Reclaim the Earth, urge artists at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo

We discover the group exhibition ‘Reclaim the Earth’, a wake-up call for humans to reconsider our relationship with the planet (until 4 September 2022)

Aurélien Mole - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

‘Reclaim the Earth’ is both the title and the rallying cry of a new group exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. It looks beyond the Western model to other ways of existing in the world, where humans are an integral part of the environment rather than a dominating, and often destructive, force. ‘I am convinced that artists are like sentinels, warning us about the problems of society,’ says exhibition curator Daria de Beauvais.

The title comes from a collection of ecofeminist texts published in 1983. It is not a reference to militant feminism, De Beauvais explains, but rather ‘a term we find a lot in different struggles – to reclaim a territory, a sovereignty, an identity – and for different kinds of populations, notably Indigenous.’ Reclaiming the Earth means giving all life forms equal power to act.

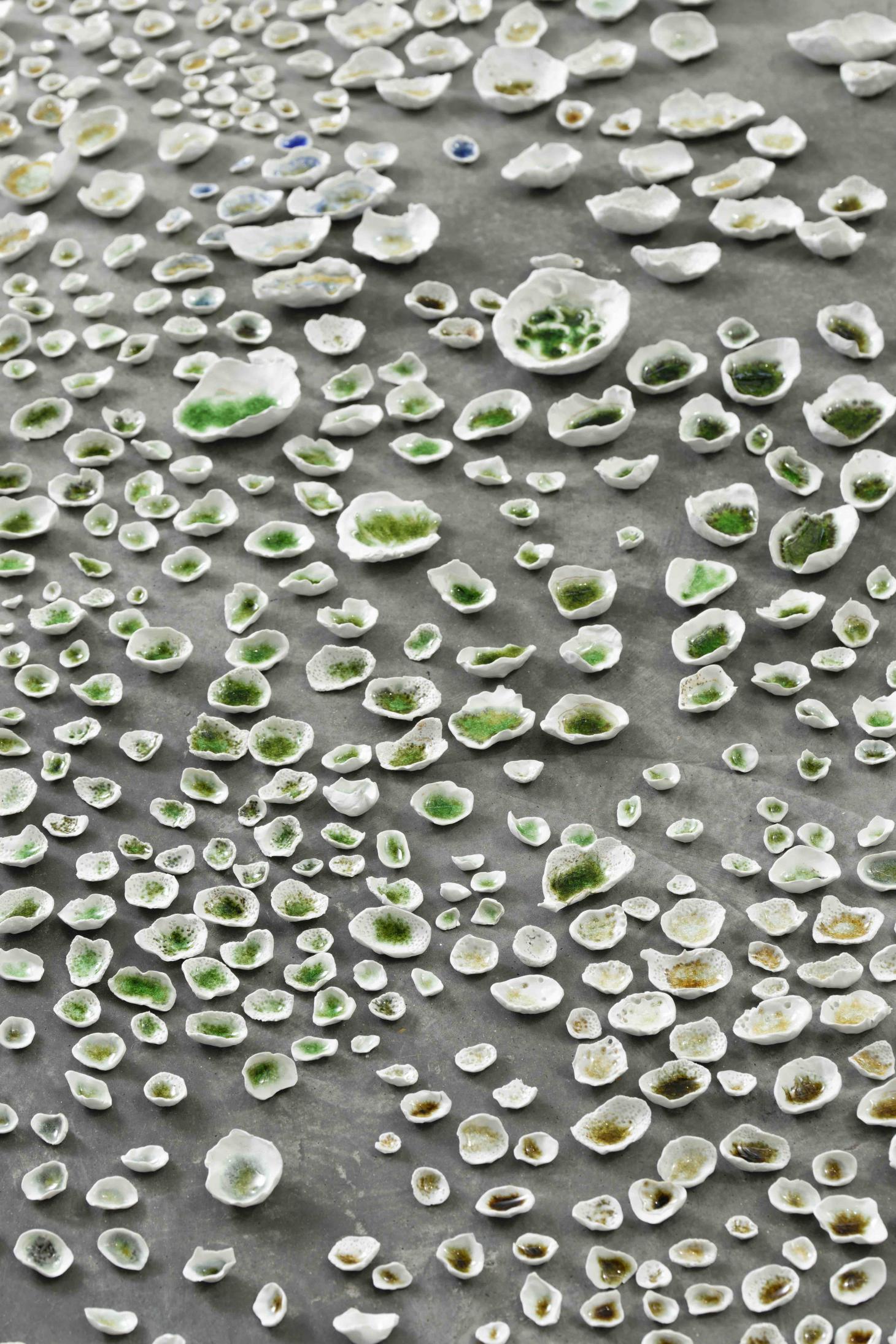

Kate Newby, it makes my day so much better if i speak to all of you., 2022. Porcelain, minerals, found glass (Paris). Produced at CRAFT (Limoges).

The show features 14 artists or collectives, half of them Indigenous. The Palais de Tokyo brought in two scientific advisors to ensure curatorial accuracy. In line with the museum’s own pledge to become more sustainable, 80 per cent of the scenography materials come from prior exhibitions.

‘Reclaim the Earth’ starts outside, in the urban environment, with two works by the New Zealand-born artist Kate Newby. Newby does all of her work in situ, using local materials and techniques, and is a careful observer of her surroundings, including the oft-overlooked details of the places she exhibits. Near an outdoor fountain, she replaced five neglected squares of earth with bricks imprinted with traces like ancestral marks and fossils. On the building itself, Newby removed five damaged glass panes from the 1930s front door, inserting stained glass panes into which she pressed parts of her body – a hand, an elbow, a knee – to create abstract motifs. (The door can only be seen when the museum is closed to the public.) ‘She notices things nobody else does, and showed me the building in another way,’ says De Beauvais.

Newby created one more work by asking the Palais de Tokyo team to pick up all the bits of glass they found on the streets of Paris, then melting the pieces into porcelain shells that she scattered on the floor like a bed of colourful oysters.

Top, Asinnajaq, Rock Piece (Ahuriri edition), 2018. Video, 4’2”. Above, Sebastián Calfuqueo, Kowkülen (Liquid Being), 2020. Video, 3’.

Two short videos bookend the exhibition, both of them showing artists literally blending into the landscape. One, by the Canadian Inuk artist Asinnajaq, portrays her emerging from a pile of rocks, a return to the land and a reference to funeral rites.

The other reveals Sebastián Calfuqueo, a Mapuche from Chile, in a ‘liquid state’, naked and half-submerged in a river.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Yhonnie Scarce, Shadow creeper, 2022. Blown glass yams, stainless steel, reinforced wire.

In Yhonnie Scarce’s Shadow creeper, a shower of blown glass pieces rains down from the ceiling. Their form was inspired by yams, which are important to the cuisine of Aboriginal Australians. Though beautiful, the glass cloud is meant to evoke the effects of the nuclear tests the British carried out in the Australian desert between 1956 and 1963, crystallising the sand and leaving radiation that persists to this day.

Megan Cope, a Quandamooka from Australia, has been directly affected by climate change, her studio destroyed by the recent floods in her country. She created her installation Untitled (Death Song) (pictured top) prior to the event, in 2020. It assembles the tools and debris of mining and drilling: soil augers, oil drums, rocks. The accompanying soundtrack evokes the particular wailing cry of an endangered Australian bird, the bush stone-curlew.

Solange Pessoa, Cathedral, 1990-2003. Hair, leather, fabric. Video, 7’. Rubell Family Collection (Miami).

Animism is a recurrent theme of the show, such as in the installation Catedral, by Brazil’s Solange Pessoa.

She took human hair, used as an offering in pagan rites, and attached it to a backing several metres long, rolled onto spools like a long, skinny carpet. Unfurled in the space, it snakes across the floor and up the wall as though alive.

Huma Bhabha, (from left) Receiver, 2019. Painted bronze. The Past is a Foreign Country, 2019. Wood, cork, Styrofoam, acrylic, oil stick, wire, white-tailed deer skull, tire tread. God Of Some Things, 2011. Patinated bronze

Huma Bhabha’s three totemic figures guard the entrance to a small room showing a film by the Karrabing Film Collective, founded by a group of Aboriginal Australians and the American anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli.

With a substance rubbed onto her skin to make it extra-white, Povinelli assumes the role of the monster in The Family and the Zombie, a satirical tale about Indigenous children playing in a natural setting that is increasingly corrupted by objects of consumption.

Karrabing Film Collective, The Family and the Zombie, 2021. Video, 29’23”.

In Study for a Monument, a sort of war memorial, the Iranian-born artist Abbas Akhavan’s fragmented bronze plants lay on white sheets on the floor, like remnants of weapons, or corpses waiting to be identified.

The plants are endangered or extinct species from the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, an area that has repeatedly been subject to conflict and ecological disturbance

Foreground, Abbas Akhavan, Study for a Monument, 2013-2014. Cast bronze, white cotton sheets. Art Jameel Collection (Dubai). Family Servais Collection (Brussels). Courtesy of the artist, Catriona Jeffries (Vancouver) & The Third Line (Dubai). Background, Thu-Van Tran, De Vert à Orange – Espèces Exotiques Envahissantes –, 2022. Photographic prints on Fuji paper, laminated and framed, alcohol, dye. Courtesy of the artist & Almine Rech (Paris)

To either side of this work are two others in which plants take the upper hand. The rebellion of the roots is a series of naïve drawings by Peru’s Daniela Ortiz showing, for example, coconuts falling on the head of Belgium’s interior minister.

Facing it, the Vietnamese artist Thu-Van Tran created a botanical panorama in fiery colours, superimposing photos of tropical plants in European greenhouses over images of rubber trees in the Amazon, a comment on how human intervention and colonisation can lead to mutations and invasive species. The implication is clear: if we don’t reclaim the Earth, the Earth might just reclaim us.

Daniela Ortiz, The Rebellion of the Roots, 2020 – ongoing. Acrylic on wood.

Amabaka x Olaniyi Studio, Nono: Soil Temple, 2022. Soil, metal, stainless steel ropes, fabric (organic cotton, recycled ocean plastic fibre, seaweed fibre).

D Harding, INTERNATIONAL ROCK ART RED, 2022. Wool felt made with Jan Oliver, red ochre, gum arabicum, hematite.

INFORMATION

‘Reclaim the Earth’ runs until 4 September 2022 at Palais de Tokyo, 13 Avenue du Président Wilson, Paris 16e

The exhibition is a collaboration with the Embassy of Australia in France, the Embassy of France in Australia, the Canadian Cultural Centre (Paris), the Ecole normale supérieure (Paris), E-WERK (Luckenwalde), Fondation Opale (Lens, Switzerland), Ikon Gallery (Birmingham), Laboratoire Espace Cerveau (IAC, Villeurbanne), Madre (Naples), and the Serpentine Galleries (London)

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.