Why are we so obsessed with ghosts? From the psychological to the gothic, a new exhibition finds out

Ghosts have terrified us for centuries. ‘Ghosts: Visualizing the Supernatural’ at Kunstmuseum Basel asks what is going on

As a culture, we’ve always loved a good ghost. From a white sheet with black holes for eyes that haunts the pages of a children’s story book, to the Romantic and the Gothic, via spirit photography, ouija boards and Patrick Swayze, the attraction is undeniable. And why not? The question of where we go when we die, if anywhere, is knitted into the meaning of what it means to be human.

Das Medium Eva C. (aka Marthe Béraud) mit pantoffelähnlicher teleplastischer Form auf dem Kopf und einer Leuchterscheinung zwischen den Händen, Albert Freiherr von Schrenck-Notzing; Juliette Alexandre-Bisson, 17.05.1912

A new exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel is asking these questions, drawing on work created over the last 250 years for an eclectic and rich visual history. In the Western hemisphere, particularly, ghosts and the supernatural have become inextricably linked with psychology and science, and interpreted by artists, spun by political movements or become symbolic of trauma in an obsession that transcends mediums.

Why? ‘No matter if you believe they are real or not – they are fascinating,’ says Eva Reifert, curator of 19th-century and modern art at Kunstmuseum Basel. ‘They’ve changed with time, adapted to each moment, and they have always represented the shadowy aspects of our existence. Not of the light and not entirely of the darkness either, they are beings of the in-between. For the longest time, they were deeply serious – frightening and awe-inspiring, because they were so closely related to the dead and their continued presence, particularly if a debt had to be paid, or an act of violence had gone unpunished.’

Tell my mother not to worry (ii), Ryan Gander, 2012

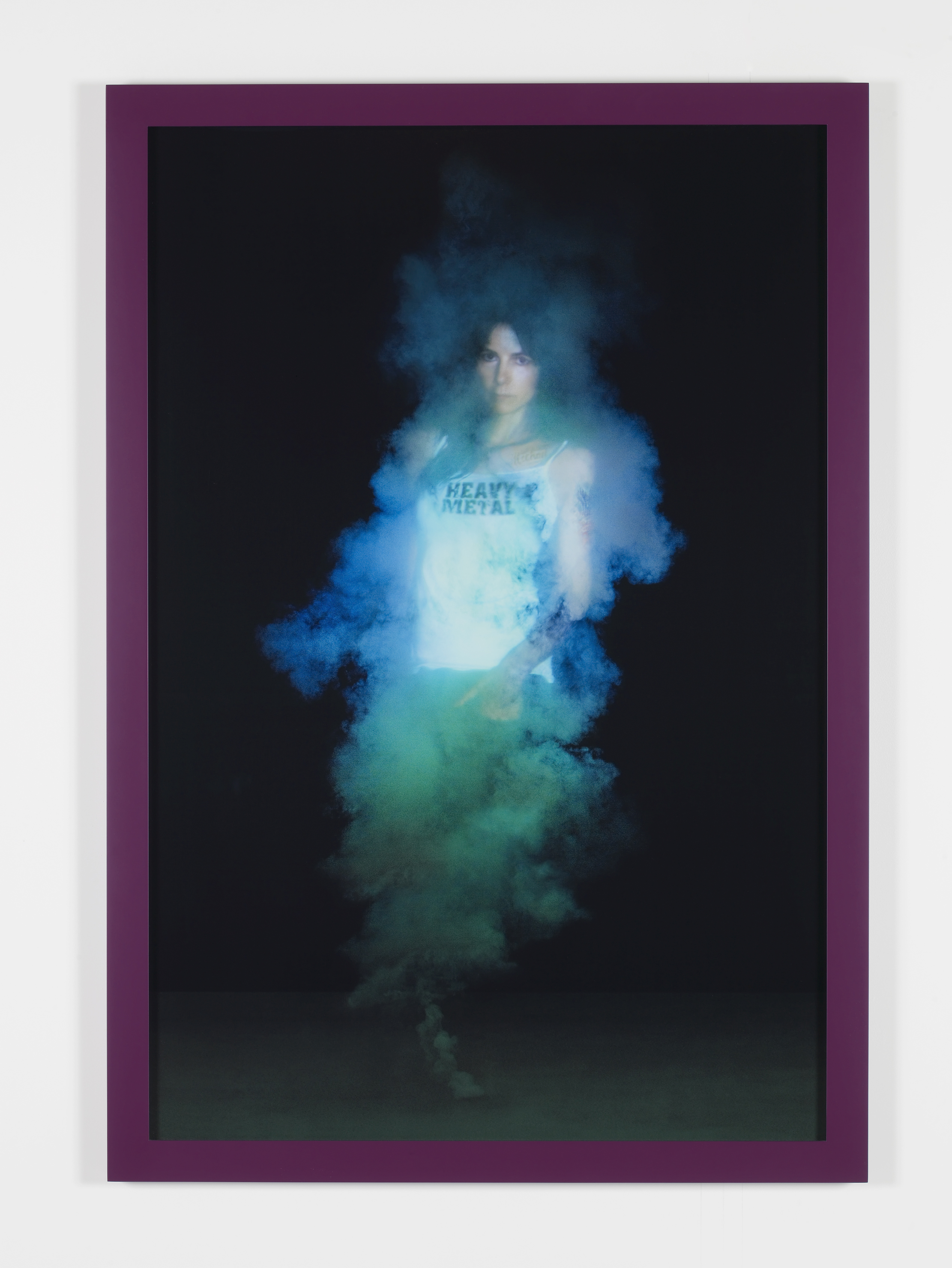

Me as a Ghost, Gillian Wearing, 2015

Since entering the popular mainstream a century ago, ghosts have ceased to be quite so serious, becoming more of a mirror held up to the whims and fluctuations of society. Whether comical, tongue-in-cheek or lightly anxious, they are useful vessels for our fears and the unpredictability of the future.

It wasn’t always the case, though. In the late 19th century, ghosts began to fascinate when considered alongside the new field of psychology, revealing the inner lives we usually keep hidden. When photography was invented in 1830, spirit photography revealed ghosts to be poignant wisps at the edge of a frame – later, we decided they looked like us.

‘As an art historian, I’m revelling in the enormous variety of iconographic elements that have been developed to indicate their unfathomable state as beings of the beyond or in-between,’ adds Reifert. ‘Clouds, smoke, stairs, the veil and sheets, translucency, flickering lights – artists, photographers, and filmmakers have played with and thus further established these visual clues conveying the transitory nature of ghosts. The most interesting form ghosts may take, however, is actually when they look like they did in life and it’s just the atmosphere around them that’s changing. The ghost of Hamlet’s father is such an example. Horatio describes him – and this is what is then shown in paintings and prints of the scene – as looking exactly like the deceased King Hamlet, dressed in full armor: “In the same figure like the king that's dead” (Horatio, Act I, Scene I).’

Ultimately, of course, ghosts tell us more about the living than the dead. ‘Ghosts chart the depth and width of human emotion, and sometimes the moral abyss into which individual people or even entire societies can fall.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

'Visualizing the Supernatural' at Kunstmuseum Basel from 20 September 2025 – 8 March 2026, kunstmuseumbasel.ch

All Of Us, Angela Deane, 2025

Spirit photograph, Staveley Bulford, 1921

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.