Immerse yourself in Helen Chadwick’s short and subversive career

Chadwick paved the way for the Young British Artists who followed her, challenging stereotypes and the accepted portrayal of the female body, as explored in a new retrospective at Hepworth Wakefield

Helen Chadwick’s work reverberates through contemporary art, though her practice lasted less than two decades. Creating expansive feminist work from the 1970s, the British artist utilised unconventional materials such as chocolate, flower petals, and bodily fluids in explorations of desire and decay. She died in 1996 at the age of 42, leaving a rich archive that forms The Hepworth Wakefield’s ‘Life Pleasures’, the first retrospective of the artist's work in over 20 years.

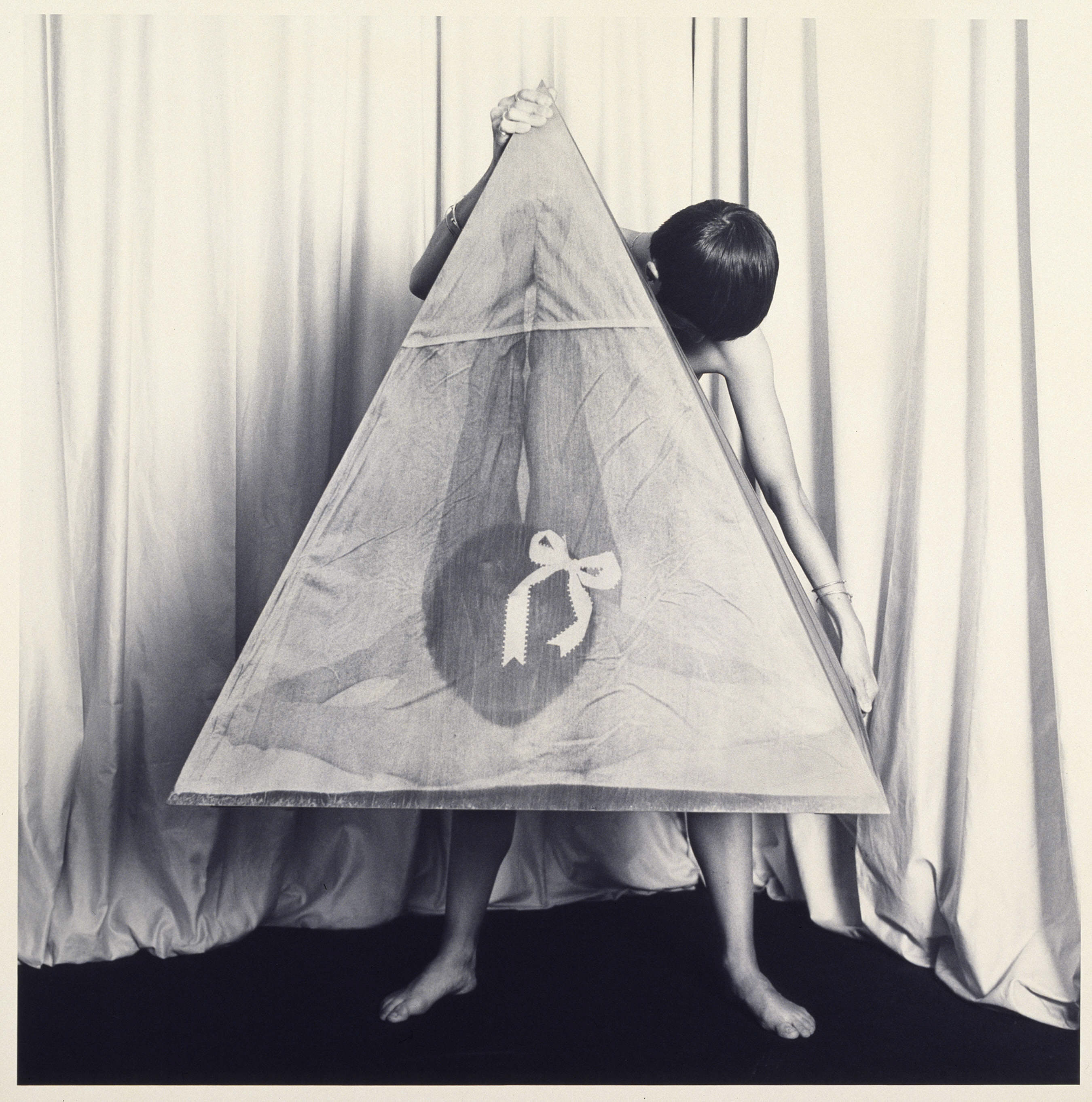

Helen Chadwick in collaboration with Mark Pilkington. The Labours V: Wigwam – 5 years, 1983-4

‘I wanted to look right back to 1976 and her Domestic Sanitation and Bargain Bed Bonanza costumes to demonstrate what an incredibly skilled maker she was,’ says curator Laura Smith, who has been working on the exhibition and adjacent Thames & Hudson book for over four years. ‘When I first visited the archive, I was expecting it to be punky, but it’s absolutely immaculate. Her handwriting is tiny and perfect. Everything is ordered and numbered. Her books look like a professional bound them. All the costumes’ hand-stitching is pin-perfect. The attention to detail and care blew my mind. I wanted to show that, alongside the feminism, humour, and joy.’

Meat, flowers, and berries regularly featured in Chadwick’s work. At The Hepworth Wakefield, her chocolate fountain, Cacao (1994), fills the space with a scent so overpowering it tips over into nauseating for many viewers. Smith notes that the piece requires a specific compressor to achieve the right kind of bubbling effect in the pool of chocolate. ‘Chadwick wanted it to look like a swamp, she didn’t want it to be pretty, it had to be ugly.’

Helen Chadwick, Piss Flowers, 1991-2. Installation at Frieze, 2013

The exhibition features some of Chadwick’s most ambitious works, including The Oval Court (1984–86), which has been conserved by the V&A and comprises 281 delicate photocopied pieces. The artist received a Turner Prize nomination in 1987 for the ICA exhibition that first housed this piece, which explores the transience of life through the artistic tradition of vanitas imagery. Her own nude body is shown 12 times, surrounded by items that would usually signify death in vanitas paintings, intended as a celebration of transience and ‘one-ness with all living things’.

In her lifetime, Chadwick was criticised – like many other feminist artists – for showing her own nude body. ‘She said she was exploring desire from the view of the object and the subject,’ says Smith. That didn’t stop reviewers from ‘saying she was encouraging rape and sexual violence’. Chadwick began her Viral Landscapes shortly after, which drew connections between the human body and nature, exploring possible parallels between ecological pollution and illness. ‘They’re incredibly beautiful and poignant,’ says Smith. ‘They speak to Chadwick’s anxieties around the AIDs crisis and the idea of human beings as a virus on the landscape.’

Helen Chadwick, Loop my Loop, 1991-2

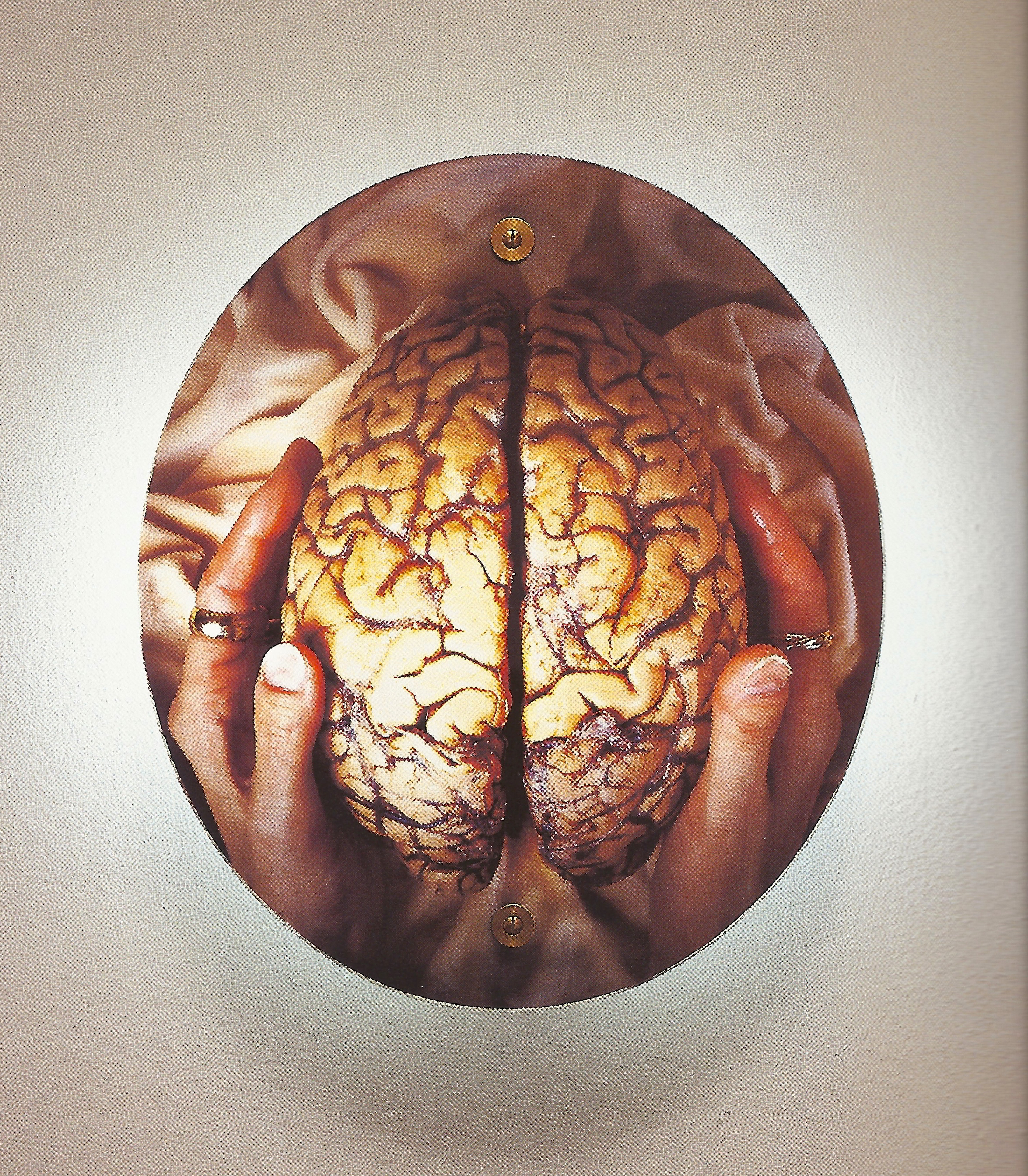

Chadwick addressed many subjects that were seen as deeply taboo. Her IVF series Unnatural Selection was undertaken at King's College Assisted Conception Unit in London. The images home in on embryos as a new form of still life, suspended in time until they are placed back into the body. While Chadwick didn’t look specifically for shock and sensation in her work, Smith notes that she did intend for her use of scent, powerful images, and unusual materials to stir a gut response. ‘I think she wanted people to have a bodily reaction, and through that be able to question constructs of beauty, desire, life, death, sex, gender. Rather than forcing us to think about it, she makes us physically react to it and examine our own instincts.’

Helen Chadwick with Piss Flowers from the exhibition ‘Helen Chadwick: Effluvia’, Serpentine Gallery, 1994

Chadwick famously taught at most art schools across London, with many YBAs as her students. Smith notes the influence she had on this iconic group, from Tracey Emin to Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst. ‘Andrew Cranston said she was the best teacher he ever had. She was really dedicated and didn’t try to bring her work to her students’ work. She would encourage students to be themselves and explore their freedom,’ says Smith. ‘I don’t think contemporary art in Britain would look the same today if it wasn’t for her. She caused a seismic shift in what artists felt able to do.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures’ is at Hepworth Wakefield until 27 October 2025, hepworthwakefield.org

Helen Chadwick, Self Portrait, 1991

Emily Steer is a London-based culture journalist and former editor of Elephant. She has written for titles including AnOther, BBC Culture, the Financial Times, and Frieze.