism’ is on view at Weinstein Hammons Gallery until 3 March, and launches at San Francisco Photofairs from 22 February. For more information, visit the Weinstein Hammons Gallery website and the San Francisco Photofairs website

ADDRESS

Weinstein Hammons Gallery

908 West 46th Street

Minneapolis MN 55419

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.