Passage of time: Richard Long retrospective opens at Bristol Arnolfini

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Richard Long has the healthy mien of a man who gets out of the office. Indeed, at 70 he has succeeded in doing the bulk of his life’s work on the road. Dressed in hiking gear and possessed of a deep, mid-summer tan, he says with understatement, ‘I’m not a studio artist,’ looking very much the Thor Heyerdahl of the art world.

Long is speaking at Bristol’s Arnolfini gallery, ahead of the launch of ‘Time and Space’, a survey of his landscape sculpture going back some 50 years. Since his days at the University of the West of England in the mid-1960s, he has undertaken marathon walks (‘quite pleasurable, really’) around Bristol, progressing to Nepal, Bolivia and Antarctica, marking his way in the local stone and dirt. Many of those ephemeral works appear in the Arnolfini’s five sunlit rooms, mostly as textual and photographic reminders of his endeavours.

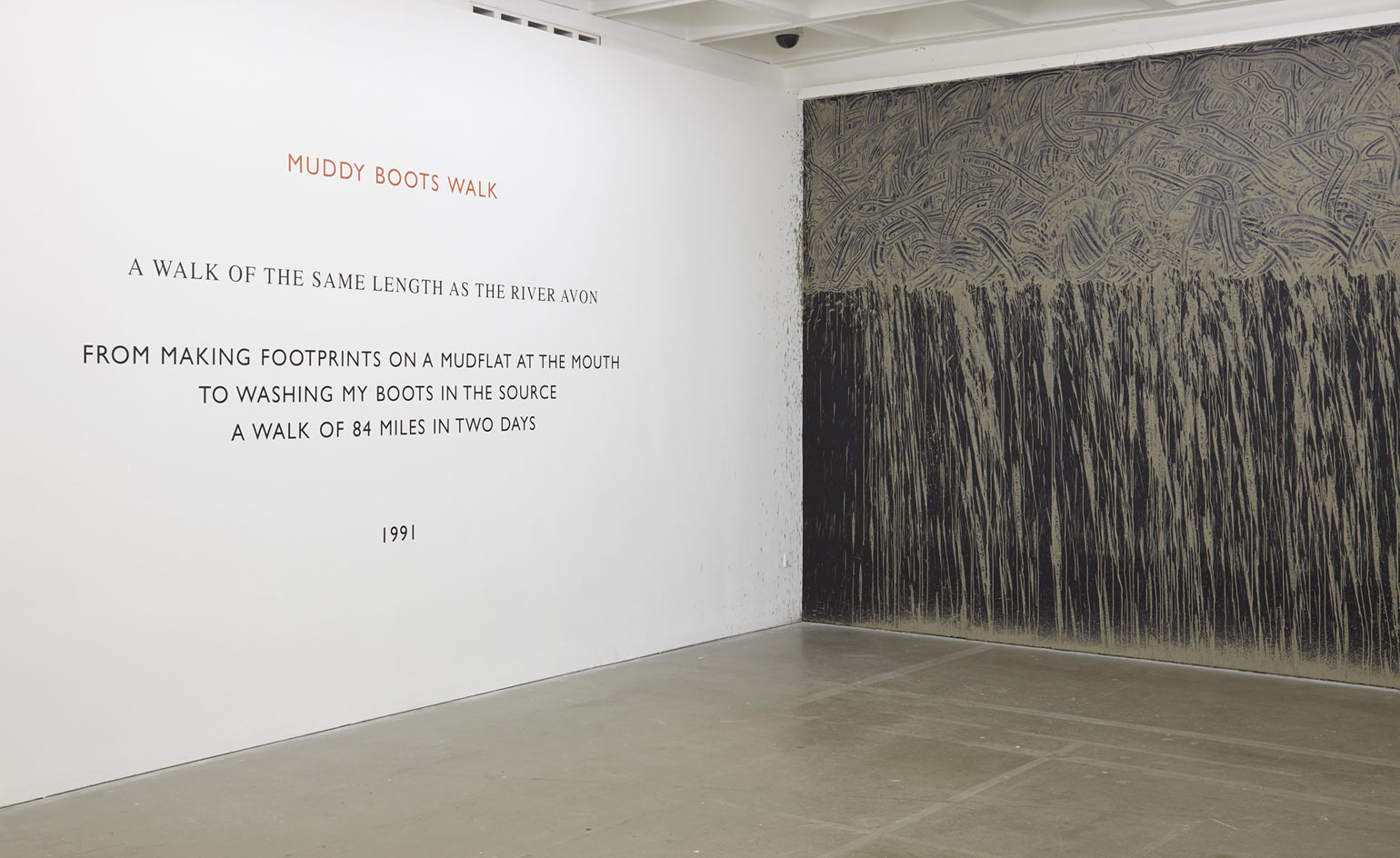

In the 1980s, Long was nominated four times by the Turner Prize committee for his primitively styled environments, finally winning in 1989 for White Water Line, a meandering path traced in china clay. Here, he takes visitors on a longer journey. It begins with a vast monochrome photograph of A Line in the Himalayas, 1975, an eerily straight route in ancient stone across a barren plateau. Leading into the main gallery are hand-painted textual ‘illustrations’ of his West Country endeavours. In Mud Walk, 1987, he inserts precise distances into prose that takes a haiku-like rhythm.

‘A 184 mile walk from the mouth of the River Avon / to a source of the River Mersey / casting a handful of River Avon tidal mud / into the River Thames the River Severn / the River Trent and the River Mersey / along the way.’

‘The balance of measurements,’ says Long, ‘is important to the work.’

The progression through to Muddy Water Falls, 2015 – first conceived in 1984 but here recreated as mural of Avon mud that Long splattered in situ in a frenetic 45 minutes – is heavy of foot. Watching all those miles tick over, it’s difficult not to think of Cheryl Strayed’s journeywoman memoir Wild.

The first-floor rooms are bracketed by two epic installations. The first, a target of concentric circles titled Bristol, was first constructed in 1967 and hauled to Ireland before taking shape here. Next door is the titular new Time and Space, a monumental cross in interconnected shards of Cornish slate, branding the gallery like a leaden foot on the Moon.

The real adventure of the show, however, is the satellite work Boyhood Line. A few miles from the Arnolfini, on the Bristol Downs, Long has found a well-trod path across fields where he played – and then worked – in his youth. He’s traced it with hundreds of heavy, chalky stones that seem to transcend the horizon (though in reality the trail is easily and quickly walkable). Boyhood Line marks a full-circle moment for an artist who has worked with the earth for well over half a century. ‘I don’t have a choice,’ he says. ‘The landscape of the South West, the country lanes – that’s my territory.’

Since the mid-1960s, Long has undertaken marathon walks around Bristol, progressing to Nepal, Bolivia and Antarctica, marking his way in the local stone and dirt. Pictured: Muddy Water Falls, 2015. Photography: Stuart Whipps

Time and Space, 2015, a new work, is a monumental cross in interconnected shards of Cornish slate, branding the gallery like a leaden foot on the Moon. Photography: Stuart Whipps

The concentric work Bristol was first conceived in 1967, then hauled to Ireland before taking shape here. Photography: Stuart Whipps

Walking is the central tenet of Long's practice; his recordings are often supplemented with spare, poetic textual passages that include exact details on distances. ‘The balance of measurements,’ says Long, ‘is important to the work.’ Pictured: Muddy Boots Walk, 1991. Photography: Stuart Whipps

The real adventure of the show is the satellite work Boyhood Line, 2015, located on the Bristol Downs a few miles from the Arnolfini. Photography: Max McClure

Long, with hundreds of heavy, chalky stones, has traced a well-trod path across fields where he played – and later worked. Pictured: Boyhood Line, 2015. Photography: Max McClure

Richard Long with Boyhood Line, 2015. Photography: Max McClure

ADDRESS

Arnolfini

16 Narrow Quay

Bristol, BS1 4QA

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Based in London, Ellen Himelfarb travels widely for her reports on architecture and design. Her words appear in The Times, The Telegraph, The World of Interiors, and The Globe and Mail in her native Canada. She has worked with Wallpaper* since 2006.