Jean-Michel Basquiat meets Egon Schiele in parallel Paris retrospectives

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Since opening three years ago, the Fondation Louis Vuitton has become a destination for blockbuster exhibitions. The museum’s latest programming is once again a tour de force, in part because it consists of two comprehensive retrospectives: one dedicated to Egon Schiele, the another to Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Featuring upwards of 100 works per artist, including myriad masterpieces and rare loans from public institutions and private collectors, the shows have been mounted separately; and it’s entirely possible that those who visit the foundation will opt to take in one without the other. But to do both as a double-bill is to experience a unique bombardment of creation and self-expression from a pair of talents whose differences and similarities prove a thrilling match.

Paris has not had a Schiele exhibition in 25 years, and 2018 happens to be the centenary of his death. The idea to feature him, however, only came about after the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s head curator, Suzanne Pagé, began discussing a Basquiat retrospective with guest curator Dieter Buchhart, as the artist has been personally collected by foundation president (and LVMH chief), Bernard Arnault.

In 2014, Buchhart, an expert on Basquiat, had staged an exhibition at Nahmad Contemporary in New York that established a stylistic narrative between Schiele, Basquiat and Cy Twombly, where their works appeared adjacent to each other. Here, as separate exhibitions, the comparative aspects of youth, obsessional output and what Bucchart calls the ‘existential line’, are ever-present yet mostly serve to underscore the artists’ independent virtuosity.

Installation view of ‘Egon Schiele’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. © Fondation Louis Vuitton

‘We wanted to make an exhibition about something which is just so crucial for these artists,’ says Bucchart, who describes the existential line as a particular manifestation of fear and anger. ‘Very obviously, it was a tool for them, but this has never been made clear in a show.’

Both artists died at the age of 27 towards either end of a century defined by global political upheaval and unparalleled social and technological progress. Interestingly, throughout their brief but prolific careers, they both forged close bonds with an older master artist — Gustav Klimt for Schiele and Andy Warhol for Basquiat. What seems especially remarkable is that the totality of their work exists beyond established movements or codes, making it profoundly timeless and relevant today. ‘We will never know what would become of them but they left an oeuvre that was complete,’ notes Bucchart.

As a complete exploration, visitors are encouraged to first descend to the lower level galleries, where they begin with Schiele, whose works in pencil, crayon, gouache and watercolour on tinted paper tend to depict a single figure occupying a small to medium-sized frame. Sometimes they inhabit a total void, other times they emerge like recollections delineated by his familiar white surround.

No matter the degree of distortion or disfigurement, seduction or repulsion, the composition comes across as deliberate and controlled. His application of colour, even in his larger paintings, is minimal but emphatic. And his self-portraits of cut-off heads are searing in intensity (Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat, Standing, meanwhile, registers as wonderfully elegant).

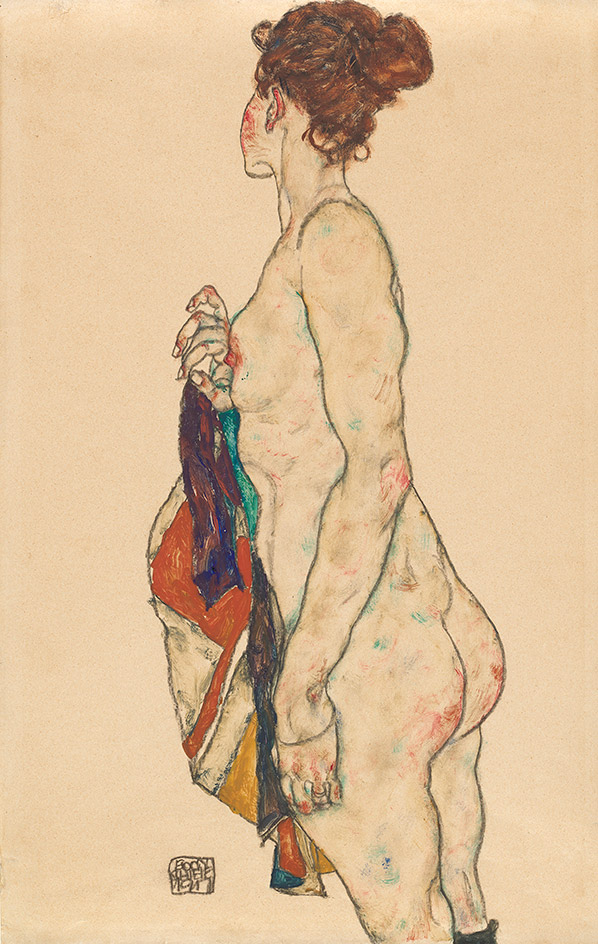

Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat, Standing, 1911, by Egon Schiele, gouache, watercolour and black crayon on paper. Courtesy of Ernst Ploil

Exiting Schiele and entering into Basquiat presents a wholly different representation of self, society and style. The walls shift from an ochre-ish yellow to white as the latter’s explosive canvases, namely a trio of heads, seem to shout and throb. Imagine suddenly switching a playlist from Schoenberg to Fab Five Freddy, cranking the volume high and you get the idea. And from this level up through the second floor, the galleries reveal different facets of Basquiat’s output, with works grouped by themes as ‘Heroes & Warriors,’ ‘Words,’ ‘Music Spoken,’ and ‘Basquiat and Warhol,’ where their collaboration is crystallised by a number of lively, extra-large canvases.

Buchhart points to the section titled ‘Knowledge Spaces’ as a microcosm of Basquiat’s forward vision, for it is here that visitors can sense the interconnections between symbols, pictograms, deletions and additions, and chaotic bytes of detail as compositions not unlike the internet where information can feel simultaneously sorted and wildly random.

In Radiant Child, a documentary on Basquiat by Tamra Davis, the artist who began by spraypainting messages on New York walls under the alias, SAMO, categorically dismisses the question of how he describes his work. ‘I don’t know how to describe my work’ he tells her. ‘It’s like asking Miles (Davis) how does your horn sound. I don’t think he can really tell you why he plays this at this point in the music. It’s automatic most of the time.’

Untitled (Boxer), 1982, by Jean-Michel Basquiat, acrylic and oilstick on canvas. Licensed by Artestar, New York

But that’s not to suggest visitors shouldn’t arrive at their own conclusions, whether by homing in on his questioning of race, his political and economic commentary, his depictions of self, and the breadth of his references. Seeing Irony of a Negro Policeman, Boxer, Napoleonic Stereotype Circa ‘44, Now’s The Time, Horn Players, Pez Dispenser, Gold Griot, and finally, Riding with Death (a haunting anomaly of a canvas painted shortly before his death) is to marvel at his wide-ranging exploration of subject matter, internal dialogue and dynamic style.

Says Bucchart of Basquiat, although equally applicable to Schiele, ‘He was not a wild painter at all. In the end, his compositions always had something to do with intuition and talent. In my understanding, it’s actually fine if he’s not able to explain what he’s doing. He gives us a job. We are able to think about his work and that’s a great thing.'

Installation view of ‘Jean-Michel Basquiat’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. © Fondation Louis Vuitton

Autumn sun (Sunflowers), 1914, by Egon Schiele, oil on canvas.

Installation view of ‘Egon Schiele’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. © Fondation Louis Vuitton

Standing Nude with a Patterned Robe, 1917, by Egon Schiele, gouache and black crayon on buff paper. Washington

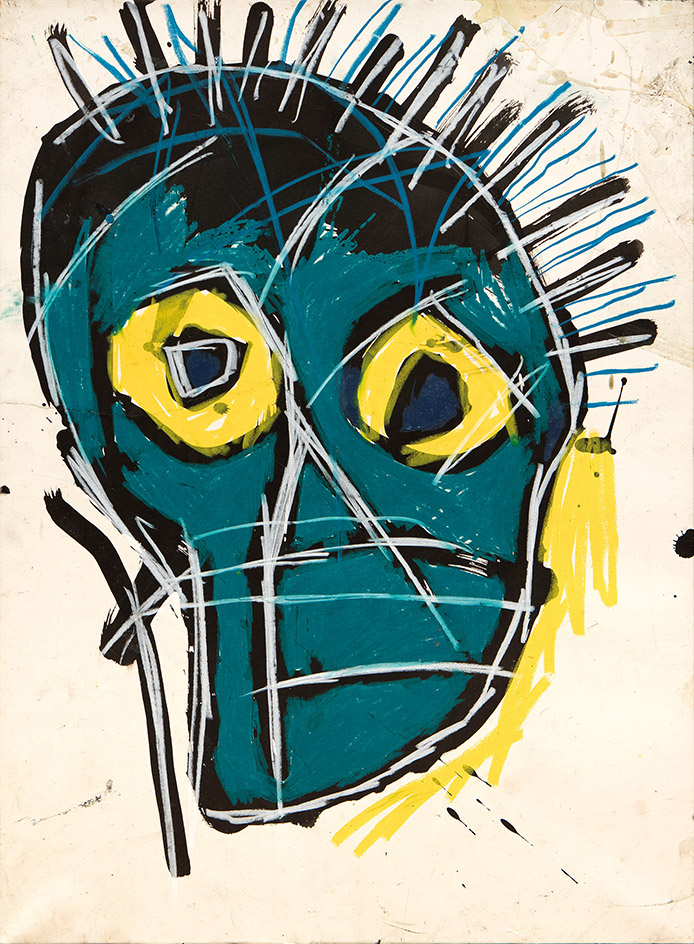

Untitled, 1982, by Jean-Michel Basquiat, acrylic and oilstick on paper. Licensed by Artestar, New York

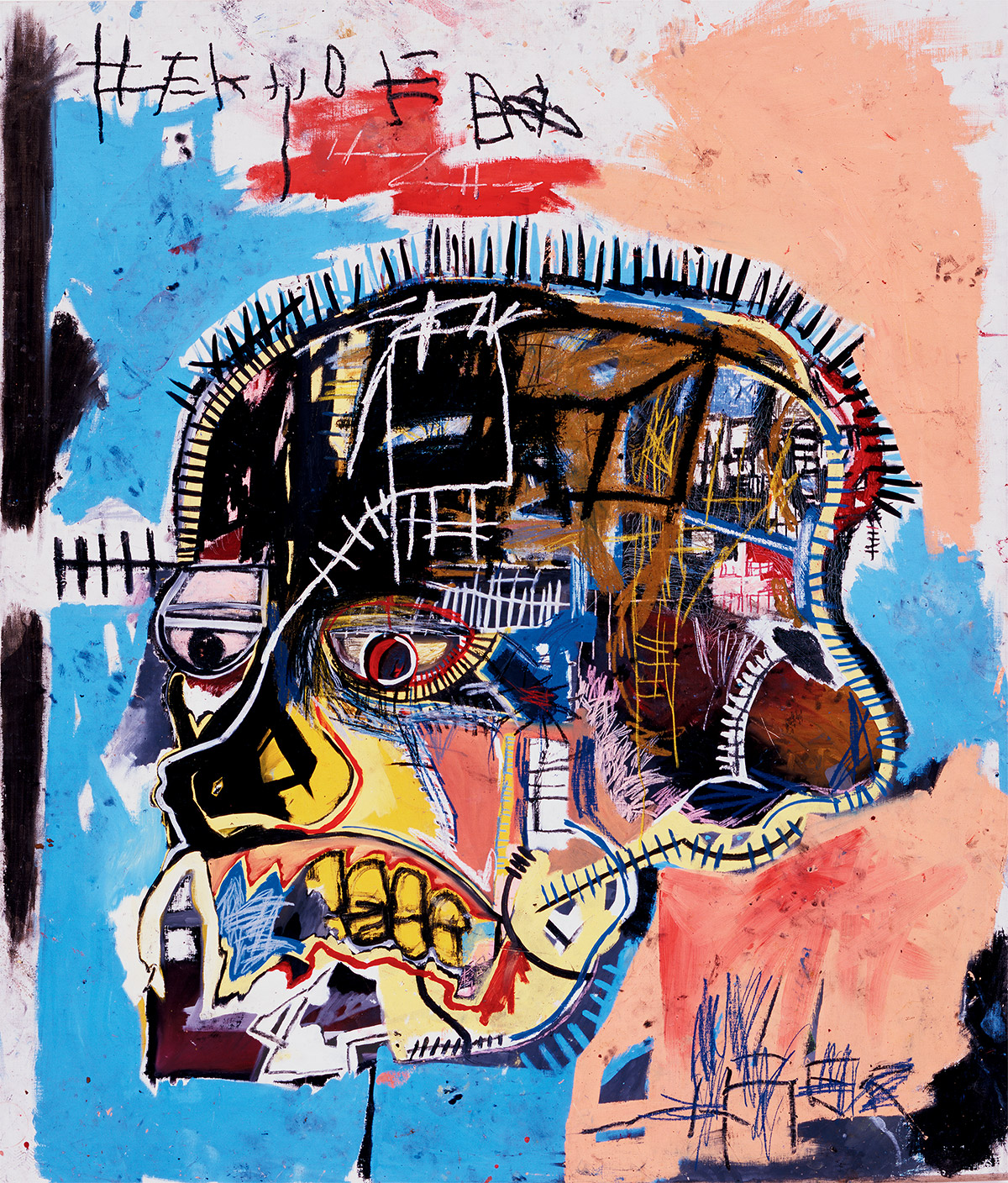

Untitled, 1981, by Jean-Michel Basquiat, acrylic and oilstick on canvas. Los Angeles. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

The Blind Woman, 1911, by Egon Schiele, gouache, white highlights and pencil on paper.

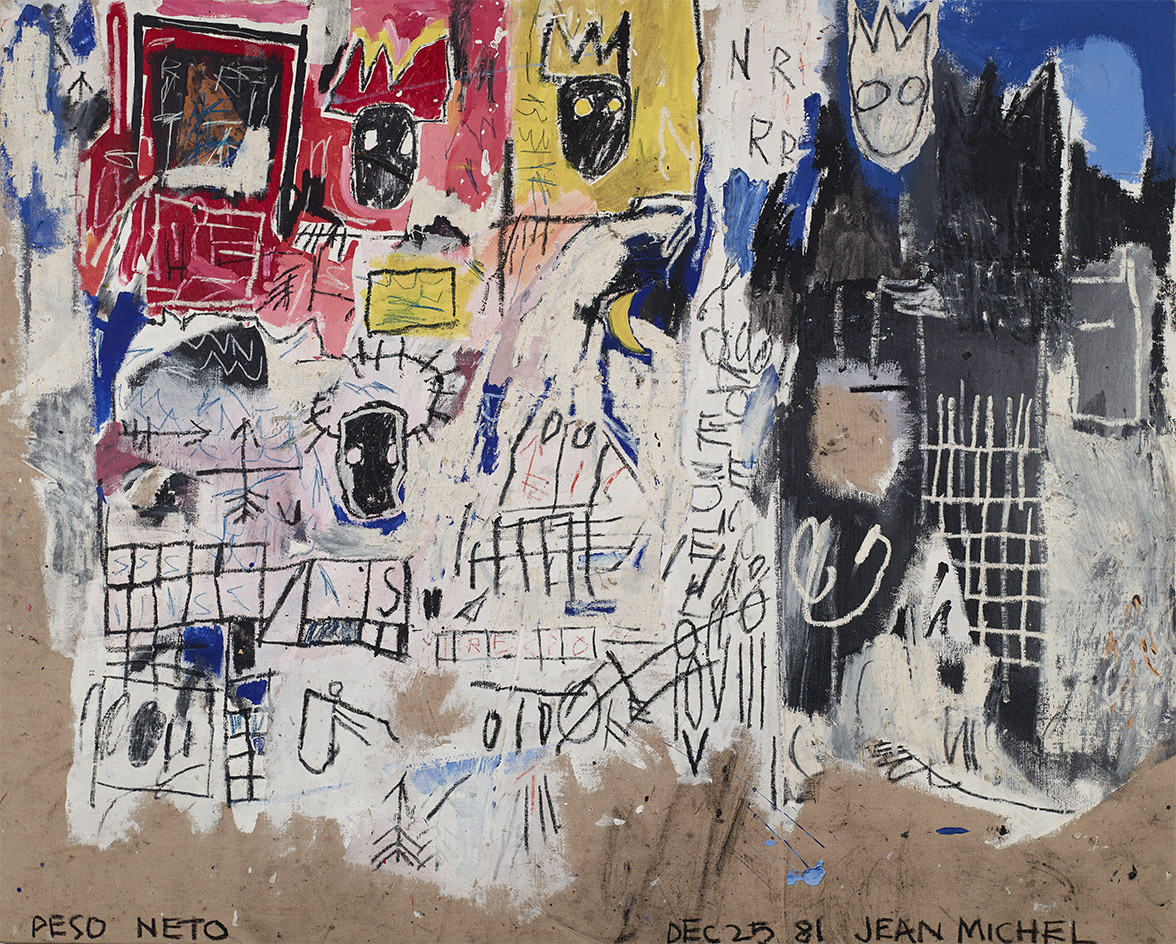

Crowns (Peso Neto), 1981, by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Photography: Marc Domage. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Installation view of ‘Jean-Michel Basquiat’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. © Fondation Louis Vuitton

INFORMATION

‘Jean-Michel Basquiat’ and ‘Egon Schiele’ are on view until 14 January 2019. For more information, visit the Fondation Louis Vuitton website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Fondation Louis Vuitton

8 Avenue du Mahatma Gandhi

75116 Paris