Taiwan’s new ‘museumbrary’ is a paradigm-shifting, cube-shaped cultural hub

Part museum, part library, the SANAA-designed Taichung Green Museumbrary contains a world of sweeping curves and flowing possibilities, immersed in a natural setting

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

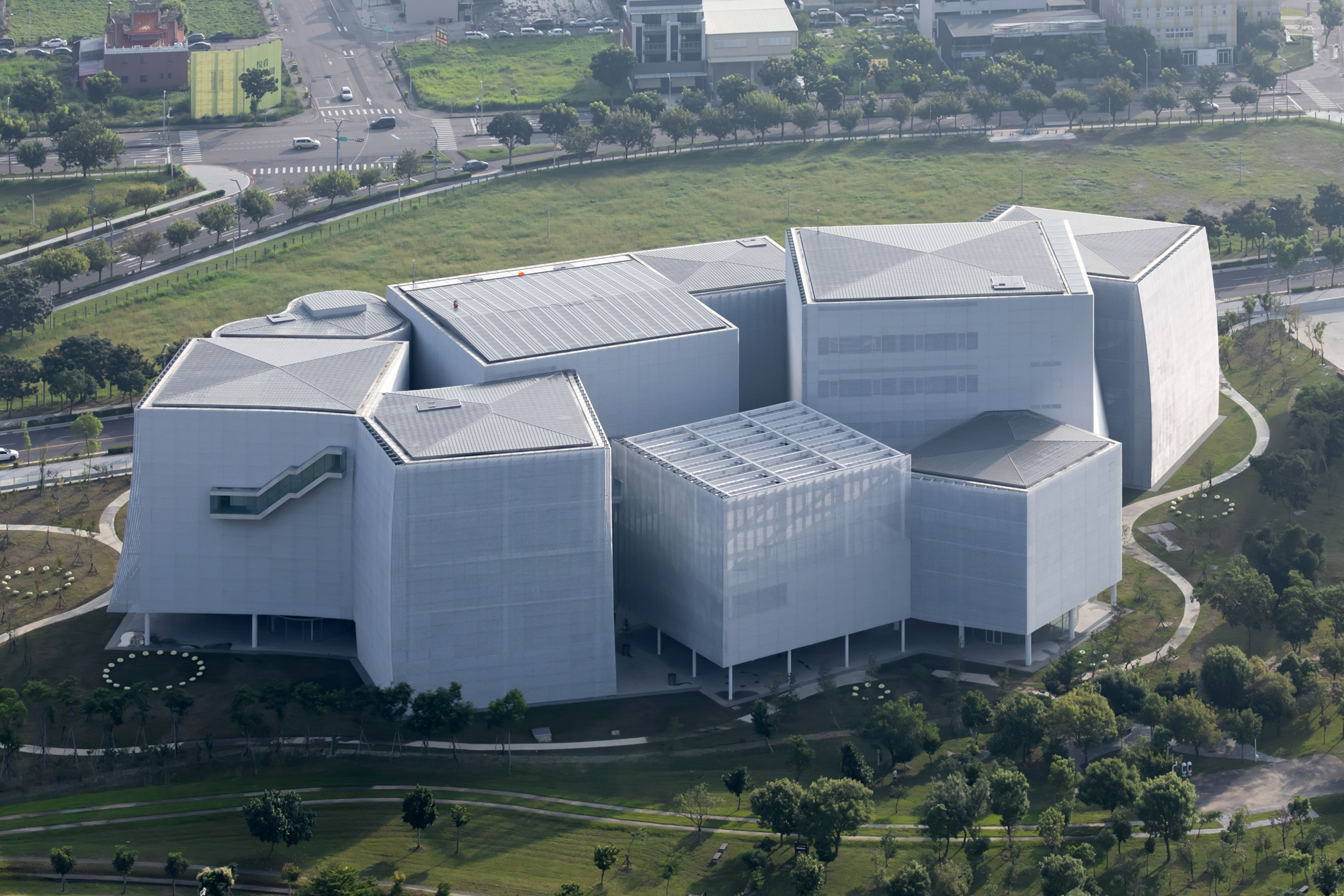

Transparent, fluid, light, fragmented, connected: a tumbling flow of eight vast cubical volumes appears to hover above a green park, sunlight and wind filtering freely through mesh façades. However, perhaps even more remarkable than this new structure’s monumental scale, weightless presence and abstraction of form is its function: it’s an art museum – and it’s also a library.

The idea of mixing two established institutions to create a paradigm-shifting new cultural concept lies at the heart of Taichung Green Museumbrary in Taiwan, designed by Japanese architects SANAA. A spatial dialogue connecting books and art, the hybrid ‘museumbrary’, which opens in December 2025, dissolves conventional boundaries and softly integrates Taichung Art Museum with Taichung Public Library.

Tour the new Taichung Green Museumbrary

SANAA’s largest cultural project to date, it spans eight cubed volumes gently raised off the ground, all interconnected in unexpected ways, creating a spatial harmony of circles, lines, curves, corners, spirals, pathways, voids and shaded plazas. Home to five art galleries, airy expanses of library floors and layered reading zones, plus more than a million physical and digital book resources, the lightly fragmented architectural form dissolves the edges between inside and out, architecture and nature, museum and library.

For SANAA’s founders Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, the 12-year-long project is anchored in the idea of creating a transformative cultural complex immersed in its natural setting. Speaking to us on site ahead of the opening, Sejima explains: ‘People can encounter new art and new books and have two different kinds of information, new experiences, new learning. These two programmes stand independently, softly – but at the same time, there are many possibilities to meet and mix them both.’

Nishizawa adds, ‘When I was a kid, when I went to the library to select a book, there was no space. Then, when I went to a museum, I saw real things, but there was no knowledge behind them. But what if a library has space and a museum also allowed kids to learn? We thought it would be nice to have a museum and a library; we always try to explore new functions that respond to our time. A museum can become a school; a café and a restaurant can be together; part of a supermarket can become a community centre. This is our way of thinking. A continuation from the past – but there must be something new.’

Approaching Taichung Green Museumbrary, a sense of transparency is immediately evoked by the volumes’ dual-layer façades, with inner glass and metal cladding wrapped in a connective flow of aluminium expanded metal mesh, filtering sun and wind. Explaining how the concept evolved from soft spheres to cubes, Nishizawa says, ‘Some are big. Some are small. Inside, there is freedom. People can explore. There is mutual interaction between boxes.’

The structures are linked by multiple access routes and shaded concrete plazas that gently undulate like rolling hills, dissolving the threshold with its setting in the 67-hectare Central Park. ‘We wanted to open up and make a space that builds a relationship with the park,’ says Sejima. ‘It’s a very public space, which is defined by how it will be used by everyone.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Inside, a jigsaw of steel curves, internal windows, coiled walkways and clean-lined bridges shifts into focus. The main lobby is a light-flooded space with a low circular pond, temple-like stones at its base, while the art museum’s 27m-high entrance (Taiwan’s tallest art exhibition space) is anchored by a spiralling slope leading to five galleries, in the middle of which cascades a light-filtering artwork by South Korean artist Haegue Yang. Galleries vary in size and texture – one has soaring 9m-high ceilings and a polished concrete floor; another has a lantern-like ceiling wrapped in fibreglass fabric, softly diffusing both natural and artificial light.

The hybrid cultural concept aims to be a catalyst for curatorial innovation, as reflected in its inaugural show, ‘A Call of All Beings: See you tomorrow, same time, same place’ (from 13 December 2025 – 12 April 2026). Site-reactive works include Belgian artist Adrien Tirtiaux’s disruptive vertical intervention, which cuts through two layers of galleries. Library spaces are no less connective: cloud-like ceiling panels, Arne Jacobsen chairs and, at the seventh-floor apex, low-lying bookshelves to maximise the sweeping views.

The Culture Forest roof garden is another highlight, with a circular concrete pathway wrapped in glass flowing around pots of sweet osmanthus, surrounded by park and city, skies visible through mesh. There are hints of Taiwan throughout the design, a collaboration with Taipei-based Ricky Liu & Associates. This can be seen in the presence of its expansive shading areas on the ground floor, providing respite from the sun, an architectural hallmark in Taiwan.

Transparency, flow and freedom are defining qualities that ultimately connect both books and art. As Nishizawa says, ‘In Japan, transparency and movement are very important. We have religion, we have nature. There is no one centre. Nature is really dynamic: we have typhoons, earthquakes, tsunamis – there is always something happening. We have a feeling that we’re living together with nature, and we’re always moving. Nothing stays the same.’

Highlighting how this shapes the space, he says, ‘Curves mean a continuation. There is a diversity of circulation and connections inside, to allow people to walk from one pavilion to another. Each space has a feeling of freedom.’ For Taichung Museum of Art director Yi-Hsin Nicole Lai, this sense of freedom permeates the project: ‘Through the spirit of openness and integration, the museum seeks to inspire new ways of seeing and thinking, build connections between people and the city, art and nature – and become a place that sparks dialogue and reflection.’

And ultimately, it all comes back to the park – and the dynamic between humans, architecture and nature. ‘A park doesn’t define its aim or function – everyone can react or find their own way to spend their time and enjoy themselves,’ says Sejima. ‘But at the same time, you can always feel the presence of people and make space together, naturally. This is, for me, very important. I want to make architecture like this kind of space.’

Danielle Demetriou is a British writer and editor who moved from London to Japan in 2007. She writes about design, architecture and culture (for newspapers, magazines and books) and lives in an old machiya townhouse in Kyoto.

Instagram - @danielleinjapan